- •Contents

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •About the Authors

- •How to Use Herbal Medicines

- •Introduction

- •General References

- •Agnus Castus

- •Agrimony

- •Alfalfa

- •Aloe Vera

- •Aloes

- •Angelica

- •Aniseed

- •Apricot

- •Arnica

- •Artichoke

- •Asafoetida

- •Avens

- •Bayberry

- •Bilberry

- •Bloodroot

- •Blue Flag

- •Bogbean

- •Boldo

- •Boneset

- •Borage

- •Broom

- •Buchu

- •Burdock

- •Burnet

- •Butterbur

- •Calamus

- •Calendula

- •Capsicum

- •Cascara

- •Cassia

- •Cat’s Claw

- •Celandine, Greater

- •Celery

- •Centaury

- •Cereus

- •Chamomile, German

- •Chamomile, Roman

- •Chaparral

- •Cinnamon

- •Clivers

- •Clove

- •Cohosh, Black

- •Cohosh, Blue

- •Cola

- •Coltsfoot

- •Comfrey

- •Corn Silk

- •Couchgrass

- •Cowslip

- •Cranberry

- •Damiana

- •Dandelion

- •Devil’s Claw

- •Drosera

- •Echinacea

- •Elder

- •Elecampane

- •Ephedra

- •Eucalyptus

- •Euphorbia

- •Evening Primrose

- •Eyebright

- •False Unicorn

- •Fenugreek

- •Feverfew

- •Figwort

- •Frangula

- •Fucus

- •Fumitory

- •Garlic

- •Gentian

- •Ginger

- •Ginkgo

- •Ginseng, Eleutherococcus

- •Ginseng, Panax

- •Golden Seal

- •Gravel Root

- •Ground Ivy

- •Guaiacum

- •Hawthorn

- •Holy Thistle

- •Hops

- •Horehound, Black

- •Horehound, White

- •Horse-chestnut

- •Horseradish

- •Hydrangea

- •Hydrocotyle

- •Ispaghula

- •Jamaica Dogwood

- •Java Tea

- •Juniper

- •Kava

- •Lady’s Slipper

- •Lemon Verbena

- •Liferoot

- •Lime Flower

- •Liquorice

- •Lobelia

- •Marshmallow

- •Meadowsweet

- •Melissa

- •Milk Thistle

- •Mistletoe

- •Motherwort

- •Myrrh

- •Nettle

- •Parsley

- •Parsley Piert

- •Passionflower

- •Pennyroyal

- •Pilewort

- •Plantain

- •Pleurisy Root

- •Pokeroot

- •Poplar

- •Prickly Ash, Northern

- •Prickly Ash, Southern

- •Pulsatilla

- •Quassia

- •Queen’s Delight

- •Raspberry

- •Red Clover

- •Rhodiola

- •Rhubarb

- •Rosemary

- •Sage

- •Sarsaparilla

- •Sassafras

- •Saw Palmetto

- •Scullcap

- •Senega

- •Senna

- •Shepherd’s Purse

- •Skunk Cabbage

- •Slippery Elm

- •Squill

- •St John’s Wort

- •Stone Root

- •Tansy

- •Thyme

- •Uva-Ursi

- •Valerian

- •Vervain

- •Wild Carrot

- •Wild Lettuce

- •Willow

- •Witch Hazel

- •Yarrow

- •Yellow Dock

- •Yucca

- •1 Potential Drug–Herb Interactions

- •4 Preparations Directory

- •5 Suppliers Directory

- •Index

Meadowsweet

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

The chemistry of meadowsweet is characterised by a number of phenolic constituents, including flavonoids, salicylates and tannins. Documented scientific evidence from preclinical studies supports some of the antiseptic, antirheumatic and astringent traditional uses. However, there is a lack of clinical research assessing the efficacy and safety of meadowsweet. No documented toxicity data were located for meadowsweet and, in view of this, excessive use of meadowsweet and use during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Species (Family)

Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. (Rosaceae)

Synonym(s)

Dropwort, Filipendula, Queen of the Meadow

Part(s) Used

Herb

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHC 1992(G6)

BHP 1996(G9)

BP 2007(G84)

Complete German Commission E(G3)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

Ph Eur 2007(G81)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL(G37)

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General References G2 and G6.

Flavonoids Flavonols, flavones, flavanones and chalcone deriva-

tives (e.g. hyperoside(1) and spireoside,(2) kaempferol glucoside(3) and avicularin.(4)

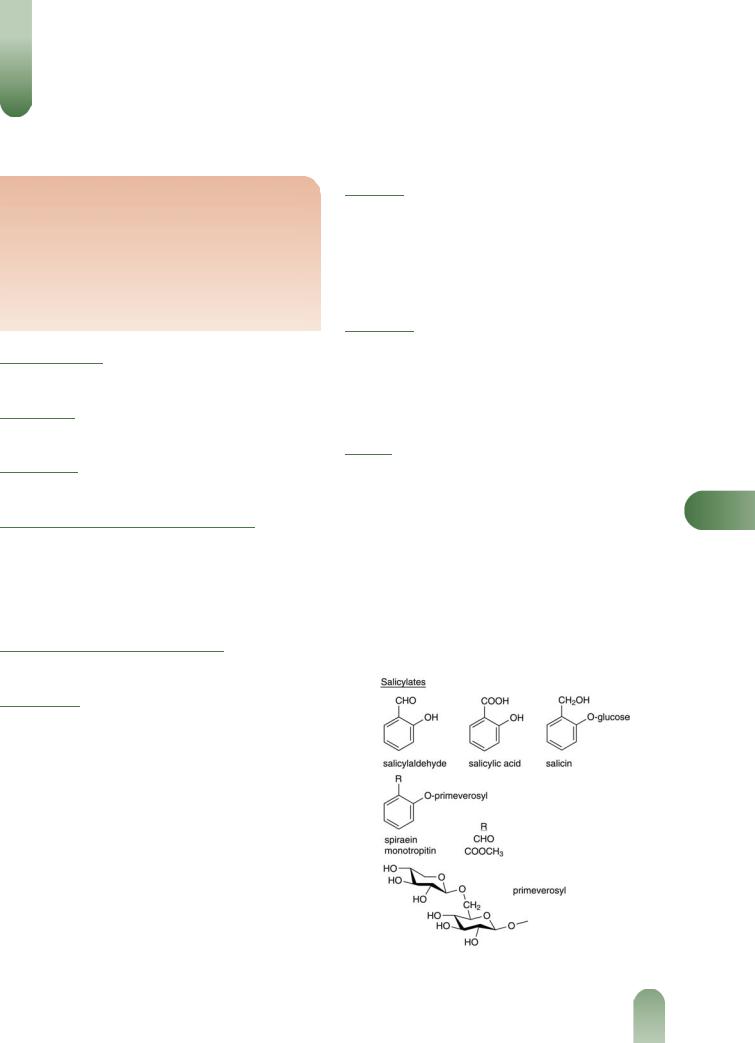

Salicylates Main components of the volatile oil including salicylaldehyde (major, up to 70%), gaultherin, isosalicin, methyl salicylate, monotropitin, salicin, salicylic acid and spirein.(5–8)

Tannins 1% (alcoholic extract), 12.5% (aqueous extract).(5) Hydrolysable type;(9) leaf extracts have also yielded catechols,(1) compounds normally associated with condensed tannins.

Volatile oils Many phenolic components including salicylates (see above), benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, ethyl benzoate, heliotropin, phenylacetate, vanillin.(4, 5)

Other constituents Coumarin (trace),(1) mucilage, carbohydrates and ascorbic acid (vitamin C).

Food Use

Meadowsweet is listed by the Council of Europe as a natural source of food flavouring (category N2). This category indicates that meadowsweet can be added to foodstuffs in small quantities, with a possible limitation of an active principle (as yet unspecified) in the final product.(G16) Previously, meadowsweet

has been listed by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) as a Herb of Undefined Safety.(G22)

Herbal Use

Meadowsweet is stated to possess stomachic, mild urinary antiseptic, antirheumatic, astringent and antacid properties. Traditionally, it has been used for atonic dyspepsia with heartburn and hyperacidity, acute catarrhal cystitis, rheumatic muscle and joint pains, diarrhoea in children, and specifically for the prophylaxis and treatment of peptic ulcer.(G2, G6, G7, G8, G64)

Dosage

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses recommended in standard herbal reference texts are given below.

Dried herb 4–6 g as an infusion three times daily.(G6, G7)

Liquid extract 1.5–6.0 mL (1 : 1 in 25% alcohol) three times |

M |

|

daily.(G6, G7) |

|

|

Tincture 2–4 mL (1 : 5 in 45% alcohol) three times daily.(G6, G7) |

|

|

Pharmacological Actions |

|

|

|

|

|

In vitro and animal studies |

|

|

Lowering of motor activity and rectal temperature, myorelaxation |

|

|

and potentiation of narcotic action have been documented for |

|

|

meadowsweet.(5) In addition, flower extracts have been reported to |

|

|

Figure 1 Selected constituents of meadowsweet.

423

424 Meadowsweet

Figure 2 Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria).

prolong life expectancy of mice, lower vascular permeability and prevent the development of stomach ulcers in rats and mice.(5, 10, 11) However, meadowsweet has also been reported to potentiate the ulcerogenic properties of histamine in the guinea-pig.(10) The anti-ulcer action documented for meadowsweet is associated with the aqueous extract and greatest activity has been observed with the flowers.(9, 11) Meadowsweet has been reported to increase bronchial tone in the cat(9) and to potentiate the bronchospastic properties of histamine in the guinea-pig.(9) In vitro, meadows-

weet has been reported to increase intestinal tone in the guineapig and uterine tone in the rabbit.(9)

Bacteriostatic activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris and

MPseudomonas aeruginosa has been documented for flower extracts.(12)

Tannins are generally considered to possess astringent proper-

ties and have been reported as constituents of meadowsweet. Meadowsweet is stated to promote uric acid excretion.(G42)

Clinical studies

There is a lack of clinical research assessing the effects of meadowsweet and rigorous randomised controlled clinical trials are required.

Side-effects, Toxicity

None documented. However, there is a lack of clinical safety and toxicity data for meadowsweet and further investigation of these aspects is required.

Figure 3 Meadowsweet – dried drug substance (herb).

Contra-indications, Warnings

Salicylate constituents have been documented and therefore the usual precautions recommended for salicylates are relevant for meadowsweet (see Willow). Meadowsweet is stated to be used for the treatment of diarrhoea in children, but in view of the salicylate constituents, this is not advisable.

Bronchospastic activity has been documented in preclinical studies and, therefore, it is prudent to advise that meadowsweet should be used with caution by asthmatics.

Aqueous extracts have been reported to contain high tannin concentrations and excessive consumption should therefore be avoided.

Drug interactions None documented. However, the potential for preparations of meadowsweet to interact with other medicines administered concurrently, particularly those with similar or opposing effects, should be considered.

Pregnancy and lactation In vitro utero-activity has been documented for meadowsweet. In view of the salicylate constituents and the lack of toxicity data, the use of meadowsweet during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Preparations

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations

Czech Republic: Antirevmaticky Caj. France: Mediflor Tisane Antirhumatismale No 2; Mediflor Tisane No 4 Diuretique; Polypirine. Italy: Pik Gel. Spain: Dolosul; Natusor Harpagosinol; Natusor Renal. Switzerland: Urinex. UK: Acidosis; Acidosis; Indigestion Mixture; Napiers Uva Ursi Tea; Roberts Acidosis Tablets. USA: Amerigel.

References

1 Genic AY, Ladnaya LY. Phytochemical study of Filipendula ulmaria Maxim. and Filipendula hexapetala Gilib. of flora of the Lvov region.

Farm Zh (Kiev) 1980; 1: 50–52.

2Novikova NN. Use of Filipendula ulmaria in medicine. Tr Perm Farm Inst 1969; 267–270.

3Scheer T, Wichtl M. Zum Vorkommen von Kämpferol-40-O-b-D- glucopyranoside in Filipendula ulmaria und Allium cepa. Planta Med

1987 53: 573–574.

4Syuzeva ZF, Novikova NN. Flavonoid composition of Filipendula ulmaria queen-of-the meadow. Nauch Tr Perm Farm Inst 1973; 5: 2– 26.

5Barnaulov OD et al. Chemical composition and primary evaluation of the properties of preparations from Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim

flowers. Rastit Resur 1977; 13: 661–669.

6Saifullina NA, Kozhina IS. Composition of essential oils from flowers of Filipendula ulmaria, F. denudata, and F. stepposa. Rastit Resur

1975; 11: 542–544.

7 Thieme H. Isolierung eines neuen phenolischen glykosids aus den blüten von Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. Pharmazie 1966; 21: 123.

8Valle MG et al. Das ätherische öl aus Filipendula ulmaria. Planta Med

1988; 54: 181–182.

9Barnaulov OD et al. Preliminary evaluation of the spasmolytic properties of some natural compounds and galenic preparations.

Rastit Resur 1978; 14: 573–579.

10Barnaulov OD, Denisenko PP. Antiulcerogenic action of the decoction from flowers of Filipendula ulmaria (L.). Pharmakol-Toxicol (Moscow) 1980; 43: 700–705.

11Yanutsh AY et al. A study of the antiulcerative action of the extracts from the supernatant part and roots of Filipendula ulmaria. Farm Zh (Kiev) 1982; 37: 53–56.

12Catanicin-Hintz I et al. Action of some plant extracts on the bacteria involved in urinary infections. Clujul-Med 1983; 56: 381–384.

Melissa

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

Randomised clinical trials have suggested that topical lemon balm extract may have some effects on healing cutaneous lesions resulting from HSV-1 virus infection, although further rigorous studies are required to determine whether there is any effect on recurrence of infection. There is some evidence from randomised controlled trials of combination preparations containing lemon balm leaf extract to support the efficacy of such products in individuals with minor sleep disorders, there has been little investigation of the effects of lemon balm extract alone on sleep quality. Further studies are required to determine the effects of preparations of lemon balm leaf extract in individuals with sleep disorders. Supporting evidence for the use of lemon balm for gastrointestinal complaints is limited to in vitro work and requires clinical investigation.

Small-scale, short-term studies indicate that oral combination preparations containing lemon balm extract and topical preparations of lemon balm extract are well tolerated. However, there is a lack of research investigating the safety of long-term administration of lemon balm. In view of the lack of toxicity data, oral administration of lemon balm during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Species (Family)

Melissa officinalis L. (Labiatae/Lamiaceae)

Synonym(s)

Balm, Faucibarba officinalis (L.) Dulac, Honeyplant, Lemon Balm, Mutelia officinalis (L.) Gren. ex Mutel, Sweet Balm,

Thymus melissa Krause

Part(s) Used

Dried leaves and flowering tops

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHP 1996(G9)

BP 2007 (Lemon Balm)(G84)

Complete German Commission E (Lemon Balm)(G3) ESCOP 2003(G76)

Martindale 35th edition(G85) Ph Eur 2007(G81)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL(G37)

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General References G2 and G52.

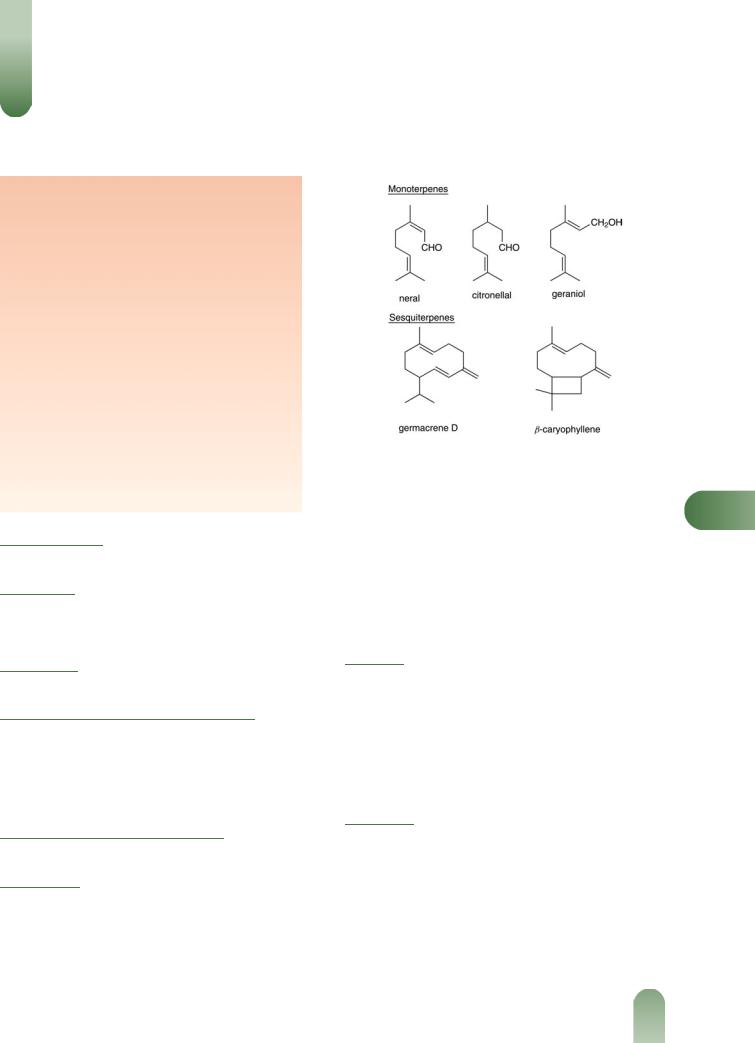

Volatile oil 0.06–0.375% v/m.(1, G52) Contains at least 70 components,(G2) including: monoterpenes >60%. Mainly aldehydes, including citronellal, geranial, neral; also citronellol,

Figure 1 Selected constituents of melissa.

geraniol, nerol, b-ocimene.(2, 3) |

Sesquiterpenes >35%. b-Caryo- |

M |

phyllene, germacrene D. |

|

Flavonoids 0.5%. Including glycosides of luteolin (e.g. luteolin 30-O-b-D-glucuronide),(4) quercetin, apigenin and kaempferol.

Polyphenols Protocatechuic acid, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives,(2) caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, rosmarinic acid,(2) 2-(30,40- dihydroxyphenyl)-1,3-benzodioxole-5-aldehyde.(5)

Food Use

Lemon balm is used to give fragrance to wine, tea and beer. Lemon balm (herb, flowers, flower tips) is listed by the Council of Europe as a natural source of food flavouring (category N2). This category indicates that lemon balm can be added to foodstuffs in

small quantities, with a possible limitation of an active principle (as yet unspecified) in the final product.(G16) Previously, lemon

balm has been listed as GRAS (Generally Recognised As Safe).(G65)

Herbal Use

Lemon balm has been used traditionally for its sedative,

spasmolytic and antibacterial properties.(G54) It is also stated to be a carminative, diaphoretic and a febrifuge,(G64) and has been

used for headaches, gastrointestinal disorders, nervousness and rheumatism.(5) Current interest is focused on its use as a sedative, and topically in herpes simplex labialis as a result of infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). The German Commission E monographs state that lemon balm can be used for nervous sleeping disorders and functional gastrointestinal complaints.(G4)

425

426 Melissa

Figure 2 Melissa (Melissa officinalis).

Dosage

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses recommended in standard herbal reference texts are given below.

MDried herb 1.5–4.5 g as an infusion in 150 mL water several times daily.(G4)

Topical application Cream containing 1% of a lyophilised

aqueous extract of dried leaves of Melissa officinalis (70 : 1) two to four times daily.(G52)

Pharmacological Actions

In vitro and animal studies

Antiviral activity Aqueous extracts of Melissa officinalis have been reported to inhibit the development of several viruses.(6– 8, G52) The virucidal effect of several aqueous extracts of M. officinalis against HSV-1 has been demonstrated in a rabbit kidney cell line.(9) However, the extracts appeared to have no activity against experimental HSV-1 infection in the eyes of rabbits.(9)

Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) activity has been reported for an aqueous extract of M. officinalis in in vitro studies using MT-4 cells; the ED50 (50% effective dose for inhibition of HIV-1-induced cytopathogenicity) was found to be 16 mg/mL.(10) Furthermore, the aqueous extract demonstrated potent inhibitory activity (ED50 = 62 mg/mL) against HIV-1 replication (KK-1 strain, freshly isolated from a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). In other in vitro studies, an aqueous extract of M. officinalis inhibited giant cell formation in co-cultures of MOLT-4 cells with and without HIV-1 infection, and showed inhibitory activity against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (ED50 = 1.6 mg/mL).(10)

Aqueous extracts of M. officinalis have been reported to inhibit protein biosynthesis in a cell-free system from rat liver cells, and it has been suggested that this effect may be due to caffeic acid and a component isolated from the glycoside fraction of the extract.(11)

The latter component appears to block the binding of the elongation factor EF-2 to ribosomes, thus terminating peptide elongation.(11)

Antimicrobial activity Antimicrobial activity of essential oil extracted from M. officinalis by steam distillation, determined using a micro-atmospheric technique, has been reported against the yeasts Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and against Pseudomonas putida, Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus luteus, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Proteus vulgaris, Shigella sonnei and Escherichia coli.(12)

Other activity In studies in mice, a hydroalcoholic extract of M. officinalis leaves administered intraperitoneally significantly reduced behavioural activity in two tests, compared with control, suggesting that the extract has sedative effects.(13) In both tests, the effect was maximum at 25 mg/kg. The same extract demonstrated peripheral analgesic activity by reducing acetic acid-induced writhing and stretching in mice when administered intraperitoneally at doses of 25–1600 mg/kg 30 minutes after intraperitoneal administration of 1.2% acetic acid solution.(13) However, no analgesic effects were observed on heat-induced pain (hotplate test) which suggests a lack of central analgesic activity. In other tests, low doses (3 and 6 mg/kg) of a hydroalcoholic extract of M. officinalis leaves administered intraperitoneally

induced sleep in mice given an infrahypnotic dose of pentobarbital.(13) By contrast, in the same battery of tests, essential oil

obtained from M. officinalis by distillation did not demonstrate sedative or sleep-inducing effects.(13)

A 30% alcoholic extract of M. officinalis demonstrated an antispasmodic effect on rat duodenum in vitro.(14)

Aqueous methanolic extracts of the aerial parts of M. officinalis demonstrated inhibition of lipid peroxidation in vitro in both enzyme-dependent and enzyme-independent systems.(15) The same tests carried out on the main known phenolic components of M. officinalis revealed that rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, luteolin and luteolin-7-O-glucoside were more potent inhibitors of enzyme-dependent lipid peroxidation than enzymeindependent lipid peroxidation.

Clinical studies

Antiviral effects The effects of a topical preparation of a standardised aqueous extract of M. officinalis leaves (drug/ extract 70 : 1) have been investigated in herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. In an open, multicentre study, 115 patients with

Figure 3 Melissa – dried drug substance (leaf and flowering tops).

HSV infection of the skin or transitional mucosa applied lemon balm leaf extract five times daily for a maximum of 14 days; complete healing of lesions was achieved after eight days of treatment in 96% of participants.(16, 17) Subsequently, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 116 patients with HSV infection of the skin or transitional mucosa reported statistically significant differences between the treatment (applied locally two to four times daily over 5–10 days) and placebo groups for some (including redness, physician's assessment, patient's assessment), but not all, outcome measures (e.g. extent of scabbing, vesication, pain).(17) Another randomised, double-blind trial that involved 66 patients with an acute episode of recurrent (at least four episodes per year) herpes simplex

labialis compared verum cream (applied on the affected area four times daily over five days) with placebo.(18) There was a

significant difference in the primary outcome measure – symptom score after two days' treatment – between the two groups (p = 0.042). However, further investigation is required to determine if time to recurrence is prolonged.

Sedative effects The acute sedative effects of several plant extracts, including a preparation of M. officinalis leaves, were explored in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involving 12 healthy volunteers.(19) M. officinalis extract 1200 mg was administered orally as a single dose about two hours before administration of caffeine 100 mg. Melissa extract was one of the extracts tested that showed least effects on increasing tiredness (i.e. it was no different from placebo) as measured using a visual analogue scale score for alertness.

Several other studies have investigated the sedative effects of combination preparations containing extracts of lemon balm and valerian (Valeriana officinalis). A randomised, double-blind trial involving healthy volunteers who received Songha Night (V. officinalis root extract 120 mg and M. officinalis leaf extract 80 mg) three tablets daily taken as one dose 30 minutes before bedtime for 30 days (n = 66), or placebo (n = 32), found that the proportion of participants reporting an improvement in sleep quality was significantly greater for the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (33.3% versus 9.4%, respectively; p = 0.04).(20) However, analysis of visual analogue scale scores revealed only a slight but statistically non-significant improvement in sleep quality in both groups over the treatment period. Another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving patients with insomnia who received Euvegal forte (valerian extract 160 mg and lemon balm extract 80 mg) two tablets daily for two weeks reported significant improvements in sleep quality in recipients of the herbal preparation, compared with placebo recipients.(21) A placebo-controlled study involving 'poor sleepers' who received Euvegal forte reported significant improvements in sleep efficiency and in sleep stages three and four in the treatment group, compared with placebo recipients.(22)

Other studies have investigated the sedative effects of combination preparations of extracts of lemon balm, valerian and hops (Humulus lupulus). In an open, uncontrolled, multicentre study, 225 individuals who were experiencing nervous agitation and/or difficulties falling asleep and achieving uninterrupted sleep were treated for two weeks with a combination preparation containing extracts of valerian root, hop grains and lemon balm leaves.(23) Significant improvements in the severity and frequency of symptoms were reported, compared with the pretreatment period. Difficulties falling asleep, difficulties sleeping through the night, and nervous agitation were improved in 89%, 80% and 82% of participants, respectively.

Melissa |

427 |

Side-effects, Toxicity

Small-scale, short-term (two weeks' duration) studies investigating |

|

|

the sedative effects of oral combination preparations containing |

|

|

lemon balm extract indicate that these preparations are well- |

|

|

tolerated and do not appear to induce a 'hangover effect'. In an |

|

|

open, uncontrolled, multicentre study, 225 individuals who were |

|

|

experiencing nervous agitation and/or difficulties falling asleep |

|

|

and achieving uninterrupted sleep were treated for two weeks with |

|

|

a combination preparation containing extracts of valerian root, |

|

|

hop grains and lemon balm leaves.(23) The tolerability of the |

|

|

preparation was rated as 'good' or 'very good' by 97% of physicians |

|

|

and 96% of patients. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo- |

|

|

controlled trial involving healthy volunteers who received Songha |

|

|

Night (V. officinalis root 120 mg and M. officinalis leaf extract |

|

|

80 mg) three tablets daily for 30 days (n = 66), or placebo (n = 32), |

|

|

the proportion of volunteers reporting adverse events was similar |

|

|

in both groups (around 28%).(20) Sleep disturbances and tiredness |

|

|

were the most common adverse events reported during the study. |

|

|

(Note: the study was designed to assess the effects of the |

|

|

preparation on sleep quality.) No severe adverse events were |

|

|

reported. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study |

|

|

involving 48 adults assessed the adverse effects of two weeks' |

|

|

treatment with a combination preparation (valerian root extract |

|

|

95 mg, hops extract 15 mg and lemon balm leaf extract 85 mg) |

|

|

taken alone or with alcohol.(24) Compared with placebo, the herbal |

|

|

combination preparation did not have adverse effects on |

|

|

performance (e.g. concentration, vigilance). Furthermore, co- |

|

|

administration of the combination preparation with alcohol did |

|

|

not have potentiating effects on performance parameters.(24) No |

M |

|

serious adverse events were observed during the study. |

||

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a |

||

topical preparation containing 1% dried extract of M. officinalis |

|

|

leaves (drug/extract 70 : 1) involving 116 patients with HSV |

|

|

infection of the skin or transitional mucosa reported that there |

|

|

were no statistically significant differences between the treatment |

|

|

and placebo groups with regard to the frequency of adverse |

|

|

effects.(17) Adverse events reported were minor (irritation, burning |

|

|

sensation); there were no reports of allergic contact reactions. |

|

|

However, skin sensitisation may occur with melissa.(G58) |

|

|

Contra-indications, Warnings |

|

|

|

|

|

None documented. |

|

|

Drug interactions None documented. However, the potential for |

|

|

preparations of melissa to interact with other medicines |

|

|

administered concurrently, particularly those with similar or |

|

|

opposing effects, should be considered. |

|

|

Pregnancy and lactation In view of the lack of toxicity data, |

|

|

oral administration of lemon balm during pregnancy and lactation |

|

|

should be avoided. Topical use of lemon balm during pregnancy |

|

|

and lactation is unlikely to be problematic. |

|

|

Preparations |

|

|

Proprietary single-ingredient preparations |

|

|

Austria: Lomaherpan. Belgium: Dormiplant. Chile: Citromel. |

|

|

Czech Republic: Lakinal; Medovka Lekarska; Medunkovy, |

|

|

Medunkova. Germany: Gastrovegetalin; Lomaherpan; Me- |

|

|

Sabona; Sedinfant. Russia: Novo-Passit (Ново-Пассит). Swit- |

|

|

zerland: Valverde Boutons de fievre creme. |

|

|

428 Melissa

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Nervocalm; Valeriana Oligoplex. Australia: Natural Deep Sleep. Austria: Abdomilon N; Baldracin; Euvekan; Mariazeller; Passedan; Passelyt; Sedogelat; Songha; Species nervinae; The Chambard-Tee; Wechseltee St Severin. Belgium: Songha. Brazil: Balsamo Branco; Calmapax; Elixir de Passiflora; Passaneuro; Passilex; Sonhare. Canada: Herbal Sleep Well. Chile: Melipass; Recalm. Czech Republic: Alvisan Neo; Baldracin; Blahungstee N; Eugastrin; Euvekan; Fytokliman Planta; Hertzund Kreislauftee; Hypotonicka; Melaton; Nervova Cajova Smes; Nontusyl; Novo-Passit; Persen; SchlafNerventee N; Songha Night; Species Nervinae Planta; Valofyt Neo. France: Biocarde; Dystolise; Elixir Bonjean; Mediflor Tisane Calmante Troubles du Sommeil No 14; Mediflor Tisane Circulation du Sang No 12; Vagostabyl. Germany: Abdomilon; Abdomilon N; Baldriparan N Stark; Dormarist; Dr. Scheffler Bergischer Krautertee Nervenund Beruhigungstee; Euvegal Entspannungsund Einschlaftropfen; Gutnacht; Gutnacht; Heumann Beruhigungstee Tenerval; Iberogast; Jukunda Melis- sen-Krautergeist N; Klosterfrau Melisana; Lindofluid N; MeSabona plus; Melissengeist; Oxacant-sedativ; Pascosedon; Phytonoctu; Plantival novo; Pronervon Phyto; Schlafund Nerventee; Sedacur; Sedariston plus; Stullmaton. Hungary: Euvekan. Israel: Songha Night. Italy: Colimil; Dormiplant; Emmenoiasi; Sedatol; Tisana Kelemata. Mexico: Nordimenty; Plantival. New Zealand: Botanica Hayfever; Mr Nits. Portugal: Erpecalm; Songha. Russia: Doppelherz Melissa (Доппельгерц Мелисса); Doppelherz Vitalotonik (Доппельгерц Виталото-

MContra Tussim Drops. Spain: Agua del Carmen; Caramelos Agua del Carmen; Himelan; Jaquesor; Mesatil; Natusor Aerofane; Natusor Jaquesan; Nervikan; Relana; Resolutivo Regium; Solucion Schoum. Switzerland: Arterosan Plus; Baldriparan; Cardiaforce; Carmol; Dormiplant; Dragees pour la detente nerveuse; Gastrosan; Hyperiforce comp; Iberogast; Relaxane; Relaxo; Songha Night; Soporin; Tisane calmante pour les enfants; Tisane favorisant l'allaitement; Tisane pour l'estomac; Tisane pour le coeur et la circulation; Tisane pour le sommeil et les nerfs; Tisane pour nourissons et enfants; Valverde Detente dragees; Valviska. UK: Boots Alternatives Sleep Well; Boots Sleepeaze Herbal Tablets; Melissa Comp.;

Napiers Echinacea Tea; Valerina Day Time; Valerina Day- Time; Valerina Night-Time; Valerina Night-Time.ник); Persen (Персен). South Africa: Melissengeist; Spiritus

References

1Tittel G et al. Über die chemische Zusammensetzung von Melissenölen. Planta Med 1982; 46: 91–98.

2Carnat AP et al. The aromatic and polyphenolic composition of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L. subsp. officinalis) tea. Pharm Acta Helv

1998; 72: 301–305.

3Sarer E, Kökdil G. Constituents of the essential oil from Melissa officinalis. Planta Med 1991; 57: 89–90.

4 Heitz A et al. Luteolin 30-glucuronide, the major flavonoid from

Melissa officinalis subsp. officinalis. Fitoterapia 2000; 71: 201–202.

5Tagashira M, Ohtake Y. A new antioxidative 1,3-benzodioxole from

Melissa officinalis. Planta Med 1998; 64: 555–558.

6Kucera LS, Herrmann ECJr. Antiviral substances in plants of the mint family (Labiatae). I Tannin of Melissa officinalis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1967; 124: 865–869.

7Herrmann ECJr, Kucera LS. Antiviral substances in plants of the mint family (Labiatae). II Nontannin polyphenol of Melissa officinalis.

Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1967; 124: 869–874.

8May G, Willuhn G. Antivirale Wirkung wässriger Pflanzenextrakte in Gewebekulturen. Arzneimittelforschung 1978; 28: 1–7.

9Dimitrova Z et al. Antiherpes effect of Melissa officinalis L. extracts.

Acta Microbiol Bulg 1993; 29: 65–72.

10Yamasaki K et al. Anti-HIV-1 activity of herbs in Labiatae. Biol Pharm Bull 1998; 21: 829–833.

11Chlabicz J, Galasinski W. The components of Melissa officinalis L. that influence protein biosynthesis in-vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol 1986; 38: 791–794.

12Larrondo JV et al. Antimicrobial activity of essences from labiates. Microbios 1995; 82: 171–2.

13Soulimani R et al. Neurotropic action of the hydroalcoholic extract of

Melissa officinalis in the mouse. Planta Med 1991; 57: 105–109.

14Soulimani R et al. Recherche de l'activitébiologique de Melissa officinalis L. sur le système nerveux central de la souris in vivo et le duodenum de rat in vitro. Plantes Méd Phytothér 1993; 26: 77–85.

15Hohmann J et al. Protective effects of the aerial parts of Salvia officinalis, Melissa officinalis and Lavandula angustifolia and their constituents against enzyme-dependent and enzyme-independent lipid peroxidation. Planta Med 1999; 65: 576–578.

16Wölbling RH, Milbradt R. Klinik und Therapie des Herpes simplex. Therapiewoche 1984; 34: 1193–1200.

17Wölbling RH, Leonhardt K. Local therapy of herpes simplex with dried extract from Melissa officinalis. Phytomedicine 1994; 1: 25–31.

18Koytchev R et al. Balm mint extract (Lo-701) for topical treatment of recurring Herpes labialis. Phytomedicine 1999; 6: 225–230.

19Schulz H et al. The quantitative EEG as a screening instrument to identify sedative effects of single doses of plant extracts in comparison with diazepam. Phytomedicine 1998; 5: 449–458.

20Cerny A, Schmid K. Tolerability and efficacy of valerian/lemon balm in healthy volunteers (a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study). Fitoterapia 1999; 70: 221–228.

21Dressing H et al. Verbesserung der Schlafqualität mit einem hochdosierten Baldrian-Melisse-Präparat. Eine plazebokontrollierte Doppelblindstudie. Psychopharmakotherapie 1996; 3: 123–130.

22Dressing H et al. Baldrian-Melisse-Kombinationen versus Benzodiazepin. Bei Schlafstörungen gleichwertig? Therapiewoche 1992; 42: 726–736.

23Orth-Wagner S et al. Phytosedativum gegen Schlafstärungen. Z Phytother 1995; 16: 147–156.

24Herberg K-W. Nebenwirkungen pflanzlicher Beruhigungsmittel. Z Allgemeinmed 1996; 72: 234–240.