Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Cerebral hypoxia. After recovery from hypoxia (brought on by such conditions as carbon monoxide poisoning or acute respiratory failure), the patient may experience total amnesia for the event, along with sensory disturbances, such as numbness and tingling.

Head trauma. Depending on the trauma’s severity, amnesia may last for minutes, hours, or longer. Usually, the patient experiences brief retrograde and longer anterograde amnesia as well as persistent amnesia about the traumatic event. Severe head trauma can cause permanent amnesia or difficulty retaining recent memories. Related findings may include altered respirations and LOC; headache; dizziness; confusion; visual disturbances, such as blurred or double vision; and motor and sensory disturbances, such as hemiparesis and paresthesia, on the side of the body opposite the injury.

Herpes simplex encephalitis. Recovery from herpes simplex encephalitis commonly leaves the patient with severe and possibly permanent amnesia. Associated findings include signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation, such as headache, fever, and altered LOC, along with seizures and various motor and sensory disturbances (such as paresis, numbness, and tingling).

Hysteria. Hysterical amnesia, a complete and long-lasting memory loss, begins and ends abruptly and is typically accompanied by confusion.

Seizures. In temporal lobe seizures, amnesia occurs suddenly and lasts for several seconds to minutes. The patient may recall an aura or nothing at all. An irritable focus on the left side of the brain primarily causes amnesia for verbal memories, whereas an irritable focus on the right side of the brain causes graphic and nonverbal amnesia. Associated signs and symptoms may include decreased LOC during the seizure, confusion, abnormal mouth movements, and visual, olfactory, and auditory hallucinations.

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Retrograde and anterograde amnesia can become permanent without treatment in this syndrome. Accompanying signs and symptoms include apathy, an inability to concentrate or to put events into sequence, and confabulation to fill memory gaps. The syndrome may also cause diplopia, decreased LOC, headache, ataxia, and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, such as numbness and tingling.

Other Causes

Drugs. Anterograde amnesia can be precipitated by general anesthetics, especially fentanyl, halothane, and isoflurane; barbiturates, most commonly pentobarbital and thiopental; and certain benzodiazepines, especially triazolam.

Electroconvulsive therapy. The sudden onset of retrograde or anterograde amnesia occurs with electroconvulsive therapy. Typically, the amnesia lasts for several minutes to several hours, but severe, prolonged amnesia occurs with treatments given frequently over a prolonged period.

Temporal lobe surgery. Usually performed on only one lobe, this surgery causes brief, slight amnesia. However, removal of both lobes results in permanent amnesia.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, EEG, or cerebral angiography.

Provide reality orientation for the patient with retrograde amnesia, and encourage his family to help by supplying familiar photos, objects, and music.

Adjust your patient teaching techniques for the patient with anterograde amnesia because he can’t acquire new information. Include his family in teaching sessions. In addition, write down all instructions — particularly medication dosages and schedules — so the patient won’t have to rely on his memory.

If the patient has severe amnesia, consider basic needs, such as safety, elimination, and nutrition. If necessary, arrange for placement in an extended-care facility.

Patient Counseling

Adjust your patient counseling techniques for the patient with anterograde amnesia because he can’t acquire new information. Supply the patient with familiar items, such as music and photos, to help him become oriented. Write out patient medication schedules to avoid depending on memory.

Pediatric Pointers

A child who suffers from amnesia during seizures may be mistakenly labeled as “learning disabled.” To prevent this mislabeling, stress the importance of adhering to the prescribed drug schedule, and discuss ways that the child, his parents, and his teachers can cope with amnesia.

REFERENCES

Liang, J. F., Shen, A. L., & Lin S. K. (2009). Bilateral hippocampal abnormalities on diffusion-weighted MRI in transient global amnesia: Report of a case. Acta Neurologica Taiwan, 18(2),127–129.

Yang, Y., Kim, J. S., Kim, S., Kim, Y. K. , Kwak, Y. T. , & Han, I. W. (2009). Cerebellar hypoperfusion during transient global amnesia: An MRI and oculographic study. Journal of Clinical Neurology, 5(2),74–80.

Analgesia

(See Also Abdominal)

Analgesia, the absence of sensitivity to pain, is an important sign of central nervous system disease, commonly indicating a specific type and location of spinal cord lesion. It always occurs with loss of temperature sensation (thermanesthesia) because these sensory nerve impulses travel together in the spinal cord. It can also occur with other sensory deficits — such as paresthesia, loss of proprioception and vibratory sense, and tactile anesthesia — in various disorders involving the peripheral nerves, spinal cord, and brain. However, when accompanied only by thermanesthesia, analgesia points to an incomplete lesion of the spinal cord.

Analgesia can be classified as partial or total below the level of the lesion and as unilateral or bilateral, depending on the cause and level of the lesion. Its onset may be slow and progressive with a tumor or abrupt with trauma. Transient in many cases, analgesia may resolve spontaneously.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Suspect spinal cord injury if the patient complains of unilateral or bilateral analgesia over a large body area, accompanied by paralysis. Immobilize his spine in proper alignment, using a cervical collar and a long backboard, if possible. If a collar or backboard isn’t available,

position the patient in a supine position on a flat surface and place sandbags around his head, neck, and torso. Use correct technique and extreme caution when moving him to prevent exacerbating spinal injury. Continuously monitor respiratory rate and rhythm, and observe him for accessory muscle use because a complete lesion above the T6 level may cause diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle paralysis. Have an artificial airway and a handheld resuscitation bag on hand, and be prepared to initiate emergency resuscitation measures in case of respiratory failure.

History and Physical Examination

After you’re satisfied that the patient’s spine and respiratory status are stabilized — or if the analgesia isn’t severe and isn’t accompanied by signs of spinal cord injury — perform a physical examination and baseline neurologic evaluation. First, take the patient’s vital signs and assess his level of consciousness. Then, test pupillary, corneal, cough, and gag reflexes to rule out brain stem and cranial nerve involvement. If the patient is conscious, evaluate his speech, gag reflex, and ability to swallow.

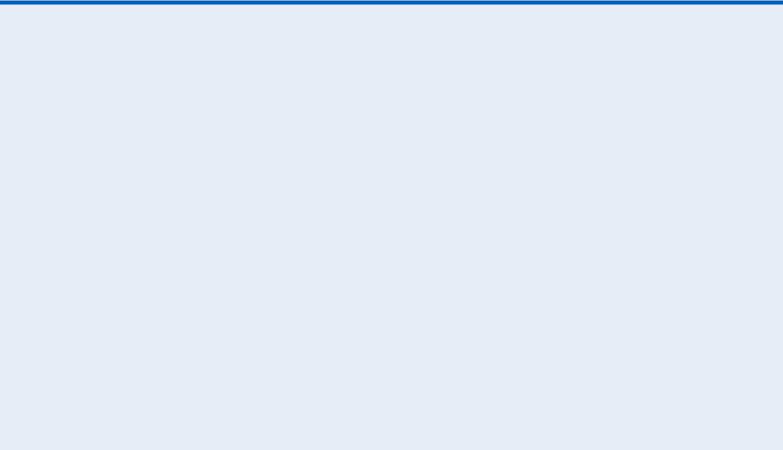

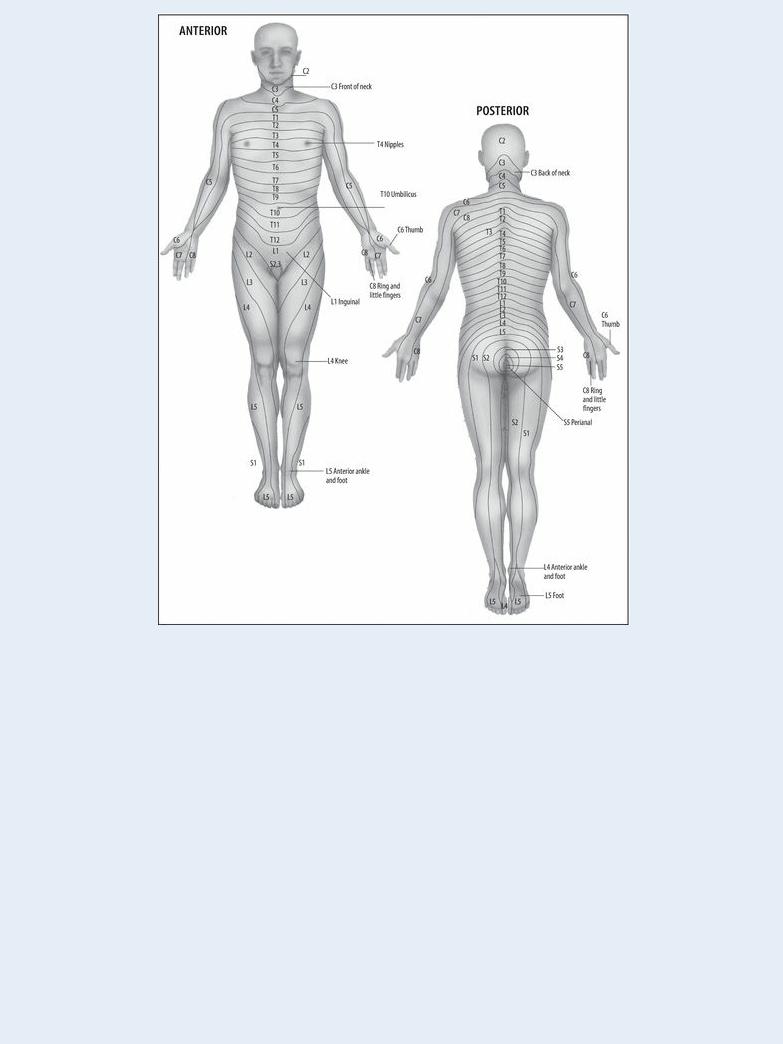

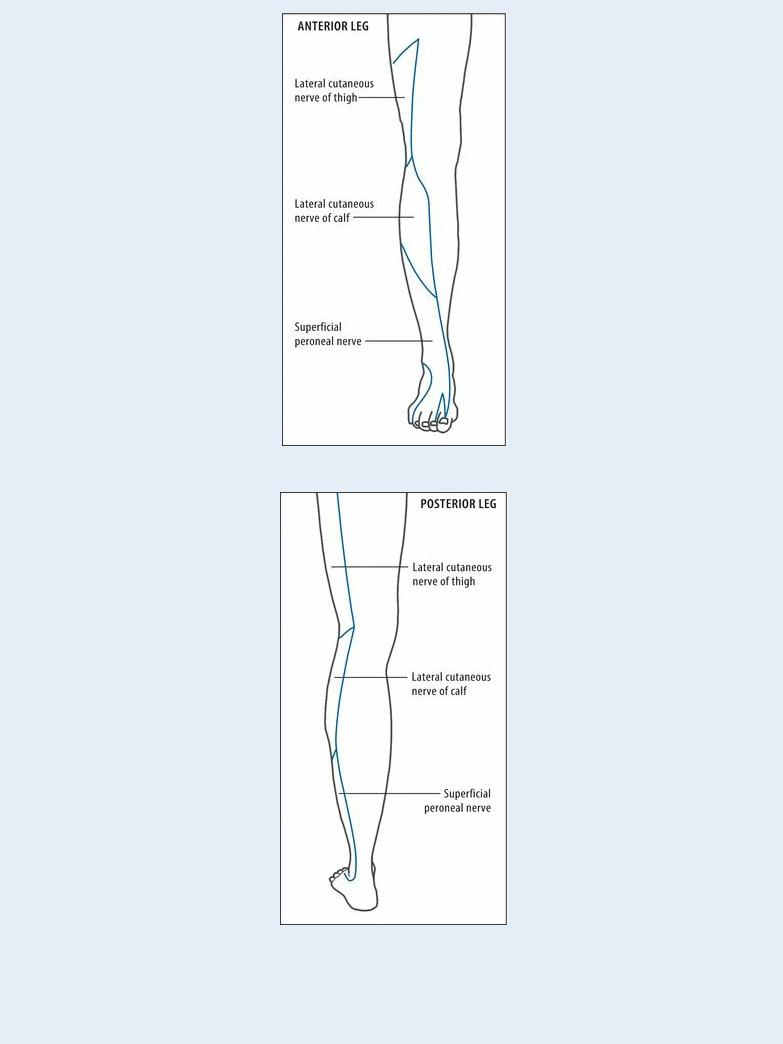

If possible, observe the patient’s gait and posture, and assess his balance and coordination. Evaluate muscle tone and strength in all extremities. Test for other sensory deficits over all dermatomes (individual skin segments innervated by a specific spinal nerve) by applying light tactile stimulation with a tongue depressor or cotton swab. Perform a more thorough check of pain sensitivity, if necessary, using a pin. (See Testing for Analgesia , pages 42 and 43.) Also, test temperature sensation over all dermatomes, using two test tubes — one filled with hot water and the other with cold water. In each arm and leg, test vibration sense (using a tuning fork), proprioception, and superficial and deep tendon reflexes. Check for increased muscle tone by extending and flexing the patient’s elbows and knees as he tries to relax.

EXAMINATION TIP Testing for Analgesia

EXAMINATION TIP Testing for Analgesia

By carefully and systematically testing the patient’s sensitivity to pain, you can determine whether his nerve damage has a segmental or peripheral distribution and help locate the causative lesion.

Tell the patient to relax, and explain that you’re going to lightly touch areas of his skin with a small pin. Have him close his eyes. Apply the pin firmly enough to produce pain without breaking the skin. (Practice on yourself first to learn how to apply the correct pressure.)

Starting with the patient’s head and face, move down his body, pricking his skin on alternating sides. Have the patient report when he feels pain. Use the blunt end of the pin occasionally, and vary your test pattern to gauge the accuracy of his response.

Document your findings thoroughly, clearly marking areas of lost pain sensation either on a dermatome chart (shown at left) or on appropriate peripheral nerve diagrams (shown below).

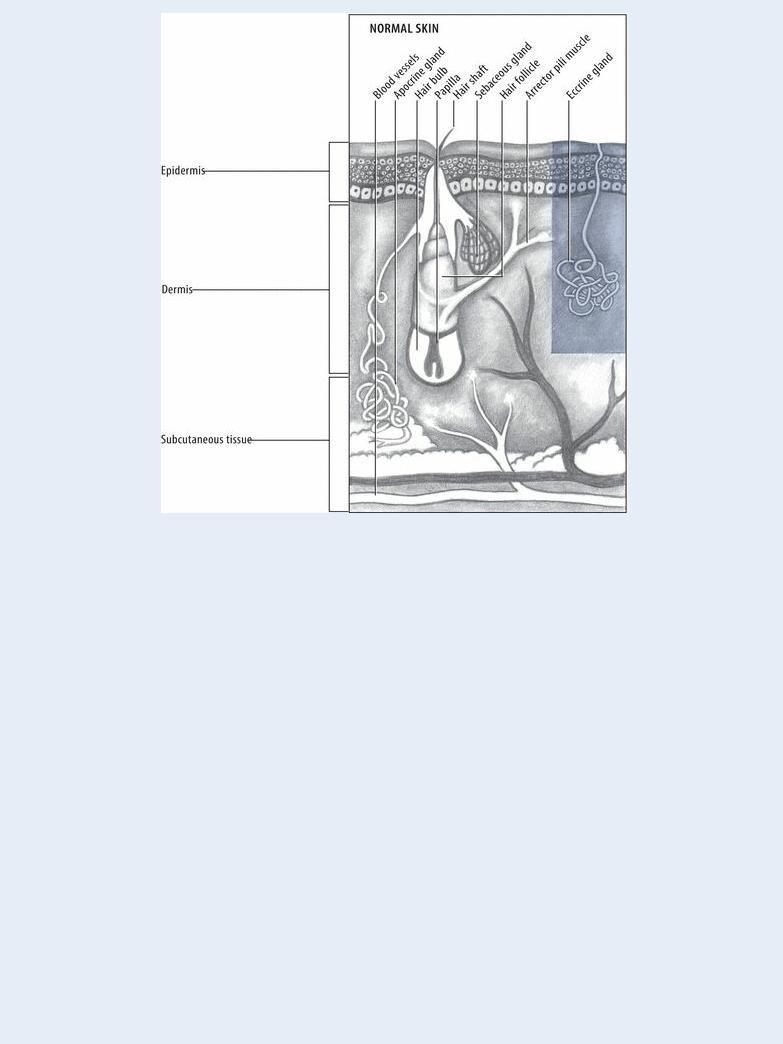

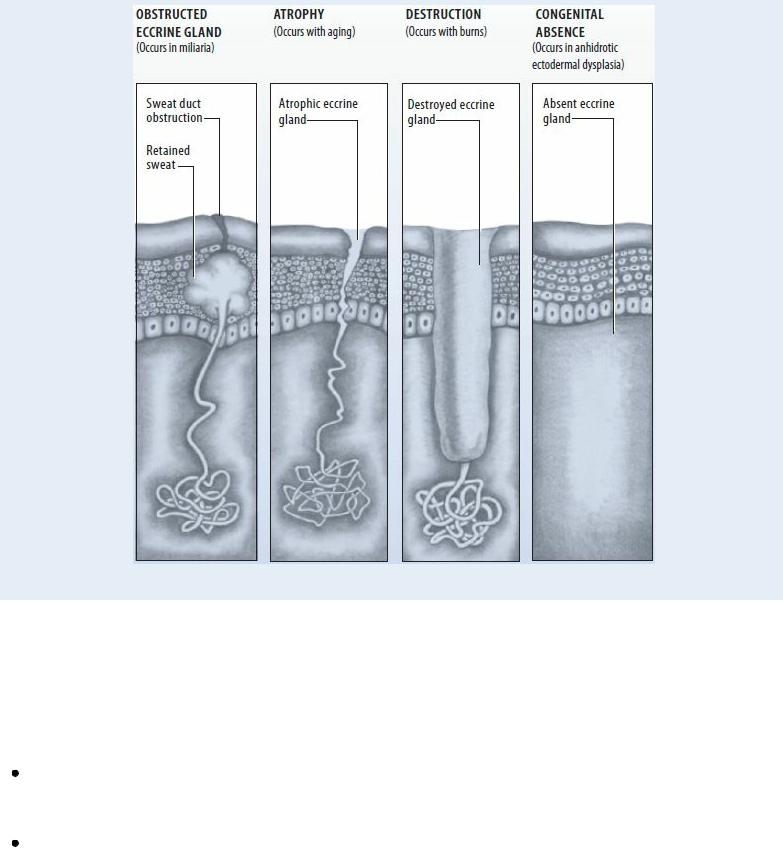

Eccrine Dysfunction in Anhidrosis

Eccrine glands, located over most of the skin, help regulate body temperature by secreting sweat. Any change or dysfunction in these glands can result in anhidrosis of varying severity. These illustrations show a normal eccrine gland and some common abnormalities.

Focus your history taking on the onset of analgesia (sudden or gradual) and on any recent trauma — a fall, sports injury, or automobile accident. Obtain a complete medical history, noting especially any incidence of cancer in the patient or his family.

Medical Causes

Anterior cord syndrome. With anterior cord syndrome, analgesia and thermanesthesia occur bilaterally below the level of the lesion, along with flaccid paralysis and hypoactive deep tendon reflexes.

Central cord syndrome. Typically, analgesia and thermanesthesia occur bilaterally in several dermatomes, in many cases extending in a capelike fashion over the arms, back, and shoulders. Early weakness in the hands progresses to weakness and muscle spasms in the arms and shoulder girdle. Hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and spastic weakness of the legs may develop. However, if the lesion affects the lumbar spine, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes and flaccid weakness may persist in the legs.

With brain stem involvement, additional findings include facial analgesia and thermanesthesia, vertigo, nystagmus, atrophy of the tongue, and dysarthria. The patient may also have dysphagia, urine retention, anhidrosis, decreased intestinal motility, and hyperkeratosis.

Spinal cord hemisection. Contralateral analgesia and thermanesthesia occur below the level of the lesion. In addition, loss of proprioception, spastic paralysis, and hyperactive deep tendon reflexes develop ipsilaterally. The patient may also experience urine retention with overflow incontinence.

Other Causes

Drugs. Analgesia may occur with use of a topical or local anesthetic, although numbness and tingling are more common.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for spinal X-rays, and maintain spinal alignment and stability during transport to radiology.

Focus your care on preventing further injury to the patient because analgesia can mask injury or developing complications. Prevent formation of pressure ulcers through meticulous skin care, massage, use of lamb’s wool pads, and frequent repositioning, especially when significant motor deficits hamper the patient’s movement.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient to test the bath water temperature at home using a thermometer or a body part with intact sensation. Explain all tests and procedures, and teach the patient about the diagnosis, once established, and about the treatment plan.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a child may have difficulty describing analgesia, observe him carefully during the assessment for nonverbal clues to pain, such as facial expressions, crying, and retraction from stimuli. Remember that pain thresholds are high in infants, so your assessment findings may not be reliable. Also, remember to test bathwater carefully for a child who’s too young to test it himself.

REFERENCES

Pedicelli, A, Verdolotti, T . , Pompucci, A. , Desiderio, F. , D’Argento, F. Colosimo, C., & Bonomo, L. (2011) . Interventional spinal procedures guided and controlled by a 3D rotational angiographic unit. Skeletal Radiology, 40(12), 1595–1601.

Schneider, G. M., Jull, G., Thomas, K., & Salo, P. (2012). Screening of patients suitable for diagnostic cervical facet joint blocks—A role for physiotherapists. Manual Therapy, 17(2), 180–183.

Anhidrosis

Anhidrosis, an abnormal deficiency of sweat, can be classified as generalized (complete) or localized (partial). Generalized anhidrosis can lead to life-threatening impairment of thermoregulation. Localized anhidrosis rarely interferes with thermoregulation because it affects only a small percentage of the body’s eccrine (sweat) glands.

Anhidrosis results from neurologic and skin disorders; congenital, atrophic, or traumatic changes to sweat glands; and the use of certain drugs. Neurologic disorders disturb central or peripheral

nervous pathways that normally activate sweating, causing retention of excess body heat and perspiration. The absence, obstruction, atrophy, or degeneration of sweat glands can produce anhidrosis at the skin surface, even if neurologic stimulation is normal. (See Eccrine Dysfunction in Anhidrosis, pages 46 and 47.)

Anhidrosis may go unrecognized until significant heat or exertion fails to raise sweat. However, localized anhidrosis commonly provokes compensatory hyperhidrosis in the remaining functional sweat glands — which, in many cases, is the patient’s chief complaint.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect anhidrosis in a patient whose skin feels hot and flushed, ask him if he’s also experiencing nausea, dizziness, palpitations, and substernal tightness. If he is, quickly take his rectal temperature and other vital signs and assess his level of consciousness (LOC). If a rectal temperature higher than 102.2°F (39°C) is accompanied by tachycardia, tachypnea, and altered blood pressure and LOC, suspect life-threatening anhidrotic asthenia (heatstroke). Start rapid cooling measures, such as immersing him in ice or very cold water and giving I.V. fluid replacements. Continue these measures, and check his vital signs and neurologic status frequently, until his temperature drops below 102°F (38.9°C). Then, place him in an air-conditioned room.

History and Physical Examination

If anhidrosis is localized or if the patient reports local hyperhidrosis or unexplained fever, take a brief history. Ask the patient to characterize his sweating during heat spells or strenuous activity. Does he usually sweat slightly or profusely? Ask about recent prolonged or extreme exposure to heat and about the onset of anhidrosis or hyperhidrosis. Obtain a complete medical history, focusing on neurologic disorders; skin disorders, such as psoriasis; autoimmune disorders, such as scleroderma; systemic diseases that can cause peripheral neuropathies, such as diabetes mellitus; and drug use.

Inspect skin color, texture, and turgor. If you detect skin lesions, document their location, size, color, texture, and pattern.

Medical Causes

Anhidrotic asthenia (heatstroke). A life-threatening disorder, anhidrotic asthenia causes acute, generalized anhidrosis. In early stages, sweating may still occur, and the patient may be rational, but his rectal temperature may already exceed 102.2°F (39°C). Associated signs and symptoms include severe headache and muscle cramps, which later disappear, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, palpitations, substernal tightness, and elevated blood pressure followed by hypotension. Within minutes, anhidrosis and hot, flushed skin develop, accompanied by tachycardia, tachypnea, and confusion progressing to seizure or loss of consciousness.

Burns. Depending on their severity, burns may cause permanent anhidrosis in affected areas as well as blistering, edema, and increased pain or loss of sensation.

Miliaria crystallina. This usually innocuous form of miliaria causes anhidrosis and tiny, clear, fragile blisters, usually under the arms and breasts.