Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

(See Also Cough, Barking and Cough, Productive)

A nonproductive cough is a noisy, forceful expulsion of air from the lungs that is dry, doesn’t bring up any mucus, and may yield a scant amount of sputum. It’s one of the most common complaints of patients with respiratory disorders.

Coughing is a protective mechanism that clears airway passages. However, a nonproductive cough is ineffective and can cause damage, such as airway collapse or rupture of alveoli or blebs. A nonproductive cough that later becomes productive is a classic sign of progressive respiratory disease, such as pneumonia.

The cough reflex generally occurs when mechanical, chemical, thermal, inflammatory, or psychogenic stimuli activate cough receptors. (See Reviewing the Cough Mechanism, page 188.) However, external pressure — for example, from subdiaphragmatic irritation or a mediastinal tumor

— can also induce it, as well as voluntary expiration of air, which occasionally occurs as a nervous habit. Certain drugs, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, may also cause a nonproductive cough.

A nonproductive cough may occur in paroxysms and can worsen by becoming more frequent. An acute cough has a sudden onset and may be self-limiting; a cough that persists beyond 1 month is considered chronic and commonly results from cigarette smoking.

Someone with a chronic nonproductive cough may downplay or overlook it or accept it as normal. In fact, he generally won’t seek medical attention unless he has other symptoms. A foreign body in a child’s external auditory canal may result in a cough. Always examine the child’s ears.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when his cough began and whether body position, the time of day, or a specific activity affects it. How does the cough sound — harsh, brassy, dry, or hacking? Try to determine if the cough is related to smoking or a chemical irritant. If the patient smokes or has smoked, note the number of packs smoked daily multiplied by years (“pack-years”). Next, ask about the frequency and intensity of the coughing. If he has pain associated with coughing, breathing, or activity, when did it begin? Where is it located?

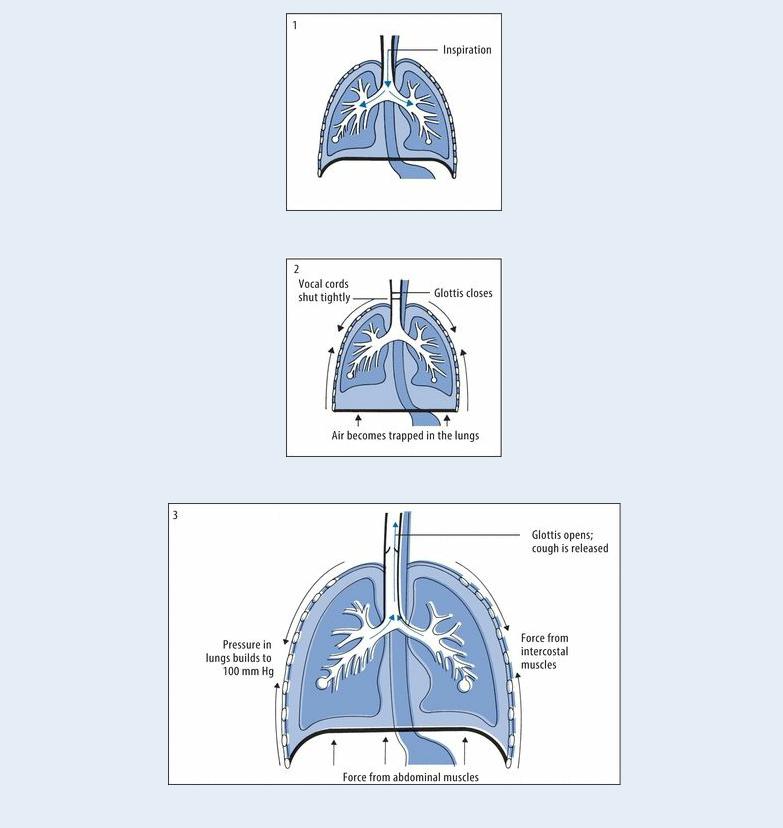

Reviewing the Cough Mechanism

Cough receptors are thought to be located in the nose, sinuses, auditory canals, nasopharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, pleurae, diaphragm and, possibly, the pericardium and GI tract. When a cough receptor is stimulated, the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves transmit the impulse to the “cough center” in the medulla. From there, the impulse is transmitted to the larynx and to the intercostal and abdominal muscles. Deep inspiration (1) is followed by closure of the glottis (2), relaxation of the diaphragm, and contraction of the abdominal and intercostal muscles. The resulting increased pressure in the lungs opens the glottis to release the forceful, noisy expiration known as a cough (3).

Ask the patient about recent illness (especially a cardiovascular or pulmonary disorder), surgery, or trauma. Also, ask about hypersensitivity to drugs, foods, pets, dust, or pollen. Find out which medications the patient takes, if any, and ask about recent changes in schedule or dosages. Also, ask about recent changes in his appetite, weight, exercise tolerance, or energy level and recent exposure to irritating fumes, chemicals, or smoke.

As you’re taking his history, observe the patient’s general appearance and manner: Is he agitated, restless, or lethargic; pale, diaphoretic, or flushed; anxious, confused, or nervous? Also, note whether he’s cyanotic or has clubbed fingers or peripheral edema.

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

Because of the fear of being known as someone with tuberculosis (TB), the patient may be reluctant to provide information about his signs and symptoms such as a cough. Ask the patient at risk for TB — one born in another country, in contact with acute TB, or with highrisk behaviors — about potential TB exposure.

Next, perform a physical examination. Start by taking the patient’s vital signs. Check the depth and rhythm of his respirations, and note if wheezing or “crowing” noises occur with breathing. Feel the patient’s skin: Is it cold or warm, clammy, or dry? Check his nose and mouth for congestion, inflammation, drainage, or signs of infection. Inspect his neck for distended jugular veins and tracheal deviation, and palpate for masses or enlarged lymph nodes.

Examine his chest, observing its configuration and looking for abnormal chest wall motion. Do you note any retractions or use of accessory muscles? Percuss for dullness, tympany, or flatness. Auscultate for wheezing, crackles, rhonchi, pleural friction rubs, and decreased or absent breath sounds. Finally, examine his abdomen for distention, tenderness, masses, or abnormal bowel sounds.

Medical Causes

Airway occlusion. Partial occlusion of the upper airway produces a sudden onset of dry, paroxysmal coughing. The patient is gagging, wheezing, and hoarse, with stridor, tachycardia, and decreased breath sounds.

Anthrax (inhalation). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease that’s caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Although the disease most commonly occurs in wild and domestic grazing animals, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, the spores can live in the soil for many years. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Most natural cases occur in agricultural regions worldwide. Anthrax may occur in the cutaneous, inhalation, or GI form.

Inhalation anthrax is caused by inhaling aerosolized spores. Initial signs and symptoms are flulike and include a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain. The disease generally occurs in two stages, with a period of recovery after the initial signs and symptoms. The second stage develops abruptly with rapid deterioration marked by a fever, dyspnea, stridor, and hypotension generally leading to death within 24 hours. Radiologic findings include mediastinitis and symmetric mediastinal widening.

Aortic aneurysm (thoracic). Pressure of an aortic aneurysm on the trachea may cause a brassy cough with dyspnea, hoarseness, wheezing, and a substernal ache in the shoulders, lower back, or abdomen. The patient may also have facial or neck edema, jugular vein distention, dysphagia, prominent veins over his chest, stridor, and, possibly, paresthesia or neuralgia.

Asthma. Asthma attacks typically occur at night, starting with a nonproductive cough and mild wheezing; this progresses to severe dyspnea, audible wheezing, chest tightness, and a cough that produces thick mucus. Other signs include apprehension, rhonchi, prolonged expirations, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions on inspiration, accessory muscle use, flaring nostrils, tachypnea, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and flushing or cyanosis.

Atelectasis. As lung tissue deflates, it stimulates cough receptors, causing a nonproductive

cough. The patient may also have pleuritic chest pain, anxiety, dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia. His skin may be cyanotic and diaphoretic, his breath sounds may be decreased, his chest may be dull on percussion, and he may exhibit inspiratory lag, substernal or intercostal retractions, decreased vocal fremitus, and tracheal deviation toward the affected side.

Avian flu. The avian flu, also known as the bird flu (H5N1), is a virus that is normally found in sick birds and poultry and does not normally infect humans. However, the first reported cases of human infection with H5N1 (the most virulent type) occurred worldwide in 1996. A nonproductive cough is characteristic of an infection with the avian flu virus as it is with conventional human influenza viruses. Accompanying symptoms include fever, sore throat, runny nose, headache, muscle aches, and conjunctivitis; viral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress are serious life-threatening complications that can occur.

Blast lung injury. Patients affected by a blast lung injury can exhibit an immediate onset of a harsh, nonproductive cough. In blast lung injury, an explosive device has been discharged and projected toward a victim, typically in war or more recently in global terrorist attacks. Depending on the composition of the explosive device, pieces of metal or aerosol chemical irritants may be involved. The patient may report complaints of chest pain, or a burning sensation about the chest or throat; difficulty breathing and speaking; shortness of breath; headache; and feeling faint. Other findings include skin tears and contusions, edema, hemorrhage of the lungs, tachypnea, hypoxia, wheezing, apnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and hemodynamic instability. Diagnostic tests include a chest X-ray and reveal a characteristic “butterfly” pattern.

Bronchitis (chronic). Bronchitis starts with a nonproductive, hacking cough that later becomes productive. Other findings include prolonged expiration, wheezing, dyspnea, accessory muscle use, barrel chest, cyanosis, tachypnea, crackles, and scattered rhonchi. Clubbing can occur in late stages.

Bronchogenic carcinoma. The earliest indicators of bronchogenic carcinoma can be a chronic, nonproductive cough; dyspnea; and vague chest pain. The patient may also be wheezing. Common cold. The common cold generally starts with a nonproductive, hacking cough and progresses to some mix of sneezing, headaches, malaise, fatigue, rhinorrhea, myalgia, arthralgia, nasal congestion, and a sore throat.

Esophageal achalasia. In esophageal achalasia, regurgitation and aspiration produce a dry cough. The patient may also have recurrent pulmonary infections and dysphagia.

Esophageal diverticula. The patient with esophageal diverticula has a nocturnal nonproductive cough, regurgitation and aspiration, dyspepsia, and dysphagia. His neck may appear swollen and have a gurgling sound. He may also exhibit halitosis and weight loss.

Esophageal occlusion. Esophageal occlusion is marked by immediate nonproductive coughing and gagging, with a sensation of something stuck in the throat. Other findings include neck or chest pain, dysphagia, and the inability to swallow.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER). A nonproductive cough associated with GER results from irritation of the larynx. This occurs when food or fluid travels backward from the stomach to the esophagus and then spills into the hypopharynx. Other symptoms include burning pain in the chest (heartburn), sore throat, hoarseness, belching, difficulty swallowing, and sometimes wheezing.

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. A nonproductive cough is common in patients with

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, which is marked by noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Other findings include a headache, myalgia, fever, nausea, and vomiting.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. With hypersensitivity pneumonitis, an acute nonproductive cough, a fever, dyspnea, and malaise usually occur 5 to 6 hours after exposure to an antigen. Interstitial lung disease. A patient with interstitial lung disease has a nonproductive cough and progressive dyspnea. He may also be cyanotic and have clubbing, fine crackles, fatigue, variable chest pain, and weight loss.

Laryngeal tumor. A mild, nonproductive cough is an early sign of a laryngeal tumor, in addition to minor throat discomfort and hoarseness. Later, dysphagia, dyspnea, cervical lymphadenopathy, stridor, and an earache may occur.

Laryngitis. In its acute form, laryngitis causes a nonproductive cough with localized pain (especially when the patient is swallowing or speaking) as well as fever and malaise. His hoarseness can range from mild to complete loss of voice.

Lung abscess. Lung abscess typically begins with a nonproductive cough, weakness, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. The patient may also exhibit diaphoresis, a fever, a headache, malaise, fatigue, crackles, decreased breath sounds, anorexia, and weight loss. Later, his cough produces large amounts of purulent, foul-smelling, and possibly bloody sputum.

Pleural effusion. A nonproductive cough along with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and decreased chest motion are characteristic of pleural effusion. Other findings include a pleural friction rub, tachycardia, tachypnea, egophony, flatness on percussion, decreased or absent breath sounds, and decreased tactile fremitus.

Pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia usually starts with a nonproductive, hacking, painful cough that rapidly becomes productive. Other findings include shaking chills, a headache, a high fever, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia, grunting respirations, nasal flaring, decreased breath sounds, fine crackles, rhonchi, and cyanosis. The patient’s chest may be dull on percussion.

With mycoplasma pneumonia, a nonproductive cough arises 2 to 3 days after the onset of malaise, a headache, and a sore throat. The cough can be paroxysmal, causing substernal chest pain. Fever commonly occurs, but the patient doesn’t appear seriously ill.

Viral pneumonia causes a nonproductive, hacking cough and the gradual onset of malaise, headache, anorexia, and a low-grade fever.

Pneumothorax. Pneumothorax is a life-threatening disorder that causes a dry cough and signs of respiratory distress, such as severe dyspnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, and cyanosis. The patient experiences sudden, sharp chest pain that worsens with chest movement as well as subcutaneous crepitation, hyperresonance or tympany, decreased vocal fremitus, and decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side.

Pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema initially causes a dry cough that progresses to a frothy or blood-tinged sputum, exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, dependent crackles, and a ventricular gallop. If pulmonary edema is severe, the patient’s respirations become more rapid and labored, with coarse diffuse crackles and coughing that produces frothy, bloody sputum.

Pulmonary embolism. A life-threatening pulmonary embolism may suddenly produce a dry cough along with dyspnea and pleuritic or anginal chest pain. Typically, however, the cough produces blood-tinged sputum. Tachycardia and a low-grade fever are also common; less common signs and symptoms include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema, and, with a

large embolus, cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention. The patient may also have a pleural friction rub, diffuse wheezing, dullness on percussion, and decreased breath sounds. Sarcoidosis. With sarcoidosis, a nonproductive cough is accompanied by dyspnea, substernal pain, and malaise. The patient may also develop fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, weight loss, tachypnea, crackles, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, skin lesions, visual impairment, difficulty swallowing, and arrhythmias.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS is an acute infectious disease of unknown etiology; however, a novel Coronavirus has been implicated as a possible cause. Although most cases have been reported in Asia (China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand), cases have cropped up in Europe and North America. The incubation period is 2 to 7 days; the illness generally begins with a fever (usually greater than 100.4°F [38°C]). Other symptoms include a headache; malaise; a dry, nonproductive cough; and dyspnea. The severity of the illness is highly variable, ranging from mild illness to pneumonia and, in some cases, progressing to respiratory failure and death.

Tracheobronchitis (acute). Initially, tracheobronchitis produces a dry cough that later becomes productive as secretions increase. Chills, a sore throat, a slight fever, muscle and back pain, and substernal tightness generally precede the cough’s onset. Rhonchi and wheezes are usually heard. Severe illness causes a fever of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C) and possibly bronchospasm, with severe wheezing and increased coughing.

Tularemia. Also known as rabbit fever, tularemia is caused by the gram-negative, non–spore- forming bacterium Francisella tularensis. It’s typically a rural disease found in wild animals, water, and moist soil. It’s transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected insect or tick, handling infected animal carcasses, drinking contaminated water, or inhaling the bacteria. It’s considered a possible airborne agent for biological warfare. Signs and symptoms following inhalation of the organism include the abrupt onset of a fever, chills, a headache, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and bronchoscopy may stimulate cough receptors and trigger coughing.

Treatments. Irritation of the carina during suctioning or deep endotracheal or tracheal tube placement can trigger a paroxysmal or hacking cough. Intermittent positive-pressure breathing or spirometry can also cause a nonproductive cough. Some inhalants, such as pentamidine, may stimulate coughing.

Special Considerations

A nonproductive, paroxysmal cough may induce life-threatening bronchospasm. The patient may need a bronchodilator to relieve his bronchospasm and open his airways. Unless he has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, you may have to give an antitussive and a sedative to suppress the cough and a mucolytic agent to help loosen thick sputum.

To relieve mucous membrane inflammation and dryness, humidify the air in the patient’s room, or instruct him to use a humidifier at home. Tell him to avoid using aerosols, powders, or other respiratory irritants — especially cigarettes. Make sure that the patient receives adequate fluids and

nutrition.

As indicated, prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as X-rays, a lung scan, bronchoscopy, and PFTs.

Patient Counseling

Explain how to use a respirator and humidifier and how to treat productive and nonproductive coughs. Teach the patient to avoid respiratory irritants. Explain the importance of adequate fluids and nutrition. If the patient smokes, stress the importance of smoking cessation, and refer him to appropriate resources and support groups to help him quit.

Pediatric Pointers

A nonproductive cough can be difficult to evaluate in infants and young children because it can’t be voluntarily induced and must be observed.

A sudden onset of paroxysmal nonproductive coughing may indicate aspiration of a foreign body

— a common danger in children, especially those between ages 6 months and 4 years. Nonproductive coughing can also result from several disorders that affect infants and children. With asthma, a characteristic nonproductive “tight” cough can arise suddenly or insidiously as an attack begins. The cough usually becomes productive toward the end of the attack. With bacterial pneumonia, a nonproductive, hacking cough arises suddenly and becomes productive in 2 to 3 days. Acute bronchiolitis has a peak incidence at age 6, with paroxysms of nonproductive coughing that become more frequent as the disease progresses. Acute otitis media, which is common in infants and young children because of their short eustachian tubes, also produces nonproductive coughing.

Typically, a child with measles has a slight, nonproductive, hacking cough that increases in severity. The earliest sign of cystic fibrosis may be a nonproductive, paroxysmal cough from retained secretions. Life-threatening pertussis produces a cough that becomes paroxysmal, with an inspiratory “whoop” or crowing sound. Airway hyperactivity causes a chronic nonproductive cough that increases with exercise or exposure to cold air. Psychogenic coughing may occur when the child is under stress, emotionally stimulated, or seeking attention.

Geriatric Pointers

Always ask elderly patients about nonproductive coughing because it may be an indication of serious acute or chronic illness.

REFERENCES

Baddley, J. W. , Winthrop, K. L., Patkar, N. M., et al. (2011). Geographic distribution of endemic fungal infections among older persons, United States. Emergency Infectious Disease, 17, 1664–1669.

McKinsey, D. S., & McKinsey, J. P. (2011). Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Seminar in Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 32, 735–744.

Cough, Productive

(See Also Cough, Barking and Cough, Nonproductive)

Productive coughing is the body’s mechanism for clearing airway passages of accumulated

secretions that normal mucociliary action doesn’t remove. It’s a sudden, forceful, noisy expulsion of air from the lungs that contains sputum, blood, or both. The sputum’s color, consistency, and odor provide important clues about the patient’s condition. A productive cough can occur as a single cough or as paroxysmal coughing, and it can be voluntarily induced, although it’s usually a reflexive response to stimulation of the airway mucosa.

Usually due to a cardiovascular or respiratory disorder, productive coughing commonly results from an acute or chronic infection that causes inflammation, edema, and increased mucus production in the airways. However, this sign can also result from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Inhalation of antigenic or irritating substances or foreign bodies can also cause a productive cough. In fact, the most common cause of chronic productive coughing is cigarette smoking, which produces mucoid sputum ranging in color from clear to yellow to brown.

Many patients minimize or overlook a chronic productive cough or accept it as normal. Such patients may not seek medical attention until an associated problem — such as dyspnea, hemoptysis, chest pain, weight loss, or recurrent respiratory tract infections — develops. The delay can have serious consequences because productive coughing is associated with several life-threatening disorders and can also herald airway occlusion from excessive secretions.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

A patient with a productive cough can develop acute respiratory distress from thick or excessive secretions, bronchospasm, or fatigue, so examine him before you take his history. Take his vital signs and check the rate, depth, and rhythm of respirations. Keep his airway patent, and be prepared to provide supplemental oxygen if he becomes restless or confused or if his respirations become shallow, irregular, rapid, or slow. Look for stridor, wheezing, choking, or gurgling. Be alert for nasal flaring and cyanosis, and retraction of intercostal muscles.

A productive cough may signal a severe life-threatening disorder. For example, coughing due to pulmonary edema produces thin, frothy, pink sputum, and coughing due to an asthma attack produces thick, mucoid sputum. Assist the patient to clear excess mucous with tracheal suctioning if necessary.

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, ask when the cough began, and find out how much sputum he’s coughing up each day. (The normal tracheobronchial tree can produce up to 3 oz [89 mL] of sputum per day.) At what time of day does he cough up the most sputum? Does his sputum production have any relationship to what or when he eats or to his activities or environment? Ask him if he has noticed an increase in sputum production since his coughing began. This may result from external stimuli or from such internal causes as chronic bronchial infection or a lung abscess. Also, ask about the color, odor, and consistency of the sputum. Blood-tinged or rust-colored sputum may result from trauma due to coughing or from an underlying condition, such as a pulmonary infection or a tumor. Foul-smelling sputum may result from an anaerobic infection, such as bronchitis or a lung abscess.

How does the cough sound? A hacking cough results from laryngeal involvement, whereas a “brassy” cough indicates major airway involvement. Does the patient feel pain associated with his productive cough? If so, ask about its location and severity and whether it radiates to other areas.

Does coughing, changing body position, or inspiration increase or help relieve his pain?

Next, ask the patient about his cigarette, drug, and alcohol use and whether his weight or appetite has changed. Find out if he has a history of asthma, allergies, or respiratory disorders, and ask about recent illnesses, surgery, or trauma. What medications is he taking? Does he work around chemicals or respiratory irritants such as silicone?

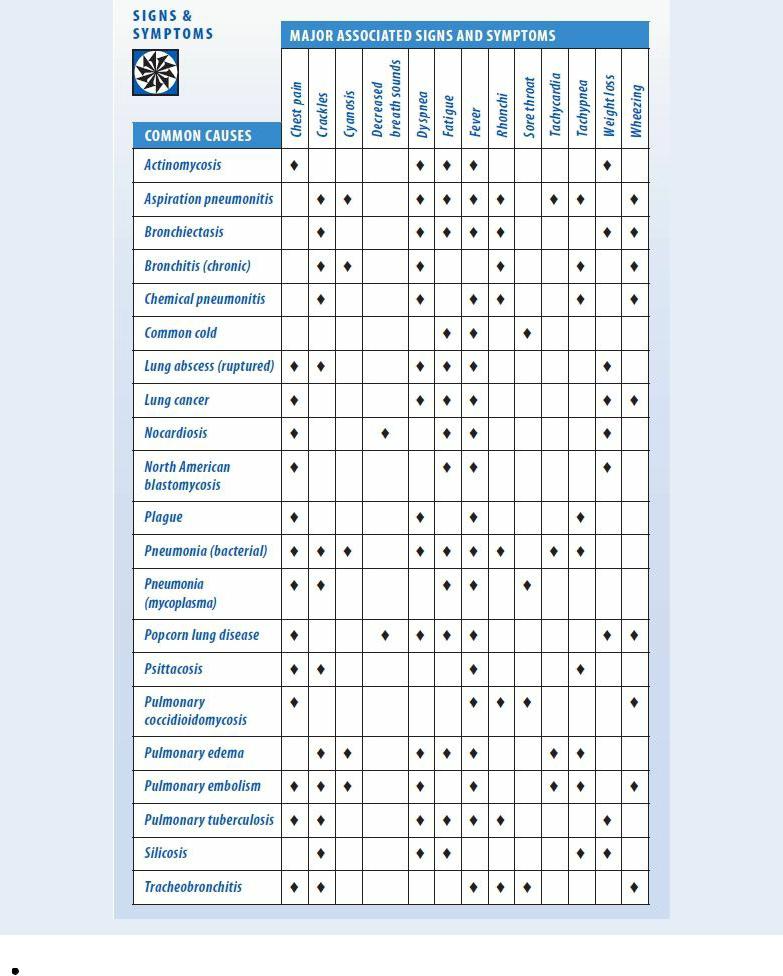

Examine the patient’s mouth and nose for congestion, drainage, or inflammation. Note his breath odor; halitosis can be a sign of pulmonary infection. Inspect his neck for distended veins, and palpate for tenderness and masses or enlarged lymph nodes. Observe his chest for accessory muscle use, retractions, and uneven chest expansion, and percuss for dullness, tympany, or flatness. Finally, auscultate for a pleural friction rub and abnormal breath sounds — rhonchi, crackles, or wheezes. (See Productive Cough: Common Causes and Associated Findings, page 196.)

Medical Causes

Actinomycosis. Actinomycosis begins with a cough that produces purulent sputum. A fever, weight loss, fatigue, weakness, dyspnea, night sweats, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis may also occur.

Aspiration pneumonitis. Aspiration pneumonitis causes coughing that produces pink, frothy and, possibly, purulent sputum. The patient also has marked dyspnea, a fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, wheezing, and cyanosis.

Bronchiectasis. The chronic cough of bronchiectasis produces copious, mucopurulent sputum that has characteristic layering (top, frothy; middle, clear; bottom, dense with purulent particles). The patient has halitosis; his sputum may smell foul or sickeningly sweet. Other characteristic findings include hemoptysis, persistent coarse crackles over the affected lung area, occasional wheezing, rhonchi, exertional dyspnea, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, weakness, a recurrent fever, and late-stage finger clubbing.

Bronchitis (chronic). Bronchitis causes a cough that may be nonproductive initially. Eventually, however, it produces mucoid sputum that becomes purulent. Secondary infection can also cause mucopurulent sputum, which may become blood tinged and foul smelling. The coughing, which may be paroxysmal during exercise, usually occurs when the patient is recumbent or rises from sleep.

The patient also exhibits prolonged expirations, increased use of accessory muscles for breathing, barrel chest, tachypnea, cyanosis, wheezing, exertional dyspnea, scattered rhonchi, coarse crackles (which can be precipitated by coughing), and late-stage clubbing.

Productive Cough: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Chemical pneumonitis. Chemical pneumonitis causes a cough with purulent sputum. It can also cause dyspnea, wheezing, orthopnea, a fever, malaise, and crackles; mucous membrane irritation of the conjunctivae, throat, and nose; laryngitis; or rhinitis. Signs and symptoms may increase for