Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

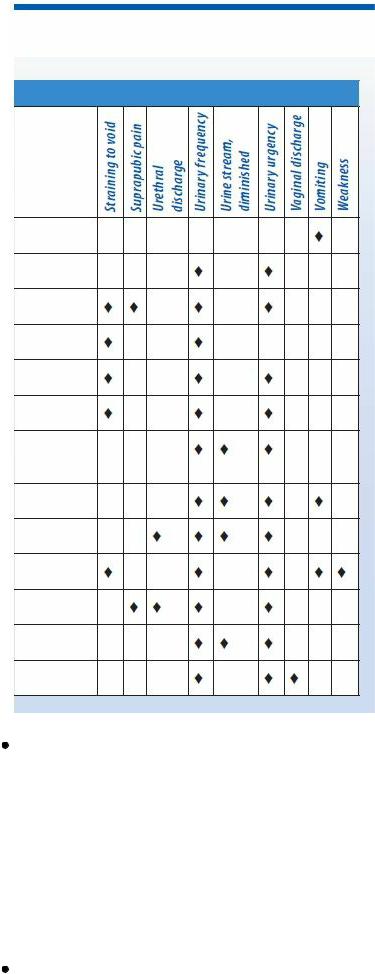

Bladder cancer. Bladder cancer, a predominantly male disorder, causes dysuria throughout voiding — a late symptom associated with urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, hematuria, and perineal, back, or flank pain.

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

Bladder cancer is relatively uncommon in Asians, Hispanics, and Native Americans. However, it’s twice as common in White males as in Black males.

Cystitis. Dysuria throughout voiding is common in all types of cystitis, as are urinary frequency, nocturia, straining to void, and hematuria. Bacterial cystitis, the most common cause of dysuria in women, may also produce urinary urgency, perineal and lower back pain, suprapubic

discomfort, fatigue and, possibly, a low-grade fever. With chronic interstitial cystitis, dysuria is accentuated at the end of voiding. In tubercular cystitis, symptoms may also include urinary urgency, flank pain, fatigue, and anorexia. With viral cystitis, severe dysuria occurs with gross hematuria, urinary urgency, and a fever.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Cystitis is more common in women than in men because women have a shorter urethra. For men, age is a factor. Men older than age 50 have a 15% higher risk of developing cystitis than younger men.

Paraurethral gland inflammation. Dysuria throughout voiding occurs with urinary frequency and urgency, a diminished urine stream, mild perineal pain and, occasionally, hematuria. Prostatitis. Acute prostatitis commonly causes dysuria throughout or toward the end of voiding as well as a diminished urine stream, urinary frequency and urgency, hematuria, suprapubic fullness, a fever, chills, fatigue, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. With chronic prostatitis, urethral narrowing causes dysuria throughout voiding. Related effects are urinary frequency and urgency; a diminished urine stream; perineal, back, and buttock pain; urethral discharge; nocturia; and, at times, hematospermia and ejaculatory pain.

Pyelonephritis (acute). More common in females, pyelonephritis causes dysuria throughout voiding. Other features include a persistent high fever with chills, costovertebral angle tenderness, unilateral or bilateral flank pain, weakness, urinary urgency and frequency, nocturia, straining on urination, and hematuria. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia may also occur.

Reiter’s syndrome. Reiter’s syndrome is a predominantly male disorder in which dysuria occurs 1 to 2 weeks after sexual contact. Initially, the patient has a mucopurulent discharge, urinary urgency and frequency, meatal swelling and redness, suprapubic pain, anorexia, weight loss, and a low-grade fever. Hematuria, conjunctivitis, arthritic symptoms, a papular rash, and oral and penile lesions may follow.

Urinary obstruction. Outflow obstruction by urethral strictures or calculi produces dysuria throughout voiding. (With complete obstruction, bladder distention develops and dysuria precedes voiding.) Other features are a diminished urine stream, urinary frequency and urgency, and a sensation of fullness or bloating in the lower abdomen or groin.

Vaginitis. Characteristically, dysuria occurs throughout voiding as urine touches inflamed or ulcerated labia. Other findings include urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, hematuria, perineal pain, and vaginal discharge and odor.

Other Causes

Chemical irritants. Dysuria may result from irritating substances, such as bubble bath salts and feminine deodorants; it’s usually most intense at the end of voiding. Spermicides may cause dysuria in both sexes. Other findings include urinary frequency and urgency, a diminished urine stream and, possibly, hematuria.

Drugs. Dysuria can result from monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Metyrosine can also cause transient dysuria.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s vital signs and intake and output. Administer prescribed drugs, and prepare the patient for such tests as urinalysis and cystoscopy.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of increased fluid intake and frequent urination. Teach the patient to perform proper perineal care. Discourage the use of bubble baths and vaginal deodorants. Discuss the importance of taking prescribed drugs as instructed.

Geriatric Pointers

Be aware that elderly patients tend to underreport their symptoms, even though older men have an increased incidence of nonsexually related UTIs and postmenopausal women have an increased incidence of noninfectious dysuria.

REFERENCES

Andrews, C., Aviles-Olmos, I., Hariz, M., & Foltynie, T. (2010). Which patients with dystonia benefit from deep brain stimulation? A metaregression of individual patient outcomes. Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgical Psychiatry, 81, 1383–1389.

Brighina, F., Romano, M., Giglia, G., Saia, V., Puma, A., Giglia, F., …Giglia, F. (2009). Effects of cerebellar TMS on motor cortex of patients with focal dystonia: A preliminary report. Experimental Brain Research, 192, 651–656.

E

Earache

[Otalgia]

Earaches usually result from disorders of the external and middle ear associated with infection, obstruction, or trauma. Their severity ranges from a feeling of fullness or blockage to deep, boring pain. At times, it may be difficult to determine the precise location of the earache. Earaches can be intermittent or continuous and may develop suddenly or gradually.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient to characterize his earache. How long has he had it? Is it intermittent or continuous? Is it painful or slightly annoying? Can he localize the site of ear pain? Does he have pain in other areas such as the jaw? Does he experience any associated hearing loss?

Ask about recent ear injury or other trauma. Does swimming or showering trigger ear discomfort? Is discomfort associated with itching? If so, find out where the itching is most intense and when it began. Ask about ear drainage and, if present, have the patient characterize it. Does he hear ringing, “swishing,” or other noise in his ears? Ask about dizziness or vertigo. Does it worsen when the patient changes position? Does he have difficulty swallowing, hoarseness, neck pain, or pain when he opens his mouth?

Find out if the patient has recently had a head cold or problems with his eyes, mouth, teeth, jaws, sinuses, or throat. Disorders in these areas may refer pain to the ear along the cranial nerves.

Find out if the patient has flown, been to a high-altitude location, or been scuba diving.

Begin your physical examination by inspecting the external ear for redness, drainage, swelling, or deformity. Then apply pressure to the mastoid process and tragus to elicit tenderness. Using an otoscope, examine the external auditory canal for lesions, bleeding or discharge, impacted cerumen, foreign bodies, tenderness, or swelling. Examine the tympanic membrane: Is it intact? Is it pearly gray (normal)? Look for tympanic membrane landmarks: the cone of light, umbo, pars tensa, and the handle and short process of the malleus. (See Using an Otoscope Correctly, page 276.) Perform the watch tick, whispered voice, Rinne, and Weber’s tests to assess for hearing loss.

Medical Causes

Abscess (extradural). Severe earache accompanied by a persistent ipsilateral headache, malaise, and a recurrent mild fever characterizes an abscess, which is a serious complication of middle ear infection.

Barotrauma (acute). Earache associated with barotrauma ranges from mild pressure to severe pain. Tympanic membrane ecchymosis or bleeding into the tympanic cavity may occur, producing a blue drumhead; the eardrum usually isn’t perforated.

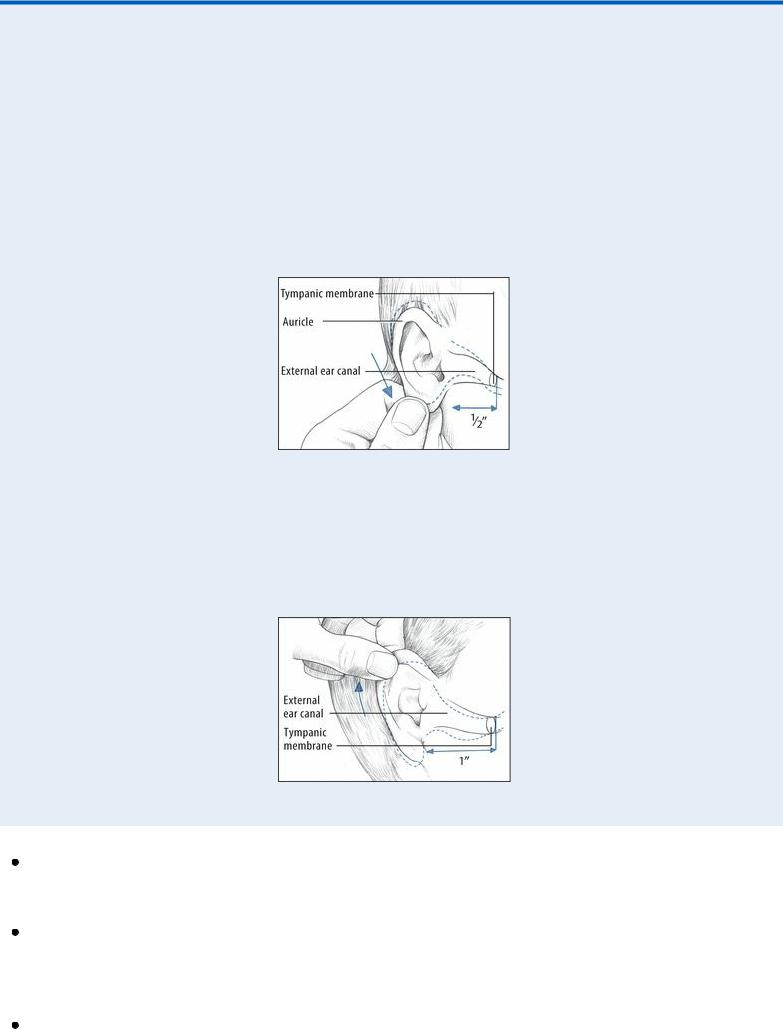

EXAMINATION TIP Using an Otoscope Correctly

EXAMINATION TIP Using an Otoscope Correctly

When the patient reports an earache, use an otoscope to inspect ear structures closely. Follow these techniques to obtain the best view and ensure patient safety.

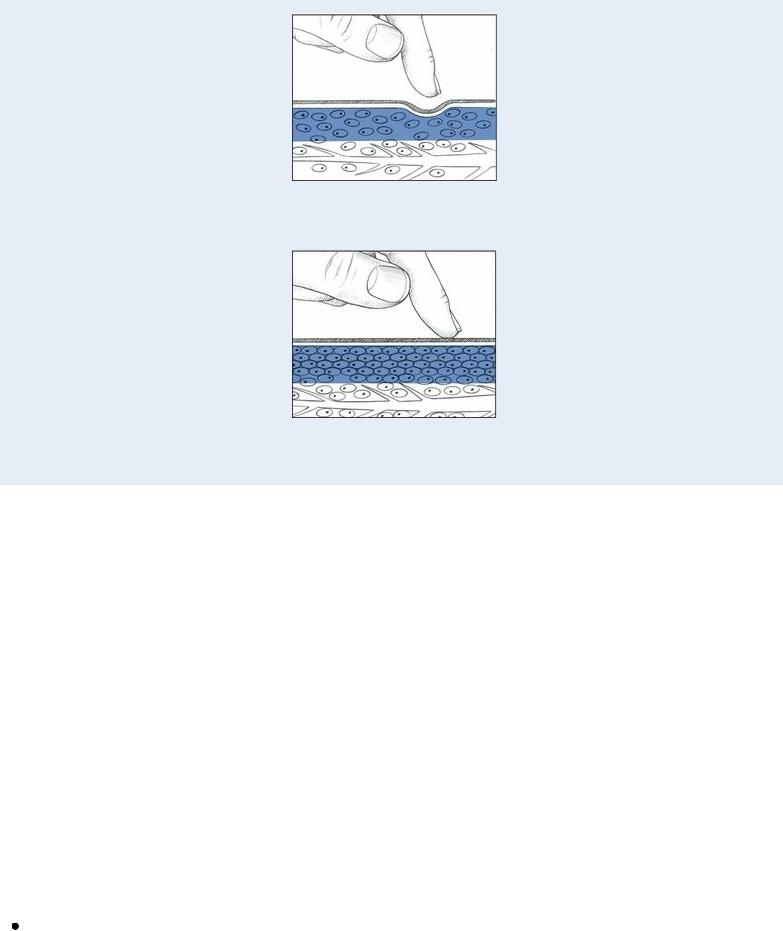

CHILD YOUNGER THAN AGE 3

To inspect an infant’s or a young child’s ear, grasp the lower part of the auricle and pull it down and back to straighten the upward S curve of the external canal. Then gently insert the speculum into the canal no more than ½” (1.2 cm).

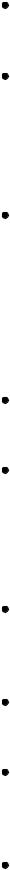

ADULT

To inspect an adult’s ear, grasp the upper part of the auricle and pull it up and back to straighten the external canal. Then insert the speculum about 1” (2.5 cm). Also, use this technique for children ages 3 and older.

Cerumen impaction. Impacted cerumen (earwax) may cause a sensation of vague pain, blockage, or fullness in the ear. Additional features include partial hearing loss, itching and, possibly, dizziness.

Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Herpes zoster oticus causes burning or stabbing ear pain, commonly associated with ear vesicles. The patient also complains of hearing loss and vertigo. Associated signs and symptoms include transitory, ipsilateral, facial paralysis; partial loss of taste; tongue vesicles; and nausea and vomiting.

Keratosis obturans. Mild ear pain is common with keratosis obturans, along with otorrhea and

tinnitus. Inspection reveals a white glistening plug obstructing the external meatus.

Mastoiditis (acute). Mastoiditis causes a dull ache and redness behind the ear accompanied by a fever that may suddenly increase. The eardrum appears dull and edematous and may perforate, and soft tissue near the eardrum may sag. A purulent discharge is seen in the external canal.

Ménière’s disease. Ménière’s disease is an inner ear disorder that can produce a sensation of fullness in the affected ear. Its classic effects, however, include severe vertigo, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss. The patient may also experience nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, and nystagmus.

Otitis externa. Earache characterizes acute and malignant otitis externa. Acute otitis externa begins with mild to moderate or intense ear pain that occurs with tragus manipulation. The pain may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, sticky yellow or purulent ear discharge, partial hearing loss, and a feeling of blockage. Later, ear pain intensifies, causing the entire side of the head to ache and throb. Fever may reach 104°F (40°C). Examination reveals swelling of the tragus, external meatus, and external canal; eardrum erythema; and lymphadenopathy. The patient also complains of dizziness and malaise.

Malignant otitis externa abruptly causes ear pain that’s aggravated by moving the auricle or tragus. The pain is accompanied by intense itching, purulent ear discharge, a fever, parotid gland swelling, and trismus. Examination reveals a swollen external canal with exposed cartilage and temporal bone. Cranial nerve palsy may occur.

Otitis media (acute). Otitis media is middle ear inflammation that may be serous or suppurative. Acute serous otitis media may cause a feeling of fullness in the ear, hearing loss, and a vague sensation of top-heaviness. The eardrum may be slightly retracted, amber, and marked by air bubbles and a meniscus, or it may be blue-black from hemorrhage.

Severe, deep, throbbing ear pain; hearing loss; and a fever that may reach 102°F (38.9°C) characterize acute suppurative otitis media. The pain increases steadily over several hours or days and may be aggravated by pressure on the mastoid antrum. Perforation of the eardrum is possible. Before rupture, the eardrum appears bulging and fiery red. Rupture causes purulent drainage and relieves the pain.

Chronic otitis media usually isn’t painful except during exacerbations. Persistent pain and discharge from the ear suggest osteomyelitis of the skull base or cancer.

Special Considerations

Administer an analgesic, and apply heat to relieve discomfort. Instill eardrops if necessary.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient or caregiver to instill eardrops correctly. Explain the importance of taking prescribed antibiotics correctly. Explain ways to avoid vertigo and ear trauma.

Pediatric Pointers

Common causes of earache in children are acute otitis media and the insertion of foreign bodies that become lodged or infected. Be alert for discharge from the opposite or both eyes and, in a young child, crying or ear tugging — nonverbal clues to earache.

To examine the child’s ears, place him in a supine position with his arms extended and held securely by his parent. Then hold the otoscope with the handle pointing toward the top of the child’s

head, and brace it against him using one or two fingers. Because an ear examination may upset the child with an earache, save it for the end of your physical examination.

REFERENCES

Brehm, J. M., Celedón, J. C., Soto-Quiros, M. E., Avila, L., Hunninghake, G. M., Forno E., … Litonjua, A. A. (2009). Serum vitamin D levels and markers of severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 179, 765–771.

Peters, B. S., dos Santos, L. C., Fisberg, M., Wood, R. J., & Martini, L. A. (2009). Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in Brazilian adolescents. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 54, 15–21.

Van Belle, T. L. , Gysemans, C., & Mathieu, C. (2011). Vitamin D in autoimmune, infectious and allergic diseases: A vital player? Best Practice Research in Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 25, 617–632.

Edema, Generalized

A common sign in severely ill patients, generalized edema is the excessive accumulation of interstitial fluid throughout the body. Its severity varies widely; slight edema may be difficult to detect, especially if the patient is obese, whereas massive edema is immediately apparent.

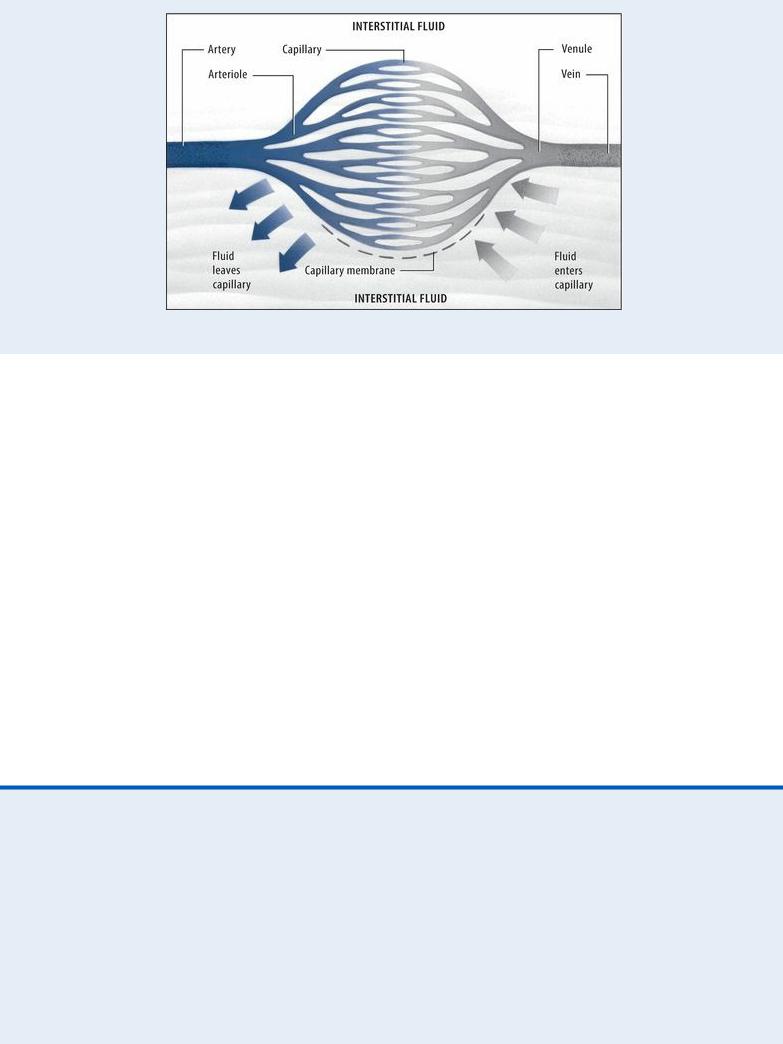

Understanding Fluid Balance

Normally, fluid moves freely between the interstitial and intravascular spaces to maintain homeostasis. Four basic pressures control fluid shifts across the capillary membrane that separates these spaces:

Capillary hydrostatic pressure (the internal fluid pressure on the capillary membrane) Interstitial fluid pressure (the external fluid pressure on the capillary membrane)

Osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration within the capillary)

Interstitial osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration outside the capillary)

Here’s how these pressures maintain homeostasis. Normally, capillary hydrostatic pressure is greater than plasma osmotic pressure at the capillary’s arterial end, forcing fluid out of the capillary. At the capillary’s venous end, the reverse is true: The plasma osmotic pressure is greater than the capillary hydrostatic pressure, drawing fluid into the capillary. Normally, the lymphatic system transports excess interstitial fluid back to the intravascular space.

Edema results when this balance is upset by increased capillary permeability, lymphatic obstruction, persistently increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, decreased plasma osmotic or interstitial fluid pressure, or dilation of precapillary sphincters.

Generalized edema is typically chronic and progressive. It may result from cardiac, renal, endocrine, lymphatic, or hepatic disorders as well as from severe burns, malnutrition, the effects of certain drugs and treatments, and after having a mastectomy.

Common factors responsible for edema are hypoalbuminemia and excess sodium ingestion or retention, both of which influence plasma osmotic pressure. (See Understanding Fluid Balance.) Cyclic edema associated with increased aldosterone secretion may occur in premenopausal women.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Quickly determine the location and severity of edema, including the degree of pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?) If the patient has severe edema, promptly take his vital signs, and check for jugular vein distention and cyanotic lips. Auscultate the lungs and heart. Be alert for signs of cardiac failure or pulmonary congestion, such as crackles, muffled heart sounds, or a ventricular gallop. Unless the patient is hypotensive, place him in Fowler’s position to promote lung expansion. Prepare to administer oxygen and an I.V. diuretic. Have emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

EXAMINATION TIP Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?

EXAMINATION TIP Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?

To differentiate pitting from nonpitting edema, press your finger against a swollen area for 5 seconds and then quickly remove it.

With pitting edema, pressure forces fluid into the underlying tissues, causing an indentation that slowly fills. To determine the severity of pitting edema, estimate the indentation’s depth in centimeters: 1+ (1 cm), 2+ (2 cm), 3+ (3 cm), or 4+ (4 cm).

With nonpitting edema, pressure leaves no indentation because fluid has coagulated in the tissues. Typically, the skin feels unusually tight and firm.

Pitting Edema (4+)

Nonpitting Edema

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a complete medical history. First, note when the edema began. Does it move throughout the course of the day — for example, from the upper extremities to the lower, periorbitally, or within the sacral area? Is the edema worse in the morning or at the end of the day? Is it affected by position changes? Is it accompanied by shortness of breath or pain in the arms or legs? Find out how much weight the patient has gained. Has his urine output changed in quantity or quality?

Next, ask about previous burns or cardiac, renal, hepatic, endocrine, or GI disorders. Have the patient describe his diet so you can determine whether he suffers from protein malnutrition. Explore his drug history, and note recent I.V. therapy.

Begin the physical examination by comparing the patient’s arms and legs for symmetrical edema. Also, note ecchymoses and cyanosis. Assess the back, sacrum, and hips of the bedridden patient for dependent edema. Palpate peripheral pulses, noting whether hands and feet feel cold. Finally, perform a complete cardiac and respiratory assessment.

Medical Causes

Angioneurotic edema or angioedema. Recurrent attacks of acute, painless, nonpitting edema involving the skin and mucous membranes — especially those of the respiratory tract, face, neck, lips, larynx, hands, feet, genitalia, or viscera — may be the result of a food or drug allergy or emotional stress, or they may be hereditary. Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea accompany visceral edema; dyspnea and stridor accompany life-threatening laryngeal edema.

Burns. Edema and associated tissue damage vary with the severity of the burn. Severe generalized edema (4+) may occur within 2 days of a major burn; localized edema may occur with a less severe burn.

Cirrhosis. Patients may display generalized edema of the body with a “puffy” appearance during the advanced stages of cirrhosis. As the disease progresses, healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue that ultimately leads to inadequate liver function. In addition, patients may also have edema in lower areas of the body, displayed in the legs and abdomen (ascites). Other symptoms include difficulty concentrating, sleeping problems, poor memory, jaundice, and dark-colored urine.

Heart failure. Severe, generalized pitting edema — occasionally anasarca — may follow leg edema late in this disorder. The edema may improve with exercise or elevation of the limbs and is typically worse at the end of the day. Among other classic late findings are hemoptysis, cyanosis, marked hepatomegaly, clubbing, crackles, and a ventricular gallop. Typically, the patient has tachypnea, palpitations, hypotension, weight gain despite anorexia, nausea, a slowed mental response, diaphoresis, and pallor. Dyspnea, orthopnea, tachycardia, and fatigue typify left-sided heart failure; jugular vein distention, enlarged liver, and peripheral edema typify rightsided heart failure.

Malnutrition. Anasarca in malnutrition may mask dramatic muscle wasting. Malnutrition also typically causes muscle weakness; lethargy; anorexia; diarrhea; apathy; dry, wrinkled skin; and signs of anemia, such as dizziness and pallor.

Myxedema. With myxedema, which is a severe form of hypothyroidism, generalized nonpitting edema is accompanied by dry, flaky, inelastic, waxy, pale skin; a puffy face; and an upper eyelid droop. Observation also reveals masklike facies, hair loss or coarsening, and psychomotor slowing. Associated findings include hoarseness, weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, bradycardia, hypoventilation, constipation, abdominal distention, menorrhagia, impotence, and infertility.

Nephrotic syndrome. Although nephrotic syndrome is characterized by generalized pitting edema, it’s initially localized around the eyes. With severe cases, anasarca develops, increasing body weight by up to 50%. Other common signs and symptoms are ascites, anorexia, fatigue, malaise, depression, and pallor.

Pericardial effusion. With pericardial effusion, generalized pitting edema may be most prominent in the arms and legs. It may be accompanied by chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, a nonproductive cough, a pericardial friction rub, jugular vein distention, dysphagia, and a fever.

Pericarditis (chronic constructive). Resembling right-sided heart failure, pericarditis usually begins with pitting edema of the arms and legs that may progress to generalized edema. Other signs and symptoms include ascites, Kussmaul’s sign, dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, abdominal distention, and hepatomegaly.

Renal failure. With acute renal failure, generalized pitting edema occurs as a late sign. With chronic renal failure, edema is less likely to become generalized; its severity depends on the degree of fluid overload. Both forms of renal failure cause oliguria, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, hypertension, dyspnea, crackles, dizziness, and pallor.

Other Causes