Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

symptoms may include left lower quadrant pain that’s relieved by defecation, alternating episodes of constipation and diarrhea, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, rebound tenderness, and a distended tympanic abdomen.

Dysentery. Bloody diarrhea is common in infection with Shigella, Amoeba, and Campylobacter, but rare with Salmonella. Abdominal pain or cramps, tenesmus, a fever, and nausea may also occur.

Esophageal varices (ruptured). In esophageal varices, a lifethreatening disorder, hematochezia may range from slight rectal oozing to grossly bloody stools and may be accompanied by mild to severe hematemesis or melena. This painless but massive hemorrhage may precipitate signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. In fact, signs of shock occasionally precede overt signs of bleeding. Typically, the patient has a history of chronic liver disease.

Food poisoning (staphylococcal). The patient may have bloody diarrhea 1 to 6 hours after ingesting food toxins. Accompanying signs and symptoms include severe, cramping abdominal pain; nausea and vomiting; and prostration, all of which last a few hours.

Hemorrhoids. Hematochezia may accompany external hemorrhoids, which typically cause painful defecation, resulting in constipation. Less painful internal hemorrhoids usually produce more chronic bleeding with bowel movements, which may eventually lead to signs of anemia, such as weakness and fatigue.

Leptospirosis. The severe form of leptospirosis — Weil’s syndrome — produces hematochezia or melena along with other signs of bleeding, such as epistaxis and hemoptysis. The bleeding is typically preceded by a sudden frontal headache and severe thigh and lumbar myalgia that may be accompanied by cutaneous hyperesthesia. Conjunctival suffusion is indicative. Bleeding is followed by chills, a rapidly rising fever and, perhaps, nausea and vomiting. A fever, a headache, and myalgia usually intensify and persist for weeks. Other findings may include right upper quadrant tenderness, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.

Peptic ulcer. Upper GI bleeding is a common complication in peptic ulcer. The patient may display hematochezia, hematemesis, or melena, depending on the rapidity and amount of bleeding. If the peptic ulcer penetrates an artery or vein, massive bleeding may precipitate signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia. Other findings may include chills, a fever, nausea and vomiting, and signs of dehydration, such as dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, and thirst. The patient typically has a history of epigastric pain that’s relieved by foods or antacids; he may also have a history of habitually using tobacco, alcohol, or NSAIDs.

Ulcerative proctitis. Ulcerative proctitis typically causes an intense urge to defecate, but the patient passes only bright red blood, pus, or mucus. Other common signs and symptoms include acute constipation and tenesmus.

Other Causes

Tests. Certain procedures, especially colonoscopy, polypectomy, and proctosigmoidoscopy, may cause rectal bleeding. Bowel perforation is rare.

Special Considerations

Place the patient on bed rest and check his vital signs frequently, watching for signs of shock, such as

hypotension, tachycardia, a weak pulse, and tachypnea. Monitor his intake and output hourly. Remember to provide emotional support because hematochezia may frighten the patient.

Prepare the patient for blood tests and GI procedures, such as endoscopy and GI X-rays. Visually examine the patient’s stools and test them for occult blood. If necessary, send a stool sample to the laboratory to check for parasites.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms the patient should report. Teach the patient about ostomy self-care and discuss proper bowel elimination habits. Explain dietary recommendations and restrictions.

Pediatric Pointers

Hematochezia is much less common in children than in adults. It may result from structural disorders, such as intussusception and Meckel’s diverticulum, and from inflammatory disorders, such as peptic ulcer disease and ulcerative colitis.

In children, ulcerative colitis typically produces chronic, rather than acute, signs and symptoms and may also cause slow growth and maturation related to malnutrition. Suspect sexual abuse in all cases of rectal bleeding in children.

Geriatric Pointers

Because older people have an increased risk of colon cancer, hematochezia should be evaluated with colonoscopy after perirectal lesions have been ruled out as the cause of bleeding.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of colorectal cancer screening among adults—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 51–56.

Zapka, J., Klabunde, C. N., Taplin, S., Yuan, G., Ransohoff, D., & Kobrin, S. (2012). Screening colonoscopy in the US: Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27, 1150–1158.

Hematuria

A cardinal sign of renal and urinary tract disorders, hematuria is the abnormal presence of blood in urine. Strictly defined, it means three or more red blood cells (RBCs) per high-power microscopic field in urine. Microscopic hematuria is confirmed by an occult blood test, whereas macroscopic hematuria is immediately visible. However, macroscopic hematuria must be distinguished from pseudohematuria. (See Confirming Hematuria.) Macroscopic hematuria may be continuous or intermittent, is commonly accompanied by pain, and may be aggravated by prolonged standing or walking.

Confirming Hematuria

If the patient’s urine appears blood tinged, be sure to rule out pseudohematuria, red or pink urine caused by urinary pigments. First, carefully observe the urine specimen. If it contains red sediment, it’s probably true hematuria.

Then check the patient’s history for the use of drugs associated with pseudohematuria, including rifampin, chlorzoxazone, phenazopyridine, phenothiazines, doxorubicin, phensuximide, phenytoin, daunomycin, and laxatives with phenolphthalein.

Ask about the patient’s intake of beets, berries, or foods with red dyes that may color the urine red. Be aware that porphyrinuria and excess urate excretion can also cause pseudohematuria.

Finally, test the urine using a chemical reagent strip. This test can confirm even microscopic hematuria and can also estimate the amount of blood present.

Hematuria may be classified by the stage of urination it predominantly affects. Bleeding at the start of urination — initial hematuria — usually indicates urethral pathology; bleeding at the end of urination

— terminal hematuria — usually indicates pathology of the bladder neck, posterior urethra, or prostate; bleeding throughout urination — total hematuria — usually indicates pathology above the bladder neck.

Hematuria may result from one of two mechanisms: rupture or perforation of vessels in the renal system or urinary tract, or impaired glomerular filtration, which allows RBCs to seep into the urine. The color of the bloody urine provides a clue to the source of the bleeding. Generally, dark or brownish blood indicates renal or upper urinary tract bleeding, whereas bright red blood indicates lower urinary tract bleeding.

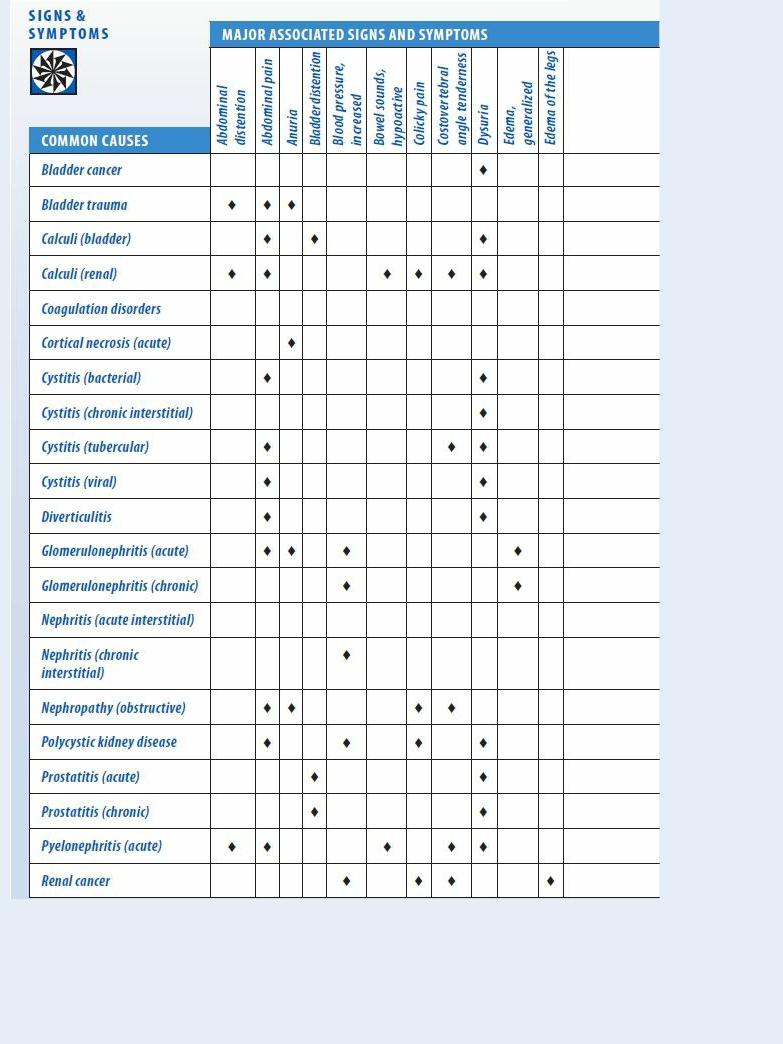

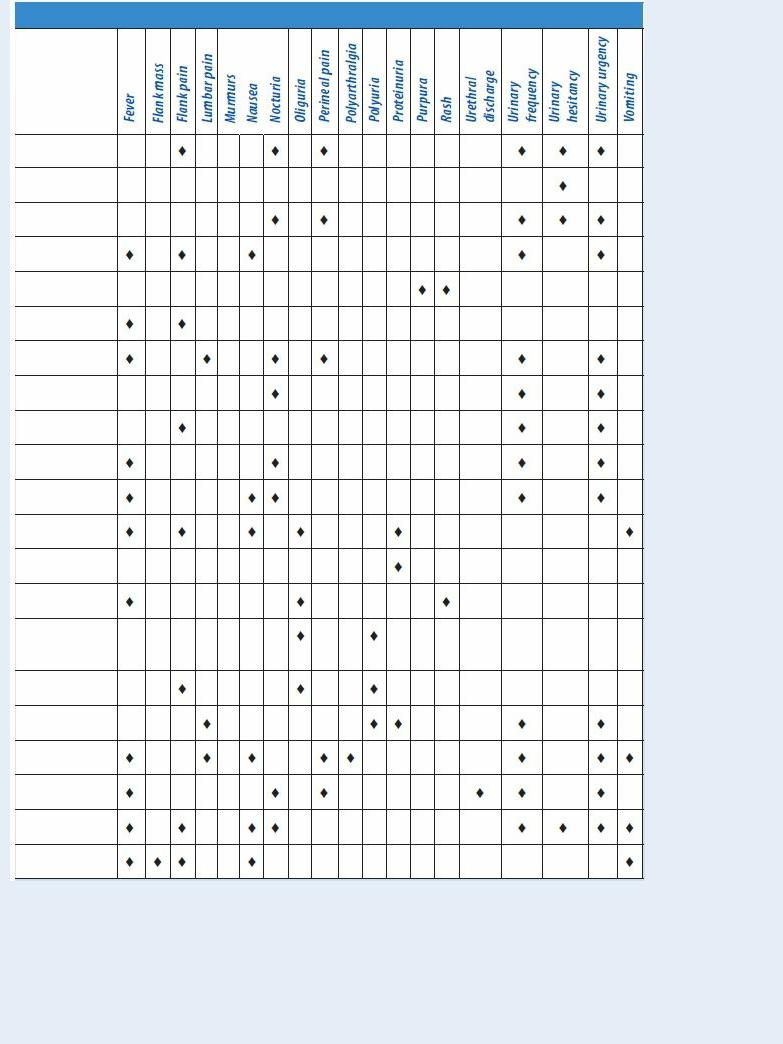

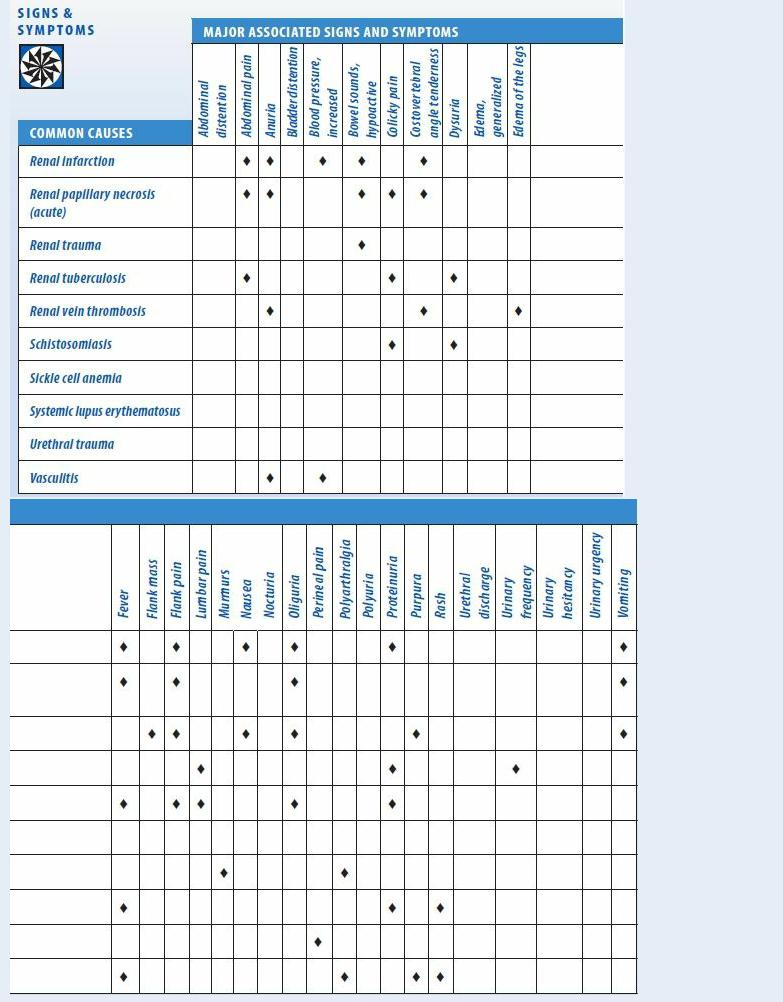

Although hematuria usually results from renal and urinary tract disorders, it may also result from certain GI, prostate, vaginal, or coagulation disorders or from the effects of certain drugs. Invasive therapy and diagnostic tests that involve manipulative instrumentation of the renal and urologic systems may also cause hematuria. Nonpathologic hematuria may result from fever and hypercatabolic states. Transient hematuria may follow strenuous exercise. (See Hematuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 386 to 389.)

History and Physical Examination

After detecting hematuria, take a pertinent health history. If hematuria is macroscopic, ask the patient when he first noticed blood in his urine. Does it vary in severity between voidings? Is it worse at the beginning, middle, or end of urination? Has it occurred before? Is the patient passing clots? To rule out artifactitious hematuria, ask about bleeding hemorrhoids or the onset of menses, if appropriate. Ask if there’s pain or burning with hematuria episodes.

Ask about recent abdominal or flank trauma. Has the patient been exercising strenuously? Note a history of renal, urinary, prostatic, or coagulation disorders. Then obtain a drug history, noting anticoagulants or aspirin.

Begin the physical examination by palpating and percussing the abdomen and flanks. Next, percuss the costovertebral angle (CVA) to elicit tenderness. Check the urinary meatus for bleeding or other abnormalities. Using a chemical reagent strip, test a urine specimen for protein. A vaginal or digital rectal examination may be necessary.

Medical Causes

Bladder cancer. A primary cause of gross hematuria in men, bladder cancer may also produce pain in the bladder, rectum, pelvis, flank, back, or leg. Other common features are nocturia,

dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, vomiting, diarrhea, and insomnia.

Bladder trauma. Gross hematuria is characteristic in traumatic rupture or perforation of the bladder. Typically, hematuria is accompanied by lower abdominal pain and, occasionally, anuria despite a strong urge to void. The patient may also develop swelling of the scrotum, buttocks, or perineum and signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension.

Calculi. Bladder and renal calculi produce hematuria, which may be associated with signs of a urinary tract infection (UTI), such as dysuria and urinary frequency and urgency. Bladder calculi usually cause gross hematuria, referred pain to the lower back or penile or vulvar area and, in some patients, bladder distention.

Renal calculi may produce microscopic or gross hematuria. The cardinal symptom, however, is colicky pain that travels from the CVA to the flank, suprapubic region, and external genitalia when a calculus is passed. The pain may be excruciating at its peak. Other signs and symptoms may include nausea and vomiting, restlessness, a fever, chills, abdominal distention and, possibly, decreased bowel sounds.

Coagulation disorders. Macroscopic hematuria may be present in coagulation disorders, such as thrombocytopenia or disseminated intravascular coagulation. Other features include epistaxis, purpura (petechiae and ecchymoses), and signs of GI bleeding.

Hematuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Cortical necrosis (acute). Accompanying gross hematuria in acute cortical necrosis are intense flank pain, anuria, leukocytosis, and a fever.

Cystitis. Hematuria is a telling sign in all types of cystitis. Bacterial cystitis usually produces macroscopic hematuria with urinary urgency and frequency, dysuria, nocturia, and tenesmus. The patient complains of perineal and lumbar pain, suprapubic discomfort, and fatigue and occasionally has a low-grade fever.

More common in women, chronic interstitial cystitis occasionally causes grossly bloody hematuria. Associated features include urinary frequency, dysuria, nocturia, and tenesmus. Microscopic and macroscopic hematuria may occur with tubercular cystitis, which may also cause urinary urgency and frequency, dysuria, tenesmus, flank pain, fatigue, and anorexia. Viral cystitis usually produces hematuria, urinary urgency and frequency, dysuria, nocturia, tenesmus, and a fever.

Diverticulitis. When diverticulitis involves the bladder, it usually causes microscopic hematuria, urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, and nocturia. Characteristic findings include left lower quadrant pain, abdominal tenderness, constipation or diarrhea and, at times, a palpable, firm, fixed, and tender abdominal mass. The patient may also develop mild nausea, flatulence, and a low-grade fever.

Glomerulonephritis. Acute glomerulonephritis usually begins with gross hematuria that tapers off to microscopic hematuria and red cell casts, which may persist for months. It may also produce oliguria or anuria, proteinuria, a mild fever, fatigue, flank and abdominal pain, generalized edema, increased blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, and signs of lung congestion, such as crackles and a productive cough.

Chronic glomerulonephritis usually causes microscopic hematuria accompanied by proteinuria, generalized edema, and increased blood pressure. Signs and symptoms of uremia may also occur in advanced disease.

Nephritis (interstitial). Typically, nephritis causes microscopic hematuria. However, the patient with acute interstitial nephritis may develop gross hematuria. Other findings are a fever, a maculopapular rash, and oliguria or anuria. In chronic interstitial nephritis, the patient has dilute — almost colorless — urine that may be accompanied by polyuria and increased blood pressure.

Nephropathy (obstructive). Obstructive nephropathy may cause microscopic or macroscopic hematuria, but urine is rarely grossly bloody. The patient may report colicky flank and abdominal pain, CVA tenderness, and anuria or oliguria that alternates with polyuria.

Polycystic kidney disease. Polycystic kidney disease is a hereditary disorder that may cause recurrent microscopic or gross hematuria. Although commonly asymptomatic before age 40, it may cause increased blood pressure, polyuria, dull flank pain, and signs of a UTI, such as dysuria and urinary frequency and urgency. Later, the patient develops a swollen, tender abdomen and lumbar pain that’s aggravated by exertion and relieved by lying down. He may also have proteinuria and colicky abdominal pain from the ureteral passage of clots or stones.

Prostatitis. Whether acute or chronic, prostatitis may cause macroscopic hematuria, usually at the end of urination. It may also produce urinary frequency and urgency and dysuria followed by visible bladder distention.

Acute prostatitis also produces fatigue, malaise, myalgia, polyarthralgia, a fever with chills, nausea, vomiting, perineal and low back pain, and a decreased libido. Rectal palpation reveals

a tender, swollen, boggy, firm prostate.

Chronic prostatitis commonly follows an acute attack. It may cause persistent urethral discharge, dull perineal pain, ejaculatory pain, and a decreased libido.

Pyelonephritis (acute). Acute pyelonephritis typically produces microscopic or macroscopic hematuria that progresses to grossly bloody hematuria. After the infection resolves, microscopic hematuria may persist for a few months. Related signs and symptoms include a persistent high fever, unilateral or bilateral flank pain, CVA tenderness, shaking chills, weakness, fatigue, dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, and tenesmus. The patient may also exhibit nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and signs of paralytic ileus, such as hypoactive or absent bowel sounds and abdominal distention.

Renal cancer. Common symptoms include grossly bloody hematuria, persistent pain in the side, and a lump or mass in the side or the abdomen. Colicky pain may accompany the passage of clots. Other findings include a fever, CVA tenderness, and increased blood pressure. In advanced disease, the patient may develop weight loss and nausea and vomiting.

Renal infarction. Typically, renal infarction produces gross hematuria. The patient may complain of constant, severe flank and upper abdominal pain accompanied by CVA tenderness, anorexia, and nausea and vomiting. Other findings include oliguria or anuria, proteinuria, hypoactive bowel sounds and, a day or two after infarction, a fever and increased blood pressure.

Renal papillary necrosis (acute). Acute renal papillary necrosis usually produces grossly bloody hematuria, which may be accompanied by intense flank pain, CVA tenderness, abdominal rigidity and colicky pain, oliguria or anuria, pyuria, fever, chills, vomiting, and hypoactive bowel sounds. Arthralgia and hypertension are common.

Renal trauma. About 80% of patients with renal trauma have microscopic or gross hematuria. Accompanying signs and symptoms may include flank pain, a palpable flank mass, oliguria, hematoma or ecchymoses over the upper abdomen or flank, nausea and vomiting, and hypoactive bowel sounds. Severe trauma may precipitate signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension.

Renal tuberculosis. Gross hematuria is commonly the first sign of renal tuberculosis. It may be accompanied by urinary frequency, dysuria, pyuria, tenesmus, colicky abdominal pain, lumbar pain, and proteinuria.

Renal vein thrombosis. Grossly bloody hematuria usually occurs in renal vein thrombosis. In abrupt venous obstruction, the patient experiences severe flank and lumbar pain as well as epigastric and CVA tenderness. Other features include a fever, pallor, proteinuria, peripheral edema and, when the obstruction is bilateral, oliguria or anuria and other uremic signs. The kidneys are easily palpable. Gradual venous obstruction causes signs of nephrotic syndrome, proteinuria and, occasionally, peripheral edema.

Schistosomiasis. Schistosomiasis usually causes intermittent hematuria at the end of urination. It may be accompanied by dysuria, colicky renal and bladder pain, and palpable lower abdominal masses.

Sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is a hereditary disorder in which gross hematuria may result from congestion of the renal papillae. Associated signs and symptoms may include pallor, dehydration, chronic fatigue, polyarthralgia, leg ulcers, dyspnea, chest pain, impaired growth and development, hepatomegaly and, possibly, jaundice. Auscultation reveals tachycardia and systolic and diastolic murmurs.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Gross hematuria and proteinuria may occur when SLE involves the kidneys. Cardinal associated features include nondeforming joint pain and stiffness, a butterfly rash, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, seizures or psychoses, a recurrent fever, lymphadenopathy, oral or nasopharyngeal ulcers, anorexia, and weight loss.

Urethral trauma. Initial hematuria may occur, possibly with blood at the urinary meatus, local pain, and penile or vulvar ecchymoses.

Vasculitis. Hematuria is usually microscopic in vasculitis. Associated signs and symptoms include malaise, myalgia, polyarthralgia, a fever, increased blood pressure, pallor and, occasionally, anuria. Other features, such as urticaria and purpura, may reflect the etiology of vasculitis.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Renal biopsy is the diagnostic test most commonly associated with hematuria. This sign may also result from biopsy or manipulative instrumentation of the urinary tract such as in cystoscopy.

Drugs. Drugs that commonly cause hematuria are anticoagulants, aspirin (toxicity), analgesics, cyclophosphamide, metyrosine, phenylbutazone, oxyphenbutazone, penicillin, rifampin, and thiabendazole.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

When taken with an anticoagulant, herbal remedies, such as garlic and Ginkgo biloba, can cause adverse reactions, including excessive bleeding and hematuria.

Treatments. Any therapy that involves manipulative instrumentation of the urinary tract, such as transurethral prostatectomy, may cause microscopic or macroscopic hematuria. Following a kidney transplant, a patient may experience hematuria with or without clots, which may require indwelling urinary catheter irrigation.

Special Considerations

Because hematuria may frighten and upset the patient, be sure to provide emotional support. Check his vital signs at least every 4 hours and monitor intake and output, including the amount and pattern of hematuria. If the patient has an indwelling urinary catheter in place, ensure its patency and irrigate it if necessary to remove clots and tissue that may impede urine drainage. Administer prescribed analgesics, and enforce bed rest as indicated. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood and urine studies, cystoscopy, and renal X-rays or biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in three-glass technique for collecting serial urine specimens. Emphasize the need for increasing his fluid intake.

Pediatric Pointers