Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

lymph nodes near the site of the flea bite. Septicemic plague develops as a fulminant illness generally with the bubonic form. The pneumonic form may be contracted from person to person through direct contact via the respiratory system or through biological warfare from aerosolization and inhalation of the organism. The onset is usually sudden with chills, a fever, a headache, and myalgia. Pulmonary signs and symptoms include a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

Pleurisy. The chest pain of pleurisy arises abruptly and reaches maximum intensity within a few hours. The pain is sharp, even knifelike, usually unilateral, and located in the lower and lateral aspects of the chest. Deep breathing, coughing, or thoracic movement characteristically aggravates it. Auscultation over the painful area may reveal decreased breath sounds, inspiratory crackles, and a pleural friction rub. Dyspnea; rapid, shallow breathing; cyanosis; a fever; and fatigue may also occur.

Pneumonia. Pneumonia produces pleuritic chest pain that increases with deep inspiration and is accompanied by shaking chills and fever. The patient has a dry cough that later becomes productive. Other signs and symptoms include crackles, rhonchi, tachycardia, tachypnea, myalgia, fatigue, a headache, dyspnea, abdominal pain, anorexia, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and diaphoresis.

Pneumothorax. Spontaneous pneumothorax, a life-threatening disorder, causes sudden sharp chest pain that’s severe, typically unilateral, and rarely localized; it increases with chest movement. When the pain is centrally located and radiates to the neck, it may mimic that of an MI. After the pain’s onset, dyspnea and cyanosis progressively worsen. Breath sounds are decreased or absent on the affected side with hyperresonance or tympany, subcutaneous crepitation, and decreased vocal fremitus. Asymmetrical chest expansion, accessory muscle use, a nonproductive cough, tachypnea, tachycardia, anxiety, and restlessness also occur.

Pulmonary embolism. A pulmonary embolism is a blockage of an artery in the lungs typically caused by a deep vein thrombus that produces chest pain or a choking sensation. Typically, the patient first experiences sudden dyspnea with intense angina-like or pleuritic pain aggravated by deep breathing and thoracic movement. Other findings include tachycardia, tachypnea, a cough (nonproductive or producing blood-tinged sputum), a low-grade fever, restlessness, diaphoresis, crackles, a pleural friction rub, diffuse wheezing, dullness to percussion, signs of circulatory collapse (a weak, rapid pulse; hypotension), paradoxical pulse, signs of cerebral ischemia (transient unconsciousness, coma, seizures), signs of hypoxia (restlessness) and, particularly in the elderly, hemiplegia and other focal neurologic deficits. Less common signs include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, and leg edema. A patient with a large embolus may have cyanosis and jugular vein distention.

Q fever. Q fever is a rickettsial disease caused by Coxiella burnetii. The primary source of human infection results from exposure to infected animals. Cattle, sheep, and goats are most likely to carry the organism. Human infection results from exposure to contaminated milk, urine, feces, or other fluids from infected animals. Infection may also result from inhaling contaminated barnyard dust. C. burnetii is highly infectious and is considered a possible airborne agent for biological warfare. Signs and symptoms include a fever, chills, a severe headache, malaise, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The fever may last up to 2 weeks. In severe cases, the patient may develop hepatitis or pneumonia.

Sickle cell crisis. Chest pain associated with sickle cell crisis typically has a bizarre

distribution. It may start as a vague pain, commonly located in the back, hands, or feet. As the pain worsens, it becomes generalized or localized to the abdomen or chest, causing severe pleuritic pain. The presence of chest pain and difficulty breathing requires prompt intervention. The patient may also have abdominal distention and rigidity, dyspnea, a fever, and jaundice.

Thoracic outlet syndrome. Commonly causing paresthesia along the ulnar distribution of the arm, thoracic outlet syndrome can be confused with angina, especially when it affects the left arm. The patient usually experiences angina-like pain after lifting his arms above his head, working with his hands above his shoulders, or lifting a weight. The pain disappears as soon as he lowers his arms. Other signs and symptoms include pale skin and a difference in blood pressure between both arms.

Tuberculosis (TB). In a patient with TB, pleuritic chest pain and fine crackles occur after coughing. Associated signs and symptoms include night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, a fever, malaise, dyspnea, easy fatigability, a mild to severe productive cough, occasional hemoptysis, dullness to percussion, increased tactile fremitus, and amphoric breath sounds.

Tularemia. Also known as rabbit fever, tularemia is an infectious disease that’s caused by the gram-negative, non–spore-forming bacterium Francisella tularensis. It’s typically a rural disease found in wild animals, water, and moist soil. It’s transmitted to humans through a bite by an infected insect or tick, handling infected animal carcasses, drinking contaminated water, or inhaling the bacteria. It’s considered a possible airborne agent for biological warfare. Signs and symptoms following inhalation of the organism include the abrupt onset of a fever, chills, a headache, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Other Causes

Chinese restaurant syndrome (CRS). CRS is a benign condition — a reaction to excessive ingestion of monosodium glutamate, a common additive in Chinese foods — that mimics the signs of an acute MI. The patient may complain of retrosternal burning, ache, or pressure; a burning sensation over his arms, legs, and face; a sensation of facial pressure; a headache; shortness of breath; and tachycardia.

Drugs. The abrupt withdrawal of a beta-adrenergic blocker can cause rebound angina if the patient has coronary heart disease — especially if he has received high doses for a prolonged period.

Special Considerations

As needed, prepare the patient for cardiopulmonary studies, such as an electrocardiogram and a lung scan. Collect a serum sample for cardiac enzyme and electrolyte levels. Explain the purpose and procedure of each diagnostic test to the patient to help alleviate his anxiety. Also, explain the purpose of any prescribed drugs, and make sure that the patient understands the dosage, schedule, and possible adverse effects.

Keep in mind that a patient with chest pain may deny his discomfort, so stress the importance of reporting symptoms to allow adjustment of his treatment.

Patient Counseling

Alert the patient or caregiver to signs and symptoms that require medical attention. Explain the diagnostic tests needed. Provide instructions about any prescribed drugs.

Pediatric Pointers

Even a child old enough to talk may have difficulty describing chest pain, so be alert for nonverbal clues, such as restlessness, facial grimaces, or holding of the painful area. Ask the child to point to the painful area and then to where the pain goes (to find out if it’s radiating). Determine the pain’s severity by asking the parents if the pain interferes with the child’s normal activities and behavior. Remember, a child may complain of chest pain in an attempt to get attention or to avoid attending school.

Geriatric Pointers

Because older patients have a higher risk of developing lifethreatening conditions (such as an MI, angina, and aortic dissection), you must carefully evaluate chest pain in these patients.

REFERENCES

Hoffmann, U., Truong, Q. A., Schoenfeld, D. A., Chou, E. T., Woodard, P. K., Nagurney, J. T., … Udelson, J. E.; for the ROMICAT-II Investigators. (2012). Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(4), 299–308.

Miller, C. D., Hwang, W., Hoekstra, J. W., Case, D., Lefebvre, C., & Blumstein, H. (2010). Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with observation unit care reduces cost for patients with emergent chest pain: A randomized trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 56(3), 209–219.

Cheyne-Stokes Respirations

The most common pattern of periodic breathing, Cheyne-Stokes respirations are characterized by a waxing and waning period of hyperpnea that alternates with a shorter period of apnea. This pattern can occur normally in patients with heart or lung disease. It usually indicates increased intracranial pressure (ICP) from a deep cerebral or brain stem lesion or a metabolic disturbance in the brain.

Cheyne-Stokes respirations may indicate a major change in the patient’s condition — usually a deterioration. For example, in a patient who has had head trauma or brain surgery, Cheyne-Stokes respirations may signal increasing ICP. Cheyne-Stokes respirations can occur normally in a patient who lives at high altitudes.

Time the periods of hyperpnea and apnea for 3 to 4 minutes to evaluate respirations and to obtain baseline data. Be alert for prolonged periods of apnea. Frequently check the patient’s blood pressure; also check his skin color to detect signs of hypoxemia. Maintain airway patency and administer oxygen as needed. If the patient’s condition worsens, endotracheal intubation is necessary.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect Cheyne-Stokes respirations in a patient with a history of head trauma, recent brain surgery, or another brain insult, quickly take his vital signs. Keep his head elevated 30 degrees, and perform a rapid neurologic examination to obtain baseline data. Reevaluate the patient’s neurologic status frequently. If ICP continues to rise, you’ll detect changes in the

patient’s level of consciousness (LOC), pupillary reactions, and ability to move his extremities. ICP monitoring is indicated.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, obtain a brief history. Ask especially about drug use.

Medical Causes

Heart failure. With left-sided heart failure, Cheyne-Stokes respirations may occur with exertional dyspnea and orthopnea. Related findings include fatigue, weakness, tachycardia, tachypnea, and crackles. The patient may also have a cough, generally nonproductive but occasionally producing clear or blood-tinged sputum.

Hypertensive encephalopathy. Hypertensive encephalopathy is a life-threatening disorder in which severe hypertension precedes Cheyne-Stokes respirations. The patient’s LOC is decreased, and he may experience vomiting, seizures, severe headaches, papilledema vision disturbances (including transient blindness), or transient paralysis.

Increased ICP. As ICP rises, Cheyne-Stokes respirations are the first irregular respiratory pattern to occur. It’s preceded by a decreased LOC and accompanied by hypertension, headache, vomiting, impaired or unequal motor movement, and vision disturbances (blurring, diplopia, photophobia, and pupillary changes). In late stages of increased ICP, bradycardia and a widened pulse pressure occur.

Renal failure. With end-stage chronic renal failure, Cheyne-Stokes respirations may occur in addition to bleeding gums, oral lesions, ammonia breath odor, and marked changes in every body system.

Other Causes

Drugs. Large doses of an opioid, a hypnotic, or a barbiturate can precipitate Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

Special Considerations

When evaluating Cheyne-Stokes respirations, be careful not to mistake periods of hypoventilation or decreased tidal volume for complete apnea.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient and a responsible person to recognize the difference between sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations. Explain the causes and treatments.

Pediatric Pointers

Cheyne-Stokes respirations rarely occur in children, except during late heart failure.

Geriatric Pointers

Cheyne-Stokes respirations can occur normally in elderly patients during sleep.

REFERENCES

D’Elia, E., Vanoli, E., La Rovere, M. T., Fanfulla, F., Maggioni, A., Casali, V., … Mortara, A. (2012). Adaptive servo ventilation reduces central sleep apnea in chronic heart failure patients: Beneficial effects on autonomic modulation of heart rate. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine, 14(4), 296–300.

Randerath, W. J., Nothofer, G., Priegnitz, C., Anduleit, N., Treml, M., Kehl, V., Galetke, W. (2012). Long-term auto servo-ventilation or constant positive pressure in heart failure and co-existing central with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest, 143(6), 1833.

Chills[Rigors]

Chills are extreme, involuntary muscle contractions with characteristic paroxysms of violent shivering and teeth chattering. Commonly accompanied by a fever, chills tend to arise suddenly, usually heralding the onset of infection. Certain diseases, such as pneumococcal pneumonia, produce only a single, shaking chill. Other diseases, such as malaria and Hodgkin’s disease (Pel-Ebstein fever), produce intermittent chills with recurring high fever. Still others produce continuous chills for up to 1 hour, precipitating a high fever. (See Why Chills Accompany Fever.)

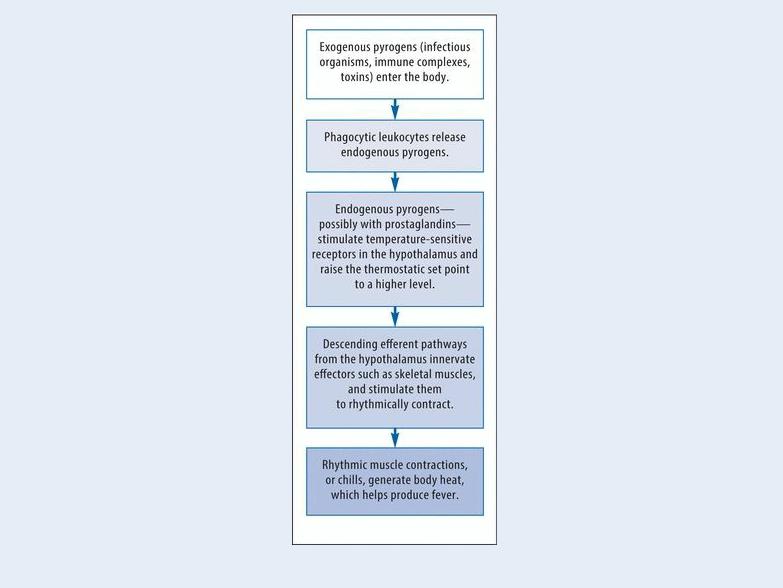

Why Chills Accompany Fever

Fever usually occurs when exogenous pyrogens activate endogenous pyrogens to reset the body’s thermostat to a higher level. At this higher set point, the body feels cold and responds through several compensatory mechanisms, including rhythmic muscle contractions or chills. These muscle contractions generate body heat and help produce fever. This flowchart outlines the events that link chills to fever.

Chills can also result from lymphomas, blood transfusion reactions, and certain drugs. Chills without fever occur as a normal response to exposure to cold. (See Rare Causes of Chills, page 166.)

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when the chills began and whether they’re continuous or intermittent. Because fever commonly accompanies or follows chills, take his rectal temperature to obtain a baseline reading. Then, check his temperature often to monitor fluctuations and to determine his temperature curve. Typically, a localized infection produces a sudden onset of shaking chills, sweats, and high fever. A systemic infection produces intermittent chills with recurring episodes of high fever or continuous chills that may last up to 1 hour and precipitate a high fever.

Ask about related signs and symptoms, such as headache, dysuria, diarrhea, confusion, abdominal pain, cough, sore throat, or nausea. Does the patient have any known allergies, an infection, or a recent history of an infectious disorder? Find out which medications he’s taking and whether a drug has improved or worsened his symptoms. Has he received treatment that may predispose him to an infection (such as chemotherapy)? Ask about recent exposure to farm and domestic animals such as guinea pigs, hamsters and dogs, and such birds as pigeons, parrots, and parakeets. Also, ask about recent insect or animal bites, travel to foreign countries, and contact with persons who have an active infection.

Medical Causes

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). AIDS is a commonly fatal disease that’s caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus transmitted by blood or semen. The patient usually develops lymphadenopathy and may also experience fatigue, anorexia and weight loss, diarrhea, diaphoresis, skin disorders, and signs of upper respiratory tract infection. Opportunistic infections can cause serious disease in the patient with AIDS.

Anthrax (inhalation). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease that’s caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Although the disease most commonly occurs in wild and domestic grazing animals, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, the spores can live in the soil for many years. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Most natural cases occur in agricultural regions worldwide. Anthrax may occur in a cutaneous, inhalation, or GI form.

Inhalation anthrax is caused by inhalation of aerosolized spores. Initial signs and symptoms are flulike and include a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain. The disease generally occurs in two stages with a period of recovery after the initial signs and symptoms. The second stage develops abruptly with rapid deterioration marked by a fever, dyspnea, stridor, and hypotension generally leading to death within 24 hours. Radiologic findings include mediastinitis and symmetric mediastinal widening.

Cholangitis. Charcot’s triad — chills with spiking fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and jaundice — characterizes a sudden obstruction of the common bile duct. The patient may have associated pruritus, weakness, and fatigue.

Gram-negative bacteremia. Gram-negative bacteremia causes sudden chills and a fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and prostration.

Hemolytic anemia. With acute hemolytic anemia, fulminating chills occur with a fever and abdominal pain. The patient rapidly develops jaundice and hepatomegaly; he may develop splenomegaly.

Hepatic abscess. Hepatic abscess usually arises abruptly, with chills, a fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and severe upper abdominal tenderness and pain that may radiate to the right shoulder.

Infective endocarditis. Infective endocarditis produces the abrupt onset of intermittent, shaking chills with a fever. Petechiae commonly develop. The patient may also have Janeway lesions on his hands and feet and Osler’s nodes on his palms and soles. Associated findings include a murmur, hematuria, eye hemorrhage, Roth’s spots, and signs of cardiac failure (dyspnea, peripheral edema).

Influenza. Initially, influenza causes an abrupt onset of chills, a high fever, malaise, a headache, myalgia, and a nonproductive cough. Some patients may also suddenly develop rhinitis, rhinorrhea, laryngitis, conjunctivitis, hoarseness, and a sore throat. Chills generally subside after the first few days, but an intermittent fever, weakness, and a cough may persist for up to 1 week. Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease, an acute febrile illness of unknown etiology, primarily affects children younger than 5 years of age, predominantly boys. Chills result from a high spiking fever that usually lasts 5 days or more. Accompanying symptoms include irritability, red eyes, bright red cracked lips, a strawberry tongue, swollen hands and feet, peeling skin on the fingertips and toes, and cervical lymphadenopathy. More severe complications include

inflammation in the walls of arteries throughout the body, including the coronary arteries. Standard treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin and aspirin substantially decreases the development of these coronary artery abnormalities, and most children recover without serious problems. Although Kawasaki disease occurs worldwide, with the highest incidence in Japan, it is a leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.

Legionnaires’ disease. Within 12 to 48 hours after the onset of Legionnaires’ disease, the patient suddenly develops chills and a high fever. Prodromal signs and symptoms characteristically include malaise, a headache, and possibly diarrhea, anorexia, diffuse myalgia, and general weakness. An initially nonproductive cough progresses to a productive cough with mucoid or mucopurulent sputum and possibly hemoptysis. The patient usually also develops nausea and vomiting, confusion, mild temporary amnesia, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, tachypnea, crackles, tachycardia, and flushed and mildly diaphoretic skin.

Rare Causes of Chills

Chills can result from disorders that rarely occur in the United States, but may be fairly common worldwide. Remember to ask about recent foreign travel when you obtain a patient’s history. Keep in mind this is only a partial list of rare disorders that produce chills.

Brucellosis (undulant fever)

Dengue fever (breakbone fever)

Epidemic typhus (louse-borne typhus)

Leptospirosis

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis

Monkey pox

Plague

Pulmonary tularemia

Rat bite fever

Relapsing fever

Malaria. The paroxysmal cycle of malaria begins with a period of chills lasting 1 to 2 hours. This is followed by a high fever lasting 3 to 4 hours and then 2 to 4 hours of profuse diaphoresis. Paroxysms occur every 48 to 72 hours when caused by Plasmodium malariae and every 40 to 42 hours when caused by P. vivax or P. ovale. With benign malaria, the paroxysms may be interspersed with periods of well-being. The patient also has a headache, muscle pain and, possibly, hepatosplenomegaly.

Monkey pox. Primarily a disease found in monkeys in central and western Africa, the monkey pox virus infrequently attacks humans. Several humans contracted the virus from infected prairie dogs in the United States in 2003. Initial symptoms of patients infected with monkey pox are chills resulting from a fever. Symptoms are similar to, but milder than, smallpox. Other common findings of this rare disease are sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, cough, shortness of breath, headache, muscle aches, backache, a general feeling of discomfort and exhaustion, and the development of a rash. There is no treatment for monkey pox infections. In certain cases, the

smallpox vaccine is used to protect individuals against monkey pox or to lessen the severity of the disease.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Pelvic inflammatory disease causes chills and fever with, typically, lower abdominal pain and tenderness; profuse, purulent vaginal discharge; or abnormal menstrual bleeding. The patient may also develop nausea and vomiting, an abdominal mass, and dysuria.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). Plague is one of the most virulent bacterial infections and, if untreated, one of the most potentially lethal diseases known. Most cases are sporadic, but the potential for epidemic spread still exists. Clinical forms include bubonic (the most common), septicemic, and pneumonic plagues. The bubonic form is transmitted to a human when bitten by an infected flea. Signs and symptoms include a fever, chills, and swollen, inflamed, and tender lymph nodes near the site of the flea bite. Septicemic plague develops as a fulminant illness generally with the bubonic form. The pneumonic form may be contracted from person to person through direct contact via the respiratory system or through biological warfare from aerosolization and inhalation of the organism. The onset is usually sudden with chills, a fever, headache, and myalgia. Pulmonary signs and symptoms include a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

Pneumonia. A single shaking chill usually heralds the sudden onset of pneumococcal pneumonia; other pneumonias characteristically cause intermittent chills. With any type of pneumonia, related findings may include a fever, a productive cough with bloody sputum, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia. The patient may be cyanotic and diaphoretic, with bronchial breath sounds and crackles, rhonchi, increased tactile fremitus, and grunting respirations. He may also experience achiness, anorexia, fatigue, and a headache.

Puerperal or postabortal sepsis. Chills and a high fever occur as early as 6 hours or as late as 10 days postpartum or postabortion. The patient may also have a purulent vaginal discharge, an enlarged and tender uterus, abdominal pain, backache and, possibly, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Pyelonephritis. With acute pyelonephritis, the patient develops chills, a high fever, and possibly nausea and vomiting over several hours to days. He generally also has anorexia, fatigue, myalgia, flank pain, costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, hematuria or cloudy urine, and urinary frequency, urgency, and burning.

Q fever. Q fever is a rickettsial disease caused by Coxiella burnetii. The primary source of human infection results from exposure to infected animals. Cattle, sheep, and goats are most likely to carry the organism. Human infection results from exposure to contaminated milk, urine, feces, or other fluids from infected animals. Infection may also result from inhalation of contaminated barnyard dust. C. burnetii is highly infectious and is considered a possible airborne agent for biological warfare. Signs and symptoms include a fever, chills, a severe headache, malaise, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The fever may last up to 2 weeks. In severe cases, the patient may develop hepatitis or pneumonia.

Renal abscess. Renal abscess initially produces sudden chills and a fever. Later effects include flank pain, CVA tenderness, abdominal muscle spasm, and transient hematuria.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Rocky Mountain spotted fever begins with a sudden onset of chills, a fever, malaise, an excruciating headache, and muscle, bone, and joint pain. Typically, the patient’s tongue is covered with a thick white coating that gradually turns brown. After 2 to 6

days of fever and occasional chills, a macular or maculopapular rash appears on the hands and feet and then becomes generalized; after a few days, the rash becomes petechial.

Septic arthritis. Chills and fever accompany the characteristic red, swollen, and painful joints caused by septic arthritis.

Septic shock. Initially, septic shock produces chills, a fever, and, possibly, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The patient’s skin is typically flushed, warm, and dry; his blood pressure is normal or slightly low; and he has tachycardia and tachypnea. As septic shock progresses, the patient’s arms and legs become cool and cyanotic, and he develops oliguria, thirst, anxiety, restlessness, confusion, and hypotension. Later, his skin becomes cold and clammy and his pulse, rapid and thready. He further develops severe hypotension, persistent oliguria or anuria, signs of respiratory failure, and coma.

Sinusitis. With acute sinusitis, chills occur along with a fever, a headache, and pain, tenderness, and swelling over the affected sinuses. Maxillary sinusitis produces pain over the cheeks and upper teeth; ethmoid sinusitis, pain over the eyes; frontal sinusitis, pain over the eyebrows; and sphenoid sinusitis, pain behind the eyes. The primary indicator of sinusitis is nasal discharge, which is commonly bloody for 24 to 48 hours before it gradually becomes purulent.

Snake bite. Most pit viper bites that result in envenomization cause chills, typically with a fever. Other systemic signs and symptoms include sweating, weakness, dizziness, fainting, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and thirst. The area around the snake bite may be marked by immediate swelling and tenderness, pain, ecchymoses, petechiae, blebs, bloody discharge, and local necrosis. The patient may have difficulty speaking, blurred vision, and paralysis. He may also show bleeding tendencies and signs of respiratory distress and shock.

Tularemia. Also known as rabbit fever, tularemia is an infectious disease that’s caused by the gram-negative, non–spore-forming bacterium Francisella tularensis. It’s typically a rural disease found in wild animals, water, and moist soil. It’s transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected insect or tick, handling infected animal carcasses, drinking contaminated water, or inhaling the bacteria. It’s considered a possible airborne agent for biological warfare. Signs and symptoms following inhalation of the organism include the abrupt onset of a fever, chills, a headache, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Typhus. Typhus is a rickettsial disease transmitted to humans by fleas, mites, or body lice. Initial signs and symptoms include a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise followed by an abrupt onset of chills, a fever, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

Violin spider bite. The violin spider bite produces chills, a fever, malaise, weakness, nausea, vomiting, and joint pain within 24 to 48 hours. The patient may also develop a rash and delirium.

Other Causes

Drugs. Amphotericin B is a drug associated with chills. Phenytoin is also a common cause of drug-induced fever that can produce chills. I.V. bleomycin and intermittent administration of an oral antipyretic can also cause chills.

I.V. therapy. Infection at the I.V. insertion site (superficial phlebitis) can cause chills, high