Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfPatient Counseling

Instruct the patient to perform regular mouth care, particularly before meals, because reducing foul mouth taste and odor may stimulate his appetite. Tell him to use a half-strength hydrogen peroxide mixture of lemon juice gargle to help neutralize the ammonia. Recommend the use of commercial lozenges or breath sprays or to suck on hard candy to freshen his breath. Advise him to use a soft toothbrush or sponge to prevent trauma. Teach the patient about the cause of the ammonia breath odor after a diagnosis is established.

Pediatric Pointers

Ammonia breath odor also occurs in children with end-stage chronic renal failure. Provide hard candies to relieve bad mouth taste and odor. If the child is able to gargle, try mixing hydrogen peroxide with flavored mouthwashes.

REFERENCES

Kreuzer, P ., Langguth, B., Popp, R., Raster, R., Busch, V,, Frank, E., … Landgrebe, M. (2011). Reduced intra-cortical inhibition after sleep deprivation: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neuroscience Letter, 493(3), 63–66.

Lo, J. C., Groeger, J. A. , Santhi, N. , Arbon, E. L., Lazar, A. S. , Hasan, S., … Dijk, D. J. Effects of partial and acute total sleep deprivation on performance across cognitive domains, individuals and circadian phase. PLoS One, 7(9), e45987.

Breath with Fecal Odor

Fecal breath odor typically accompanies fecal vomiting associated with a long-standing intestinal obstruction or gastrojejunocolic fistula. It represents an important late diagnostic clue to a potentially life-threatening GI disorder because complete obstruction of any part of the bowel, if untreated, can cause death within hours from vascular collapse and shock.

When the obstructed or adynamic intestine attempts self-decompression by regurgitating its contents, vigorous peristaltic waves propel bowel contents backward into the stomach. When the stomach fills with intestinal fluid, further reverse peristalsis results in vomiting. The odor of feculent vomitus lingers in the mouth.

Fecal breath odor may also occur in patients with a nasogastric (NG) or intestinal tube. The odor is detected only while the underlying disorder persists and abates soon after its resolution.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Because fecal breath odor signals a potentially life-threatening intestinal obstruction, you’ll need to quickly evaluate the patient’s condition. Monitor his vital signs, and be alert for signs of shock, such as hypotension, tachycardia, narrowed pulse pressure, and cool, clammy skin. Ask the patient if he’s experiencing nausea or has vomited. Find out the frequency of vomiting as well as the color, odor, amount, and consistency of the vomitus. Have an emesis basin nearby to collect and accurately measure the vomitus.

Anticipate possible surgery to relieve an obstruction or repair a fistula, and withhold all food and fluids. Be prepared to insert an NG or intestinal tube for GI tract decompression. Insert a peripheral I.V. line for vascular access, or assist with central line insertion for

large-bore access and central venous pressure monitoring. Obtain a blood sample and send it to the laboratory for complete blood count and electrolyte analysis because large fluid losses and shifts can produce electrolyte imbalances. Maintain adequate hydration, and support circulatory status with additional fluids. Give a physiologic solution — such as lactated Ringer’s solution or normal saline or Plasmanate — to prevent metabolic acidosis from gastric losses and metabolic alkalosis from intestinal fluid losses.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask about previous abdominal surgery because adhesions can cause an obstruction. Also, ask about loss of appetite. Is the patient experiencing abdominal pain? If so, have him describe its onset, duration, and location. Ask if the pain is intense, persistent, or spasmodic. Have the patient describe his normal bowel habits, especially noting constipation, diarrhea, or leakage of stool. Ask when the patient’s last bowel movement occurred, and have him describe the stool’s color and consistency.

Auscultate for bowel sounds — hyperactive, high-pitched sounds may indicate impending bowel obstruction, whereas hypoactive or absent sounds occur late in obstruction and paralytic ileus. Inspect the abdomen, noting its contour and any surgical scars. Measure abdominal girth to provide baseline data for subsequent assessment of distention. Palpate for tenderness, distention, and rigidity. Percuss for tympany, indicating a gas-filled bowel, and dullness, indicating fluid.

Rectal and pelvic examinations should be performed. All patients with a suspected bowel obstruction should have a flat and upright abdominal X-ray; some will also need a chest X-ray, sigmoidoscopy, and barium enema.

Medical Causes

Distal small-bowel obstruction. With late obstruction, nausea is present although vomiting may be delayed. Vomitus initially consists of gastric contents, then changes to bilious contents, followed by fecal contents with resultant fecal breath odor. Accompanying symptoms include achiness, malaise, drowsiness, and polydipsia. Bowel changes (ranging from diarrhea to constipation) are accompanied by abdominal distention, persistent epigastric or periumbilical colicky pain, and hyperactive bowel sounds and borborygmi. As the obstruction becomes complete, bowel sounds become hypoactive or absent. Fever, hypotension, tachycardia, and rebound tenderness may indicate strangulation or perforation.

Gastrojejunocolic fistula. With gastrojejunocolic fistula, symptoms may be variable and intermittent because of temporary plugging of the fistula. Fecal vomiting with resulting fecal breath odor may occur, but the most common chief complaint is diarrhea, accompanied by abdominal pain. Related GI findings include anorexia, weight loss, abdominal distention, and, possibly, marked malabsorption.

Large-bowel obstruction. Vomiting is usually absent initially, but fecal vomiting with resultant fecal breath odor occurs as a late sign. Typically, symptoms develop more slowly than in smallbowel obstruction. Colicky abdominal pain appears suddenly, followed by continuous hypogastric pain. Marked abdominal distention and tenderness occur, and loops of large bowel may be visible through the abdominal wall. Although constipation develops, defecation may continue for up to 3 days after complete obstruction because of stool remaining in the bowel

below the obstruction. Leakage of stool is common with partial obstruction.

Special Considerations

After an NG or intestinal tube has been inserted, keep the head of the bed elevated at least 30 degrees and turn the patient to facilitate passage of the intestinal tube through the GI tract. Don’t tape the intestinal tube to the patient’s face. Ensure tube patency by monitoring drainage and watching that suction devices function properly. Irrigate as required. Monitor GI drainage, and send serum specimens to the laboratory for electrolyte analysis at least once per day. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as abdominal X-rays, barium enema, and proctoscopy.

Patient Counseling

Explain to the patient the procedures and treatments he needs. Teach the patient the techniques of good oral hygiene, and explain food and fluid restrictions that are needed.

Pediatric Pointers

Carefully monitor the child’s fluid and electrolyte status because dehydration can occur rapidly from persistent vomiting. The absence of tears and dry or parched mucous membranes are important clinical signs of dehydration.

Geriatric Pointers

In older patients, early surgical intervention may be necessary for a bowel obstruction that doesn’t respond to decompression because of the high risk of bowel infarct.

REFERENCES

Packey, C. D., & Sartor, R. B. (2009) . Commensal bacteria, traditional and opportunistic pathogens, dysbiosis and bacterial killing in inflammatory bowel diseases. Current Opinion in Infectious Disease, 22, 292–301.

Reiff, C., & Kelly, D. (2010) . Inflammatory bowel disease, gut bacteria and probiotic therapy. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 300, 25–33.

Breath with Fruity Odor

Fruity breath odor results from respiratory elimination of excess acetone. This sign characteristically occurs with ketoacidosis — a potentially life-threatening condition that requires immediate treatment to prevent severe dehydration, irreversible coma, and death.

Ketoacidosis results from the excessive catabolism of fats for cellular energy in the absence of usable carbohydrates. This process begins when insulin levels are insufficient to transport glucose into the cells, as in diabetes mellitus, or when glucose is unavailable and hepatic glycogen stores are depleted, as in low-carbohydrate diets and malnutrition. Lacking glucose, the cells burn fat faster than enzymes can handle the ketones, the acidic end products. As a result, the ketones (acetone, betahydroxybutyric acid, and acetoacetic acid) accumulate in the blood and urine. To compensate for increased acidity, Kussmaul’s respirations expel carbon dioxide with enough acetone to flavor the breath. Eventually, this compensatory mechanism fails, producing ketoacidosis.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

When you detect fruity breath odor, check for Kussmaul’s respirations and examine the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Take his vital signs, and check skin turgor. Be alert for fruity breath odor that accompanies rapid, deep respirations, stupor, and poor skin turgor. Try to obtain a brief history, noting especially diabetes mellitus, nutritional problems such as anorexia nervosa, and fad diets with little or no carbohydrates. Obtain venous and arterial blood samples for glucose, complete blood count, and electrolyte, acetone, and arterial blood gas (ABG) levels. Also, obtain a urine specimen to test for glucose and acetone. Administer I.V. fluids and electrolytes to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance and, in the patient with diabetic ketoacidosis, give regular insulin to reduce blood glucose levels.

If the patient is obtunded, you’ll need to insert endotracheal and nasogastric (NG) tubes. Suction as needed. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter, and monitor intake and output. Insert central venous pressure and arterial lines to monitor the patient’s fluid status and blood pressure. Place the patient on a cardiac monitor, monitor his vital signs and neurologic status, and draw blood hourly to check glucose, electrolyte, acetone, and ABG levels.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, obtain a thorough history. Ask about the onset and duration of fruity breath odor. Find out about changes in breathing pattern. Ask about increased thirst, frequent urination, weight loss, fatigue, and abdominal pain. Ask the female patient if she has had candidal vaginitis or vaginal secretions with itching. If the patient has a history of diabetes mellitus, ask about stress, infections, and noncompliance with therapy — the most common causes of ketoacidosis in known diabetics. If the patient is suspected of having anorexia nervosa, obtain a dietary and weight history.

Medical Causes

Anorexia nervosa. Severe weight loss associated with anorexia nervosa may produce fruity breath, usually with nausea, constipation, and cold intolerance, as well as dental enamel erosion and scars or calluses in the dorsum of the hand, both related to induced vomiting.

Ketoacidosis. Fruity breath odor accompanies alcoholic ketoacidosis, which is usually seen in poorly nourished alcoholics with vomiting, abdominal pain, and only minimal food intake over several days. Kussmaul’s respirations begin abruptly and accompany dehydration, abdominal pain and distention, and absent bowel sounds. Blood glucose levels are normal or slightly decreased.

With diabetic ketoacidosis, fruity breath odor commonly occurs as ketoacidosis develops over 1 to 2 days. Other findings include polydipsia, polyuria, nocturia, a weak and rapid pulse, hunger, weight loss, weakness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Eventually, Kussmaul’s respirations, orthostatic hypotension, dehydration, tachycardia, confusion, and stupor occur. Signs and symptoms may lead to coma.

Starvation ketoacidosis is a potentially life-threatening disorder that has a gradual onset. Besides fruity breath odor, typical findings include signs of cachexia and dehydration, a

decreased LOC, bradycardia, and a history of severely limited food intake (anorexia nervosa).

Other Causes

Drugs. Any drug known to cause metabolic acidosis, such as nitroprusside and salicylates, can result in fruity breath odor.

Low-carbohydrate diets. These diets, which encourage little or no carbohydrate intake, may cause ketoacidosis and the resulting fruity breath odor.

Special Considerations

Provide emotional support for the patient and his family. Explain tests and treatments clearly. When the patient is more alert and his condition stabilizes, remove the NG tube and start him on an appropriate diet. Switch his insulin from the I.V. to the subcutaneous route.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms of hyperglycemia. Emphasize the importance of wearing medical identification. Refer the patient to a psychological or support group, as needed.

Pediatric Pointers

Fruity breath odor in an infant or child usually stems from uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Ketoacidosis develops rapidly in this age group because of low glycogen reserves. As a result, prompt administration of insulin and correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance are necessary to prevent shock and death.

Geriatric Pointers

The elderly patient may have poor oral hygiene, increased dental caries, decreased salivary function with dryness, and poor dietary intake. In addition, he may take multiple drugs. Consider all of these factors when evaluating an elderly patient with mouth odor.

REFERENCES

Kitabchi, A. E., Umpierrez, G. E., Miles, J. M., & Fisher, J. N. (2009). Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 32, 1335–1343.

Wolfsdorf, J., Craig, M. E., Daneman, D., Dunger, D., Edge, J., Lee, W., … Hanas, R. (2009) . Diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 10, 118–133.

Brudzinski’s Sign

A positive Brudzinski’s sign (flexion of the hips and knees in response to passive flexion of the neck) signals meningeal irritation. Passive flexion of the neck stretches the nerve roots, causing pain and involuntary flexion of the knees and hips.

Brudzinski’s sign is a common and important early indicator of life-threatening meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. It can be elicited in children as well as adults, although more reliable indicators of meningeal irritation exist for infants.

Testing for Brudzinski’s sign isn’t part of the routine examination, unless meningeal irritation is suspected. (See Testing for Brudzinski’s Sign.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient is alert, ask him about headache, neck pain, nausea, and vision disturbances (blurred or double vision and photophobia) — all indications of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Next, observe the patient for signs and symptoms of increased ICP, such as an altered level of consciousness (LOC) (restlessness, irritability, confusion, lethargy, personality changes, and coma), pupillary changes, bradycardia, widened pulse pressure, irregular respiratory patterns (Cheyne-Stokes or Kussmaul’s respirations), vomiting, and moderate fever.

Keep artificial airways, intubation equipment, a handheld resuscitation bag, and suction equipment on hand because the patient’s condition may suddenly deteriorate. Elevate the head of his bed 30 to 60 degrees to promote venous drainage. Administer an osmotic diuretic, such as mannitol, to reduce cerebral edema.

Monitor ICP and be alert for ICP that continues to rise. You may have to provide mechanical ventilation and administer a barbiturate and additional doses of a diuretic. Also, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may have to be drained.

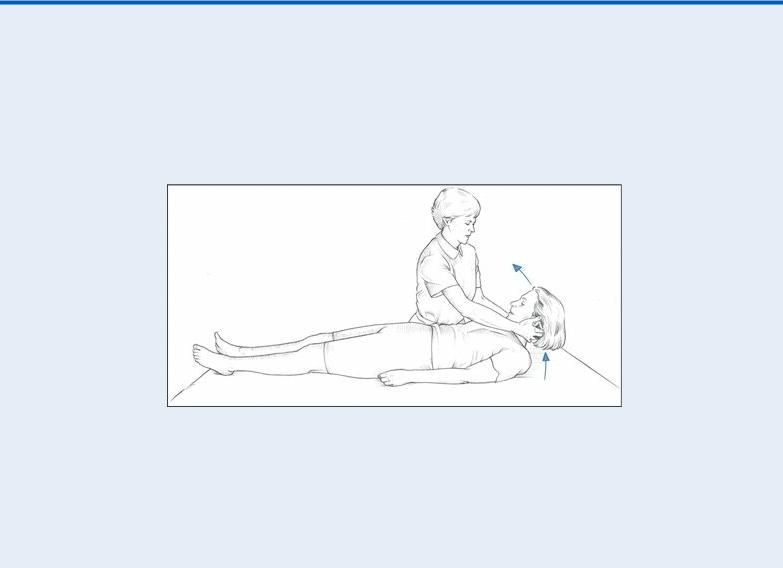

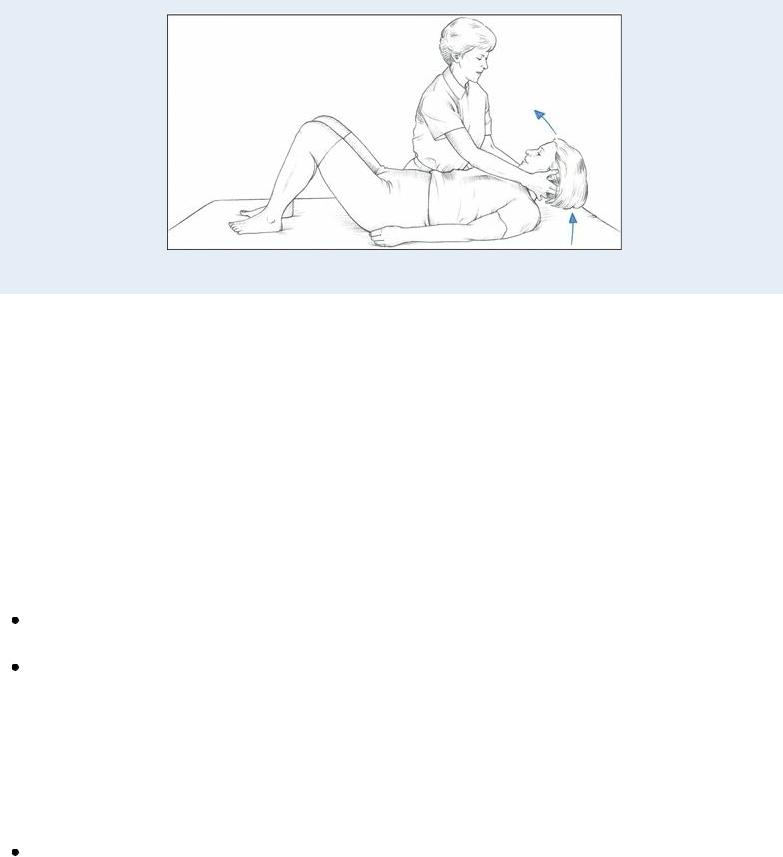

EXAMINATION TIP Testing for Brudzinski’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Testing for Brudzinski’s Sign

Here’s how to test for Brudzinski’s sign when you suspect meningeal irritation:

With the patient in a supine position, place your hands behind her neck and lift her head toward her chest.

If your patient has meningeal irritation, she’ll flex her hips and knees in response to the passive neck flexion.

History and Physical Examination

Continue your neurologic examination by evaluating the patient’s cranial nerve function, noting motor or sensory deficits. Be sure to look for Kernig’s sign (resistance to knee extension after flexion of the hip), which is a further indication of meningeal irritation. Also, look for signs of central nervous system infection, such as fever and nuchal rigidity.

Ask the patient or his family, if necessary, about a history of hypertension, spinal arthritis, or recent head trauma. Also, ask about dental work and abscessed teeth (a possible cause of meningitis), open head injury, endocarditis, and I.V. drug abuse. Ask about sudden onset of headaches, which may be associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Medical Causes

Arthritis. With severe spinal arthritis, a positive Brudzinski’s sign can occasionally be elicited. The patient may also report back pain (especially after weight bearing) and limited mobility. Meningitis. A positive Brudzinski’s sign can usually be elicited 24 hours after the onset of meningitis, a life-threatening disorder. Accompanying findings may include headache, a positive Kernig’s sign, nuchal rigidity, irritability or restlessness, deep stupor or coma, vertigo, fever (high or low, depending on the severity of the infection), chills, malaise, hyperalgesia, muscular hypotonia, opisthotonos, symmetrical deep tendon reflexes, papilledema, ocular and facial palsies, nausea and vomiting, photophobia, diplopia, and unequal sluggish pupils. As ICP rises, arterial hypertension, bradycardia, widened pulse pressure, Cheyne-Stokes or Kussmaul’s respirations, and coma may develop.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brudzinski’s sign may be elicited within minutes after initial bleeding in subarachnoid hemorrhage, a life-threatening disorder. Accompanying signs and symptoms include the sudden onset of severe headache, nuchal rigidity, altered LOC, dizziness, photophobia, cranial nerve palsies (as evidenced by ptosis, pupil dilation, and limited extraocular muscle movement), nausea and vomiting, fever, and a positive Kernig’s sign. Focal signs — such as hemiparesis, vision disturbances, or aphasia — may also occur. As ICP rises, arterial hypertension, bradycardia, widened pulse pressure, Cheyne-Stokes or Kussmaul’s respirations, and coma may develop.

Special Considerations

Many patients with a positive Brudzinski’s sign are critically ill. They need constant ICP monitoring and frequent neurologic checks in addition to intensive assessment and monitoring of vital signs, intake and output, and cardiorespiratory status. To promote patient comfort, maintain low lights and minimal noise and elevate the head of the bed. The patient usually won’t receive an opioid analgesic because it may mask signs of increased ICP.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests. These may include blood, urine, and sputum cultures to identify bacteria, lumbar puncture to assess CSF and relieve pressure, and computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, cerebral angiography, and spinal X-rays to locate a hemorrhage.

Patient Counseling

Discuss the signs and symptoms of meningitis and subdural hematoma. Tell the patient when to seek immediate medical attention.

Pediatric Pointers

Brudzinski’s sign may not be useful as an indicator of meningeal irritation in infants because more reliable signs (such as bulging fontanels, a weak cry, fretfulness, vomiting, and poor feeding) appear early.

REFERENCES

CDC. (2011). Multistate outbreak of listeriosis associated with Jensen Farms cantaloupe—United States, August–September. MMWR Morbidity and Mortal Weekly Report, 60, 1357–1358.

Todd, E. C., & Notermans, S. (2011). Surveillance of listeriosis and its causative pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control, 22, 1484–1490.

Bruits

Commonly an indicator of lifeor limb-threatening vascular disease, bruits are swishing sounds caused by turbulent blood flow. They’re characterized by location, duration, intensity, pitch, and the time of onset in the cardiac cycle. Loud bruits produce intense vibration and a palpable thrill. A thrill, however, doesn’t provide a further clue to the causative disorder or to its severity.

Bruits are most significant when heard over the abdominal aorta; the renal, carotid, femoral, popliteal, or subclavian artery; or the thyroid gland. (See Preventing False Bruits, page 138.) They’re also significant when heard consistently despite changes in patient position and when heard during diastole.

History and Physical Examination

If you detect bruits over the abdominal aorta, check for a pulsating mass or a bluish discoloration around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign). Either of these signs — or severe, tearing pain in the abdomen, flank, or lower back — may signal life-threatening dissection of an aortic aneurysm. Also, check peripheral pulses, comparing intensity in the upper versus lower extremities.

If you suspect dissection, monitor the patient’s vital signs constantly, and withhold food and fluids until a definitive diagnosis is made. Watch for signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock, such as

thirst; hypotension; tachycardia; a weak, thready pulse; tachypnea; an altered level of consciousness (LOC); mottled knees and elbows; and cool, clammy skin.

If you detect bruits over the thyroid gland, ask the patient if he has a history of hyperthyroidism or signs and symptoms of it, such as nervousness, tremors, weight loss, palpitations, heat intolerance, and (in females) amenorrhea. Watch for signs and symptoms of life-threatening thyroid storm, such as tremor, restlessness, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatomegaly.

If you detect carotid artery bruits, be alert for signs and symptoms of a transient ischemic attack (TIA), including dizziness, diplopia, slurred speech, flashing lights, and syncope. These findings may indicate an impending stroke. Be sure to evaluate the patient frequently for changes in LOC and muscle function.

If you detect bruits over the femoral, popliteal, or subclavian artery, watch for signs and symptoms of decreased or absent peripheral circulation — edema, weakness, and paresthesia. Ask the patient if he has a history of intermittent claudication. Frequently check distal pulses, skin color, and temperature. Also, watch for the sudden absence of pulse, pallor, or coolness, which may indicate a threat to the affected limb.

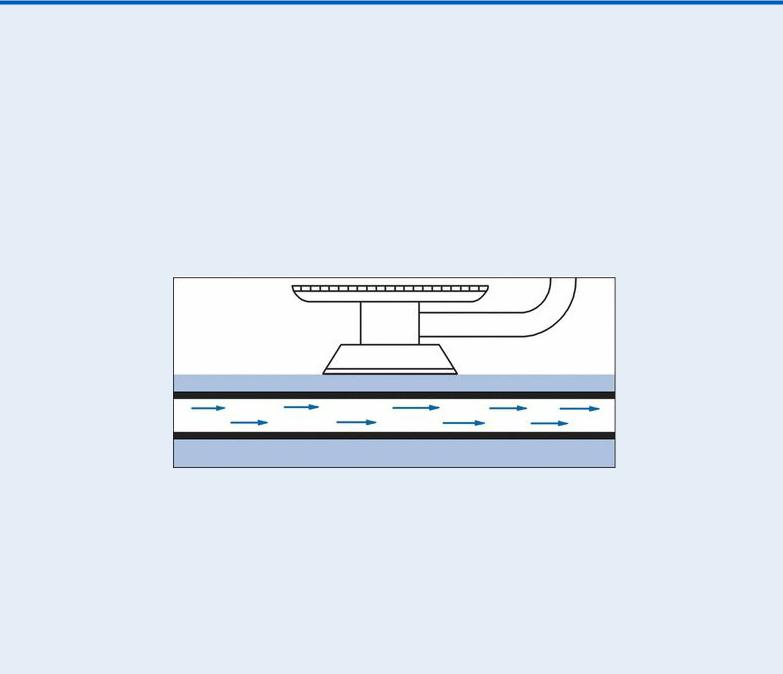

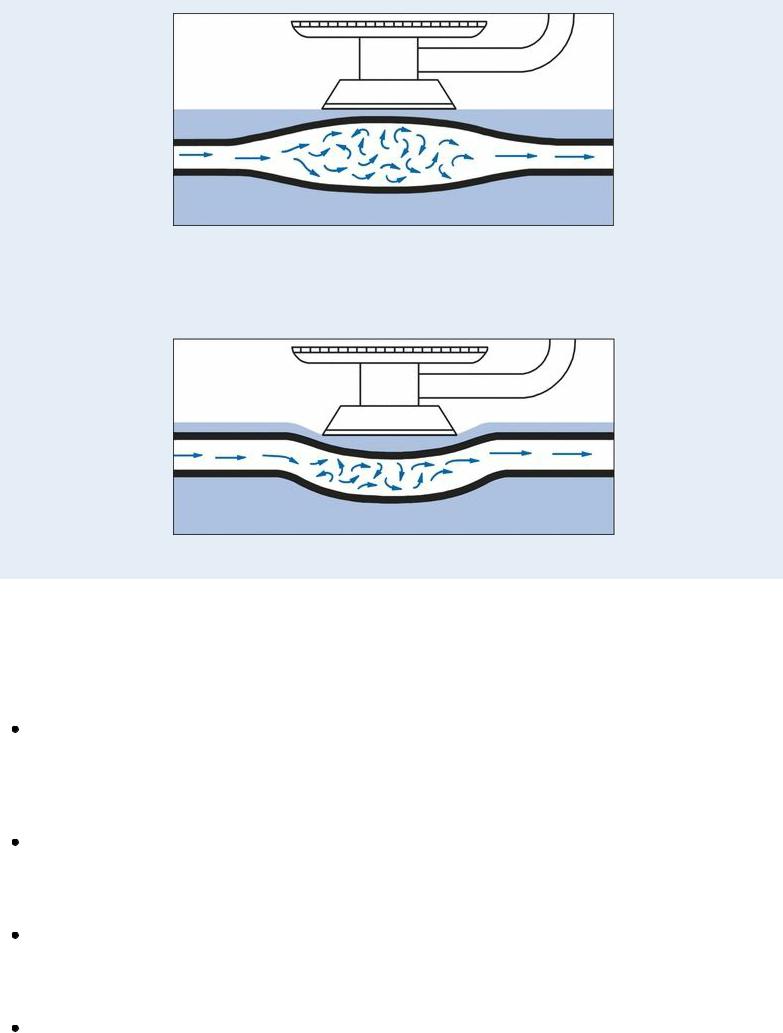

EXAMINATION TIP Preventing False Bruits

EXAMINATION TIP Preventing False Bruits

Auscultating bruits accurately requires practice and skill. These sounds typically stem from arterial luminal narrowing or arterial dilation, but they can also result from excessive pressure applied to the stethoscope’s bell during auscultation. This pressure compresses the artery, creating turbulent blood flow and a false bruit.

To prevent false bruits, place the bell lightly on the patient’s skin. Also, if you’re auscultating for a popliteal bruit, help the patient to a supine position, place your hand behind his ankle, and lift his leg slightly before placing the bell behind the knee.

Normal Blood Flow, No Bruit

Turbulent Blood Flow and Resultant Bruit Caused by Aneurysm

Turbulent Blood Flow and False Bruit Caused by Compression of Artery

If you detect a bruit, make sure to check for further vascular damage and perform a thorough cardiac assessment.

Medical Causes

Abdominal aortic aneurysm. A pulsating periumbilical mass accompanied by a systolic bruit over the aorta characterizes abdominal aortic aneurysm. Associated signs and symptoms include a rigid, tender abdomen, mottled skin, diminished peripheral pulses, and claudication. Sharp, tearing pain in the abdomen, flank, or lower back signals imminent dissection.

Abdominal aortic atherosclerosis. Loud systolic bruits in the epigastric and midabdominal areas are common. They may be accompanied by leg weakness, numbness, paresthesia, or paralysis; leg pain; or decreased or absent femoral, popliteal, or pedal pulses. Abdominal pain is rarely present.

Anemia. Increased cardiac output causes increased blood flow. In patients with severe anemia, short systolic bruits may be heard over both carotid arteries and may be accompanied by headache, fatigue, dizziness, pallor, jaundice, palpitations, mild tachycardia, dyspnea, nausea, anorexia, and glossitis.

Carotid artery stenosis. Systolic bruits can be heard over one or both carotid arteries. Other