Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Chest Expansion, Asymmetrical

Asymmetrical chest expansion is the uneven extension of portions of the chest wall during inspiration. During normal respiration, the thorax uniformly expands upward and outward and then contracts downward and inward. When this process is disrupted, breathing becomes uncoordinated, resulting in asymmetrical chest expansion.

Asymmetrical chest expansion may develop suddenly or gradually and may affect one or both sides of the chest wall. It may occur as delayed expiration (chest lag), as abnormal movement during inspiration (for example, intercostal retractions, paradoxical movement, or chest-abdomen asynchrony), or as a unilateral absence of movement. This sign usually results from pleural disorders, such as life-threatening hemothorax or tension pneumothorax. (See Recognizing Life-threatening Causes of Asymmetrical Chest Expansion.) However, it can also result from a musculoskeletal or urologic disorder, airway obstruction, or trauma. Regardless of its underlying cause, asymmetrical chest expansion produces rapid and shallow or deep respirations that increase the work of breathing.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect asymmetrical chest expansion, first consider traumatic injury to the patient’s ribs or sternum, which can cause flail chest, a life-threatening emergency characterized by paradoxical chest movement. Quickly take the patient’s vital signs, and look for signs of acute respiratory distress — rapid and shallow respirations, tachycardia, and cyanosis. Use tape or sandbags to temporarily splint the unstable flail segment.

Depending on the severity of respiratory distress, administer oxygen by nasal cannula, mask, or mechanical ventilator. Insert an I.V. line to allow fluid replacement and administration of pain medication. Draw a blood sample from the patient for arterial blood gas analysis, and connect the patient to a cardiac monitor.

Although asymmetrical chest expansion may result from hemothorax, tension pneumothorax, bronchial obstruction, and other life-threatening causes, it isn’t a cardinal sign of these disorders. Because any form of asymmetrical chest expansion can compromise the patient’s respiratory status, don’t leave the patient unattended, and be alert for signs of respiratory distress.

Recognizing Life-Threatening Causes of Asymmetrical Chest

Expansion

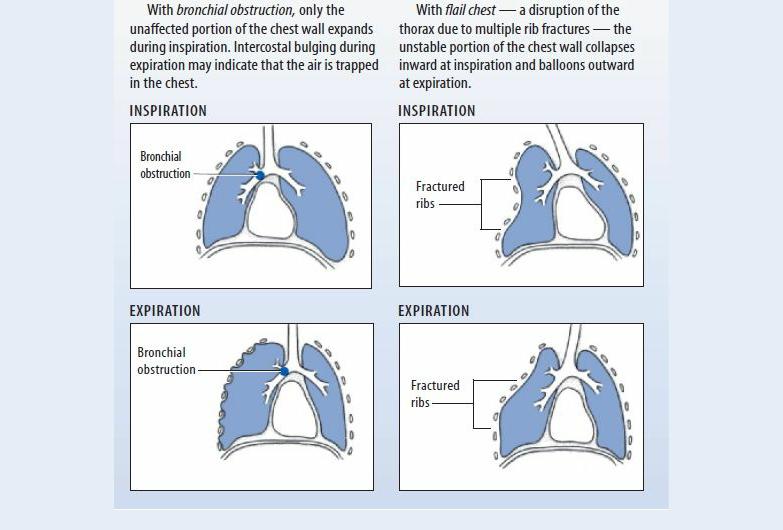

Asymmetrical chest expansion can result from several life-threatening disorders. Two common causes — bronchial obstruction and flail chest — produce distinctive chest wall movements that provide important clues about the underlying disorder.

History and Physical Examination

If you don’t suspect flail chest and if the patient isn’t experiencing acute respiratory distress, obtain a brief history. Asymmetrical chest expansion commonly results from mechanical airflow obstruction, so find out if the patient is experiencing dyspnea or pain during breathing. If so, does he feel short of breath constantly or intermittently? Does the pain worsen his feeling of breathlessness? Does repositioning, coughing, or other activity relieve or worsen the patient’s dyspnea or pain? Is the pain more noticeable during inspiration or expiration? Can he inhale deeply?

Ask if the patient has a history of pulmonary or systemic illness, such as frequent upper respiratory tract infections, asthma, tuberculosis, pneumonia, or cancer. Has he had thoracic surgery? (This typically produces asymmetrical chest expansion on the affected side.) Also, ask about blunt or penetrating chest trauma, which may have caused pulmonary injury. Obtain an occupational history to find out if the patient may have inhaled toxic fumes or aspirated a toxic substance.

Next, perform a physical examination. Begin by gently palpating the trachea for midline positioning. (Deviation of the trachea usually indicates an acute problem requiring immediate intervention.) Then, examine the posterior chest wall for areas of tenderness or deformity. To evaluate the extent of asymmetrical chest expansion, place your hands — fingers together and thumbs abducted toward the spine — flat on both sections of the lower posterior chest wall. Position your thumbs at the 10th rib, and grasp the lateral rib cage with your hands. As the patient inhales, note the uneven separation of your thumbs, and gauge the distance between them. Then, repeat this technique on the upper posterior chest wall. Next, use the ulnar surface of your hand to palpate for vocal or

tactile fremitus on both sides of the chest. To check for vocal fremitus, ask the patient to repeat “99” as you proceed. Note asymmetrical vibrations and areas of enhanced, diminished, or absent fremitus. Then, percuss and auscultate to detect air and fluid in the lungs and pleural spaces. Finally, auscultate all lung fields for normal and adventitious breath sounds. Examine the patient’s anterior chest wall, using the same assessment techniques.

Medical Causes

Bronchial obstruction. Life-threatening loss of airway patency may occur gradually or suddenly. Typically, a lack of chest movement indicates complete obstruction; chest lag signals partial obstruction. If air is trapped in the chest, you may detect intercostal bulging during expiration and hyperresonance on percussion. You may also note dyspnea; accessory muscle use; decreased or absent breath sounds; and suprasternal, substernal, or intercostal retractions.

Flail chest. With flail chest, a life-threatening injury to the ribs or sternum, the unstable portion of the chest wall collapses inward during inspiration and balloons outward during expiration (paradoxical movement). The patient may have ecchymoses, severe localized pain, or other signs of traumatic injury to the chest wall. He may also exhibit rapid, shallow respirations, tachycardia, and cyanosis.

Hemothorax. Hemothorax is life-threatening bleeding into the pleural space that causes chest lag during inspiration. Other findings include signs of traumatic chest injury, stabbing pain at the injury site, anxiety, dullness on percussion, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia. If hypovolemia occurs, you’ll note signs of shock, such as hypotension and a rapid, weak pulse.

Kyphoscoliosis. Abnormal curvature of the thoracic spine in the anteroposterior direction (kyphosis) and the lateral direction (scoliosis) gradually compresses one lung and distends the other. This produces decreased chest wall movement on the compressed lung side and expands the intercostal muscles during inspiration on the opposite side. It can also produce ineffective coughing, dyspnea, back pain, and fatigue.

Myasthenia gravis. Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular disease distinguished by varying degrees of weakness of voluntary muscles. The muscles that control breathing can be affected. Progressive loss of ventilatory muscle function produces asynchrony of the chest and abdomen during inspiration (“abdominal paradox”), which can lead to the onset of acute respiratory distress. Typically, the patient’s shallow respirations and increased muscle weakness cause severe dyspnea, tachypnea, and possible apnea.

Pleural effusion. Chest lag at end-inspiration occurs gradually in this life-threatening accumulation of fluid, blood, or pus in the pleural space. Usually, some combination of dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia precedes chest lag; the patient may also have pleuritic pain that worsens with coughing or deep breathing. The area of the effusion is delineated by dullness on percussion and by egophony, bronchophony, whispered pectoriloquy, decreased or absent breath sounds, and decreased tactile fremitus. A fever appears if infection causes the effusion.

Pneumonia. Depending on whether fluid consolidation in the lungs develops unilaterally or bilaterally, asymmetrical chest expansion occurs as inspiratory chest lag or as chest-abdomen asynchrony. The patient typically has a fever, chills, tachycardia, tachypnea, and dyspnea along with crackles, rhonchi, and chest pain that worsens during deep breathing. He may also be fatigued and anorexic and have a productive cough with rust-colored sputum.

Pneumothorax. Entrapment of air in the pleural space can cause chest lag at end-inspiration.

Pneumothorax, a life-threatening condition, also causes sudden, stabbing chest pain that may radiate to the arms, face, back, or abdomen and dyspnea unrelated to the chest pain’s severity. Other findings include tachypnea, decreased tactile fremitus, tympany on percussion, decreased or absent breath sounds over the trapped air, tachycardia, restlessness, and anxiety.

With tension pneumothorax, the same signs and symptoms occur as in pneumothorax, but they’re much more severe. Tension pneumothorax rapidly compresses the heart and great vessels, causing cyanosis, hypotension, tachycardia, restlessness, and anxiety. The patient may also develop subcutaneous crepitation of the upper trunk, neck, and face, and mediastinal and tracheal deviation away from the affected side. You may auscultate a crunching sound over the precordium with each heartbeat; this indicates pneumomediastinum.

Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism is an acute, life-threatening disorder that causes chest lag; sudden, stabbing chest pain; and tachycardia. The patient usually has severe dyspnea, blood-tinged sputum, a pleural friction rub, and acute anxiety.

Other Causes

Treatments. Asymmetrical chest expansion can result from pneumonectomy and the surgical removal of several ribs. Chest lag or the absence of chest movement may also result from intubation of a mainstem bronchus, a serious complication typically due to the incorrect insertion of an endotracheal tube or movement of the tube while it’s in the trachea.

Special Considerations

If you’re caring for an intubated patient, regularly auscultate breath sounds in the lung peripheries to help detect a misplaced tube. If this occurs, prepare the patient for a chest X-ray to allow rapid repositioning of the tube. Because asymmetrical chest expansion increases the work of breathing, supplemental oxygen is usually given during acute events.

Patient Counseling

Explain to the patient or caregiver how to recognize early signs and symptoms of respiratory distress and what to do if they occur. Teach the patient coughing and deep breathing exercises and techniques that can help reduce anxiety.

Pediatric Pointers

Children have a greater risk than adults of mainstem bronchi (especially left bronchus) intubation. However, because children’s breath sounds are usually referred from one lung to the other because of the small size of the thoracic cage, use chest wall expansion as an indicator of correct tube position. Children also develop asymmetrical chest expansion, paradoxical breathing, and retractions with acute respiratory illnesses, such as bronchiolitis, asthma, and croup.

Congenital abnormalities, such as cerebral palsy and diaphragmatic hernia, can also cause asymmetrical chest expansion. With cerebral palsy, asymmetrical facial muscles usually accompany chest-abdomen asynchrony. With a life-threatening diaphragmatic hernia, asymmetrical expansion usually occurs on the left side of the chest.

Geriatric Pointers

Asymmetrical chest expansion may be more difficult to determine in this population because of the structural deformities associated with aging.

REFERENCES

Mohammad, A. , Branicki, F., & Abu-Zidan, F. M. (2013) . Educational and clinical impact of advanced trauma life support (ATLS) courses: A systematic review. World Journal of Surgery 38(2): 322–329.

Shere-Wolfe, R. F. , Galvagno, S. M., & Grissom, T. E. (2012). Critical care considerations in the management of the trauma patient following initial resuscitation. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma and Resuscitative Emergency Medicine, 20, 68.

Chest Pain

Chest pain usually results from disorders that affect thoracic or abdominal organs — the heart, pleurae, lungs, esophagus, rib cage, gallbladder, pancreas, or stomach. An important indicator of several acute and life-threatening cardiopulmonary and GI disorders, chest pain can also result from a musculoskeletal or hematologic disorder, anxiety, and drug therapy.

Chest pain can arise suddenly or gradually, and its cause may be difficult to ascertain initially. The pain can radiate to the arms, neck, jaw, or back. It can be steady or intermittent, mild or acute. It can range in character from a sharp shooting sensation to a feeling of heaviness, fullness, or even indigestion. It can be provoked or aggravated by stress, anxiety, exertion, deep breathing, or eating certain foods.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Ask the patient when his chest pain began. Did it develop suddenly or gradually? Is it more severe or frequent now than when it first started? Does anything relieve the pain? Does anything aggravate the pain? Ask the patient about associated symptoms. Sudden, severe chest pain requires prompt evaluation and treatment because it may herald a life-threatening disorder. (See Managing Severe Chest Pain, pages 154 and 155.)

History and Physical Examination

If the chest pain isn’t severe, proceed with the history. Ask if the patient feels diffuse pain or can point to the painful area. Sometimes a patient won’t perceive the sensation he’s feeling as pain, so ask whether he has any discomfort radiating to his neck, jaw, arms, or back. If he does, ask him to describe it. Is it a dull, aching, pressure-like sensation? Is it a sharp, stabbing, knifelike pain? Does he feel it on the surface or deep inside? Find out whether it’s constant or intermittent. If it’s intermittent, how long does it last? Ask if movement, exertion, breathing, position changes, or eating certain foods worsens or helps relieve the pain. Does anything in particular seem to bring it on?

Review the patient’s history for cardiac or pulmonary disease, chest trauma, intestinal disease, or sickle cell anemia. Find out which medications he’s taking, if any, and ask about recent dosage or schedule changes.

Take the patient’s vital signs, noting tachypnea, fever, tachycardia, oxygen saturation, paradoxical pulse, and hypertension or hypotension. Also, look for jugular vein distention and peripheral edema.

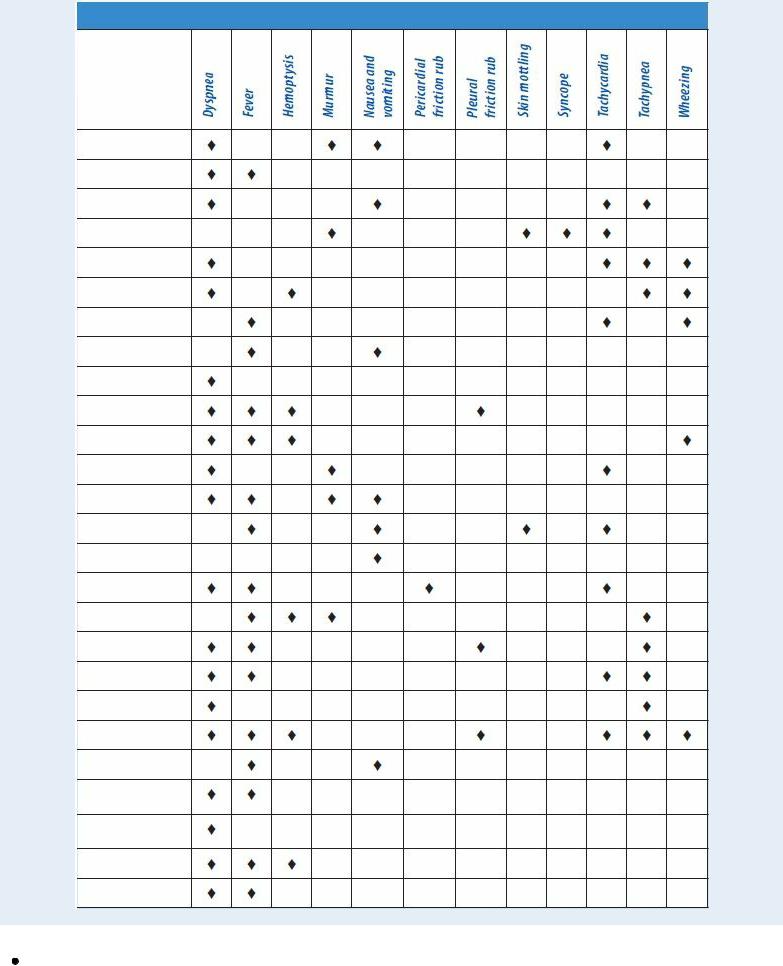

Observe the patient’s breathing pattern, and inspect his chest for asymmetrical expansion. Auscultate his lungs for pleural friction rub, crackles, rhonchi, wheezing, or diminished or absent breath sounds. Next, auscultate for murmurs, clicks, gallops, or pericardial friction rubs. Palpate for lifts, heaves, thrills, gallops, tactile fremitus, and abdominal masses or tenderness. (See Chest Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 156 and 157.)

Medical Causes

Angina pectoris. With angina pectoris, the patient may experience a feeling of tightness or pressure in the chest that he describes as pain or a sensation of indigestion or expansion. The pain usually occurs in the retrosternal region over a palm-sized or larger area. It may radiate to the neck, jaw, and arms — classically, to the inner aspect of the left arm. Angina tends to begin gradually, build to its maximum, and then slowly subside. Provoked by exertion, emotional stress, or a heavy meal, the pain typically lasts 2 to 10 minutes (usually no longer than 20 minutes). Associated findings include dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, dizziness, diaphoresis, belching, and palpitations. You may hear an atrial gallop (a fourth heart sound) or murmur during an anginal episode.

With Prinzmetal’s angina, caused by vasospasm of coronary vessels, chest pain typically occurs when the patient is at rest — or it may awaken him. It may be accompanied by shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and palpitations. During an attack, you may hear an atrial gallop.

Anthrax (inhalation). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease that’s caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Although the disease most commonly occurs in wild and domestic grazing animals, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, the spores can live in the soil for many years. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Most natural cases occur in agricultural regions worldwide. Anthrax may occur in a cutaneous, inhalation, or GI form.

Inhalation anthrax is caused by inhalation of aerosolized spores. Initial signs and symptoms are flulike and include a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain. The disease generally occurs in two stages with a period of recovery after the initial signs and symptoms. The second stage develops abruptly with rapid deterioration marked by a fever, dyspnea, stridor, and hypotension, generally leading to death within 24 hours. Radiologic findings include mediastinitis and symmetric mediastinal widening.

Managing Severe Chest Pain

Sudden, severe chest pain may result from any one of several life-threatening disorders. Your evaluation and interventions will vary, depending on the pain’s location and character. This flowchart will help you establish priorities for managing this emergency successfully.

Chest Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Anxiety. Acute anxiety — or, more commonly, panic attacks — can produce intermittent, sharp, stabbing pain, commonly located behind the left breast. This pain isn’t related to exertion and lasts only a few seconds, but the patient may experience a precordial ache or a sensation of heaviness that lasts for hours or days. Associated signs and symptoms include precordial

tenderness, palpitations, fatigue, a headache, insomnia, breathlessness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and tremors. Panic attacks may be associated with catastrophic events or agoraphobia

— the fear of leaving home or being in open places with other people.

Aortic aneurysm (dissecting). The chest pain associated with a dissecting aortic aneurysm usually begins suddenly and is most severe at its onset. The patient describes an excruciating tearing, ripping, stabbing pain in his chest and neck that radiates to his upper back, abdomen, and lower back. He may also have abdominal tenderness, a palpable abdominal mass, tachycardia, murmurs, syncope, blindness, loss of consciousness, weakness or transient paralysis of the arms or legs, a systolic bruit, systemic hypotension, asymmetrical brachial pulses, a lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, and weak or absent femoral or pedal pulses. His skin is pale, cool, diaphoretic, and mottled below the waist. Capillary refill time is increased in the toes, and palpation may reveal decreased pulsation in one or both carotid arteries.

Asthma. In a life-threatening asthma attack, diffuse and painful chest tightness arises suddenly along with a dry cough and mild wheezing, which progress to a productive cough, audible wheezing, and severe dyspnea. Related respiratory findings include rhonchi, crackles, prolonged expirations, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions on inspiration, accessory muscle use, flaring nostrils, and tachypnea. The patient may also experience anxiety, tachycardia, diaphoresis, flushing, and cyanosis.

Blast lung injury. Resulting from a gust wave after a high explosion discharges upon the body, blast lung injury causes severe chest pain, skin tears, contusions, edema, and hemorrhage of the lungs. Associated respiratory findings include dyspnea, hemoptysis, cough, tachypnea, hypoxia, wheezing, apnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and hemodynamic instability. Global acts of terrorism have increased the incidence of this condition. Chest X-rays, arterial blood gas measurements, computerized tomography scans, and Doppler technology are common diagnostic tools. There are no definitive guidelines for caring for those with blast lung injury; treatment is based on the nature of the explosion, the environment in which it occurred, and any chemical or biological agents involved.

Bronchitis. In its acute form, bronchitis produces a burning chest pain or a sensation of substernal tightness. It also produces a cough, initially dry but later productive, that worsens the chest pain. Other findings include a low-grade fever, chills, a sore throat, tachycardia, muscle and back pain, rhonchi, crackles, and wheezing. Severe bronchitis causes a fever of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C) and possible bronchospasm with worsening wheezing and increased coughing.

Cholecystitis. Cholecystitis typically produces abrupt epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, which may be sharp or intensely aching. Steady or intermittent pain may radiate to the back or right shoulder. Commonly associated findings include nausea, vomiting, a fever, diaphoresis, and chills. Palpation of the right upper quadrant may reveal an abdominal mass, rigidity, distention, or tenderness. Murphy’s sign — inspiratory arrest elicited when the examiner palpates the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep breath — may also occur.

Interstitial lung disease. As interstitial lung disease advances, the patient may experience pleuritic chest pain along with progressive dyspnea, cellophane-type crackles, a nonproductive cough, fatigue, weight loss, decreased exercise tolerance, clubbing, and cyanosis.

Lung abscess. Pleuritic chest pain develops insidiously in lung abscess along with a pleural friction rub and a cough that raises copious amounts of purulent, foul-smelling, blood-tinged sputum. The affected side is dull to percussion, and decreased breath sounds and crackles may

be heard. The patient also displays diaphoresis, anorexia, weight loss, a fever, chills, fatigue, weakness, dyspnea, and clubbing.

Lung cancer. The chest pain associated with lung cancer is commonly described as an intermittent aching felt deep within the chest. If the tumor metastasizes to the ribs or vertebrae, the pain becomes localized, continuous, and gnawing. Associated findings include cough (sometimes bloody), wheezing, dyspnea, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and a fever.

Mitral valve prolapse. Most patients with mitral valve prolapse are asymptomatic, but some may experience sharp, stabbing precordial chest pain or precordial ache. The pain can last for seconds or for hours and occasionally mimics the pain of ischemic heart disease. The characteristic sign of mitral prolapse is a midsystolic click followed by a systolic murmur at the apex. Patients may experience cardiac awareness, a migraine headache, dizziness, weakness, episodic severe fatigue, dyspnea, tachycardia, mood swings, and palpitations.

Myocardial infarction (MI). The chest pain during an MI lasts from 15 minutes to hours. Typically a crushing substernal pain unrelieved by rest or nitroglycerin, it may radiate to the patient’s left arm, jaw, neck, or shoulder blades. Other findings include pallor, clammy skin, dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, restlessness, a feeling of impending doom, hypotension or hypertension, an atrial gallop, murmurs, and crackles.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Chest pain in perimenopausal women may be difficult to diagnose because it may be atypical. Fatigue, nausea, dyspnea, and shoulder or neck pain are symptoms more likely to signal an MI in women than in men.

Pancreatitis. In the acute form, pancreatitis usually causes intense pain in the epigastric area that radiates to the back and worsens when the patient is in a supine position. Nausea, vomiting, a fever, abdominal tenderness and rigidity, diminished bowel sounds, and crackles at the lung bases may also occur. A patient with severe pancreatitis may be extremely restless and have mottled skin, tachycardia, and cold, sweaty extremities. Fulminant pancreatitis causes massive hemorrhage, resulting in shock and coma.

Peptic ulcer. With a peptic ulcer, sharp and burning pain usually arises in the epigastric region. This pain characteristically arises hours after food intake, commonly during the night. It lasts longer than angina-like pain and is relieved by food or an antacid. Other findings include nausea, vomiting (sometimes with blood), melena, and epigastric tenderness.

Pericarditis. Pericarditis produces precordial or retrosternal pain aggravated by deep breathing, coughing, position changes, and occasionally swallowing. The pain is commonly sharp or cutting and radiates to the shoulder and neck. Associated signs and symptoms include a pericardial friction rub, a fever, tachycardia, and dyspnea. Pericarditis usually follows a viral illness, but several other causes should be considered.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). Plague is one of the most virulent bacterial infections and, if untreated, one of the most potentially lethal diseases known. Most cases are sporadic, but the potential for epidemic spread still exists. Clinical forms include bubonic (the most common), septicemic, and pneumonic plagues. The bubonic form is transmitted to a human when bitten by an infected flea. Signs and symptoms include fever, chills, and swollen, inflamed, and tender