Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

encephalopathy, the comatose stage, as the patient’s condition deteriorates. Additional signs include hyperactive reflexes, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and fetor hepaticus. Other symptoms

— disorientation, slurred speech, forgetfulness, tremors, asterixis, lethargy, stupor, and hyperventilation — occur during earlier stages.

Hypoglycemic encephalopathy. Characterized by extremely low blood glucose levels, hypoglycemic encephalopathy may produce decerebrate posture and coma. It also causes dilated pupils, slow respirations, and bradycardia. Muscle spasms, twitching, and seizures eventually progress to flaccidity.

Hypoxic encephalopathy. Severe hypoxia may produce decerebrate posture — the result of brain stem compression associated with anaerobic metabolism and increased ICP. Other findings include coma, a positive Babinski’s reflex, an absence of doll’s eye sign, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes and, possibly, fixed pupils and respiratory arrest.

Pontine hemorrhage. Typically, pontine hemorrhage, a life-threatening disorder, rapidly leads to decerebrate posture with coma. Accompanying signs include total paralysis, the absence of doll’s eye sign, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and small, reactive pupils.

Posterior fossa hemorrhage. Posterior fossa hemorrhage is a subtentorial lesion that causes decerebrate posture. Its early signs and symptoms include vomiting, a headache, vertigo, ataxia, a stiff neck, drowsiness, papilledema, and cranial nerve palsies. The patient eventually slips into coma and may experience respiratory arrest.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Relief from high ICP by removing spinal fluid during a lumbar puncture may precipitate cerebral compression of the brain stem and cause decerebrate posture and coma.

Special Considerations

Help prepare the patient and his family for diagnostic tests that will determine the cause of his decerebrate posture. Diagnostic tests include skull X-rays, a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, cerebral angiography, digital subtraction angiography, EEG, a brain scan, and ICP monitoring.

Monitor the patient’s neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes or as indicated. Also, be alert for signs of increased ICP (bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and a widening pulse pressure) and neurologic deterioration (an altered respiratory pattern and abnormal temperature).

Inform the patient’s family that decerebrate posture is a reflex response — not a voluntary response to pain or a sign of recovery. Offer emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain that decerebrate posture is a reflex response. Provide emotional support to the patient and his family.

Pediatric Pointers

Children younger than age 2 may not display decerebrate posture because the nervous system is still

immature. However, if the posture occurs, it’s usually the more severe opisthotonos. In fact, opisthotonos is more common in infants and young children than in adults and is usually a terminal sign. In children, the most common cause of decerebrate posture is head injury. It also occurs with Reye’s syndrome — the result of increased ICP causing brain stem compression.

REFERENCES

Goswami, R. P. , Mukherjee, A. , Biswas, T. , Karmakar, P. S. , & Ghosh, A. (2012) . Two cases of dengue meningitis: A rare first presentation. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 6(2), 208–211.

Yildizdas, D., Kendirli, T., Arslanköylü, A. E. Horoz, O. O., Incecik, F., … Ince, E., (2011) . Neurological complications of pandemic influenza (H1N1) in children. European Journal of Pediatrics, 170(6), 779–788.

Decorticate Posture

(See Also Decerebrate Posture) [Decorticate rigidity, abnormal flexor response]

A sign of corticospinal tract damage, decorticate posture is characterized by adduction of the arms and flexion of the elbows, with wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are extended and internally rotated, with plantar flexion of the feet. This posture may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. It usually results from stroke or head injury. It may be elicited by noxious stimuli or may occur spontaneously. The intensity of the required stimulus, the duration of the posture, and the frequency of spontaneous episodes vary with the severity and location of cerebral injury.

Although a serious sign, decorticate posture carries a more favorable prognosis than decerebrate posture. However, if the causative disorder extends lower in the brain stem, decorticate posture may progress to decerebrate posture. (See Comparing Decerebrate and Decorticate Postures, page 216.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Obtain the patient's vital signs, and evaluate his level of consciousness (LOC). If his consciousness is impaired, insert an oropharyngeal airway, and take measures to prevent aspiration (unless spinal cord injury is suspected). Evaluate the patient's respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth. Prepare to assist respirations with a handheld resuscitation bag or with intubation and mechanical ventilation, if necessary. Institute seizure precautions.

History and Physical Examination

Test the patient’s motor and sensory functions. Evaluate pupil size, equality, and response to light. Then, test cranial nerve function and deep tendon reflexes. Ask about headache, dizziness, nausea, changes in vision, and numbness or tingling. When did the patient first notice these symptoms? Is his family aware of behavioral changes? Also, ask about a history of cerebrovascular disease, cancer, meningitis, encephalitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bleeding or clotting disorders, or recent trauma.

Medical Causes

Brain abscess. Decorticate posture may occur with brain abscess. Accompanying findings vary depending on the size and location of the abscess, but may include aphasia, hemiparesis, a headache, dizziness, seizures, nausea, and vomiting. The patient may also experience behavioral changes, altered vital signs, and a decreased LOC.

Brain tumor. A brain tumor may produce decorticate posture that’s usually bilateral — the result of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) associated with tumor growth. Related signs and symptoms include a headache, behavioral changes, memory loss, diplopia, blurred vision or vision loss, seizures, ataxia, dizziness, apraxia, aphasia, paresis, sensory loss, paresthesia, vomiting, papilledema, and signs of hormonal imbalance.

Head injury. Decorticate posture may be among the variable features of a head injury, depending on the site and severity of the injury. Associated signs and symptoms include a headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, irritability, a decreased LOC, aphasia, hemiparesis, unilateral numbness, seizures, and pupillary dilation.

Intracerebral hemorrhage. Decorticate posturing can occur within hours in a patient who is diagnosed with an intracerebral hemorrhage, a life-threatening disorder that also produces a rapid, steady loss of consciousness. Associated symptoms can include a severe headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Clinical findings may include increased blood pressure, irregular respirations, Babinski’s reflex, seizures, aphasia, hemiplegia, decerebrate posture, and dilated pupils.

Stroke. Typically, a stroke involving the cerebral cortex produces unilateral decorticate posture, also called spastic hemiplegia. Other signs and symptoms include hemiplegia (contralateral to the lesion), dysarthria, dysphagia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, memory loss, a decreased LOC, urine retention, urinary incontinence, and constipation. Ocular effects include homonymous hemianopsia, diplopia, and blurred vision.

Special Considerations

Assess the patient frequently to detect subtle signs of neurologic deterioration. Also, monitor his neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes to 2 hours. Be alert for signs of increased ICP, including bradycardia, an increasing systolic blood pressure, and a widening pulse pressure.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms of decreased LOC and seizures. Explain to the caregiver how to keep the patient safe, especially during a seizure. Discuss any quality-of-life concerns, and provide needed referrals.

Pediatric Pointers

Decorticate posture is an unreliable sign before age 2 because of nervous system immaturity. In children, this posture usually results from head injury. It also occurs with Reye’s syndrome.

REFERENCES

Miller, L., Arakaki, L., & Ramautar, A . (2014). Elevated risk for invasive meningococcal disease among persons with HIV. Annals of

Internal Medicine, 160(1): 30–37.

Waknine, Y. Meningococcal disease risk 10-fold higher in people with HIV. Medscape Medical News [serial online]. October 30, 2013; Accessed November 13, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/813519.

Deep Tendon Reflexes, Hyperactive

A hyperactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally brisk muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of insertion. This elicited sign may be graded as brisk or pathologically hyperactive. Hyperactive DTRs are commonly accompanied by clonus.

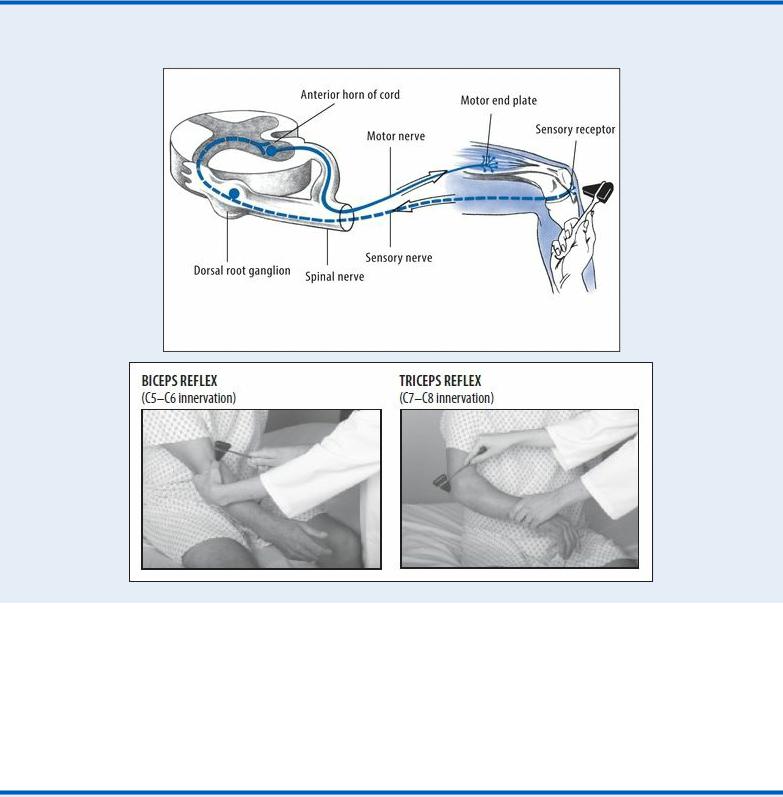

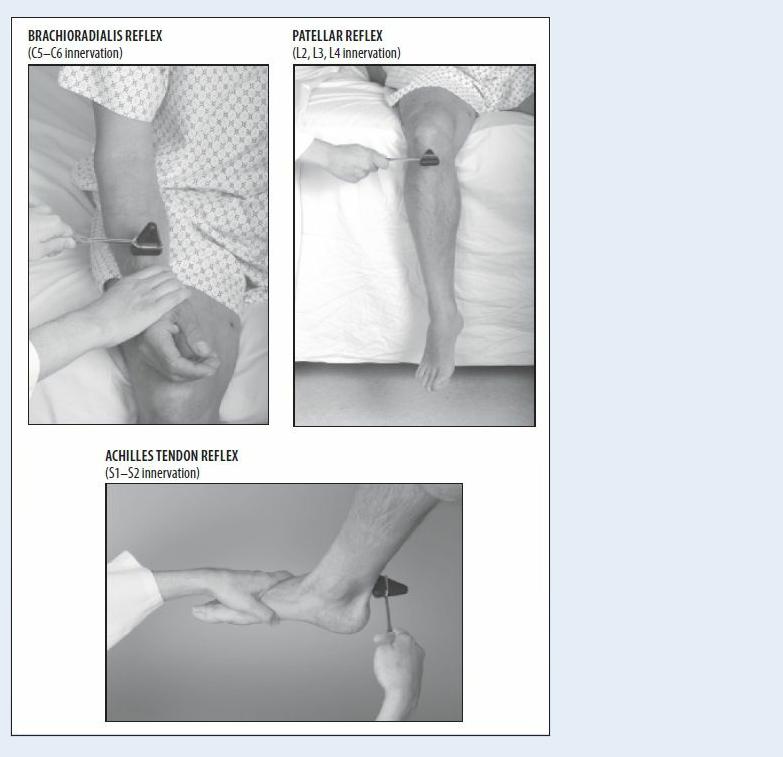

Understanding the Reflex Arc

The corticospinal tract and other descending tracts govern the reflex arc — the relay cycle that produces any reflex response. A corticospinal lesion above the level of the reflex arc being tested may result in hyperactive DTRs. Abnormal neuromuscular transmission at the end of the reflex arc may also cause hyperactive DTRs. For example, a calcium or magnesium deficiency may cause hyperactive DTRs because these electrolytes regulate neuromuscular excitability. (See

Understanding the Reflex Arc.)

Although hyperactive DTRs typically accompany other neurologic findings, they usually lack specific diagnostic value. For example, they’re an early, cardinal sign of hypocalcemia.

History and Physical Examination

After eliciting hyperactive DTRs, take the patient’s history. Ask about spinal cord injury or other trauma and about prolonged exposure to cold, wind, or water. Could the patient be pregnant? A positive response to any of these questions requires prompt evaluation to rule out life-threatening autonomic hyperreflexia, tetanus, preeclampsia, or hypothermia. Ask about the onset and progression of associated signs and symptoms. Next, perform a neurologic examination. Evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness, and test motor and sensory function in the limbs. Ask about paresthesia. Check for ataxia or tremors and for speech and visual deficits. Test for Chvostek’s (an abnormal

spasm of the facial muscles elicited by light taps on the facial nerve in a patient who has hypocalcemia) and Trousseau’s (a carpal spasm induced by inflating a sphygmomanometer cuff on the upper arm to a pressure exceeding systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes in a patient who has hypocalcemia or hypomagnesemia) signs and for carpopedal spasm. Ask about vomiting or altered bladder habits. Make sure to take the patient’s vital signs.

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS produces generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by weakness of the hands and forearms and spasticity of the legs. Eventually, the patient develops atrophy of the neck and tongue muscles, fasciculations, weakness of the legs and, possibly, bulbar signs (dysphagia, dysphonia, facial weakness, and dyspnea).

Brain tumor. A cerebral tumor causes hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms develop slowly and may include unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

Hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia may produce a sudden or gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs with paresthesia, muscle twitching and cramping, positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs, carpopedal spasm, and tetany.

Hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia results in the gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by muscle cramps, hypotension, tachycardia, paresthesia, ataxia, tetany and, possibly, seizures.

Hypothermia. Mild hypothermia (90°F to 94°F [32.2°C to 34.4°C]) produces generalized hyperactive DTRs. Other signs and symptoms include shivering, fatigue, weakness, lethargy, slurred speech, ataxia, muscle stiffness, tachycardia, diuresis, bradypnea, hypotension, and cold, pale skin.

Preeclampsia. Occurring in pregnancy of at least 20 weeks’ gestation, preeclampsia may cause a gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs. Accompanying signs and symptoms include increased blood pressure; abnormal weight gain; edema of the face, fingers, and abdomen after bed rest; albuminuria; oliguria; a severe headache; blurred or double vision; epigastric pain; nausea and vomiting; irritability; cyanosis; shortness of breath; and crackles. If preeclampsia progresses to eclampsia, the patient develops seizures.

Spinal cord lesion. Incomplete spinal cord lesions cause hyperactive DTRs below the level of the lesion. In a traumatic lesion, hyperactive DTRs follow resolution of spinal shock. In a neoplastic lesion, hyperactive DTRs gradually replace normal DTRs. Other signs and symptoms are paralysis and sensory loss below the level of the lesion, urine retention and overflow incontinence, and alternating constipation and diarrhea. A lesion above T6 may also produce autonomic hyperreflexia with diaphoresis and flushing above the level of the lesion, a headache, nasal congestion, nausea, increased blood pressure, and bradycardia.

Stroke. A stroke that affects the origin of the corticospinal tracts causes the sudden onset of hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. The patient may also have unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

Tetanus. With tetanus, the sudden onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanies tachycardia, diaphoresis, a low-grade fever, painful and involuntary muscle contractions, trismus (lockjaw), and risus sardonicus (a masklike grin).

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to evaluate hyperactive DTRs. These may include laboratory tests for serum calcium, magnesium, and ammonia levels, spinal X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, a computed tomography scan, lumbar puncture, and myelography.

If motor weakness accompanies hyperactive DTRs, perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises to preserve muscle integrity and prevent deep vein thrombosis. Also, reposition the patient frequently, provide a special mattress, massage his back, and ensure adequate nutrition to prevent skin breakdown. Administer a muscle relaxant and sedative to relieve severe muscle contractions. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment on hand. Provide a quiet, calm atmosphere to decrease neuromuscular excitability. Assist with activities of daily living, and provide emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain to the caregiver the procedures and treatments the patient may need. Discuss safety measures, and provide emotional support.

Pediatric Pointers

Hyperreflexia may be a normal sign in neonates. After age 6, reflex responses are similar to those of adults. When testing DTRs in small children, use distraction techniques to promote reliable results.

Cerebral palsy commonly causes hyperactive DTRs in children. Reye’s syndrome causes generalized hyperactive DTRs in stage II; in stage V, DTRs are absent. Adult causes of hyperactive DTRs may also appear in children.

REFERENCES

Kluding, P. M. , Dunning, K., O’Dell, M. W. , Wu, S. S., Ginosin, J., Feld, J., & McBride, K. (2013). Foot drop stimulation versus ankle foot orthosis after stroke: 30-week outcomes. Stroke, 44(6), 1660–1669.

Ring, H., Treger, I ., Gruendlinger, L., & Hausdorff, J. M. (2009). Neuroprosthesis for foot drop compared with an ankle-foot orthosis: Effects on postural control during walking. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease, 18(1), 41–47.

Deep Tendon Reflexes, Hypoactive

A hypoactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally diminished muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of insertion. It may be graded as minimal (+) or absent (0). Symmetrically reduced (+) reflexes may be normal.

Normally, a DTR depends on an intact receptor, an intact sensory-motor nerve fiber, an intact neuromuscular-glandular junction, and a functional synapse in the spinal cord. Hypoactive DTRs may result from damage to the reflex arc involving the specific muscle, the peripheral nerve, the nerve roots, or the spinal cord at that level. Hypoactive DTRs are an important sign of many disorders, especially when they appear with other neurologic signs and symptoms. (See Documenting Deep Tendon Reflexes.)

History and Physical Examination

After eliciting hypoactive DTRs, obtain a thorough history from the patient or a family member. Have him describe current signs and symptoms in detail. Then, take a family and drug history.

Next, evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness. Test motor function in his limbs, and palpate for muscle atrophy or increased mass. Test sensory function, including pain, touch, temperature, and vibration sense. Ask about paresthesia. To observe gait and coordination, have the patient take several steps. To check for Romberg’s sign, ask him to stand with his feet together and his eyes closed. During conversation, evaluate speech. Check for signs of vision or hearing loss. Abrupt onset of hypoactive DTRs accompanied by muscle weakness may occur with life-threatening GuillainBarré syndrome, botulism, or spinal cord lesions with spinal shock.

Look for autonomic nervous system effects by taking vital signs and monitoring for increased heart rate and blood pressure. Also, inspect the skin for pallor, dryness, flushing, or diaphoresis. Auscultate for hypoactive bowel sounds, and palpate for bladder distention. Ask about nausea, vomiting, constipation, and incontinence.

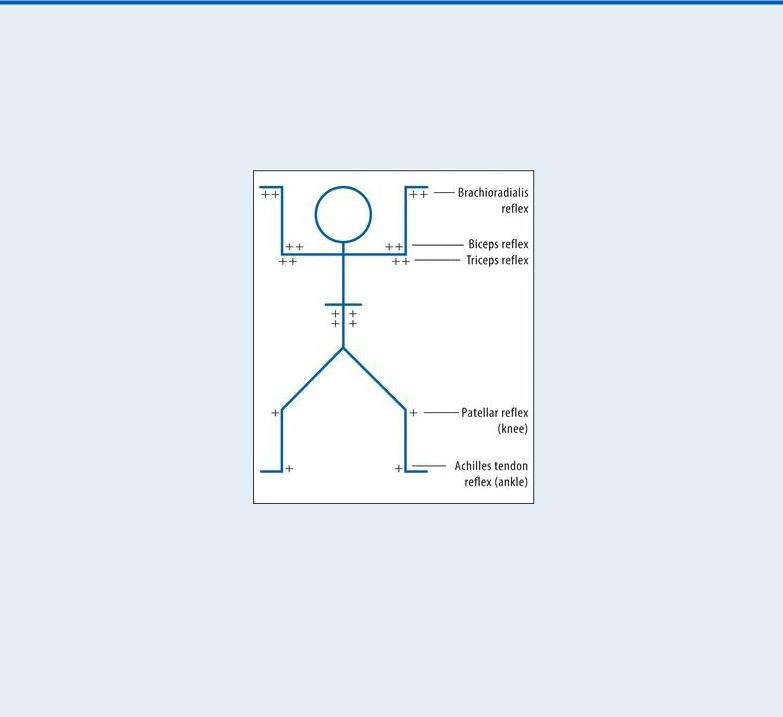

Documenting Deep Tendon Reflexes

Record the patient's deep tendon reflex (DTR) scores by drawing a stick figure and entering the grades on this scale at the proper location. The figure shown here indicates hypoactive DTRs in the legs; other reflexes are normal.

KEY:

0 = absent

+ = hypoactive (diminished) ++ = normal

+++ = brisk (increased)

++++ = hyperactive (clonus may be present)

Medical Causes

Botulism. With botulism, generalized hypoactive DTRs accompany progressive descending muscle weakness. Initially, the patient usually complains of blurred and double vision and, occasionally, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Other early bulbar findings include vertigo, hearing loss, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The patient may have signs of respiratory distress and severe constipation marked by hypoactive bowel sounds.

Eaton-Lambert syndrome. Eaton-Lambert syndrome produces generalized hypoactive DTRs. Early signs include difficulty rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and walking. The patient may complain of achiness, paresthesia, and muscle weakness that’s most severe in the morning. Weakness improves with mild exercise and worsens with strenuous exercise.

Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome causes bilateral hypoactive DTRs that progress rapidly from hypotonia to areflexia in several days. This disorder typically causes muscle weakness that begins in the legs and then extends to the arms and, possibly, to the trunk and neck muscles. Occasionally, weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other signs and symptoms include cranial nerve palsies, pain, paresthesia, and signs of brief autonomic dysfunction, such as sinus tachycardia or bradycardia, flushing, fluctuating blood pressure, and anhidrosis or episodic diaphoresis.

Usually, muscle weakness and hypoactive DTRs peak in severity within 10 to 14 days, and then, symptoms begin to clear. However, in severe cases, residual hypoactive DTRs and motor weakness may persist.

Peripheral neuropathy. Characteristic of end-stage diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and alcoholism and as an adverse effect of various medications, peripheral neuropathy results in progressive hypoactive DTRs. Other effects include motor weakness, sensory loss, paresthesia, tremors, and possible autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic hypotension and incontinence.

Polymyositis. With polymyositis, hypoactive DTRs accompany muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, spasms and, possibly, increased size or atrophy. These effects are usually temporary; their location varies with the affected muscles.

Spinal cord lesions. Spinal cord injury or complete transection produces spinal shock, resulting in hypoactive DTRs (areflexia) below the level of the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms include quadriplegia or paraplegia, flaccidity, a loss of sensation below the level of the lesion, and dry, pale skin. Also characteristic are urine retention with overflow incontinence, hypoactive bowel sounds, constipation, and genital reflex loss. Hypoactive DTRs and flaccidity are usually transient; reflex activity may return within several weeks.

Syringomyelia. Permanent bilateral hypoactive DTRs occur early in syringomyelia, which is a slowly progressive disorder. Other signs and symptoms include muscle weakness and atrophy; loss of sensation, usually extending in a capelike fashion over the arms, shoulders, neck, back, and occasionally the legs; deep, boring pain (despite analgesia) in the limbs; and signs of brain stem involvement (nystagmus, facial numbness, unilateral vocal cord paralysis or weakness, and unilateral tongue atrophy). It’s more common in males than in females.

Other Causes

Drugs. Barbiturates and paralyzing drugs, such as pancuronium and curare, may cause

hypoactive DTRs.

Special Considerations

Help the patient perform his daily activities. Try to strike a balance between promoting independence and ensuring his safety. Encourage him to walk with assistance. Make sure personal care articles are within easy reach, and provide an obstacle-free course from his bed to the bathroom.

If the patient has sensory deficits, protect him from injury from heat, cold, or pressure. Test his bath water, and reposition him frequently, ensuring a soft, smooth bed surface. Keep his skin clean and dry to prevent breakdown. Perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises. Also, encourage a balanced diet with plenty of protein and adequate hydration.

Patient Counseling

Teach skills that can help with independence in daily life. Discuss safety measures, including walking with assistance.

Pediatric Pointers

Hypoactive DTRs commonly occur in patients with muscular dystrophy, Friedreich’s ataxia, syringomyelia, and spinal cord injury. They also accompany progressive muscular atrophy, which affects preschoolers and adolescents.

Use distraction techniques to test DTRs; assess motor function by watching the infant or child at play.

REFERENCES

Born-Frontsberg, E. , Reincke, M. , Rump, L. C., Hahner, S. , Diederich, S. , Lorenz, R., … Quinkler, M. ; Participants of the German Conn’s Registry. (2009). Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidities of hypokalemic and normokalemic primary aldosteronism: Results of the German Conn’s Registry. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 94(4), 1125–1130.

Krantz, M. J., Martin, J., Stimmel, B., Mehta, D., & Haigney, M. C. (2009). QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150, 387–395.

Depression

Depression is a mood disturbance characterized by feelings of sadness, despair, and loss of interest or pleasure in activities. These feelings may be accompanied by somatic complaints, such as changes in appetite, sleep disturbances, restlessness or lethargy, and decreased concentration. Thoughts of injuring one’s self, death, or suicide may also occur.

Clinical depression must be distinguished from “the blues,” periodic bouts of dysphoria that are less persistent and severe than the clinical disorder. The criterion for major depression is one or more episodes of depressed mood, or decreased interest or the ability to take pleasure in all or most activities, lasting at least 2 weeks.

Major depression affects approximately 20.9 million (9.5%) Americans in a given year. Approximately 12 million women (12%), 6 million men (7%), and 3 million adolescents (4%) experience depression each year. It affects all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, and it is twice as common in women as in men. It is the leading cause of disability of women and men of all ages in the United States and worldwide. Depression has numerous causes, including genetic and