Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

24 to 48 hours after exposure, then resolve; if severe, however, they may recur 2 to 5 weeks later.

Common cold. When the common cold causes productive coughing, the sputum is mucoid or mucopurulent. Early indications include a dry hacking cough, sneezing, a headache, malaise, fatigue, rhinorrhea (watery to tenacious, mucopurulent secretions), nasal congestion, a sore throat, myalgia, and arthralgia.

Lung abscess (ruptured). The cardinal sign of a ruptured lung abscess is coughing that produces copious amounts of purulent, foul-smelling, and possibly blood-tinged sputum. A ruptured abscess can also cause diaphoresis, anorexia, clubbing, weight loss, weakness, fatigue, a fever with chills, dyspnea, a headache, malaise, pleuritic chest pain, halitosis, inspiratory crackles, and tubular or amphoric breath sounds. The patient’s chest is dull on percussion on the affected side.

Lung cancer. One of the earliest signs of bronchogenic carcinoma is a chronic cough that produces small amounts of purulent (or mucopurulent), blood-streaked sputum. In a patient with bronchoalveolar cancer, however, coughing produces large amounts of frothy sputum. Other signs and symptoms include dyspnea, anorexia, fatigue, weight loss, chest pain, a fever, diaphoresis, wheezing, and clubbing.

Nocardiosis. Nocardiosis causes a productive cough (with purulent, thick, tenacious, and possibly blood-tinged sputum) and fever that may last several months. Other findings include night sweats, pleuritic pain, anorexia, malaise, fatigue, weight loss, and diminished or absent breath sounds. The patient’s chest is dull on percussion.

North American blastomycosis. North American blastomycosis is a chronic disorder that produces coughing that’s dry and hacking or produces bloody or purulent sputum. Other findings include pleuritic chest pain, a fever, chills, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, fatigue, night sweats, cutaneous lesions (small, painless, nonpruritic macules or papules), and prostration.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). Plague is one of the most virulent acute bacterial infections and, if untreated, one of the most potentially lethal diseases known. Most cases are sporadic, but the potential for epidemic spread still exists. Clinical forms include bubonic (the most common), septicemic, and pneumonic plagues. The bubonic form is transmitted to a human when bitten by an infected flea. Signs and symptoms occur within 2 to 8 days and include a fever, chills, and swollen, inflamed, and tender lymph nodes near the site of the flea bite. Septicemic plague develops as a fulminant illness generally with the bubonic form. The pneumonic form may be contracted from person to person through breathing in infected airborne droplets or through biological warfare from aerosolization and inhalation of the organism. The onset is usually sudden with chills, a fever, a headache, and myalgia. Pulmonary signs and symptoms include a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

Pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia initially produces a dry cough that becomes productive. Associated signs and symptoms develop suddenly and include shaking chills, a high fever, myalgia, a headache, pleuritic chest pain that increases with chest movement, tachypnea, tachycardia, dyspnea, cyanosis, diaphoresis, decreased breath sounds, fine crackles, and rhonchi.

Mycoplasma pneumonia may cause a cough that produces scant blood-flecked sputum. Typically, however, a nonproductive cough starts 2 to 3 days after the onset of malaise, a headache, a fever, and a sore throat. Paroxysmal coughing causes substernal chest pain. Patients

may develop crackles, but generally don’t appear seriously ill.

Popcorn lung disease. Popcorn lung disease is a term attributed to the type of infection reported among factory workers experiencing respiratory symptoms after inhaling butter-flavoring chemicals such as diacetyl, used in the manufacture of microwave popcorn. Patients typically complain of gradual onset of a productive cough that worsens over time, progressive shortness of breath, and unusual fatigue. Clinical findings include wheezing, chest pain, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Bronchiolitis fibrosa obliterans, an irreversible fixed airway obstructive lung disorder, is the most severe condition reported. Before a diagnosis is conclusive, other causes must be ruled out.

Psittacosis. Psittacosis is a bacterial infection transmitted from birds to humans. As psittacosis progresses, the characteristic hacking cough, nonproductive at first, may later produce a small amount of mucoid, blood-streaked sputum. The infection may begin abruptly, with chills, a fever, a headache, myalgia, and prostration. Other signs and symptoms include tachypnea, fine crackles, chest pain (rare), epistaxis, photophobia, abdominal distention and tenderness, nausea, vomiting, and a faint macular rash. Severe infection may produce stupor, delirium, and coma.

Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis causes a nonproductive or slightly productive cough with a fever, occasional chills, pleuritic chest pain, a sore throat, a headache, backache, malaise, marked weakness, anorexia, hemoptysis, and an itchy macular rash. Rhonchi and wheezing may be heard. The disease may spread to other areas, causing arthralgia, swelling of the knees and ankles, and erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme.

Pulmonary edema. When severe, pulmonary edema, which is a life-threatening disorder, causes a cough that produces frothy, bloody sputum. Early signs and symptoms include exertional dyspnea; paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, followed by orthopnea; and coughing, which may be nonproductive initially. Others include a fever, fatigue, tachycardia, tachypnea, dependent crackles, and a ventricular gallop. As the patient’s respirations become increasingly rapid and labored, he develops more diffuse crackles and a productive cough, worsening tachycardia and, possibly, arrhythmias. His skin becomes cold, clammy, and cyanotic; his blood pressure falls; and his pulse becomes thready.

Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening disorder that causes a cough that may be nonproductive or may produce blood-tinged sputum. Usually, the first symptom of a pulmonary embolism is severe dyspnea, which may be accompanied by angina or pleuritic chest pain. The patient experiences marked anxiety, a low-grade fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and diaphoresis. Less common signs include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema, and, with a large embolus, cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention. The patient may also have a pleural friction rub, diffuse wheezing, crackles, chest dullness on percussion, decreased breath sounds, and signs of circulatory collapse.

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). Pulmonary TB causes a mild to severe productive cough along with some combination of hemoptysis, malaise, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Sputum may be scant and mucoid or copious and purulent. Typically, the patient experiences night sweats, easy fatigability, and weight loss. His breath sounds are amphoric. He may have chest dullness on percussion and, after coughing, increased tactile fremitus with crackles.

Silicosis. A productive cough with mucopurulent sputum is the earliest sign of silicosis. The patient also has exertional dyspnea, tachypnea, weight loss, fatigue, general weakness, and recurrent respiratory infections. Auscultation reveals end-inspiratory, fine crackles at the lung bases.

Tracheobronchitis. Inflammation initially causes a nonproductive cough that later — following the onset of chills, a sore throat, a slight fever, muscle and back pain, and substernal tightness — becomes productive as secretions increase. Sputum is mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent. The patient typically has rhonchi and wheezes; he may also develop crackles. Severe tracheobronchitis may cause a fever of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C) and bronchospasm.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Bronchoscopy and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may increase productive coughing.

Drugs. Expectorants increase productive coughing. These include ammonium chloride, calcium iodide, guaifenesin, iodinated glycerol, potassium iodide, and terpin hydrate.

Respiratory therapy. Intermittent positive-pressure breathing, nebulizer therapy, and incentive spirometry can help loosen secretions and cause or increase productive coughing.

Special Considerations

Avoid taking measures to suppress a productive cough because retention of sputum may interfere with alveolar aeration or impair pulmonary resistance to infection. Expect to give a mucolytic and an expectorant, and increase the patient’s intake of oral fluids to thin his secretions and increase their flow. In addition, you may give a bronchodilator to relieve bronchospasms and open airways. An antibiotic may be ordered to treat an underlying infection.

Humidify the air around the patient; this will relieve mucous membrane inflammation and also help loosen dried secretions. Provide pulmonary physiotherapy, such as postural drainage with vibration and percussion, to loosen secretions. Aerosol therapy may be necessary.

Provide the patient with uninterrupted rest periods. Keep him from using respiratory irritants. If he’s confined to bed rest, change his position often to promote the drainage of secretions.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as chest X-ray, bronchoscopy, a lung scan, and PFTs. Collect sputum samples for culture and sensitivity testing.

Patient Counseling

Refer the patient to resources to quit smoking. Teach the patient and caregiver to use chest percussion to loosen secretions, and teach the patient coughing and deep breathing techniques. Explain infection control techniques and how to avoid respiratory irritants.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a child’s airway is narrow, a productive cough can quickly cause airway occlusion and respiratory distress from thick or excessive secretions. Causes of a productive cough in a child include asthma, bronchiectasis, bronchitis, acute bronchiolitis, cystic fibrosis, and pertussis.

When caring for a child with a productive cough, administer expectorants, but don’t expect to give a cough suppressant. To soothe inflamed mucous membranes and prevent drying of secretions, provide humidified air or oxygen. Remember, high humidity can induce bronchospasm in a hyperactive child or produce overhydration in an infant, and drinking milk can increase the viscosity of secretions.

Geriatric Pointers

Always ask elderly patients about a productive cough because this sign may indicate a serious acute or chronic illness.

REFERENCES

Kumar, K., Guirgis, M., Zieroth, S., Lom, E., Menkis, A. H., Arora, R. C., & Freed, D. H. (2011). Influenza myocarditis and myositis: Case presentation and review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 27, 514–522.

Ukimura, A., Satomi, H., Ooi, Y., & Kanzaki, Y. (2012) . Myocarditis associated with influenza A H1N1 . Influenza Res Treatment , 2012, 351979.

Crackles[Rales, crepitations]

A common finding in patients with certain cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders, crackles are nonmusical clicking or rattling noises heard during auscultation of breath sounds. They usually occur during inspiration and recur constantly from one respiratory cycle to the next. They can be unilateral or bilateral, moist or dry. They’re characterized by their pitch, loudness, location, persistence, and occurrence during the respiratory cycle.

Crackles indicate abnormal movement of air through fluid-filled airways. They can be irregularly dispersed, as in pneumonia, or localized, as in bronchiectasis. (A few basilar crackles can be heard in normal lungs after prolonged shallow breathing. These normal crackles clear with a few deep breaths.) Usually, crackles indicate the degree of an underlying illness. When crackles result from a generalized disorder, they usually occur in the less distended and more dependent areas of the lungs, such as the lung bases, when the patient is standing. Crackles due to air passing through inflammatory exudate may not be audible if the involved portion of the lung isn’t being ventilated because of shallow respirations. (See How Crackles Occur.)

How Crackles Occur

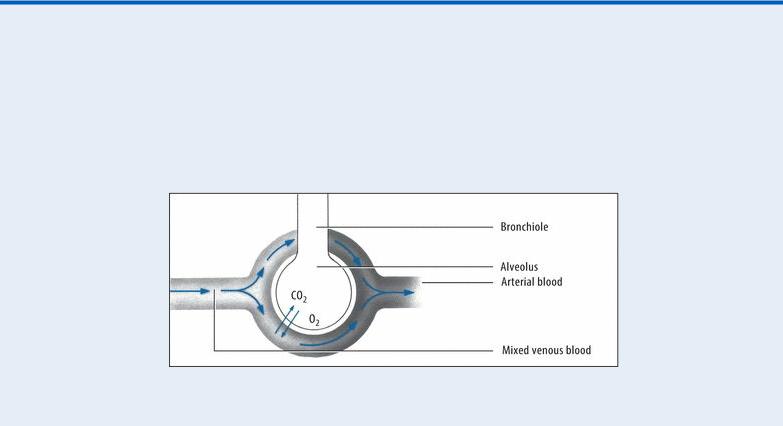

Crackles occur when air passes through fluid-filled airways, causing collapsed alveoli to pop open as the airway pressure equalizes. They can also occur when membranes lining the chest cavity and the lungs become inflamed. The illustrations below show a normal alveolus and two pathologic alveolar changes that cause crackles.

Normal Alveolus

Alveolus in Pulmonary Edema

Alveolus in Inflammation

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Quickly take the patient’s vital signs and examine him for signs of respiratory distress or airway obstruction. Check the depth and rhythm of respirations. Is he struggling to breathe? Check for increased accessory muscle use and chest wall motion, retractions, stridor, or nasal flaring. Assess the patient for other signs and symptoms of fluid overload, such as jugular vein distention and edema. Provide supplemental oxygen and, if necessary, a diuretic. Endotracheal intubation may also be necessary.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient also has a cough, ask when it began and if it’s constant or intermittent. Find out what the cough sounds like and whether he’s coughing up sputum or blood. If the cough is productive, determine the sputum’s consistency, amount, odor, and color.

Ask the patient if he has any pain. If so, where is it located? When did he first notice it? Does it radiate to other areas? Also, ask the patient if movement, coughing, or breathing worsens or helps relieve his pain. Note the patient’s position: Is he lying still or moving about restlessly?

Obtain a brief medical history. Does the patient have cancer or a known respiratory or cardiovascular problem? Ask about recent surgery, trauma, or illness. Does he smoke or drink alcohol? Is he experiencing hoarseness or difficulty swallowing? Find out which medications he’s taking. Also, ask about recent weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, weakness, vertigo, and syncope. Has the patient been exposed to irritants, such as vapors, fumes, or smoke?

Next, perform a physical examination. Examine the patient’s nose and mouth for signs of infection, such as inflammation or increased secretions. Note his breath odor; halitosis could indicate pulmonary infection. Check his neck for masses, tenderness, swelling, lymphadenopathy, or venous distention.

Inspect the patient’s chest for abnormal configuration or uneven expansion. Percuss for dullness, tympany, or flatness. Auscultate his lungs for other abnormal, diminished, or absent breath sounds. Listen to his heart for abnormal sounds, and check his hands and feet for edema or clubbing. (See

Crackles: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

Medical Causes

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is a life-threatening disorder that causes diffuse, fine to coarse crackles usually heard in the dependent portions of the lungs. It also produces cyanosis, nasal flaring, tachypnea, tachycardia, grunting respirations, rhonchi, dyspnea, anxiety, and a decreased level of consciousness.

Bronchiectasis. With bronchiectasis, persistent, coarse crackles are heard over the affected area of the lung. They’re accompanied by a chronic cough that produces copious amounts of mucopurulent sputum. Other characteristics include halitosis, occasional wheezes, exertional dyspnea, rhonchi, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, weakness, a recurrent fever, and late-stage clubbing.

Bronchitis (chronic). Bronchitis causes coarse crackles that are usually heard at the lung bases. Prolonged expirations, wheezing, rhonchi, exertional dyspnea, tachypnea, and a persistent, productive cough occur because of increased bronchial secretions. Clubbing and cyanosis may occur as a late sign.

Crackles: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Legionnaires’ disease. Legionnaires’ disease produces diffuse, moist crackles and a cough that produces scant mucoid, nonpurulent, and possibly blood-streaked sputum. Usually, prodromal signs and symptoms occur, including malaise, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, diffuse myalgia and, possibly, diarrhea. Within 12 to 48 hours, the patient develops a dry cough and a sudden high fever with chills. He may also have pleuritic chest pain, a headache, tachypnea, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, mild temporary amnesia, confusion, flushing, mild diaphoresis, and prostration.

Pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia produces diffuse fine crackles, a sudden onset of shaking chills, a high fever, tachypnea, pleuritic chest pain, cyanosis, grunting respirations, nasal flaring, decreased breath sounds, myalgia, a headache, tachycardia, dyspnea, cyanosis, diaphoresis, and rhonchi. The patient also has a dry cough that later becomes productive.

Mycoplasma pneumonia produces medium to fine crackles together with a nonproductive cough, malaise, a sore throat, a headache, and a fever. The patient may have blood-flecked sputum. Viral pneumonia causes gradually developing, diffuse crackles. The patient may also have a nonproductive cough, malaise, a headache, anorexia, a low-grade fever, and decreased breath sounds.

Pulmonary edema. Moist, bubbling crackles on inspiration are one of the first signs of

pulmonary edema, which is a life-threatening disorder. Other early findings include exertional dyspnea; paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and then orthopnea; and coughing, which may be initially nonproductive but later produces frothy, bloody sputum. Related clinical effects include tachycardia, tachypnea, and a third heart sound (S3 gallop). As the patient’s respirations become increasingly rapid and labored, he develops more diffuse crackles, worsening tachycardia, hypotension, a rapid and thready pulse, cyanosis, and cold, clammy skin.

Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening disorder that can cause fine to coarse crackles and a cough that may be dry or produce blood-tinged sputum. Usually, the first sign of pulmonary embolism is severe dyspnea, which may be accompanied by angina or pleuritic chest pain. The patient has marked anxiety, a low-grade fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and diaphoresis. Less common signs include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema, and, with a large embolus, cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention. The patient may also have a pleural friction rub, diffuse wheezing, chest dullness on percussion, decreased breath sounds, and signs of circulatory collapse.

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). With pulmonary TB, fine crackles occur after coughing. The patient has some combination of hemoptysis, malaise, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Sputum may be scant and mucoid or copious and purulent. Typically, the patient is easily fatigued and experiences night sweats, weakness, and weight loss. His breath sounds are amphoric.

Tracheobronchitis. In its acute form, tracheobronchitis produces moist or coarse crackles along with a productive cough, chills, a sore throat, a slight fever, muscle and back pain, and substernal tightness. The patient typically has rhonchi and wheezes. Severe tracheobronchitis may cause a moderate fever and bronchospasm.

Special Considerations

To keep the patient’s airway patent and facilitate his breathing, elevate the head of his bed. To liquefy thick secretions and relieve mucous membrane inflammation, administer fluids, humidified air, or oxygen. Diuretics may be needed if crackles result from cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Fluid restriction may also be necessary. Turn the patient every 1 to 2 hours, and encourage him to breathe deeply.

Plan daily uninterrupted rest periods to help the patient relax and sleep. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as chest X-rays, a lung scan, and sputum analysis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient effective coughing techniques and to avoid respiratory irritants. Stress the importance of quitting smoking, and refer him to appropriate resources to help him quit.

Pediatric Pointers

Crackles in infants or children may indicate a serious cardiovascular or respiratory disorder. Pneumonias produce diffuse, sudden crackles in children. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula can cause bubbling, moist crackles due to aspiration of food or secretions into the lungs — especially in neonates. Pulmonary edema causes fine crackles at the bases of the lungs, and bronchiectasis produces moist crackles. Cystic fibrosis produces widespread, fine to coarse inspiratory crackles and wheezing in infants. Sickle cell anemia may produce crackles when it causes

pulmonary infarction or infection. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in lower respiratory tract typically produces fine crackles and wheezes.

Geriatric Pointers

Crackles that clear after deep breathing may indicate mild basilar atelectasis. In older patients, auscultate the lung bases before and after auscultating the apices.

REFERENCES

Blanchard, C., & Rothenberg, M. E. (2009). Biology of the eosinophil. Advances in Immunology, 101, 81–121.

Gotlib, J. (2011). World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2011 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management .

American Journal of Hematology, 86(8), 677–688.

Crepitation, Bony[Bony crepitus]

Bony crepitation is a palpable vibration or an audible crunching sound that results when one bone grates against another. This sign commonly results from a fracture, but it can happen when bones that have been stripped of their protective articular cartilage grind against each other as they articulate — for example, in patients with advanced arthritic or degenerative joint disorders.

Eliciting bony crepitation can help confirm the diagnosis of a fracture, but it can also cause further soft tissue, nerve, or vessel injury. Always evaluate distal pulses and perform neurologic checks distal to the suspected fracture site before manipulating an extremity. In addition, rubbing fractured bone ends together can convert a closed fracture into an open one if a bone end penetrates the skin. Therefore, after the initial detection of crepitation in a patient with a fracture, avoid subsequent elicitation of this sign.

History and Physical Examination

If you detect bony crepitation in a patient with a suspected fracture, ask him if he feels pain and if he can point to the painful area. To prevent lacerating nerves, blood vessels, or other structures, immobilize the affected area by applying a splint that includes the joints above and below the affected area. Elevate the affected area, if possible, and apply cold packs. Inspect for abrasions or lacerations. Find out how and when the injury occurred. Palpate pulses distal to the injury site; check the skin for pallor or coolness. Test motor and sensory function distal to the injury site.

If the patient doesn’t have a suspected fracture, ask about a history of osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Which medications does he take? Has any medication helped ease arthritic discomfort? Take the patient’s vital signs and test his joint range of motion (ROM).

Medical Causes

Fracture. In addition to bony crepitation, a fracture causes acute local pain, hematoma, edema, and decreased ROM. Other findings may include deformity, point tenderness, discoloration of the limb, and loss of limb function. Neurovascular damage may cause increased capillary refill time, diminished or absent pulses, mottled cyanosis, paresthesia, and decreased sensation (all distal to the fracture site). An open fracture, of course, produces an obvious skin wound.

Osteoarthritis. In its advanced form, joint crepitation may be elicited during ROM testing. Soft

fine crepitus on palpation may indicate roughening of the articular cartilage; coarse grating may indicate badly damaged cartilage. The cardinal symptom of osteoarthritis is joint pain, especially during motion and weight bearing. Other findings include joint stiffness that typically occurs after resting and subsides within a few minutes after the patient begins moving.

Rheumatoid arthritis. In its advanced form, bony crepitation is heard when the affected joint is rotated. However, rheumatoid arthritis usually develops insidiously, producing nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as fatigue, malaise, anorexia, a persistent low-grade fever, weight loss, and vague arthralgia and myalgia. Later, more specific and localized articular signs develop, commonly at the proximal finger joints. These signs usually occur bilaterally and symmetrically and may extend to the wrists, knees, elbows, and ankles. The affected joints stiffen after inactivity. The patient also has increased warmth, swelling, and tenderness of affected joints as well as limited ROM.

Special Considerations

If a fracture is suspected, prepare the patient for X-rays of the affected area, and reexamine his neurovascular status frequently. Keep the affected part immobilized and elevated until treatment begins. Give an analgesic to relieve pain.

Keep in mind that degenerative joint changes, which have usually begun by age 20 or 30, progress more rapidly after age 40 and occur primarily in weight-bearing joints, such as the lumbar spine, hips, knees, and ankles.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about activity limitation. Show the patient how to use ambulatory aids, such as walkers, canes, and crutches, and how to perform skin and foot care. Discuss the use of proper body mechanics to prevent injury. Encourage the patient to perform activities of daily living as much as possible to maintain independence, muscle strength, and joint ROM. If the patient has a cast, explain proper cast care and when to seek medical attention.

Pediatric Pointers

Bony crepitation in a child usually occurs after a fracture. Obtain an accurate history of the injury, and be alert for the possibility of child abuse. In a teenager, bony crepitation and pain in the patellofemoral joint help diagnose chondromalacia of the patella.

REFERENCES

Chen, C. H. (2009) . Strategies to enhance tendon graft—bone healing in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Chang Gung Medical Journal, 32, 483–493.

Reinhardt, K. R., Hetsroni, I. F., & Marx, R. G. (2010). Graft selection for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a level I systematic review comparing failure rates and functional outcomes. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 41, 249–262.

Crepitation, Subcutaneous[Subcutaneous crepitus, subcutaneous emphysema]

When bubbles of air or other gases (such as carbon dioxide) are trapped in subcutaneous tissue,