Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfCOMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH HERBS

OBTAINING A HEALTH HISTORY

SELECTED REFERENCES

INDEX

A

Abdominal Distention

(See Also Abdominal Mass, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Rigidity)

Abdominal distention refers to increased abdominal girth — the result of increased intraabdominal pressure forcing the abdominal wall outward. Distention may be mild or severe, depending on the amount of pressure. It may be localized or diffuse and may occur gradually or suddenly. Acute abdominal distention may signal life-threatening peritonitis or acute bowel obstruction.

Abdominal distention may result from fat, flatus, a fetus (pregnancy or intra-abdominal mass [ectopic pregnancy]), or fluid. Fluid and gas are normally present in the GI tract but not in the peritoneal cavity. However, if fluid and gas can’t pass freely through the GI tract, abdominal distention occurs. In the peritoneal cavity, distention may reflect acute bleeding, accumulation of ascitic fluid, or air from perforation of an abdominal organ.

Abdominal distention doesn’t always signal pathology. For example, in anxious patients or those with digestive distress, localized distention in the left upper quadrant can result from aerophagia — the unconscious swallowing of air. Generalized distention can result from ingestion of fruits or vegetables with large quantities of unabsorbable carbohydrates, such as legumes, or from abnormal food fermentation by microbes. Don’t forget to rule out pregnancy in all females with abdominal distention.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient displays abdominal distention, quickly check for signs of hypovolemia, such as pallor, diaphoresis, hypotension, a rapid thready pulse, rapid shallow breathing, decreased urine output, and altered mentation. Ask the patient if he’s experiencing severe abdominal pain or difficulty breathing. Find out about any recent accidents, and observe him for signs of trauma and peritoneal bleeding, such as Cullen’s sign or Turner’s sign. Then, auscultate all abdominal quadrants, noting rapid and high-pitched, diminished, or absent bowel sounds. (If you don’t hear bowel sounds immediately, listen for at least 5 minutes in each of the four abdominal quadrants.) Gently palpate the abdomen for rigidity. Remember that deep or extensive palpation may increase pain.

If you detect abdominal distention and rigidity along with abnormal bowel sounds and if the patient complains of pain, begin emergency interventions. Place the patient in the supine position, administer oxygen, and insert an I.V. line for fluid replacement. Prepare to insert a nasogastric tube to relieve acute intraluminal distention. Reassure the patient, and prepare him for surgery.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s abdominal distention isn’t acute, ask about its onset and duration and associated signs. A patient with localized distention may report a sensation of pressure, fullness, or tenderness in the affected area. A patient with generalized distention may report a bloated feeling, a pounding heart, and difficulty breathing deeply or when lying flat. (See Abdominal Distention: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

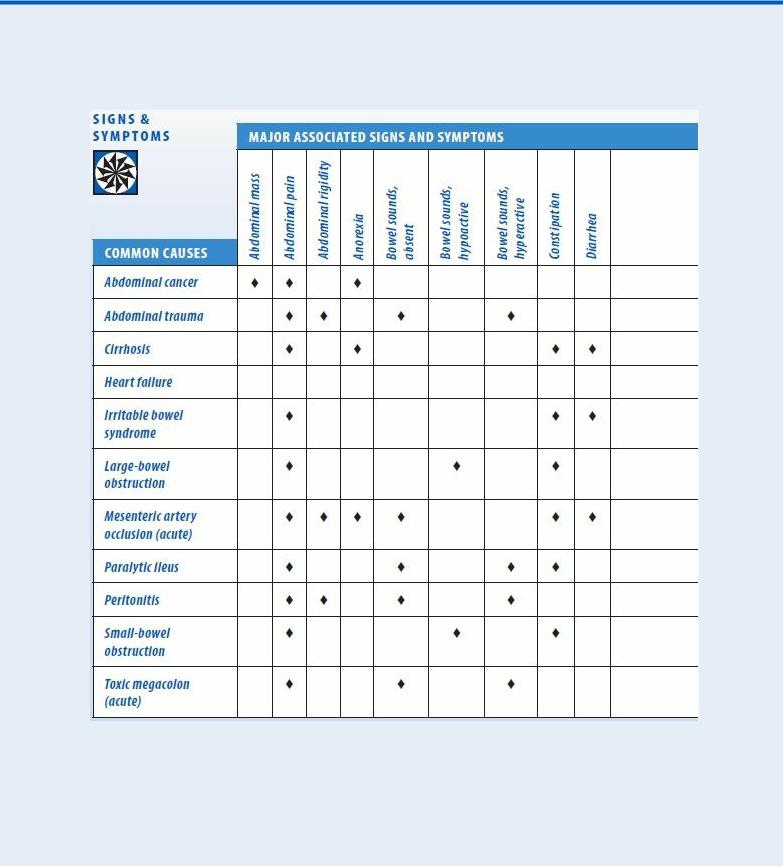

Abdominal Distention: Common Causes and Associated

Findings

The patient may also feel unable to bend at his waist. Make sure to ask about abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, altered bowel habits, and weight gain or loss.

Obtain a medical history, noting GI or biliary disorders that may cause peritonitis or ascites, such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, or inflammatory bowel disease. (See Detecting Ascites, page 4.) Also, note chronic constipation. Has the patient recently had abdominal surgery, which can lead to abdominal distention? Ask about recent accidents, even minor ones, such as falling off a stepladder.

Perform a complete physical examination. Don’t restrict the examination to the abdomen because you could miss important clues to the cause of abdominal distention. Next, stand at the foot of the bed and observe the recumbent patient for abdominal asymmetry to determine if distention is localized or generalized. Then, assess abdominal contour by stooping at his side. Inspect for tense, taut skin and bulging flanks, which may indicate ascites. Observe the umbilicus. An everted umbilicus may indicate ascites or umbilical hernia. An inverted umbilicus may indicate distention from gas; it’s also common in obesity. Inspect the abdomen for signs of inguinal or femoral hernia and for incisions that may point to adhesions. Both may lead to intestinal obstruction. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds, abdominal friction rubs (indicating peritoneal inflammation), and bruits (indicating an aneurysm). Listen for succussion splash — a splashing sound normally heard in the stomach when the patient moves or when palpation disturbs the viscera. However, an abnormally loud splash indicates fluid

accumulation, suggesting gastric dilation or obstruction.

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Ascites

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Ascites

To differentiate ascites from other causes of abdominal distention, check for shifting dullness, fluid wave, and puddle sign, as described here.

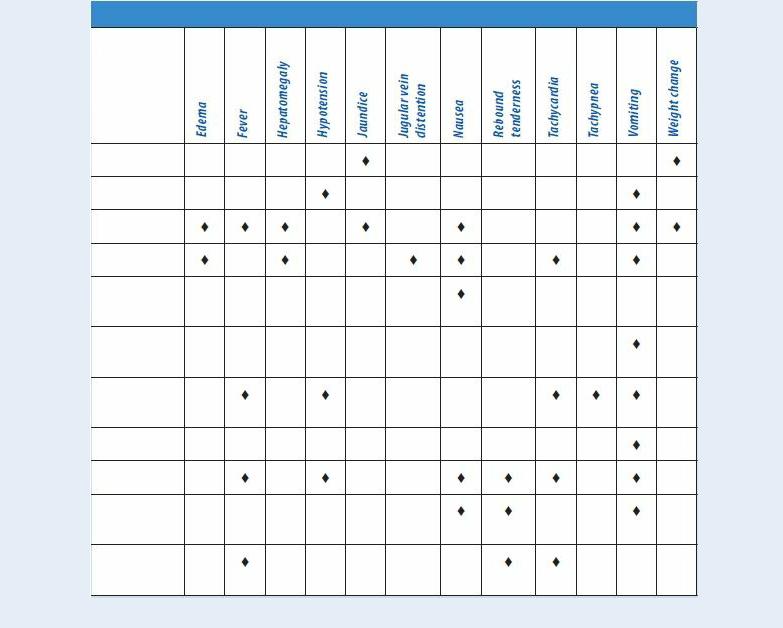

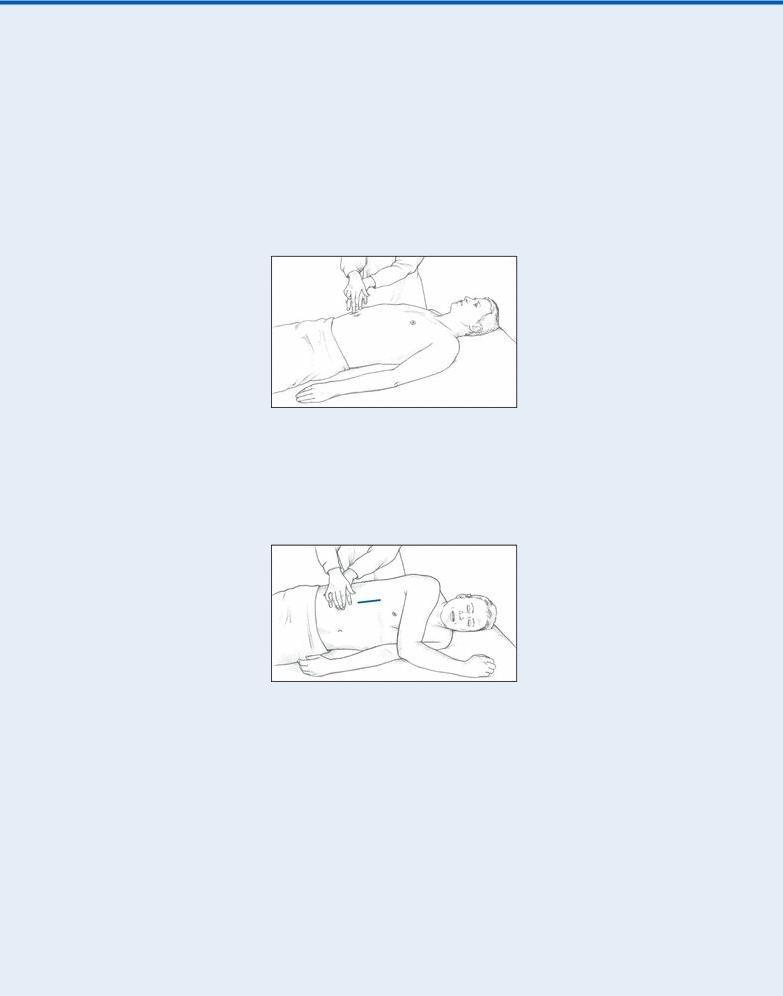

SHIFTING DULLNESS

Step 1. With the patient in a supine position, percuss from the umbilicus outward to the flank, as shown. Draw a line on the patient’s skin to mark the change from tympany to dullness.

Step 2. Turn the patient onto his side. (Note that this positioning causes ascitic fluid to shift.) Percuss again, and mark the change from tympany to dullness. A difference between these lines can indicate ascites.

FLUID WAVE

Have another person press deeply into the patient’s midline to prevent vibration from traveling along the abdominal wall. Place one of your palms on one of the patient’s flanks. Strike the opposite flank with your other hand. If you feel the blow in the opposite palm, ascitic fluid is present.

PUDDLE SIGN

Position the patient on his elbows and knees, which causes ascitic fluid to pool in the most dependent part of the abdomen. Percuss the abdomen from the flank to the midline. The percussion note becomes louder at the edge of the puddle, or the ascitic pool.

Next, percuss and palpate the abdomen to determine if distention results from air, fluid, or both. A tympanic note in the left lower quadrant suggests an air-filled descending or sigmoid colon. A tympanic note throughout a generally distended abdomen suggests an air-filled peritoneal cavity. A dull percussion note throughout a generally distended abdomen suggests a fluid-filled peritoneal cavity. Shifting of dullness laterally with the patient in the decubitus position also indicates a fluidfilled abdominal cavity. A pelvic or intra-abdominal mass causes local dullness upon percussion and should be palpable. Obesity causes a large abdomen without shifting dullness, prominent tympany, or palpable bowel or other masses, with generalized rather than localized dullness.

Palpate the abdomen for tenderness, noting whether it’s localized or generalized. Watch for peritoneal signs and symptoms, such as rebound tenderness, guarding, rigidity, McBurney’s point, obturator sign, and psoas sign. Female patients should undergo a pelvic examination and males, a genital examination. All patients who report abdominal pain should undergo a digital rectal examination with fecal occult blood testing. Finally, measure the patient’s abdominal girth for a baseline value. Mark the flanks with a felt-tipped pen as a reference for subsequent measurements.

Medical Causes

Abdominal cancer. Generalized abdominal distention may occur when the cancer — most commonly ovarian, hepatic, or pancreatic — produces ascites (usually in a patient with a known tumor). It’s an indication of advanced disease. Shifting dullness and a fluid wave accompany distention. Associated signs and symptoms may include severe abdominal pain, an abdominal

mass, anorexia, jaundice, GI hemorrhage (hematemesis or melena), dyspepsia, and weight loss that progresses to muscle weakness and atrophy.

Abdominal trauma. When brisk internal bleeding accompanies trauma, abdominal distention may be acute and dramatic. Associated signs and symptoms of this life-threatening disorder include abdominal rigidity with guarding, decreased or absent bowel sounds, vomiting, tenderness, and abdominal bruising. Pain may occur over the trauma site or over the scapula if abdominal bleeding irritates the phrenic nerve. Signs of hypovolemic shock (such as hypotension and rapid, thready pulse) appear with significant blood loss.

Cirrhosis. In cirrhosis, ascites causes generalized distention and is confirmed by a fluid wave, shifting dullness, and a puddle sign. Umbilical eversion and caput medusae (dilated veins around the umbilicus) are common. The patient may report a feeling of fullness or weight gain. Associated findings include vague abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, bleeding tendencies, severe pruritus, palmar erythema, spider angiomas, leg edema, and possibly splenomegaly. Hematemesis, encephalopathy, gynecomastia, or testicular atrophy may also be seen. Jaundice is usually a late sign. Hepatomegaly occurs initially, but the liver may not be palpable if the patient has advanced disease.

Heart failure. Generalized abdominal distention due to ascites typically accompanies severe cardiovascular impairment and is confirmed by shifting dullness and a fluid wave. Signs and symptoms of heart failure are numerous and depend on the disease stage and degree of cardiovascular impairment. Hallmarks include peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, dyspnea, and tachycardia. Common associated signs and symptoms include hepatomegaly (which may cause right upper quadrant pain), nausea, vomiting, a productive cough, crackles, cool extremities, cyanotic nail beds, nocturia, exercise intolerance, nocturnal wheezing, diastolic hypertension, and cardiomegaly.

Irritable bowel syndrome. Irritable bowel syndrome may produce intermittent, localized distention — the result of periodic intestinal spasms. Lower abdominal pain or cramping typically accompanies these spasms. The pain is usually relieved by defecation or by passage of intestinal gas and is aggravated by stress. Other possible signs and symptoms include diarrhea that may alternate with constipation or normal bowel function, nausea, dyspepsia, straining and urgency at defecation, a feeling of incomplete evacuation, and small, mucus-streaked stools.

Large-bowel obstruction. Dramatic abdominal distention is characteristic in this lifethreatening disorder; in fact, loops of the large bowel may become visible on the abdomen. Constipation precedes distention and may be the only symptom for days. Associated findings include tympany, high-pitched bowel sounds, and the sudden onset of colicky lower abdominal pain that becomes persistent. Fecal vomiting and diminished peristaltic waves and bowel sounds are late signs.

Mesenteric artery occlusion (acute). In this life-threatening disorder, abdominal distention usually occurs several hours after the sudden onset of severe, colicky periumbilical pain accompanied by rapid (even forceful) bowel evacuation. The pain later becomes constant and diffuse. Related signs and symptoms include severe abdominal tenderness with guarding and rigidity, absent bowel sounds and, occasionally, a bruit in the right iliac fossa. The patient may also experience vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, or constipation. Late signs include fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. Abdominal distention or GI bleeding may be the only clue if pain is absent.

Paralytic ileus. Paralytic ileus, which produces generalized distention with a tympanic

percussion note, is accompanied by absent or hypoactive bowel sounds and, occasionally, mild abdominal pain and vomiting. The patient may be severely constipated or may pass flatus and small, liquid stools.

Peritonitis. Peritonitis is a life-threatening disorder in which abdominal distention may be localized or generalized, depending on the extent of the inflammation. Fluid accumulates within the peritoneal cavity and then within the bowel lumen, causing a fluid wave and shifting dullness. Typically, distention is accompanied by sudden and severe abdominal pain that worsens with movement, rebound tenderness, and abdominal rigidity.

The skin over the patient’s abdomen may appear taut. Associated signs and symptoms usually include hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, fever, chills, hyperalgesia, nausea, and vomiting. Signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension, appear with significant fluid loss into the abdomen.

Small-bowel obstruction. Abdominal distention is characteristic in small-bowel obstruction, a life-threatening disorder, and is most pronounced during late obstruction, especially in the distal small bowel. Auscultation reveals hypoactive or hyperactive bowel sounds, whereas percussion produces a tympanic note. Accompanying signs and symptoms include colicky periumbilical pain, constipation, nausea, and vomiting; the higher the obstruction, the earlier and more severe the vomiting. Rebound tenderness reflects intestinal strangulation with ischemia. Associated signs and symptoms include drowsiness, malaise, and signs of dehydration. Signs of hypovolemic shock appear with progressive dehydration and plasma loss.

Toxic megacolon (acute). Toxic megacolon is a life-threatening complication of infectious or ulcerative colitis. It produces dramatic abdominal distention that usually develops gradually and is accompanied by a tympanic percussion note, diminished or absent bowel sounds, and mild rebound tenderness. The patient also presents with abdominal pain and tenderness, fever, tachycardia, and dehydration.

Special Considerations

Position the patient comfortably, using pillows for support. Place him on his left side to help flatus escape. Or, if he has ascites, elevate the head of the bed to ease his breathing. Administer drugs to relieve pain, and offer emotional support.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as abdominal X-rays, endoscopy, laparoscopy, ultrasonography, computed tomography scan or, possibly, paracentesis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient to use slow breathing to help relieve abdominal discomfort, and emphasize the importance of oral hygiene to prevent dry mouth. If the patient has an obstruction or ascites, tell him which foods and fluids to avoid.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a young child’s abdomen is normally rounded, distention may be difficult to observe. Fortunately, a child’s abdominal wall is less well developed than an adult’s, making palpation easier. When percussing the abdomen, remember that a child normally swallows air when eating and crying, resulting in louder-than-normal tympany. Minimal tympany with abdominal distention may result from fluid accumulation or solid masses. To check for abdominal fluid, test for shifting dullness instead of

a fluid wave. (In a child, air swallowing and incomplete abdominal muscle development make the fluid wave difficult to interpret.)

Sometimes, a child won’t cooperate with a physical examination. Try to gain the child’s confidence, and consider allowing him to remain in the parent’s or caregiver’s lap. You can gather clues by observing the child while he’s coughing, walking, or even climbing on office furniture. Remove all the child’s clothing to avoid missing diagnostic clues. Also, perform a gentle rectal examination.

In neonates, ascites usually result from GI or urinary perforation; in older children, from heart failure, cirrhosis, or nephrosis. Besides ascites, congenital malformations of the GI tract (such as intussusception and volvulus) may cause abdominal distention. A hernia may cause distention if it produces an intestinal obstruction. In addition, overeating and constipation can cause distention.

Geriatric Pointers

As people age, fat tends to accumulate in the lower abdomen and near the hips, even when body weight is stable. This accumulation, together with weakening abdominal muscles, commonly produces a potbelly, which some elderly patients interpret as fluid collection or evidence of disease.

REFERENCES

Bebars, G. (2011). Shock, mental status deterioration, and abdominal distention in an elderly man. Medscape, January 14, 2011. Sanders, M., & Gunn-Sanders, A. (2011). Insidious abdominal symptoms with urinary disturbances. Medscape, September 2011.

Abdominal Mass

(See Also Abdominal Distention, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal

Rigidity)

Commonly detected on routine physical examination, an abdominal mass is a localized swelling in one abdominal quadrant. Typically, this sign develops insidiously and may represent an enlarged organ, a neoplasm, an abscess, a vascular defect, or a fecal mass.

Distinguishing an abdominal mass from a normal structure requires skillful palpation. At times, palpation must be repeated with the patient in a different position or performed by a second examiner to verify initial findings. A palpable abdominal mass is an important clinical sign and usually represents a serious — and perhaps life-threatening — disorder.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has a pulsating midabdominal mass and severe abdominal or back pain, suspect an aortic aneurysm. Quickly take his vital signs. Because the patient may require emergency surgery, withhold food or fluids until he’s examined. Prepare to administer oxygen and to start an I.V. infusion for fluid and blood replacement. Obtain routine preoperative tests, and prepare the patient for angiography. Frequently monitor blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and urine output.

Be alert for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, and cool clammy skin, which may indicate significant blood loss.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s abdominal mass doesn’t suggest an aortic aneurysm, continue with a detailed history. Ask the patient if the mass is painful. If so, ask if the pain is constant or if it occurs only on palpation. Is it localized or generalized? Determine if the patient was already aware of the mass. If he was, find out if he noticed any change in the size or location of the mass.

Next, review the patient’s medical history, paying special attention to GI disorders. Ask the patient about GI symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, abnormally colored stools, and vomiting. Has the patient noticed a change in his appetite? If the patient is female, ask whether her menstrual cycles are regular and when the first day of her last menstrual period was.

A complete physical examination should be performed. Next, auscultate for bowel sounds in each quadrant. Listen for bruits or friction rubs, and check for enlarged veins. Lightly palpate and then deeply palpate the abdomen, assessing any painful or suspicious areas last. Note the patient’s position when you locate the mass. Some masses can be detected only with the patient in a supine position; others require a sidelying position.

Estimate the size of the mass in centimeters. Determine its shape. Is it round or sausage shaped? Describe its contour as smooth, rough, sharply defined, nodular, or irregular. Determine the consistency of the mass. Is it doughy, soft, solid, or hard? Also, percuss the mass. A dull sound indicates a fluid-filled mass and a tympanic sound, an air-filled mass.

Next, determine if the mass moves with your hand or in response to respiration. Is the mass freefloating or attached to intra-abdominal structures? To determine whether the mass is located in the abdominal wall or the abdominal cavity, ask the patient to lift his head and shoulders off the examination table, thereby contracting his abdominal muscles. While these muscles are contracted, try to palpate the mass. If you can, the mass is in the abdominal wall; if you can’t, the mass is within the abdominal cavity. (See Abdominal Masses: Locations and Common Causes, page 10.)

After the abdominal examination is complete, perform pelvic, genital, and rectal examinations.

Medical Causes

Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Abdominal aortic aneurysm may persist for years, producing only a pulsating periumbilical mass with a systolic bruit over the aorta. However, it may become life threatening if the aneurysm expands and its walls weaken. In such cases, the patient initially reports constant upper abdominal pain or, less commonly, low back or dull abdominal pain. If the aneurysm ruptures, he’ll report severe abdominal and back pain. After rupture, the aneurysm no longer pulsates.

Associated signs and symptoms of rupture include mottled skin below the waist, absent femoral and pedal pulses, lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, mild to moderate tenderness with guarding, and abdominal rigidity. Signs of shock — such as tachycardia and cool, clammy skin — appear with significant blood loss.

Abdominal Masses: Locations and Common Causes