Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfA woman who’s familiar with the feel of her breasts and performs monthly breast selfexamination can detect a nodule 6.4 mm or less in size, considerably smaller than the 1-cm nodule that’s readily detectable by an experienced examiner. However, a woman may fail to report a nodule because of the fear of breast cancer.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports a lump, ask her how and when she discovered it. Does the size and tenderness of the lump vary with her menstrual cycle? Has the lump changed since she first noticed it? Has she noticed other breast signs, such as a change in breast shape, size, or contour, a discharge, or nipple changes?

Is she breast-feeding? Does she have fever, chills, fatigue, or other flulike signs or symptoms? Ask her to describe any pain or tenderness associated with the lump. Is the pain in one breast only? Has she sustained recent trauma to the breast?

Explore the patient’s medical and family history for factors that increase her risk of breast cancer. These include a high-fat diet, having a mother or sister with breast cancer, or having a history of cancer, especially cancer in the other breast. Other risk factors include nulliparity and a first pregnancy after age 30.

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

In the United States, breast cancer incidence is higher among white women than any other racial or ethnic group. Yet, breast cancer mortality is highest among black women.

Next, perform a thorough breast examination. Pay special attention to the upper outer quadrant of each breast, where one-half of the ductal tissue is located. This is the most common site of malignant breast tumors.

Carefully palpate a suspected breast nodule, noting its location, shape, size, consistency, mobility, and delineation. Does the nodule feel soft, rubbery, and elastic or hard? Is it mobile, slipping away from your fingers as you palpate it, or firmly fixed to adjacent tissue? Does the nodule seem to limit the mobility of the entire breast? Note the nodule’s delineation. Are the borders clearly defined or indefinite? Does the area feel more like a hardness or diffuse induration than a nodule with definite borders?

Do you feel one nodule or several small ones? Is the shape round, oval, lobular, or irregular? Inspect and palpate the skin over the nodule for warmth, redness, and edema. Palpate the lymph nodes of the breast and axilla for enlargement.

Observe the contour of the breasts, looking for asymmetry and irregularities. Be alert for signs of retraction, such as skin dimpling and nipple deviation, retraction, or flattening. (To exaggerate dimpling, have your patient raise her arms over her head or press her hands against her hips.) Gently pull the breast skin toward the clavicle. Is dimpling evident? Mold the breast skin and again observe the area for dimpling.

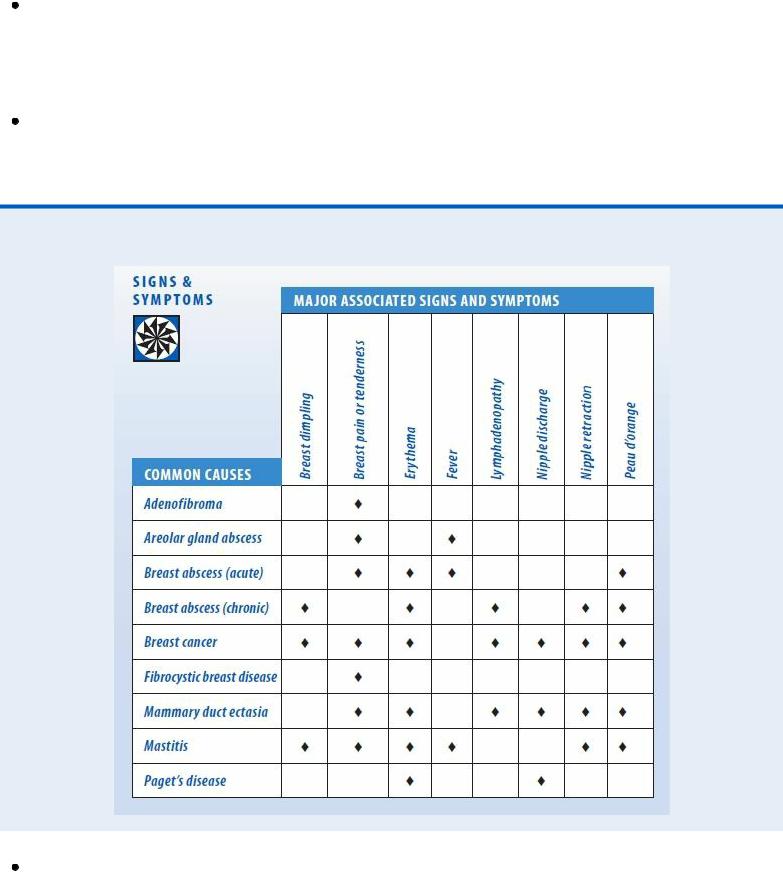

Be alert for a nipple discharge that’s spontaneous, unilateral, and nonmilky (serous, bloody, or purulent). Be careful not to confuse it with the grayish discharge that can be elicited from the nipples of a woman who has been pregnant. (See Breast Nodule: Common Causes and Associated Findings, page 122.)

Medical Causes

Adenofibroma. The extremely mobile or “slippery” feel of this benign neoplasm helps distinguish it from other breast nodules. The nodule usually occurs singly and characteristically feels firm, elastic, and round or lobular, with well-defined margins. It doesn’t cause pain or tenderness, can vary from pinhead size to very large, commonly grows rapidly, and usually lies around the nipple or on the lateral side of the upper outer quadrant.

Areolar gland abscess. Areolar gland abscess is a tender, palpable mass on the periphery of the areola following an inflammation of the sebaceous glands of Montgomery. Fever may also be present.

Breast Nodule: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Breast abscess. A localized, hot, tender, fluctuant mass with erythema and peau d’orange typifies an acute abscess. Associated signs and symptoms include fever, chills, malaise, and generalized discomfort. With a chronic abscess, the nodule is nontender, irregular, and firm and may feel like a thick wall of fibrous tissue. It’s commonly accompanied by skin dimpling, peau d’orange, nipple retraction and, sometimes, axillary lymphadenopathy.

Breast cancer. A hard, poorly delineated nodule that’s fixed to the skin or underlying tissue suggests breast cancer. Malignant nodules typically cause breast dimpling, nipple deviation or retraction, or flattening of the nipple or breast contour. Between 40% and 50% of malignant nodules occur in the upper outer quadrant.

Nodules usually occur singly, although satellite nodules may surround the main one. They’re usually nontender. Nipple discharge may be serous or bloody. (A bloody nipple discharge in the presence of a nodule is a classic sign of breast cancer.) Additional findings include edema (peau d’orange) of the skin overlying the mass, erythema, tenderness, and axillary lymphadenopathy. A breast ulcer may occur as a late sign. Breast pain, an unreliable symptom, may be present.

Fibrocystic breast disease. The most common cause of breast nodules, this fibrocystic condition produces smooth, round, slightly elastic nodules, which increase in size and tenderness just before menstruation. The nodules may occur in fine, granular clusters in both breasts or as widespread, well-defined lumps of varying sizes. A thickening of adjacent tissue may be palpable. Cystic nodules are mobile, which helps differentiate them from malignant ones. Because cystic nodules aren’t fixed to underlying breast tissue, they don’t produce retraction signs, such as nipple deviation or dimpling. Signs and symptoms of premenstrual syndrome — including headache, irritability, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping — may also be present.

Mammary duct ectasia. The rubbery breast nodule in mammary duct ectasia, a menopausal or postmenopausal disorder, usually lies under the areola. It’s commonly accompanied by transient pain, itching, tenderness, and erythema of the areola; thick, sticky, multicolored nipple discharge from multiple ducts; and nipple retraction. The skin overlying the mass may be bluish green or exhibit peau d’orange. Axillary lymphadenopathy is possible.

Mastitis. With mastitis, breast nodules feel firm and indurated or tender, flocculent, and discrete. Gentle palpation defines the area of maximum purulent accumulation. Skin dimpling and nipple deviation, retraction, or flattening may be present, and the nipple may show a crack or abrasion. Accompanying signs and symptoms include breast warmth, erythema, tenderness, and peau d’orange, as well as a high fever, chills, malaise, and fatigue.

Paget’s disease. Paget’s disease is a slow-growing intraductal carcinoma that begins as a scaling, eczematoid unilateral nipple lesion. The nipple later becomes reddened and excoriated and may eventually be completely destroyed. The process extends along the skin as well as in the ducts, usually progressing to a deep-seated mass.

Special Considerations

Although many women regard a breast lump as a sign of breast cancer, most nodules are benign. As a result, try to avoid alarming the patient further. Provide a simple explanation of your examination, and encourage her to express her feelings.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, which may include transillumination, mammography, thermography, needle aspiration or open biopsy of the nodule for tissue examination, and cytologic examination of nipple discharge.

Postpone teaching the patient how to perform breast self-examination until she overcomes her initial anxiety at discovering a nodule. Regular breast self-examination is especially important for women who have had a previous cancer, have a family history of breast cancer, are nulliparous, or had their first child after age 30.

Although most nodules occurring in the breast-feeding patient result from mastitis, the possibility of cancer demands careful evaluation. Advise the patient with mastitis to pump her breasts to prevent further milk stasis, to discard the milk, and to substitute formula until the infection responds to antibiotics.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient the techniques of breast self-examination. Explain how to treat mastitis.

Pediatric Pointers

Most nodules in children and adolescents reflect the normal response of breast tissue to hormonal fluctuations. For instance, the breasts of young teenage girls may normally contain cordlike nodules that become tender just before menstruation.

A transient breast nodule in young boys (as well as in women between ages 20 and 30) may result from juvenile mastitis, which usually affects one breast. Signs of inflammation are present in a firm mass beneath the nipple.

Geriatric Pointers

In women age 70 and older, three-quarters of all breast lumps are malignant.

REFERENCES

Benner, C. , Carabin, H. , Sánchez-Serrano, L. P. , Budke, C. M., & Carmena D. (2010) . Analysis of the economic impact of cystic echinococcosis in Spain. Bulletin of World Health Organization, 88(1), 49–57.

Masroor, I. , Azeemuddin, M. , Khan, S., & Barakzai, A. (2010) . Hydatid disease of the breast. Singapore Medical Journal, 51(4), 72–75.

Breast Pain

(See Also Breast Dimpling, Breast Nodule, Breast Ulcer) [Mastalgia]

An unreliable indicator of cancer, breast pain commonly results from benign breast disease. It may occur during rest or movement and may be aggravated by manipulation or palpation. (Breast tenderness refers to pain elicited by physical contact.) Breast pain may be unilateral or bilateral; cyclic, intermittent, or constant; and dull or sharp. It may result from surface cuts, furuncles, contusions, or similar lesions (superficial pain); nipple fissures or inflammation in the papillary ducts or areolae (severe localized pain); stromal distention in the breast parenchyma; a tumor that affects nerve endings (severe, constant pain); or inflammatory lesions that distend the stroma and irritate sensory nerve endings (severe, constant pain). Breast pain may radiate to the back, the arms, and, sometimes, the neck.

Breast tenderness in women may occur before menstruation and during pregnancy. Before menstruation, breast pain or tenderness stems from increased mammary blood flow due to hormonal changes. During pregnancy, breast tenderness and throbbing, tingling, or pricking sensations may

occur, also from hormonal changes. In men, breast pain may stem from gynecomastia (especially during puberty and senescence), reproductive tract anomalies, or organic disease of the liver or pituitary, adrenal cortex, or thyroid glands.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient if breast pain is constant or intermittent. For either type, ask about onset and character. If it’s intermittent, determine the relationship of pain to the phase of the menstrual cycle. Is the patient a nursing mother? If not, ask about any nipple discharge and have her describe it. Is she pregnant? Has she reached menopause? Has she recently experienced flulike symptoms or sustained injury to the breast? Has she noticed a change in breast shape or contour?

Ask the patient to describe the pain. She may describe it as sticking, stinging, shooting, stabbing, throbbing, or burning. Determine if the pain affects one breast or both, and ask the patient to point to the painful area.

Instruct the patient to place her arms at her sides, and inspect the breasts. Note their size, symmetry, and contour and the appearance of the skin. Remember that breast shape and size vary and that breasts normally change during menses, pregnancy, and lactation and with aging. Are the breasts red or edematous? Are the veins prominent?

Note the size, shape, and symmetry of the nipples and areolae. Do you detect ecchymosis, a rash, ulceration, or a discharge? Do the nipples point in the same direction? Do you see signs of retraction, such as skin dimpling or nipple inversion or flattening? Repeat your inspection, first with the patient’s arms raised above her head and then with her hands pressed against her hips.

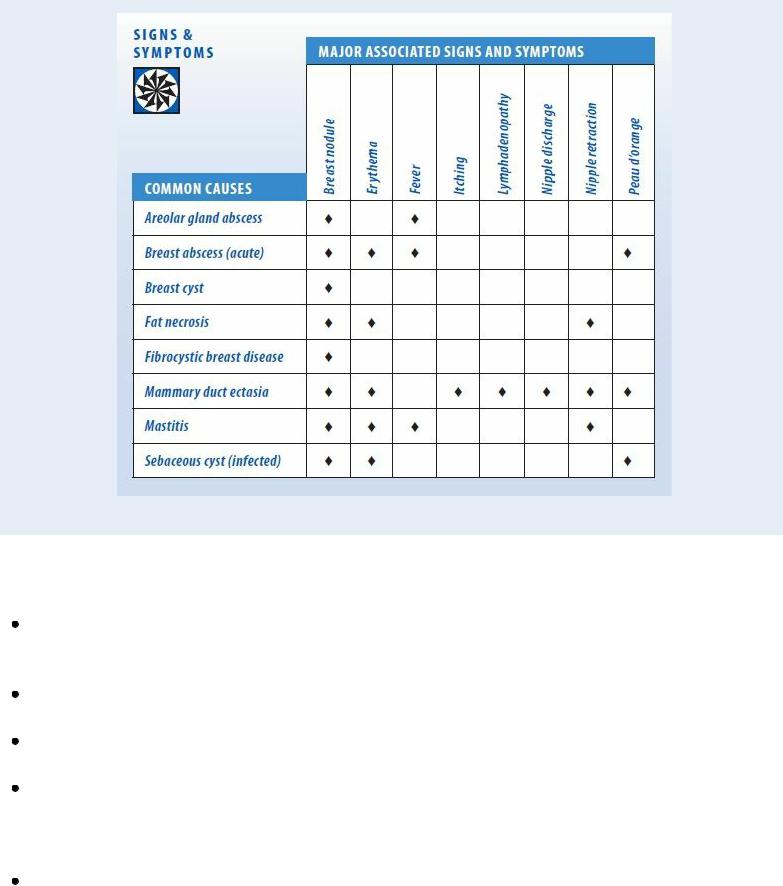

Palpate the breasts, first with the patient seated and then with her lying down and a pillow placed under her shoulder on the side being examined. Use the pads of your fingers to compress breast tissue against the chest wall. Proceed systematically from the sternum to the midline and from the axilla to the midline, noting any warmth, tenderness, nodules, masses, or irregularities. Palpate the nipple, noting tenderness and nodules, and check for discharge. Palpate axillary lymph nodes, noting any enlargement. (See Breast Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

Breast Pain: Common Causes and Associated FindingsSIGNS

& SYMPTOMS

Medical Causes

Areolar gland abscess. Areolar gland abscess is a tender, palpable mass on the periphery of the areola following an inflammation of the sebaceous glands of Montgomery. Fever may also occur.

Breast abscess (acute). In the affected breast, local pain, tenderness, erythema, peau d’orange, and warmth are associated with a nodule. Malaise, fever, and chills may also occur.

Breast cyst. A breast cyst that enlarges rapidly may cause acute, localized, and usually unilateral pain. A palpable breast nodule may be present.

Fat necrosis. Local pain and tenderness may develop in fat necrosis, a benign disorder. A history of trauma usually is present. Associated findings include ecchymosis; erythema of the overriding skin; a firm, irregular, fixed mass; and skin retraction signs, such as skin dimpling and nipple retraction. Fat necrosis may be hard to differentiate from cancer.

Fibrocystic breast disease. Fibrocystic breast disease is a common cause of breast pain that’s associated with the development of cysts that may cause pain before menstruation and are asymptomatic afterward. Later in the course of the disorder, pain and tenderness may persist throughout the cycle. The cysts feel firm, mobile, and well defined. Many are bilateral and found in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, but others are unilateral and generalized. Signs and symptoms of premenstrual syndrome — including headache, irritability, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping — may also be present.

Mammary duct ectasia. Burning pain and itching around the areola may occur, although ectasia is commonly asymptomatic at first. The history may include one or more episodes of inflammation with pain, tenderness, erythema, and acute fever, or with pain and tenderness alone, which develop and then subside spontaneously within 7 to 10 days. Other findings include a rubbery, subareolar breast nodule; swelling and erythema around the nipple; nipple retraction; a bluish green discoloration or peau d’orange of the skin overlying the nodule; a thick, sticky, multicolored nipple discharge from multiple ducts; and axillary lymphadenopathy. A breast ulcer may occur in late stages.

Mastitis. Unilateral pain may be severe, particularly when the inflammation occurs near the skin surface. Breast skin is typically red and warm at the inflammation site; peau d’orange may be present. Palpation reveals a firm area of induration. Skin retraction signs — such as breast dimpling and nipple deviation, inversion, or flattening — may be present. Systemic signs and symptoms — such as high fever, chills, malaise, and fatigue — may also occur.

Sebaceous cyst (infected). Breast pain may be reported with sebaceous cyst, a cutaneous cyst. Associated symptoms include a small, well-delineated nodule, localized erythema, and induration.

Special Considerations

Provide emotional support for the patient, and emphasize the importance of monthly breast selfexamination.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as mammography, ultrasonography, thermography, cytology of nipple discharge, biopsy, or culture of any aspirate.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient on the correct type of brassiere, teach the techniques of breast self-examination, and stress the importance of monthly self-examination. Explain the use of warm or cold compresses.

Pediatric Pointers

Transient gynecomastia can cause breast pain in males during puberty.

Geriatric Pointers

Breast pain secondary to benign breast disease is rare in postmenopausal women. Breast pain can also be due to trauma from falls or physical abuse. Because of decreased pain perception and decreased cognitive function, elderly patients may not report breast pain.

REFERENCES

Gärtner, R. , Jensen, M. B., Nielsen, J. , Ewertz, M. , Kroman, N., & Kehlet, H. (2009) . Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302, 1985.

Loftus, L. S., & Laronga, C. (2009). Evaluating patients with chronic pain after breast cancer surgery: The search for relief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302, 2034.

Breast Ulcer

(See Also Breast Dimpling, Breast Nodule, Breast Pain)

Appearing on the nipple, areola, or the breast itself, an ulcer indicates destruction of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. A breast ulcer is usually a late sign of cancer, appearing well after the confirming diagnosis. Breast ulcers can also result from trauma, infection, or radiation.

History and Physical Examination

Begin the history by asking when the patient first noticed the ulcer and if it was preceded by other breast changes, such as nodules, edema, or nipple discharge, deviation, or retraction. Does the ulcer seem to be getting better or worse? Does it cause pain or produce drainage? Has she noticed any change in breast shape? Has she had a skin rash? If she has been treating the ulcer at home, find out how.

Review the patient’s personal and family history for factors that increase the risk of breast cancer. Ask, for example, about previous cancer, especially of the breast, and mastectomy. Determine whether the patient’s mother or sister has had breast cancer. Ask the patient’s age at menarche and menopause because more than 30 years of menstrual activity increases the risk of breast cancer. Also, ask about pregnancy because nulliparity or birth of a first child after age 30 also increases the risk of breast cancer.

If the patient recently gave birth, ask if she breast-feeds her infant or has recently weaned him. Ask if she’s currently taking an oral antibiotic and if she’s diabetic. All these factors predispose the patient to Candida infections.

Inspect the patient’s breast, noting any asymmetry or flattening. Look for a rash, scaling, cracking, or red excoriation on the nipples, areola, and inframammary fold. Check especially for skin changes, such as warmth, erythema, or peau d’orange. Palpate the breast for masses, noting any induration beneath the ulcer. Then, carefully palpate for tenderness or nodules around the areola and the axillary lymph nodes.

Medical Causes

Breast cancer. A breast ulcer that doesn’t heal within a month usually indicates cancer. Ulceration along a mastectomy scar may indicate metastatic cancer; a nodule beneath the ulcer may be a late sign of a fulminating tumor. Other signs include a palpable breast nodule, skin dimpling, nipple retraction, bloody or serous nipple discharge, erythema, peau d’orange, and enlarged axillary lymph nodes.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

A breast ulcer may be the presenting sign of breast cancer in men, who are more apt to miss or dismiss earlier breast changes.

Breast trauma. Tissue destruction with inadequate healing may produce breast ulcers. Associated signs depend on the type of trauma but may include ecchymosis, lacerations, abrasions, swelling, and hematoma.

Candida albicans infection. Severe Candida infection can cause maceration of breast tissue

followed by ulceration. Well-defined, bright-red papular patches — usually with scaly borders

— characterize the infection, which can develop in the breast folds. In breast-feeding women, cracked nipples predispose them to infection. Women describe the pain, felt when the infant sucks, as a burning pain that penetrates into the chest wall.

Paget’s disease. Bright-red nipple excoriation can extend to the areola and ulcerate. Serous or bloody nipple discharge and extreme nipple itching may accompany ulceration. Symptoms are usually unilateral.

Other Causes

Radiation therapy. After treatment, the breasts appear “sunburned.” Subsequently, the skin ulcerates and the surrounding area becomes red and tender.

Special Considerations

If breast cancer is suspected, provide emotional support and encourage the patient to express her feelings. Prepare her for diagnostic tests, such as ultrasonography, thermography, mammography, nipple discharge cytology, and breast biopsy. If a Candida infection is suspected, prepare her for skin or blood cultures.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to apply a topical antifungal or antibacterial ointment or cream. Instruct her to keep the ulcer dry to reduce chafing and to wear loose-fitting undergarments. Explain the importance of clinical breast examination and mammography following the American Cancer Society guidelines. Teach the patient about the cause of the breast ulcer and about the treatment plan after the diagnosis is established.

Geriatric Pointers

Because of the increased breast cancer risk in this population, breast ulcers should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise. However, ulcers can also result from normal skin changes in the elderly, such as thinning, decreased vascularity, and loss of elasticity, as well as from poor skin hygiene. Pressure ulcers may result from restraints and tight brassieres; traumatic ulcers may result from falls or abuse.

REFERENCES

Levine, S. M., Lester, M. E., Fontenot, B., & Allen, R. J. (2011) . Perforator flap breast reconstruction after unsatisfactory implant reconstruction. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 66(5), 513–517.

Visser, N. J. , Damen, T. H., Timman, R. , Hofer, S. O., & Mureau, M. A. (2010) . Surgical results, aesthetic outcome, and patient satisfaction after microsurgical autologous breast reconstruction following failed implant reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 126(1), 26–36.

Breath with Ammonia Odor [Uremic fetor]

The odor of ammonia on the breath — described as urinous or “fishy” breath — typically occurs in

end-stage chronic renal failure. This sign improves slightly after hemodialysis and persists throughout the course of the disorder, but isn’t of great concern.

Ammonia breath odor reflects the long-term metabolic disturbances and biochemical abnormalities associated with uremia and end-stage chronic renal failure. It’s produced by metabolic end products blown off by the lungs and the breakdown of urea (to ammonia) in the saliva. However, a specific uremic toxin hasn’t been identified. In animals, breath odor analysis has revealed toxic metabolites, such as dimethylamine and trimethylamine, which contribute to the “fishy” odor. The source of these amines, although still unclear, may be intestinal bacteria acting on dietary chlorine.

History and Physical Examination

When you detect ammonia breath odor, the diagnosis of chronic renal failure will probably be well established. Look for associated GI symptoms so that palliative care and support can be individualized.

Inspect the patient’s oral cavity for bleeding, swollen gums or tongue, and ulceration with drainage. Ask the patient if he has experienced a metallic taste, loss of smell, increased thirst, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, loss of appetite at the sight of food, or early morning vomiting. Because GI bleeding is common in patients with chronic renal failure, ask about bowel habits, noting especially melanous stools or constipation.

Take the patient’s vital signs. Watch for indications of hypertension (the patient with end-stage chronic renal failure is usually somewhat hypertensive) or hypotension. Be alert for other signs of shock (such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin) and altered mental status. Significant changes can indicate complications, such as massive GI bleeding or pericarditis with tamponade.

Medical Causes

End-stage chronic renal failure. Ammonia breath odor is a late finding. Accompanying signs and symptoms include anuria, skin pigmentation changes and excoriation, brown arcs under the nail margins, tissue wasting, Kussmaul’s respirations, neuropathy, lethargy, somnolence, confusion, disorientation, behavior changes with irritability, and mood lability. Later neurologic signs that signal impending uremic coma include muscle twitching and fasciculation, asterixis, paresthesia, and footdrop. Cardiovascular findings include hypertension, myocardial infarction, signs of heart failure, pericarditis, and even sudden death and stroke. GI findings include anorexia, nausea, heartburn, vomiting, constipation, hiccups, and a metallic taste, with oral signs and symptoms, such as stomatitis, gum ulceration and bleeding, and a coated tongue. The patient has an increased risk of peptic ulceration and acute pancreatitis. Weight loss is common; uremic frost, pruritus, and signs of hormonal changes, such as impotence or amenorrhea, also appear.

Special Considerations

Ammonia breath odor is offensive to others, but the patient may become accustomed to it. As a result, remind him to perform frequent mouth care. If he’s unable to perform mouth care, do it for him and teach his family members how to assist him.

Maximize dietary intake by offering the patient frequent small meals of his favorite foods, within dietary limitations.