Biomedical EPR Part-B Methodology Instrumentation and Dynamics - Sandra R. Eaton

.pdf150 |

FABIAN GERSON AND GEORG GESCHEIDT |

electrolytically generated inside the cavity, cannot be studied by the ENDOR technique, as the electrodes interfere with the RF coils.

The number of the nuclei giving rise to an ENDOR signal must be verified by close examination, preferably by simulation, of the corresponding EPR spectrum. Other procedures can likewise be used to this aim, e.g. isotopic substitution, which also serves for the assignment of coupling constants to sets of equivalent nuclei. ENDOR spectroscopy is particularly suited for such an assignment, because the signals of different isotopes appear in separate frequency regions. Relative numbers of nuclei responsible for the signals can be determined by techniques such as specialTRIPLE resonance, while the relative signs of the coupling constants  are obtainable by general-TRIPLE resonance.

are obtainable by general-TRIPLE resonance.

1.4Triple Resonance

This technique requires a second powerful RF source. In the special- TRIPLE-resonance or double-ENDOR experiment (Kurreck et al., 1984; Kurreck, et al., 1988), the sample is irradiated simultaneously with two RF fields, in addition to the saturating MW irradiation, so that both NMR transitions  and

and  (Figure 1) are excited at the same time. According to schemes (c) and (d) of this Figure, such procedure should double the ENDOR enhancement, because it leads simultaneously to

(Figure 1) are excited at the same time. According to schemes (c) and (d) of this Figure, such procedure should double the ENDOR enhancement, because it leads simultaneously to  in

in  and

and  in

in  thus yielding for the levels involved in the relevant EPR

thus yielding for the levels involved in the relevant EPR

transition  a difference

a difference  instead of

instead of  achieved with a single RF source. The main advantage of special-TRIPLE resonance is that the signal intensities reproduce better the relative number of nuclei giving rise to them than it does ENDOR spectroscopy. The special-TRIPLE-resonance signal, associated with the coupling constant

achieved with a single RF source. The main advantage of special-TRIPLE resonance is that the signal intensities reproduce better the relative number of nuclei giving rise to them than it does ENDOR spectroscopy. The special-TRIPLE-resonance signal, associated with the coupling constant  appears separated from the origin (NMR frequency

appears separated from the origin (NMR frequency  by

by  in unit of

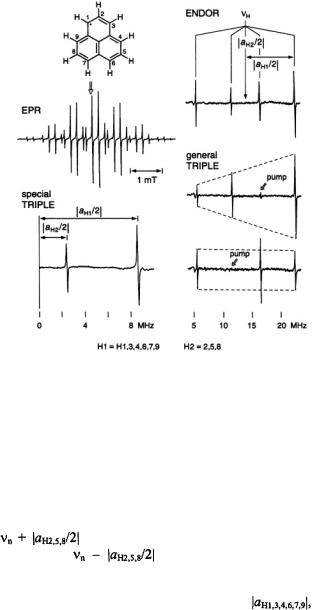

in unit of  As shown in Figure 3 for the phenalenyl radical (Kurreck et al., 1984), the intensities of the special- TRIPLE-resonance signals from the six protons in the 1,3,4,6,7,9-positions relative to those from the three protons in the 2,5,8-positions exhibit more exactly the expected ratio 2.

As shown in Figure 3 for the phenalenyl radical (Kurreck et al., 1984), the intensities of the special- TRIPLE-resonance signals from the six protons in the 1,3,4,6,7,9-positions relative to those from the three protons in the 2,5,8-positions exhibit more exactly the expected ratio 2.

Whereas in the special-TRIPLE-resonance experiment the NMR transitions of the same set of protons are irradiated (homonuclear-TRIPLE resonance), in its general-TRIPLE counterpart, transitions of different sets of nuclei are saturated simultaneously (heteronuclear-TRIPLE resonance). One NMR transition is “pumped” with the first (unmodulated) RF frequency, while the second (modulated) RF field is scanned over the whole range of NMR resonances. The “pumping” causes characteristic intensity changes of the highand low-frequency signals relative to those observed by ENDOR. When the high- (low-) frequency signal is pumped, its intensity strongly reduced, while that of the low- (high-) frequency partner, associated with the

SOLUTION ENDOR OF RADICAL IONS |

151 |

same coupling constant, is enhanced, because, for the latter signal, the pumping corresponds to a special-TRIPLE-resonance experiment.

Figure 3. EPR (left, center),  (right, top), and the corresponding special-TRIPLE- resonance (left, bottom) and general-TRIPLE-resonance (right, center and bottom) spectra of the phenalenyl radical; solvent mineral oil, temperature 300 K. The arrow above the EPR spectrum indicates the line selected for saturation, while those in the general-TRIPLE- resonance spectra mark the ENDOR signal chosen for pumping.

(right, top), and the corresponding special-TRIPLE- resonance (left, bottom) and general-TRIPLE-resonance (right, center and bottom) spectra of the phenalenyl radical; solvent mineral oil, temperature 300 K. The arrow above the EPR spectrum indicates the line selected for saturation, while those in the general-TRIPLE- resonance spectra mark the ENDOR signal chosen for pumping.  is the frequency

is the frequency of the free proton. Taken with a Bruker-ER-200-D spectrometer and a Bruker ENB-ENDOR cavity. Reproduced from (Kurreck, et al., 1988) by permission of VCH Publishers.

of the free proton. Taken with a Bruker-ER-200-D spectrometer and a Bruker ENB-ENDOR cavity. Reproduced from (Kurreck, et al., 1988) by permission of VCH Publishers.

Figure 3 demonstrates the effect of pumping the signals separated by the smaller coupling constant,  of the three protons in the 2,5,8-positions

of the three protons in the 2,5,8-positions

of phenalenyl radical |

(Kurreck, et al., 1984). When the high-frequency |

signal at |

is pumped, it nearly disappears, while its low- |

frequency partner at |

is substantially strengthened. An |

opposite effect on the intensities is observed on pumping this low-frequency signal. Simultaneously, striking intensity changes are observed for the pair

of signals separated by the larger coupling constant, |

of the |

six |

protons in the 1,3,4,6,7,9-positions, although neither of these |

signals |

is |

subjected to pumping. As is evident from Figure 3, such changes follow patterns which are diametrically opposed to those induced on the signals

152 |

FABIAN GERSON AND GEORG GESCHEIDT |

|

separated by |

The intensity ratio of the high-frequency signal at |

|

|

to its low-frequency partner at |

increases |

relative to that in the ENDOR spectrum when the high-frequency signal at

|

is pumped. In contrast, this ratio decreases when the pumping is |

|

carried out |

on the low-frequency signal at |

This behavior |

points to opposite signs of the two coupling constants, i.e. |

||

and |

corresponding to –0.629 and +0.181 mT, |

|

respectively (Gerson, 1966). |

|

|

2.QUINONES

2.1Introduction

Quinones are the most common electron acceptors and electron-transfer mediators in biological processes, in which their radical anions (semiquinone anions) play an important role (Morton, 1965). An early ENDOR study of biologically interesting semiquinone anions in fluid solution was published (Das et al., 1970) a few years after ENDOR spectra of organic radicals in solution had been reported for the first time (Hyde and Maki, 1964). The

SOLUTION ENDOR OF RADICAL IONS |

153 |

pertinent semiquinones were the radical anions of  (vitamin E quinone; 1) and ubiquinone (2), which are both derivatives of p- benzoquinone, as well as those of 2-methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (vitamin

(vitamin E quinone; 1) and ubiquinone (2), which are both derivatives of p- benzoquinone, as well as those of 2-methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (vitamin  quinone; 3) and menadione (vitamin

quinone; 3) and menadione (vitamin  quinone; 4) which is another derivative of 1,4-naphthoquinone. Recently, a solution-ENDOR study of the semiquinone anion from emodic acid (5), an oxidation product of emodin, was reported (Rahimipour et al., 2001b); emodin, a derivative of 9,10-anthraquinone, is used as a laxative and has other pharmacological applications (Hartmann and Goldstein, 1989). Here, we describe solutionENDOR spectra of the semiquinone anion and dianion from hypericin (6H) (Gerson et al., 1995), a derivative of biphenoquinone, which has been isolated from St. John’s wort and displays antiviral, antidepressive, and photodynamic activity (Muldner and Zoller, 1984; Suzuki et al., 1984). Solution-ENDOR spectra of a radical anion and two radical dianions from hypericin derivatives (Rahimipour et al., 2001a) are also presented.

quinone; 4) which is another derivative of 1,4-naphthoquinone. Recently, a solution-ENDOR study of the semiquinone anion from emodic acid (5), an oxidation product of emodin, was reported (Rahimipour et al., 2001b); emodin, a derivative of 9,10-anthraquinone, is used as a laxative and has other pharmacological applications (Hartmann and Goldstein, 1989). Here, we describe solutionENDOR spectra of the semiquinone anion and dianion from hypericin (6H) (Gerson et al., 1995), a derivative of biphenoquinone, which has been isolated from St. John’s wort and displays antiviral, antidepressive, and photodynamic activity (Muldner and Zoller, 1984; Suzuki et al., 1984). Solution-ENDOR spectra of a radical anion and two radical dianions from hypericin derivatives (Rahimipour et al., 2001a) are also presented.

2.2Hypericin

Hypericin is claimed to exist as 7,14and 1,6-dihydroxy tautomers, of which the former (6H) is more stable and prevails in non-concentrated solutions (Dax et al., 1999; Etzlstorfer and Falk, 2000; Freeman et al., 2001). In neutral and alkaline media, it readily deprotonates to yield its conjugate base  Both 6H and

Both 6H and readily accept an additional electron, and ENDOR spectroscopy serves as a straightforward tool to find out whether deprotonation also occurs at the stage of the one-electron-reduced species.

readily accept an additional electron, and ENDOR spectroscopy serves as a straightforward tool to find out whether deprotonation also occurs at the stage of the one-electron-reduced species.

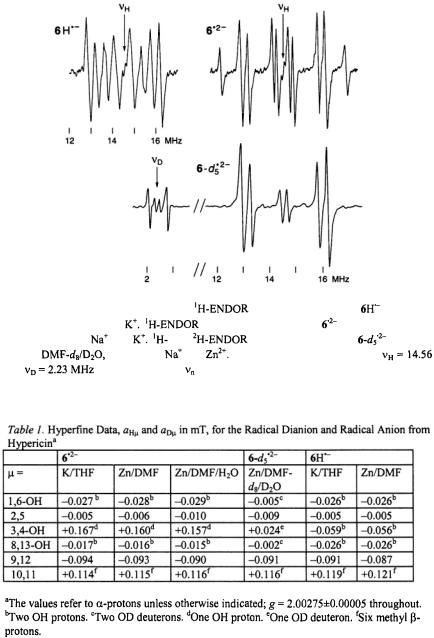

Figure 4 shows the  spectrum of the radical dianion

spectrum of the radical dianion  generated from the sodium salt of

generated from the sodium salt of  with potassium in tetrahydrofuran (THF); identical spectra were observed under the same conditions from other salts of

with potassium in tetrahydrofuran (THF); identical spectra were observed under the same conditions from other salts of  and very similar ones were obtained upon reduction of the sodium salt with zinc in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and

and very similar ones were obtained upon reduction of the sodium salt with zinc in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and

(10:1) (Gerson et al., 1995). Use of  (10:1) led to the radical dianion

(10:1) led to the radical dianion  in which all five OH protons were replaced by deuterons; the pertinent

in which all five OH protons were replaced by deuterons; the pertinent  and

and  spectra are also reproduced in Figure 4. Contrary to the EPR and ENDOR spectra of the persistent radical dianion

spectra are also reproduced in Figure 4. Contrary to the EPR and ENDOR spectra of the persistent radical dianion  those of the radical anion

those of the radical anion  its conjugated acid, were observable only under strictly anhydrous conditions, because

its conjugated acid, were observable only under strictly anhydrous conditions, because  rapidly deprotonated

rapidly deprotonated

to  in the presence of traces of water. A

in the presence of traces of water. A  spectrum of

spectrum of  recorded immediately upon reaction of 6H with potassium in a carefully dried THF, is likewise displayed in Figure 4.

recorded immediately upon reaction of 6H with potassium in a carefully dried THF, is likewise displayed in Figure 4.

154 |

FABIAN GERSON AND GEORG GESCHEIDT |

Figure 4. Radical |

ions from hypericin. |

|

spectrum of the |

anion |

(top, left); |

|

solvent THF, counterion |

|

|

spectrum of the dianion |

(top, |

right); solvent |

|

THF, counterions |

and |

and |

|

spectra of the dianion |

(bottom); |

|

solvent |

counterions |

and |

Temperature 298 K throughout. |

|||

and |

are the frequencies |

of the free proton and deuteron, respectively. Taken |

||||

with a Bruker-ESP-300 spectrometer. Reproduced from (Gerson et al., 1995) by permission of J. Am. Chem. Soc.

The hyperfine data for  and

and  obtained under various conditions, are listed in Table 1. Relying on simulation of the EPR spectra of

obtained under various conditions, are listed in Table 1. Relying on simulation of the EPR spectra of

SOLUTION ENDOR OF RADICAL IONS |

155 |

its coupling constants,

its coupling constants,  of one and six protons were straightforwardly assigned to the single proton bridging the 3,4-O atoms and to the

of one and six protons were straightforwardly assigned to the single proton bridging the 3,4-O atoms and to the  of the two 10,11-methyl substituents, respectively. Moreover, deuteration allowed to distinguish the proton pairs in the 1,6- and 8,13-OH groups from the sets of two

of the two 10,11-methyl substituents, respectively. Moreover, deuteration allowed to distinguish the proton pairs in the 1,6- and 8,13-OH groups from the sets of two  at the

at the  and 9,12. (According to the conventional nomenclature of EPR spectroscopy, protons directly linked to the

and 9,12. (According to the conventional nomenclature of EPR spectroscopy, protons directly linked to the  are called

are called  while those separated from such centers by one

while those separated from such centers by one  C atom are denoted

C atom are denoted  The remaining ambiguities were resolved by UB3LYP/6-31G* calculations (Rahimipour et al., 2001a). The coupling constants for

The remaining ambiguities were resolved by UB3LYP/6-31G* calculations (Rahimipour et al., 2001a). The coupling constants for  are similar to those for

are similar to those for  with the exception of the value due to the two protons in the non-dissociated 3,4-OH groups of

with the exception of the value due to the two protons in the non-dissociated 3,4-OH groups of  which strongly differs from that of the single proton bridging the pertinent two O atoms in

which strongly differs from that of the single proton bridging the pertinent two O atoms in  The signs of the coupling constants were determined by the general-TRIPLE-resonance experiments with the reasonable assumption that the values of the

The signs of the coupling constants were determined by the general-TRIPLE-resonance experiments with the reasonable assumption that the values of the  are negative. All signs were confirmed by theoretical calculations. The hyperfine data for

are negative. All signs were confirmed by theoretical calculations. The hyperfine data for  and

and  are compatible with a twisted helical geometry and aneffective

are compatible with a twisted helical geometry and aneffective  symmetry.

symmetry.

2.3Hypericin Derivatives

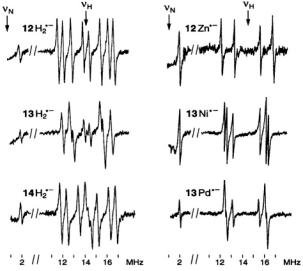

These derivatives are 2,5-dibromohypericin (7H), 10,11desmethylhypericin (8H), and 1,3,4,6,8,13-hexaacetylhypericin (9). In contrast to the parent hypericin (6H), the  of 8H can adopt a planar geometry, while the 3,4-OAc groups of 9 are not amenable to deprotonation. The three compounds were reduced under various experimental conditions (Rahimipour et al., 2001a), and the

of 8H can adopt a planar geometry, while the 3,4-OAc groups of 9 are not amenable to deprotonation. The three compounds were reduced under various experimental conditions (Rahimipour et al., 2001a), and the  spectra of the paramagnetic species thus obtained with zinc in DMF are shown in Figure 5. These spectra allowed to identify the species in question as the radical dianions

spectra of the paramagnetic species thus obtained with zinc in DMF are shown in Figure 5. These spectra allowed to identify the species in question as the radical dianions  and

and  and the radical anion

and the radical anion  respectively. Their hyperfine data are given in Table 2.

respectively. Their hyperfine data are given in Table 2.

156 |

FABIAN GERSON AND GEORG GESCHEIDT |

Figure 5. Radical ions from hypericin derivatives.  spectra of the dianions

spectra of the dianions  (top) and

(top) and  (left, bottom) and of the anion

(left, bottom) and of the anion  (right, bottom); solvent DMF, counterion

(right, bottom); solvent DMF, counterion  , temperature 273 K.

, temperature 273 K.  is the frequency

is the frequency  of the free proton. The unsplit signals at

of the free proton. The unsplit signals at  in the spectra of

in the spectra of  and

and  arise from protons with a very small coupling constant; the pertinent (absolute) values are 0.003 mT for 1,6-OH protons in

arise from protons with a very small coupling constant; the pertinent (absolute) values are 0.003 mT for 1,6-OH protons in  (Table 2) and <0.005 mT for the acetyl protons in

(Table 2) and <0.005 mT for the acetyl protons in  (not given in Table 2). Taken with a Bruker-ESP-300 spectrometer. Reproduced from (Rahimipour et al., 2001a) by permission of Photochem. Photobiol.

(not given in Table 2). Taken with a Bruker-ESP-300 spectrometer. Reproduced from (Rahimipour et al., 2001a) by permission of Photochem. Photobiol.

Assignments and signs of the coupling constants  which compare favorably with the corresponding values for

which compare favorably with the corresponding values for  and

and  were corroborated by UB3LYP/6-31G* calculations. The spin distribution in these radical dianions and radical anion is not markedly altered by the structural modifications of hypericin, as the bulk of spin population remains accommodated by the central biphenoquinone moiety. With respect to

were corroborated by UB3LYP/6-31G* calculations. The spin distribution in these radical dianions and radical anion is not markedly altered by the structural modifications of hypericin, as the bulk of spin population remains accommodated by the central biphenoquinone moiety. With respect to

SOLUTION ENDOR OF RADICAL IONS |

157 |

biological processes it is important to note that the structure of like that of

like that of  remains unaltered when organic solvents are replaced by an aqueous buffer solution.

remains unaltered when organic solvents are replaced by an aqueous buffer solution.

3.PORPHYRINOIDS

3.1Introduction

Porphyrins in general, and metalloporphyrins in particular, are involved in many biological processes and, owing to their deep colors, have been called the pigments of life (Battersby and McDonald, 1979; Battersby and Frobel, 1982). The prominent property of these macrocyclic  is the easy acceptance and donation of electrons, which leads to many redox stages. Because of their effective

is the easy acceptance and donation of electrons, which leads to many redox stages. Because of their effective  symmetry, the radical ions of the unsubstituted porphyrin

symmetry, the radical ions of the unsubstituted porphyrin  and metalloporphyrins (10M) (Seth and Bocian, 1994), as well as those of tetraoxaporphyrin (11) (Bachmann et al., 1992; Bachmann, 1996), have a degenerate ground state and are subject to the dynamic Jahn-Teller effect which enhances the electron-spin relaxation. As a consequence, the EPR lines of these ions are excessively broadened and difficult to saturate, so that their solution-ENDOR spectra could not be observed. On the other hand, the effective symmetry is lowered to

and metalloporphyrins (10M) (Seth and Bocian, 1994), as well as those of tetraoxaporphyrin (11) (Bachmann et al., 1992; Bachmann, 1996), have a degenerate ground state and are subject to the dynamic Jahn-Teller effect which enhances the electron-spin relaxation. As a consequence, the EPR lines of these ions are excessively broadened and difficult to saturate, so that their solution-ENDOR spectra could not be observed. On the other hand, the effective symmetry is lowered to  in the isomeric porphycene

in the isomeric porphycene  (Vogel et al., 1986), metalloporphycenes (12M), and tetraoxaporphycene (15) (Vogel et al., 1988) which also have

(Vogel et al., 1986), metalloporphycenes (12M), and tetraoxaporphycene (15) (Vogel et al., 1988) which also have

158 |

FABIAN GERSON AND GEORG GESCHEIDT |

applications to photobiology (Toporowicz et al., 1989). The corresponding radical ions have thus a nondegenerate ground state, and they gave rise to highly resolved EPR spectra along with readily observable solution-ENDOR signals (Schlüpmann et al., 1990; Bachmann et al., 1993; Bachmann, 1996), as is described below.

3.2Porphycenes and Metalloporphycenes

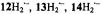

The porphycenes, of which the radical anions were studied, include the free base  and its 2,7,12,17and 9,10,19,20-tetra-n-propyl derivatives

and its 2,7,12,17and 9,10,19,20-tetra-n-propyl derivatives  and

and  respectively), as well the metalloporphycenes 12Zn, 13Ni, 13Pd, and 13Pt (Schlüpmann et al., 1990).

respectively), as well the metalloporphycenes 12Zn, 13Ni, 13Pd, and 13Pt (Schlüpmann et al., 1990).

Figure 6. Radical ions of porphycenes and metalloporphycenes.  and

and  spectra of the anions

spectra of the anions  (left, from top to bottom) and

(left, from top to bottom) and  and

and  (right, from top to bottom); solvent THF, counterion

(right, from top to bottom); solvent THF, counterion  temperature 220–240 K.

temperature 220–240 K.  and

and are the frequencies

are the frequencies  of the free proton and

of the free proton and  nucleus, respectively. For the

nucleus, respectively. For the  constant,

constant,  the low-frequency signal at 0.04 MHz was not observed, because it is below the range of the spectrometer. Taken with a home-built instrument. Reproduced from (Schlüpmann et al., 1990) by permission of J. Am. Chem. Soc.

the low-frequency signal at 0.04 MHz was not observed, because it is below the range of the spectrometer. Taken with a home-built instrument. Reproduced from (Schlüpmann et al., 1990) by permission of J. Am. Chem. Soc.

Figure 6 presents the  and

and  spectra of the corresponding radical anions (except those of

spectra of the corresponding radical anions (except those of  which were generated from their neutral precursors with sodium in THF. The MW power required for saturation of the EPR line, a prerequisite for a successful ENDOR experiment, had to be raised on going from

which were generated from their neutral precursors with sodium in THF. The MW power required for saturation of the EPR line, a prerequisite for a successful ENDOR experiment, had to be raised on going from  to

to  and to

and to  ENDOR signals of

ENDOR signals of  were not detected even with the MW power as

were not detected even with the MW power as

SOLUTION ENDOR OF RADICAL IONS |

159 |

high as 200 mW. The increased reluctance to saturation is a consequence of the more efficient spin-orbit coupling and the enhanced electron-spin relaxation with the growing atomic order of the metal. This phenomenon was also manifested by the broadening of the EPR lines (that of  is a single unresolved signal) and the higher g factor, as indicated in Table 3 which gives the hyperfine data for the six radical anions with observable

is a single unresolved signal) and the higher g factor, as indicated in Table 3 which gives the hyperfine data for the six radical anions with observable  and

and  constants,

constants,  and

and

The  and

and  values are compatible with the symmetry

values are compatible with the symmetry  being effective on the hyperfine time-scale, especially with the equivalency of the four

being effective on the hyperfine time-scale, especially with the equivalency of the four  nuclei and the fast tautomerization of the two N-protons in

nuclei and the fast tautomerization of the two N-protons in

and

and  Assignments of the coupling constants

Assignments of the coupling constants  relied (i) on special-TRIPLE-resonance experiments and simulation of the EPR spectra, from which the numbers of protons giving rise to the ENDOR signals were derived, (ii) on deuteration in the 9,10,19,20-positions of

relied (i) on special-TRIPLE-resonance experiments and simulation of the EPR spectra, from which the numbers of protons giving rise to the ENDOR signals were derived, (ii) on deuteration in the 9,10,19,20-positions of  (Renner et al., 1989), and (iii) on the internal consistency of the hyperfine data in the series, by which sets with equal numbers of protons were distinguished. The relative signs of all coupling constants were derived from the general- TRIPLE-resonance spectra with the reasonable assumption that the values of the

(Renner et al., 1989), and (iii) on the internal consistency of the hyperfine data in the series, by which sets with equal numbers of protons were distinguished. The relative signs of all coupling constants were derived from the general- TRIPLE-resonance spectra with the reasonable assumption that the values of the  are negative. Both assignments and signs of the coupling constants were confirmed by all-valence-electrons-self-consistent-field MO calculations (RHF/INDO-/SP) for

are negative. Both assignments and signs of the coupling constants were confirmed by all-valence-electrons-self-consistent-field MO calculations (RHF/INDO-/SP) for  and

and  The changes in the

The changes in the  distribution along the series are moderate, and metallation has only a minor effect. On going from

distribution along the series are moderate, and metallation has only a minor effect. On going from to

to  and from

and from  to

to  or

or  there is an increase in the

there is an increase in the  populations

populations  at the centers

at the centers

and a corresponding decrease at

and a corresponding decrease at  and 9,10,19,20.

and 9,10,19,20.