Власть, бизнес, общество в регионах неправильный треугольник - Петров Н., Титков А. (ред

.).pdf

личной активности тех, кто не смог попасть в Законодательное собрание. Наиболее типичный пример — председатель палаты А. Костенюк, баллотировавшийся в ЗС по одномандатному округу, но проигравший. Однако в отличие от ЗС Общественная палата не обладает ни полномочиями, ни влиянием на общественную жизнь.

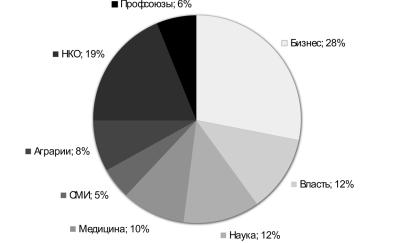

Состав Общественной палаты подтверждает гипотезу о «втором парламенте». Наибольшую долю в ее структуре составляют представители бизнеса — 28% (рис. 2.12). И только на втором месте находятся активисты некоммерческих организаций традиционного спектра (инвалидов, ветеранов, женских, национальных и религиозных). В палате не представлены правозащитные и экологические организации, представители власти и научных организаций (аффилированных с властью через цепочки бюджетного финансирования). А зависимые от бюджета аграрии и врачи составляют еще 18% состава палаты.

Рис. 2.12. Структура Общественной палаты Оренбургской области

Налицо клиентелистская суть Общественной палаты. С одной стороны, она обслуживает администрацию области, с другой — губернатор может похвалиться перед Центром, что идет «в ногу с решениями президента». Кроме того (и в этом проявляется региональная специфика), Общественная палата канализирует амбиции региональной элиты второго эшелона.

Оренбургское

отделение Комитета против пыток

Вячеслав Дюндин

Эффективность деятельности прокуратуры в области защиты прав человека — один из главных факторов, характеризующих положение в этой сфере. Общественные организации, специализирующиеся в области защиты прав человека, полномочны лишь оценить уровень эффективности работы прокуратуры и оказать помощь гражданам, не нашедшим там помощи.

Одной из них является Комитет против пыток, основанный в 2000 г. Комитет имеет статус межрегиональной общественной организации. Его штаб-квартира находится в Нижнем Новгороде, представительства действуют в Чечне, Марий Эл и Башкирии. Кроме того, комитет имеет отделение в Оренбургской области.

Задачи комитета — общественный контроль за применением пыток и жестоким обращением в России и профессиональная юридическая и медицинская помощь жертвам пыток.

Методика общественного расследования по жалобам на применение пыток и жестокого обращения — собственная уникальная разработка Комитета против пыток. В рамках общественного расследования юристы комитета проводят самостоятельное независимое расследование, результаты которого используются как допустимые доказательства в рамках официального следствия, а затем в судебном процессе.

3 . О Б Щ Е С Т В О |

431 |

За время работы специалисты комитета получили и проверили около 700 заявлений о нарушениях прав человека (из них более 80 от жителей Оренбургской области), провели сотни расследований, добились от государства и его представителей выплаты многомиллионных (в Оренбургской области — 200 тыс. руб.) компенсаций гражданам, пострадавшим от незаконных действий правоохранительных органов. В результате усилий юристов комитета по дошедшим до суда делам о пытках осуждено более 30 сотрудников правоохранительных органов. Специалисты по европейскому праву комитета подготовили и направили в Европейский суд по правам человека 36 жалоб (из них 4 — в интересах жителей Оренбургской области). По самой известной из них, «Михеев против Российской Федерации», в январе 2006 г. Европейский суд вынес положительное решение, в котором признано нарушение российским государством Европейской конвенции по защите прав человека и основных свобод. Кроме того, в пользу Михеева взыскано с России 250 тыс. евро компенсации. Это крупнейшая компенсация, взысканная Европейским судом с России. Сегодня Комитет против пыток — крупнейшая правозащитная организация страны, специализирующаяся на исследовании проблемы применения пыток, расследовании жалоб на их применение и оказании юридической и медицинской помощи их жертвам.

В заключение — один пример. Для нас очевидно, что правоохранительные органы в своей деятельности по раскрытию преступлений используют методику, основанную на применении пыток к подозреваемым в совершении преступлений. Потенциального подозреваемого приглашают для беседы, не имея на то законных оснований, а подчас и серьезных оснований для подозрений. В помещение РОВД «собеседник» попадает мимо окна оперативного дежурного — либо дежурные закрывают глаза на факт доставления человека (во всех подразделениях милиции есть второй вход). Иными словами, человек в такой ситуации «пропал». В большинстве случаев на беседу подозреваемый приглашается в пятницу. Если он упорствует, его могут держать в помещении в «пропавшем» состоянии до утра понедельника, когда только и будет оформлено его доставление. На звонки родственников помощник оперативного дежурного с чистым сердцем отвечает, что в книге доставленных имярек не значится.

S u m m a r y

Over the course of less than two decades, new state structures, new businesses and a new society have been formed in Russia. To a substantial degree, the new players inherited the Soviet system that preceded them and from which the current Russian system has evolved. These players possess a number of peculiarities, stemming from the ways in which institutions, familiar in many other countries, have been adapted to Russian conditions, and from the strictly Russian “inventions” that arose over the course of a protracted and complex political, economic, and social evolution. Different parts of the system developed at varied and constantly changing speeds and at times changed course altogether. While these transformations were taking place, society, government and business remained tightly interconnected, each acting at times as the driving force, and at other times as the object of the tectonic changes under way.

This evolution gave rise to a highly complex, varied, and often internally contradictory system, difficulties compounded by the fact that, for a significant part of post-Soviet Russian history, the socio-political and economic transformations in each of the various parts of the vast and heterogeneous country proceeded differently. Thus, alongside radical changes to the system in general, there also emerged an agglomeration of regional subsystems that in many ways developed autonomously.

S U M M A R Y |

433 |

A number of these systems maintain to this day not only fundamental individual peculiarities, but also a certain independence within the framework of the Russian system as a whole. Precisely for this reason, studying this picture on the regional level has a heuristic significance of its own.

The book contains the results of the first stage of a new, large-scale research project involving the multidimensional study of the relationships between society, government and business in Russia’s regions. Launched in the fall of 2006, the project continues the socio-economic and political regional studies carried out by the Carnegie Moscow Center in the mid1990s. In recent years, with the country’s emergence from the crisis of the 1990s, political stabilization, the conclusion of the post-Soviet period and the transition to a fundamentally new stage of development, serious changes began to appear in most of the regions. This new project aims to identify and analyze these changes and to evaluate the current state of the interrelations between government, business and society, and the problems of and prospects for development.

As an immediate object of study, we chose 10-15 of Russia’s current 83 regions, primarily from among the important functional centers of the fuel and energy industry that has played – and continues to play – a key role in the new stage of the country’s development. These regions are involved in the extraction, transportation and processing of hydrocarbons. They represent different geographical and economic models, and differ in size, character of political and economic organization, and level and dynamics of development. The sample as a whole makes up between a fifth and a sixth of the country’s regions and is representative of Russia as a whole.

The first region in our study was Irkutsk, which in October 2006 hosted a series of Carnegie Moscow Center seminars involving local scholars, officials and representatives from business and civil society. In March 2007, a similar trip on a somewhat condensed schedule took place in the Murmansk region; in September 2007, there was a trip to the Astrakhan region; and in March 2008, a study was conducted in the Orenburg region. Aside from the trips to the regions themselves, work was also carried out with experts in Moscow through seminars, working group meetings and individual conversations with experts both before and after the field trips.

The topics analyzed included: general patterns and regional peculiarities in the development of the political system and of business; the

434 |

S U M M A R Y |

organization of power in the regions on regional and municipal levels; development strategies of both the regions themselves and of the regions’ major corporations; the composition and means of the growth and development of the political and business elite; the evolution of the region’s military elite and their role in the development of the region; the influence of the federal government on the processes of regional development; social responsibility in the business world, including when implemented in the form of agreements about social partnership; the state of civil society and the situation with respect to democracy. The main focus was on relationships within the framework of the “state-business-society” triangle as a whole, as well as bilateral ties between each of the “vertices:” government and business, society and government, and business and society.

The financial and economic crisis that broke out in the fall of 2008 lends a particular interest and importance to the study carried out on the basis of four regions. With the crisis, a significant stage in the country’s economic and socio-political development ended. The “years of plenty” had come to a close, together with the prevailing model of relations between government, business and society, which had reflected a situation in which the economic “pie” was constantly growing for elites, as well as for average citizens. Consequently, the portraits of the regions presented here – both as a group and individually – are, in a way, a final pre-crisis photograph, the main characters of which do not yet know that “tomorrow there will be a crisis.”

Research has shown that, despite certain regional variations, relationships in the tripartite format of “state-business-society” are practically nonexistent. First and foremost, there exist bilateral relations between the vertices of the triangle: government with business, government with society, and society with business. In all of these relationships, the government plays the most active and assertive role, as they possess the ability both to set the terms of the dialogue and control who can participate. Business occupies a more passive position, but has the ability to interact with the authorities on its own initiative and has the appropriate channels for doing so. There are no forums for dialogue between authorities and society on the initiative of the latter, with the exception of extreme events, such as protests against one or another of the authorities’ actions. With the onset of the crisis, this is becoming an especially significant structural shortcoming of the system.

S U M M A R Y |

435 |

The vertices of the “state – business – society” triangle appear to be consolidated to varying degrees, and their interests are analyzed, formulated and articulated in different ways. Authorities appear to be the most consolidated of the three, although in its case one must differentiate the position of the authorities as such (given all the possible divergences in the positions of their various levels and segments) from the positions of their individual representatives, as well as from separate groups within the state apparatus who are connected with one or another business clan. As concerns business, one must differentiate between the interests of various corporations, which are better represented, and the common interests of all corporations, which are less represented. Society, meanwhile, is seen to behave more as an object than the subject of action. It is characterized by passivity and paternalism in relation to the state and business and pursues interests that are private (rather than collective) and weakly articulated. The absence of universally recognized spokespersons to voice common interests, and the appropriation by various groups of the right to express common interests, compounds the situation.

What resources and capabilities do the state, business and society possess? Government officials command all the power and resources of the state: its mechanisms of repression and its ability to both define the rules of the game and to enforce them, including the potential to enforce them selectively. Business has the financial resources and the possibility of exerting corporate pressure on the authorities both as a whole, and individually on the authorities’ representatives, with the goal of obtaining desired outcomes. Society, besides having public opinion at its disposal – which in theory can be manipulated both by authorities and by business in their own respective interests – also has tremendous social energy in reserve. The problem with this energy is that, for now, it is used with very little efficacy and for the most part toward destructive ends. Society faces the task of mastering the mechanisms of the management of social energy, as in a thermonuclear reaction. Coordinated actions on the part of society, if they succeed, can present a significant constructive force.

The state, occupying the dominant position in the triangle and in the absence of proper vertical and horizontal separations and periodic jolts in the form of elections, tends to establish informal symbiotic and parasitic relationships with the other actors. In recent years, the relationship between government and business has become more institutionalized and the mechanisms by which they interacted have been con-

436 |

S U M M A R Y |

structed from both sides. As regards the relationship between business and society, institutionalization is either entirely absent, or those institutional elements that may have appeared at one time have since been dismantled. The state has actively interfered in the matter and, under the flag of “socially responsible business,” became an intermediary, determining what society needed and imposing a sort of “social tax” on business. The latter not only promotes corruption – both conventional and political – and feeds paternalistic attitudes in society, but also saps the desire and resources of business to establish a direct relationship with society.

Various business associations act as platforms for interaction between the state and business: the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, the Russian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Opora and Delovaya Rossiya. All of these venues were to some degree established by business, or at least with the participation of business, but are nevertheless controlled by government, which moderates the dialogue between itself and business. Questions regarding the relationship between business and society are discussed within the confines of these venues. There are practically no forums for interaction between business and society without the involvement of the state.

Federal and regional authorities have created several platforms for interacting with business, including various councils chaired the regional governor (on entrepreneurship, on the development of small and medium business, etc.). Likewise, various sorts of political advisory councils, public councils and public chambers have been created for interaction with society. In many such regional forms, as well as in the analogous structures on the federal level, representatives of the business community are also present: both as spokespersons for the interests of a given social group (albeit not necessarily a large one) and as sponsors. There are also less strictly regulated versions of these venues, such as public hearings, for example.

In the realm of state-society relations, the old avenues of interaction, such as elections and political parties, have been eviscerated. Elections in themselves represent the “correct” self-regulating model for the interaction of authorities, business and society. This model, indisputably, has shortcomings, but given public scrutiny and transparency, even if only partial, these shortcomings are evident and surmountable. Any other model, including the one currently implemented, in which regional

S U M M A R Y |

437 |

governors are appointed, and given insufficient division of powers and the weakness and lack of independence of political parties, turns into a loosely structured deal between authorities and business and is fraught with far more serious political costs.

The old platforms for state-society interaction are being replaced by new ones, including public chambers and councils and various public “complaint offices,” which in many respects only imitate direct communication. In these new formats, the initiative overwhelmingly belongs to government, while society plays a passive role. The authorities do this for their own convenience, displaying a myopia that is especially dangerous in the face of the developing crisis. Reducing public oversight of the state and weakening the channels of feedback between state and society contributes to a reduction in the efficiency of government itself and strengthens the potential for conflict, as well as heightens the potential risks and scale of conflicts. The existing mechanisms for resolving conflicts between the state and business – which are settled, as a rule, on an individual basis by business appealing to a higher rank authority – are not sufficiently effective.

What are the main problems of cooperation for each of the sides concerned? The authorities are wholly focused on their relationship with higher levels of government and see business either as belonging to themselves or as a cash cow for their own projects, including in regard to society, with which the government has a paternalistic relationship. Business, on the one hand, is the most independent and self-sufficient of the three, but on the other hand, is highly dependent on the state; for business, the relationship with society is seen either as a compulsory service imposed by government, or as a whim and a form of self-expression, but not as a partnership. Society is alienated and trusts neither government, business, nor its own representatives; it is the least structured of all and is poorly adapted to any forms of non-mass collective action. Society’s lack of independence and the state‘s habit of paternalism encourages society to appeal to government for a solution to its own, internal problems, as well as to the problems of its relations with business.

О Ф о н д е К а р н е г и

Фонд Карнеги за Международный Мир является неправительственной, внепартийной, некоммерческой организацией со штаб-квартирой в Вашингтоне (США). Фонд был основан в 1910 г. известным предпринимателем и общественным деятелем Эндрю Карнеги для проведения независимых исследований в области международных отношений. Фонд не занимается предоставлением грантов (стипендий) или иных видов финансирования. Деятельность Фонда Карнеги заключается в выполнении намеченных его специалистами программ исследований, организации дискуссий, подготовке и выпуске тематических изданий, информировании широкой общественности по различным вопросам внешней политики и международных отношений.

Сотрудниками Фонда Карнеги за Международный Мир являются эксперты мирового уровня, которые используют свой богатый опыт в различных областях, накопленный ими за годы работы в государственных учреждениях, средствах массовой информации, университетах и научно-исследовательских институтах, международных организациях. Фонд не представляет точку зрения какого-либо правительства, не стоит на какой-либо идеологической или политической платформе, и его сотрудники имеют самые различные позиции и взгляды.

Решение создать Московский Центр Карнеги было принято весной 1992 г. с целью реализации широких перспектив сотрудничества, которые открылись перед научными и общественными кругами США, России и новых независимых государств после окончания периода «холодной войны». С 1994 г. в рамках программы по России и Евразии, реализуемой одновременно в Вашингтоне и Москве, Центр Карнеги осуществляет широкий спектр общественно-поли-тических и со- циально-экономических исследований, организует открытые дискуссии, ведет издательскую деятельность.

Основу деятельности Московского Центра Карнеги составляют публикации и циклы семинаров по внутренней и внешней политике России, по проблемам нераспространения ядерных и обычных вооружений, российско-американских отношений, безопасности, гражданского общества, а также политических и экономических преобразований на постсоветском пространстве.

CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT |

МОСКОВСКИЙ |

FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE |

ЦЕНТР КАРНЕГИ |

1779 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Washington, |

Россия, 125009, Москва, |

DC 20036, USA |

Тверская ул., 16/2 |

Tel.: +1 (202) 483-7600; |

Тел.: +7 (495) 935-8904; |

Fax: +1 (202) 483-1840 |

Факс: +7 (495) 935-8906 |

E-mail: info@CarnegieEndowment.org |

E-mail: info@сarnegie.ru |

http://www.CarnegieEndowment.org |

http://www.carnegie.ru |