- •Preface

- •Acronyms

- •Introduction

- •Background and objectives

- •Content, format and presentation

- •Radioactive waste management in context

- •Waste sources and classification

- •Introduction

- •Radioactive waste

- •Waste classification

- •Origins of radioactive waste

- •Nuclear fuel cycle

- •Mining

- •Fuel production

- •Reactor operation

- •Reprocessing

- •Reactor decommissioning

- •Medicine, industry and research

- •Medicine

- •Industry

- •Research

- •Military wastes

- •Conditioning of radioactive wastes

- •Treatment

- •Compaction

- •Incineration

- •Conditioning

- •Cementation

- •Bituminisation

- •Resin

- •Vitrification

- •Spent fuel

- •Process qualification/product quality

- •Volumes of waste

- •Inventories

- •Inventory types

- •Types of data recorded

- •Radiological data

- •Chemical data

- •Physical data

- •Secondary data

- •Radionuclides occurring in the nuclear fuel cycle

- •Simplifying the number of waste types

- •Radionuclide inventory priorities

- •Material priorities

- •Inventory evolution

- •Assumptions

- •Errors

- •Uncertainties

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Development of geological disposal concepts

- •Introduction

- •Historical evolution of geological disposal concepts

- •Geological disposal

- •Definitions and comparison with near-surface disposal

- •Development of geological disposal concepts

- •Roles of the geosphere in disposal options

- •Physical stability

- •Hydrogeology

- •Geochemistry

- •Overview

- •Alternatives to geological disposal

- •Introduction

- •Politically blocked options: sub-seabed and Antarctic icecap disposal

- •Sea dumping and sub-seabed disposal

- •Antarctic icesheet disposal

- •Technically impractical options; partitioning and transmutation, space disposal and icesheet disposal

- •Partitioning and Transmutation

- •Space disposal

- •Icesheets and permafrost

- •Non-options; long-term surface storage

- •Alternatives to conventional repositories

- •Introduction

- •Alternative geological disposal concepts

- •Utilising existing underground facilities

- •Extended storage options (CARE)

- •Injection into deep aquifers and caverns

- •Deep boreholes

- •Rock melting

- •The international option: technical aspects

- •Alternative concepts: fitting the management option to future boundary conditions

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Site selection and characterisation

- •Introduction

- •Prescriptive/geologically led

- •Sophisticated/advocacy led

- •Pragmatic/technically led

- •Centralised/geologically led

- •Conclusions to be drawn

- •Lessons to be learned (see Table 4.2)

- •Site characterisation

- •Can we define the natural environment sufficiently thoroughly?

- •Sedimentary environments

- •Hydrogeology

- •The regional hydrogeological model

- •More local hydrogeological model(s)

- •Crystalline rock environments

- •Lithology and structure

- •Hydrogeology

- •Hydrogeochemistry

- •Any geological environment

- •References

- •Repository design

- •Introduction: general framework of the design process

- •Identification of design requirements/constraints

- •Concept development

- •Major components of the disposal system and safety functions

- •A structured approach for concept development

- •Detailed design/specifications of subsystems

- •Near-field processes and design issues

- •Design approach and methodologies

- •Design confirmation and demonstration

- •Interaction with PA/SA

- •Demonstration and QA

- •Repository management

- •Future perspectives

- •References

- •Assessment of the safety and performance of a radioactive waste repository

- •Introduction

- •The role of SA and the safety case in decision-making

- •SA tasks

- •System description

- •Identification of scenarios and cases for analysis

- •Consequence analysis

- •Timescales for evaluation

- •Constructing and presenting a safety case

- •References

- •Repository implementation

- •Legal and regulatory framework; organisational structures

- •Waste management strategies

- •The need for a clear policy and strategy

- •Timetables vary widely

- •Activities in development of a geological repository

- •Concept development

- •Siting

- •Repository design

- •Licensing

- •Construction

- •Operation

- •Monitoring

- •Research and development

- •The staging process

- •Attributes of adaptive staging

- •The decision-making process

- •Status of geological disposal programmes

- •Overview

- •Status of geological disposal projects in selected countries

- •International repositories

- •Costs and financing

- •Cost estimates

- •Financing

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Research and development infrastructure

- •Introduction: Management of research and development

- •Drivers for research and development

- •Organisation of R&D

- •R&D in specialised (nuclear) facilities

- •Introduction

- •Inventory

- •Release of radionuclides from waste forms

- •Solubility and sorption

- •Waste form dissolution

- •Colloids

- •Organic degradation products

- •Gas generation

- •Conventional R&D

- •Engineered barriers

- •Corrosion

- •Buffer and backfill materials

- •Container fabrication

- •Natural barriers

- •Geochemistry and groundwater flow

- •Gas transport and two-phase flow

- •Biosphere

- •Radionuclide concentration and dispersion in the biosphere

- •Climate change

- •Landscape change

- •Underground rock laboratories

- •URLs in sediments

- •Nature’s laboratories: studies of the natural environment

- •General

- •Corrosion

- •Cement

- •Clay materials

- •Degradation of organic materials

- •Glass corrosion

- •Radionuclide migration

- •Model and database development

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Building confidence in the safe disposal of radioactive waste

- •Growing nuclear concerns

- •Communication systems in waste management programmes

- •The Swiss programme

- •The Japanese programme

- •Examples of communication styles in other countries

- •Finland

- •Sweden

- •France

- •United Kingdom

- •Comparisons between communication styles in Finland, France, Sweden and the United Kingdom

- •Lessons for the future

- •What is the way forward?

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •A look to the future

- •Introduction

- •Current trends in repository programmes

- •Priorities for future efforts

- •Waste characterisation

- •Operational safety

- •Emplacement technologies

- •Knowledge management

- •Alternative designs and optimisation processes

- •Materials technology

- •Novel construction/immobilisation materials: the example of low pH cement

- •Future SA code development

- •Implications for environmental protection: disposal of other wastes

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Index

230 |

J.M. West and L.E. McKinley |

9.4. Communication systems in waste management programmes

In this section, on Switzerland and Japan, it will be apparent to the reader that there are effectively no references. This is because much of the material discussed is not published in the open literature as such, unlike the situation in, e.g., Sweden and Finland. The websites of both organisations in question (Nagra, www.nagra.ch; NUMO, www.numo.or.jp) do, however, offer a wide range of brochures and other materials.

9.4.1. The Swiss programme

Switzerland has five operating nuclear power plants, producing around 40 per cent of its energy requirements. The five plants are concentrated in the northern, German-speaking part of Switzerland in densely populated regions. Most are also fairly close to the national border with Germany. The Swiss waste management concept currently foresees two types of repository, one for L/ILW and one for HLW/SF/MOX and ILW1. Both are deep geological facilities that can be closed definitively and will have the ability to ensure passive long-term safety thereafter. The Swiss implementer, Nagra, was established in 1972, with responsibility for the disposal of all radioactive waste streams arising in the country.

With its federal structure, made up of 26 states or Cantons and around 2900 local communities or municipalities (‘‘Gemeinde’’), Switzerland has a tradition of formalised, direct involvement of the public in decision-making processes on all political levels. This is also true in the case of radioactive waste management, e.g., in the licensing procedure for nuclear facilities (including a repository).

Set in this environment, Nagra has long recognised the importance of communication with the public throughout all stages of a waste management programme. The most challenging area of all, however, is considered to be site selection, as this involves the most direct contact with a wide range of stakeholders. Nagra’s approach to communication on a nationwide level is considered briefly, followed by more detailed consideration of experience at a local level as part of a site selection procedure.

Over the years, Nagra has built up an open and transparent communication strategy based on a series of core messages. These include the key concepts that are to be communicated to the public such as:

There is a waste problem to be solved;

All of us, irrespective of whether we are for or against nuclear power, have an ethical responsibility to solve this problem;

The required safe disposal technologies are already available.

Other messages are designed to define Nagra’s position and enhance its credibility:

Nagra is a national competence centre, and an internationally recognised partner, in the field of radioactive waste management;

Nagra’s core values include openness, ethical responsibility and technical excellence;

Nagra is a politically neutral organisation working on a task assigned to it by the Swiss government.

1Note that the new Nuclear Energy Act, which became law in February, 2005 also explicitly mentions the possibility of a combined repository for all waste types.

Building confidence in the safe disposal of radioactive waste |

231 |

To communicate these messages on a national level, Nagra uses a wide range of tools, including print products, electronic media, media conferences and releases, videos, CD/DVD, websites (www.nagra.ch; www.grimsel.com), advertising campaigns, exhibitions, information tours and public events.

In recent years, Nagra has conducted a nationwide information campaign aimed at reaching as many of the public as possible with their key messages. The slogan for the campaign is ‘‘Switzerland has radioactive waste. We are taking care of it. Nagra – who else?’’ Nagra staff have taken to the streets of the nation’s many cities to present an informative exhibition based around a series of conventional waste containers (Fig. 9.1), with the overall objective of demonstrating openness to dialogue and technical competence. Using Nagra personnel presents a human face to the public, who can actively engage with the otherwise faceless experts.

At the end of 2003, in the wake of two information campaigns, a poll was conducted to assess public opinion on radioactive waste management issues. Key results include the following:

Fifty-five per cent of the population had heard of Nagra and 73 per cent found it positive that Nagra existed;

Thirty-nine per cent believed that Nagra has an open information policy;

Eighty-three per cent felt that the waste management issue should be solved as quickly as possible and Sixty-one per cent believed that technical solutions already exist;

Twenty-seven per cent had heard of the Nagra information campaign and 3 per cent (equivalent to 210,000 citizens) stated that they had visited the exhibition.

Fig. 9.1. Nagra’s national confidence-building campaign is based on simple images and slogans (image courtesy of Nagra).

232 |

J.M. West and L.E. McKinley |

On a national level, it can thus be said that the need for Nagra and a solution to the waste management problem appears not to be a disputed issue. However, these results do not specifically confirm that there is public confidence in Switzerland in geological disposal of waste.

On a local level, the situation in Switzerland is probably best demonstrated by the Wellenberg experience. The search for a potential site for a repository for L/ILW was broadly based (starting with more than 100 potential sites – see details in Chapters 4 and 7) and was conducted in a scientifically transparent manner. Despite early efforts to communicate with the people at potential sites, some strong opposition was encountered. Following a lengthy narrowing-down procedure, Wellenberg in Canton Nidwalden was finally proposed as the potential site in 1993. As is normal in Switzerland for major construction projects, a local implementing organisation, GNW, was set up and its headquarters based in the siting community (Wolfenschiessen, Canton Nidwalden) in 1995. Agreements were also concluded between GNW, the local community and the Canton regarding compensation payments. GNW then proceeded to submit an application for a general licence for the repository, provided the results from an exploratory drift excavated first delivered positive results. Given the licensing procedure in Switzerland, as defined by the legislation, it was clear from the outset that it would be very difficult – if not impossible – to proceed with the project if it were opposed by a majority of the cantonal and community voters. Nagra and GNW therefore conducted an intensive information campaign at a local level. It should be noted that the siting community of Wolfenschiessen supported the project throughout its entire duration. Site-specific communication strategies included the following:

Early and direct dialogue with local officials and residents;

Holding open meetings;

Local presence (offices, personnel);

Establishment of working groups involving technical and socio-political experts and members of the community;

Prompt publication and distribution of research results;

Inclusion of opponents in every step of the procedure.

In a referendum held in June 1995, the people of Canton Nidwalden voted, albeit by a narrow majority (47.5–52.5 per cent), against the general licence and the exploratory drift. In terms of reaching the voters and building their confidence, something had clearly gone wrong. Based on an analysis of the voting results and on consultations in a series of working groups, it was felt that modifications to both the disposal concept and the licensing approach would improve the situation. There was an indication of a desire on the part of the people for greater monitoring and retrievability in the concept. It was also felt that asking for both the exploratory drift and the repository licence in one step was too much, the fear being that, if permission for the drift were granted, the repository would proceed irrespective of the results from the investigations. A decision was therefore made to apply first for the exploratory drift concession only and, in terms of the disposal concept, modifications were made to accommodate the apparent public wish for greater monitoring and retrievability. Against this background, an application for a concession for the exploratory drift was submitted at the beginning of 2001. However, in September of the same year, the people of Nidwalden voted against the application for a second time. Although the siting community continued to be in favour of the project,

Building confidence in the safe disposal of radioactive waste |

233 |

general opposition in the Canton was actually stronger than it was in 1995 (57.5 per cent against). Despite every effort to communicate and inform openly and objectively, the project was blocked on a political level (it was never called into question on technical grounds) and the site has since been abandoned.

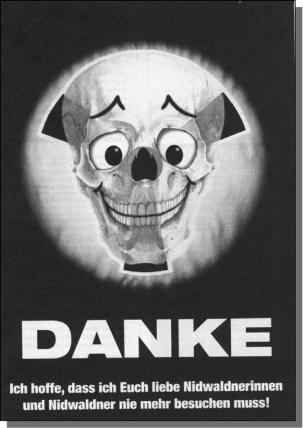

An analysis of the reasons for the second failure provides some lessons for future communication efforts. At the time of the second referendum, there was a general feeling worldwide of uncertainty following the events of 11 September, 2001. On a more local level, contamination of the traditionally ‘‘friendly’’ atmosphere in Nidwalden had been achieved by a long, emotional and aggressive referendum campaign by the opponents. Faced with this very emotional anti-nuclear campaign, with use of powerful and sometimes disturbing images (Fig. 9.2), and a licensing procedure which gave the Canton the power to effectively veto the project, the somewhat dry, factual, unemotional supporters’ campaign (Fig. 9.3) was ultimately unsuccessful in dispelling local distrust and concern. In fact, the phenomenon of voter ‘‘exhaustion’’ probably played a role – by the time the second vote was held, the local people had faced fairly sustained campaigning for nearly a decade if the first vote is included – many just wanted peace and quiet, which would be

Fig. 9.2. An example of the highly emotive material used by the opposition movement at the Wellenberg site (image courtesy of Nagra).

234 |

J.M. West and L.E. McKinley |

Fig. 9.3. An example of the somewhat dry, factual, unemotional supporters’ campaign. The text simply says ‘‘I say yes to the tunnel – no more, no less’’ and refers to the implementer’s request for a licence to build an exploration tunnel to further characterise the site (image courtesy of Nagra).

easier and quicker with a ‘‘no’’ than a ‘‘yes’’. Added to this was the fact that, although there was always approval of the project in the siting community, neighbouring communities felt somewhat excluded from the process, both emotionally and financially. This is not dissimilar to what is often called the ‘‘EuroDisney Effect’’, where communities which are not directly impacted by a major project, but which are near enough to be affected in some manner (be it, as in the EuroDisney case, by extra traffic or, in Nidwalden, by potential radioactive contamination), often feel dissatisfied with their lot. There is often jealousy at the perceived unfairness of a compensation system in which only the directly involved communities receive something. EuroDisney has since learned from this mistake by involving wider-flung communities in their dialogue (and compensation). Arguably, the Swiss nuclear industry has also learned: when plans to site the national interim storage facility in the community of Wu¨renlingen (Canton Aargau) were

Building confidence in the safe disposal of radioactive waste |

235 |

announced, moves were immediately made to include the communities immediately neighbouring Wu¨renlingen in both the discussions and the compensation package. The facility – ZWILAG (see www.zwilag.ch for details) – has now been constructed and is operational – without any significant opposition.

In the follow-up to the second referendum, when the Wellenberg site was abandoned, there was a general feeling of anxiety in many parts of Switzerland that Nagra/GNW might simply fall back on sites that had previously been identified as being potentially suitable. To dispel this fear, it was announced that the previously identified sites would no longer be considered. The way forward in the L/ILW programme is now under complete review, with new legal and political boundary conditions applying, and Nagra will submit a proposed L/ILW management programme to the Swiss Federal Government in 2007.

For the HLW programme, Nagra submitted a technical feasibility demonstration project (‘‘Project Opalinus Clay’’) to the Federal Government at the end of 2002. The information activities surrounding this have been fairly intensive, particularly as the area where investigations are focused is very close to the German border (Fig. 9.4). This means that not only Swiss communities and Cantons but also potentially affected German communities have to be involved in the decision-making process.

On a national level, two anti-nuclear initiatives (phasing-out of nuclear power and a moratorium on new power plant construction) were overwhelmingly rejected in a referendum held in May 2003. It seems that the public accept the need for nuclear power, probably because of increasing national demands for energy. With such a positive result, now is an opportune time to capitalise on changing public attitudes and to build public interest and confidence in the ability to dispose of the waste generated from nuclear power. It is also interesting to note, particularly in the wake of the Wellenberg

Fig. 9.4. Aerial view of the investigation area in the Swiss Project Opalinus Clay. The village of Benken (deep borehole site) is in the centre foreground and the river Rhine, forming the border between Switzerland and Germany, can be seen to the left of the photograph (image courtesy of Nagra).