- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

Late Qing | 253

indemnity amounted to 450 million taels to be paid over 39 years. Moreover, the settlement demanded the establishment of permanent guards and the dismantling of forts between Beijing and the sea, a humiliation that made an independent China a mere fiction. In addition, the southern provinces were actually independent during the crisis. These occurrences meant the collapse of the Qing prestige.

After the uprising, Cixi had to declare that she had been misled into war by the conservatives and that the court, neither antiforeign nor antireformist, would promote reforms, a seemingly incredible statement in view of the court’s suppression of the 1898 reform movement. But the Qing court’s antiforeign, conservative nationalism and the reforms undertaken after 1901 were in fact among several competing responses to the shared sense of crisis in early 20th-century China.

Reformist and revolutionist mOvementS at the end of the dynasty

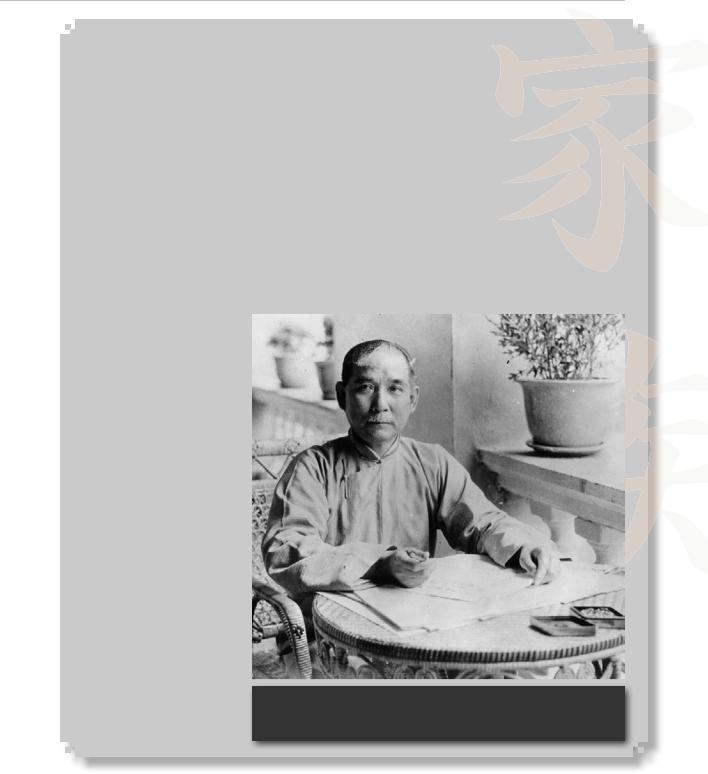

Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan), a commoner with no background of Confucian orthodoxy who was educated in Westernstyle schools in Hawaii and Hong Kong, went to Tianjin in 1894 to meet Li Hongzhang and present a reform program, but he was refused an interview. That event supposedly provoked his antidynastic attitude. Soon he returned to Hawaii, where he founded an anti-Man- chu fraternity called the Revive China

Society (Xingzhonghui). Returning to Hong Kong, he and some friends set up a similar society under the leadership of his associate Yang Quyun. Sun participated in an abortive attempt to capture Guangzhou in 1895, after which he sailed for England and then went to Japan in 1897, where he found much support. Tokyo became the revolutionaries’ principal base of operation.

After the collapse of the Hundred Days of Reform, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao had also fled to Japan. An attempt to reconcile the reformists and the revolutionaries became hopeless by 1900: Sun was slighted as a secret-society ruffian, while the reformists were more influential among the Chinese in Japan and the Japanese.

The two camps competed in collecting funds from the overseas Chinese, as well as in attracting secret-society members on the mainland. The reformists strove to unite with the powerful, secret Society of Brothers and Elders (Gelaohui) in the Yangtze River region. In 1899 Kang’s followers organized the Independence Army (Zilijun) at Hankou in order to plan an uprising, but the scheme ended unsuccessfully. Early in 1900 the Revive China Society revolutionaries also formed a kind of alliance with the Brothers and Elders, called the Revive Han Association. This new body nominated Sun as its leader, a decision that also gave him, for the first time, the leadership of the Revive China Society. The Revive Han Association started an uprising at Huizhou, in Guangdong, in

254 | The History of China

October 1900, which failed after two weeks’ fighting with imperial forces.

After the Boxer disaster, Cixi reluctantly issued a series of reforms, which included abolishing the civil service examination, establishing modern schools, and sending students abroad. But these measures could never repair the damaged imperial prestige; rather, they inspired more anti-Manchu feeling and raised the revolutionary tide. However, other factors also intensified the revolutionary cause: the introduction of social Darwinist ideas by Yen Fu after the Sino-Japanese War countered the reformists’ theory of change based on the Chinese Classics; and Western and revolutionary thoughts came to be easily and widely diffused through a growing number of journals and pamphlets published in Tokyo, Shanghai, and Hong Kong.

Nationalists and revolutionists had their most-enthusiastic and mostnumerous supporters among the Chinese students in Japan, whose numbers increased rapidly between 1900 and 1906. The Zongli Yamen sent 13 students to Japan for the first time in 1896; within a decade the figure had risen to some 8,000. Many of these students began to organize themselves for propaganda and immediate action for the revolutionary cause. In 1902–04, revolutionary and nationalistic organizations—including the Chinese Educational Association, the Society for Revival of China, and the Restoration Society—appeared in Shanghai. The anti-Manchu tract “Revolutionary Army”

was published in 1903, and more than a million copies were issued.

Dealing with the young intellectuals was a new challenge for Sun Yat-sen, who hitherto had concentrated on mobilizing the uncultured secret-society members. He also had to work out some theoretical planks, though he was not a first-class political philosopher. The result of his response was the Three Principles of the People (Sanmin Zhuyi)—nationalism, democracy, and socialism—the prototype of which came to take shape by 1903. He expounded his philosophy in America and Europe during his travels there in 1903–05, returning to Japan in the summer of 1905. The activists in Tokyo joined him to establish a new organization called the United League (Tongmenghui); under Sun’s leadership, the intellectuals increased their importance.

Sun Yat-sen

and the United League

Sun’s leadership in the league was far from undisputed. His understanding that the support of foreign powers was indispensable for Chinese revolution militated against the anti-imperialist trend of the young intellectuals. Only half-heartedly accepted was the principle of people’s livelihood, or socialism, one of his Three Principles. Though his socialism has been evaluated in various ways, it seems certain that it did not reflect the hopes and needs of the commoners.

Ideologically, the league soon fell into disharmony: Zhang Binglin (Chang

Late Qing | 255

Sun yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (Pinyin: Sun Yixian; b. Nov. 12, 1866—d. March 12, 1925), leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party, is known as the father of modern China. Educated in Hawaii and Hong Kong, Sun embarked on a medical career in 1892, but, troubled by the conservative Qing dynasty’s inability to keep China from su«ering repeated humiliations at the hands of more advanced countries, he forsook medicine two years later for politics. A letter to Li Hongzhang in which Sun detailed ways that China could gain strength made no headway, and he went abroad to try organizing expatriate Chinese. He spent time in Hawaii, England, Canada, and Japan and in 1905 became head of a revolutionary coalition, the Tongmenghui (“Alliance Society,” or United League). The revolts he helped plot during this period failed, but in 1911 a rebellion in Wuhan unexpectedly succeeded in overthrowing the provincial government. Other provincial secessions followed, and Sun returned to be elected provisional president of a new government. The emperor abdicated in 1912, and Sun turned over

the government to Yuan Shikai. The two men split in 1913, and Sun became head of a separatist regime in the south. In 1924, aided by Soviet advisers, he reorganized his Nationalist Party, admitted three communists to its central executive committee, and approved the establishment of a military academy, to be headed by Chiang Kai-shek. He also delivered lectures on his doctrine, the Three Principles of the People (nationalism, democracy, and people’s livelihood, or socialism), but died the following year without having had the opportunity to put his doctrine into practice.

256 | The History of China

Ping-lin), an influential theorist in the Chinese Classics, came to renounce the Three Principles of the People; others deserted to anarchism, leaving anti-Man- chuism as the only common denominator in the league. Organizationally too, the league became divided: the Progressive Society (Gongjinhui), a parallel to the league, was born in Tokyo in 1907; a branch of this new society was soon opened at Wuhan with the ambiguous slogan “Equalization of human right.” The next year, Zhang Binglin tried to revive the Restoration Society.

Constitutional

Movements After 1905

Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) aroused a cry for constitutionalism in China. Unable to resist the intensifying demand, the Qing court decided in September 1906 to adopt a constitution, and in November it reorganized the traditional six boards into 11 ministries in an attempt to modernize the central government. It promised to open consultative provincial assemblies in October 1907 and proclaimed in August 1908 the outline of a constitution and a nine-year period of tutelage before its full implementation.

Three months later the strangely coinciding deaths of Cixi and the emperor were announced, and a boy who ruled as the Xuantong emperor (1908–1911/12) was enthroned under the regency of his father, the second Prince Chun. These deaths, followed by that of Zhang

Zhidong in 1909, almost emptied the Qing court of prestigious members. The consultative provincial assemblies were convened in October 1910 and became the main base of the furious movement for immediate opening of a consultative national assembly, with which the court could not comply.

The gentry and wealthy merchants were the sponsors of constitutionalism; they had been striving to gain the rights held by foreigners. Started first in Hunan, the so-called rights recovery movement spread rapidly and gained noticeable success, reinforced by local officials, students returned from Japan, and the Beijing government. But finally the recovery of the railroad rights ended in a clash between the court and the provincial interests.

The retrieval of the HankouGuangzhou line from the American China Development Company in 1905 tapped a nationwide fever for railway recovery and development. However, difficulty in raising capital delayed railway construction by the Chinese year after year. The Beijing court therefore decided to nationalize some important railways in order to accelerate their construction by means of foreign loans, hoping that the expected railway profits would somehow alleviate the court’s inveterate financial plight. In May 1911 the court nationalized the Hankou-Guangzhou and SichuanHankou lines and signed a loan contract with the four-power banking consortium. This incensed the Sichuan gentry, merchants, and landlords who had invested

Late Qing | 257

in the latter line, and their anti-Beijing remonstrance grew into a province-wide uprising. The court moved some troops into Sichuan from Hubei; some other troops in Hubei mutinied and suddenly occupied the capital city, Wuchang, on October 10. That date became the memorial day of the Chinese Revolution.

The commoners’ standard of living, which had not continued to grow in the 19th century and may have begun to deteriorate, was further dislocated by the mid-century civil wars and foreign commercial and military penetration. Paying for the wars and their indemnities certainly increased the tax burden of the peasantry, but how serious a problem this was has remained an open question among scholars. The Manchu reforms and preparations for constitutionalism added a further fiscal exaction for the populace, which hardly benefited from these urban-oriented developments. Rural distress, resulting from these policies and from natural disasters, was among the causes of local peasant uprisings in the Yangtze River region in 1910 and 1911 and of a major rice riot at Changsha, the capital of Hunan, in 1910. However, popular discontent was limited and not a major factor contributing to the revolution that ended the Qing dynasty and inaugurated the republican era in China.

The Chinese Revolution

(1911–12)

The Chinese Revolution was triggered not by the United League itself but by the

army troops in Hubei who were urged on by the local revolutionary bodies not incorporated in the league. The accidental exposure of a mutinous plot forced a number of junior officers to choose between arrest or revolt in Wuhan. The revolt was initially successful because of the determination of lower-level officers and revolutionary troops and the cowardice of the responsible Manchu and Chinese officials. Within a day the rebels had seized the arsenal and the governorgeneral’s offices and had gained possession of Wuchang. With no nationally known revolutionary leaders on hand, the rebels coerced a colonel, Li Yuanhong, to assume military command, although only as a figurehead. They persuaded the Hubei provincial assembly to proclaim the establishment of the Chinese republic; Tang Hualong, the assembly’s chairman, was elected head of the civil government.

After this initial victory, a number of historical tendencies converged to bring about the downfall of the Qing dynasty. A decade of revolutionary organization and propaganda paid off in a sequence of supportive uprisings in important centres of central and southern China; these occurred in recently formed military academies and in newly created divisions and brigades, in which many cadets and junior officers were revolutionary sympathizers. Secret-society units also were quickly mobilized for local revolts. The antirevolutionary constitutionalist movement also made an important contribution: its leaders had

258 | The History of China

become disillusioned with the imperial government’s unwillingness to speed the process of constitutional government, and a number of them led their respective provincial assemblies to declare their provinces independent of Beijing or to actually join the new republic. Tang Hualong was the first among them. A significant product of the newly emerging nationalism was widespread hostility among Chinese toward the alien dynasty. Many had absorbed the revolutionary propaganda that blamed a weak and vacillating court for the humiliations China had suffered from foreign powers since 1895. Therefore, broad sentiment favoured the end of Manchu rule. Also, as an outcome of two decades of journalizing discussion of “people’s rights,” there was substantial support among the urban educated for a republican form of government. Probably the most-decisive development was the recall of Yuan Shikai (Yüan Shih-k’ai), the architect of the elite Beiyang Army, to government service to suppress the rebellion when its seriousness became apparent.

After the collapse of the Huai Army in the Sino-Japanese War, the Qing government had endeavoured to build up a new Western-style army, among which the elite corps trained by Yuan Shikai, former governor-general of Zhili, had survived the Boxer uprising and emerged as the strongest force in China. But it was in a sense Yuan’s private army and did not easily submit to the Manchu court. Yuan had been retired from officialdom at odds with the regent Prince Chun, but, on

the outbreak of the revolution in 1911, the court had no choice but to recall him from retirement to take command of his new army. Instead of using force, however, he played a double game: on the one hand, he deprived the floundering court of all its power; on the other, he started to negotiate with the revolutionaries. At the peace talks that opened at the end of the year, Yuan’s emissaries and the revolutionary representatives agreed that the abdication of the Qing and the appointment of Yuan to the presidency of the new republic were to be formally decided by a National Assembly that would be formed. However, this was renounced by Yuan, probably because he hoped to be appointed by the retiring Manchu monarch to organize a new government rather than nominated as chief of state by the National Assembly. (This is a formula of the Chinese dynastic revolution called chanrang, which means the peaceful shift in rule from a decadent dynasty to a morevirtuous one.) But events turned against him, and the presidency was given to Sun Yat-sen, who had been appointed provisional president of the republic by the National Assembly. In February 1912 Sun voluntarily resigned his position, and the Qing court proclaimed the decree of abdication, which included a passage—fabricated and inserted by Yuan into this last imperial document— purporting that Yuan was to organize a republican government to negotiate with the revolutionists on unification of northern and southern China. Thus ended the 268-year rule of the Qing dynasty.