- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

The Han Dynasty | 61

new social distinctions were brought into being. Chinese prestige among other peoples varied with the political stability and military strength of the Han house, and the extent of territory that was subject to the jurisdiction of Han officials varied with the success of Han arms. At the same time, the example of the palace, the activities of government, and the growing luxuries of city life gave rise to new standards of cultural and technological achievement.

China’s first imperial dynasty, that of Qin, had lasted barely 15 years before its dissolution in the face of rebellion and civil war. By contrast, Han formed the first long-lasting regime that could successfully claim to be the sole authority entitled to wield administrative power. The Han forms of government, however, were derived in the first instance from the Qin dynasty, and these in turn incorporated a number of features of the government that had been practiced by earlier kingdoms. The Han empire left as a heritage a practical example of imperial government and an ideal of dynastic authority to which its successors aspired. But the Han period has been credited with more success than is its due; it has been represented as a period of 400 years of effective dynastic rule, punctuated by a short period in which a pretender to power usurped authority, and it has been assumed that imperial unity and effective administration advanced steadily with each decade. In fact, there were only a few short periods marked by dynastic strength, stable government, and

intensive administration. Several reigns were characterized by palace intrigue and corrupt influences at court, and on a number of occasions the future of the dynasty was seriously endangered by outbreaks of violence, seizure of political power, or a crisis in the imperial succession.

DyNaSTIC auThORITy aND ThE SuCCESSION Of EMPERORS

Xi (Western) Han

Since at least as early as the Shang dynasty, the Chinese had been accustomed to acknowledging the temporal and spiritual authority of a single leader and its transmission within a family, at first from brother to brother and later from father to son. Some of the early kings had been military commanders, and they may have organized the corporate work of the community, such as the manufacture of bronze tools and vessels. In addition, they acted as religious leaders, appointing scribes or priests to consult the oracles and thus to assist in making major decisions covering communal activities, such as warfare and hunting expeditions. In succeeding centuries the growing sophistication of Chinese culture was accompanied by demands for more-intensive political organization and for more-regular administration; as kings came to delegate tasks to more officials, so was their own authority enhanced and the obedience that they commanded the more

62 | The History of China

widely acknowledged. Under the kingdoms of Zhou, an association was deliberately fostered between the authority of the king and the dispensation exercised over the universe by heaven, with the result that the kings of Zhou and, later, the emperors of Chinese dynasties were regarded as being the sons of heaven.

Prelude to the Han

From 403 BC onward seven kingdoms other than Zhou constituted the ruling authorities in different parts of China, each of which was led by its own king or duke. In theory, the king of Zhou, whose territory was by now greatly reduced, was recognized as possessing superior powers and moral overlordship over the other kingdoms, but practical administration lay in the hands of the seven kings and their professional advisers or in the hands of well-established families. Then in 221 BC, after a long process of expansion and takeover, a radical change occurred in Chinese politics: the kingdom of Qin succeeded in eliminating the power of its six rivals and established a single rule that was acknowledged in their territories. According to later Chinese historians, this success was achieved and the Qin empire was thereafter maintained by oppressive methods and the rigorous enforcement of a harsh penal code, but this view was probably coloured by later political prejudices. Whatever the quality of Qin imperial government, the regime

scarcely survived the death of the first emperor in 210 BC. The choice of his successor was subject to manipulation by statesmen, and local rebellions soon developed into large-scale warfare. Gaozu, whose family had not thus far figured in Chinese history, emerged as the victor of two principal contestants for power. Anxious to avoid the reputation of having replaced one oppressive regime by another, he and his advisers endeavoured to display their own empire—of Han—as a regime whose political principles were in keeping with a Chinese tradition of liberal and beneficent administration. As yet, however, the concept of a single centralized government that could command universal obedience was still subject to trial. In order to exercise and perpetuate its authority, therefore, Gaozu’s government perforce adopted the organs of government, and possibly many of the methods, of its discredited predecessor.

The authority of the Han emperors had been won in the first instance by force of arms, and both Gaozu and his successors relied on the loyal cooperation of military leaders and on officials who organized the work of civil government. In theory and to a large extent in practice, the emperor remained the single source from whom all powers of government were delegated. It was the Han emperors who appointed men to the senior offices of the central government and in whose name the governors of the commanderies (provinces) collected taxes, recruited men for the labour corps and army, and

The Han Dynasty | 63

dispensed justice. And it was the Han emperors who invested some of their kinsmen with powers to rule as kings over certain territories or divested them of such powers in order to consolidate the strength of the central government.

The Imperial Succession

The succession of emperors was hereditary, but it was complicated to a considerable extent by a system of imperial consorts and the implication of their families in politics. Of the large number of women who were housed in the palace as the emperor’s favourites, one was selected for nomination as the empress; while it was theoretically possible for an emperor to appoint any one of his sons heir apparent, this honour, in practice, usually fell on one of the sons of the empress. Changes could be made in the declared succession, however, by deposing one empress and giving the title to another favourite, and sometimes, when an emperor died without having nominated his heir, it was left to the senior statesmen of the day to arrange for a suitable successor. Whether or not an heir had been named, the succession was

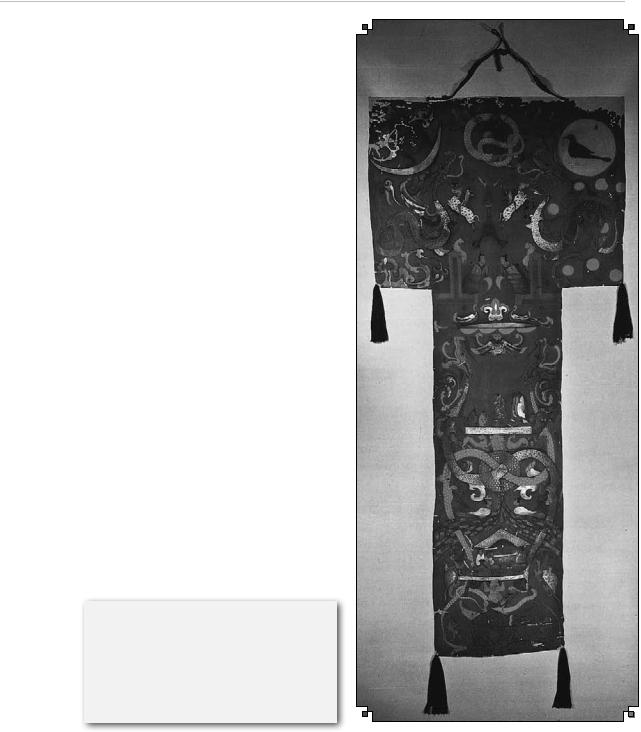

Funerary banner from the tomb of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Mawangdui, Hunan province, ink and colours on silk, c. 168 BC, Western Han dynasty; in the Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha, China.

Wang Lu/ChinaStock Photo Library

64 | The History of China

often open to question, as pressure could be exerted on an emperor over his choice. Sometimes a young or weak emperor was overawed by the expressed will of his mother or by anxiety to please a newly favoured concubine.

Throughout the Xi Han and Dong Han periods, the succession and other important political considerations were affected by the members of the imperial consorts’ families. Often the father or brothers of an empress or concubine were appointed to high office in the central government; alternatively, senior statesmen might be able to curry favour with their emperor or consolidate their position at court by presenting a young female relative for the imperial pleasure. In either situation the succession of emperors might be affected, jealousies would be aroused between the different families concerned, and the actual powers of a newly acceded emperor would be overshadowed by the women in his entourage or their male relatives. Such situations were particularly likely to develop if, as often happened, an emperor was succeeded by an infant son.

The imperial succession was thus frequently bound up with the political machinations of statesmen, particularly as the court grew more sophisticated and statesmen acquired coteries of clients engaged in factional rivalry. On the death of the first emperor, Gaozu (195 BC), the palace came under the domination of his widow. Outliving her son, who had succeeded as emperor under the title of Huidi (reigned 195–188), the empress

dowager Gaohou arranged for two infants to succeed consecutively. During that time (188–180 BC) she issued imperial edicts under her own name and by virtue of her own authority as empress dowager. She set a precedent that was to be followed in later dynastic crises—e.g., when the throne was vacant and no heir had been appointed. In such cases, although statesmen or officials would in fact determine how to proceed, their decisions were implemented in the form of edicts promulgated by the senior surviving empress.

Gaohou appointed a number of members of her own family to highly important positions of state and clearly hoped to substitute her own family for the reigning Liu family. But these plans were frustrated on her death (180) by men whose loyalties remained with the founding emperor and his family. Liu Heng, better known as Wendi, reigned from 180 to 157. He soon came to be regarded (with Gaozu and Wudi) as one of three outstanding emperors of the Xi Han. He was credited with the ideal behaviour of a reigning monarch according to later Confucian doctrine; i.e., he was supposedly ready to yield place to others, hearken to the advice and remonstrances of his statesmen, and eschew personal extravagance. It can be claimed that his reign saw the peaceful consolidation of imperial power, successful experimentation in operating the organs of government, and the steady growth of China’s material resources.

The Han Dynasty | 65

from Wudi to yuandi

The third emperor of the Xi Han to be singled out for special praise by traditional Chinese historians was Wudi (reigned 141–87 BC), whose reign was the longest of the entire Han period. His reputation as a vigorous and brave ruler derives from the long series of campaigns fought chiefly against the Xiongnu

(Hsiung-nu; northern nomads) and in Central Asia, though Wudi never took a personal part in the fighting. The policy of taking the offensive and extending Chinese influence into unknown territory resulted not from the emperor’s initiative but from the stimulus of a few statesmen, whose decisions were opposed vigorously at the time. Thanks to the same statesmen, manpower was more intensively

Wudi

Wudi (b. 156 BC—d. March 29, 87 BC) is the posthumous name given to Liu Che, the sixth emperor of the Xi (Western) Han dynasty. He is noted for vastly increasing the Han’s authority and influence

abroad and for making Confucianism China’s state religion. Under Wudi, China’s armies drove back the nomadic Xiongnu tribes that plagued the northern border, incorporated southern China and northern and central Vietnam into the empire, and reconquered Korea. Their farthest expedition was to Fergana (in modern Uzbekistan). Wudi’s military campaigns strained the state’s reserves; seeking new income, he decreed new taxes and established state monopolies on salt, iron, and wine.

The Wudi emperor is best remembered for his military conquests; hence, his posthumous title, Wudi, meaning “Martial Emperor.” His administrative reforms left an enduring mark on the Chinese state, and his exclusive recognition of Confucianism had a permanent effect on subsequent East Asian history.

66 | The History of China

used and natural resources more heavily exploited during Wudi’s reign, which required more active administration by Han officials. Wudi participated personally in the religious cults of state far more actively than his predecessors and some of his successors. And it was during his reign that the state took new steps to promote scholarship and develop the civil service.

From about 90 BC it became apparent that Han military strength had been overtaxed, leading to a retrenchment in military and economic policies. The last few years of the reign were darkened by a dynastic crisis arising out of jealousies between the empress and heir apparent on the one hand and a rival imperial consort’s family on the other. Intense and violent fighting erupted in Chang’an in 91, and the two families were almost eliminated. A compromise was reached just before Wudi’s death, whereby an infant— known by his posthumous name Zhaodi (reigned 87–74)—who came from neither family was chosen to succeed. The stewardship of the empire was vested in the hands of a regent, Huo Guang, a shrewd and circumspect statesman who already had been in government service for some two decades; even after Huo’s death (68 BC), his family retained a dominating influence in Chinese politics until 64 BC. Zhaodi had been married to a granddaughter of Huo Guang; his successor, who was brought to the throne at the invitation of Huo and other statesmen, proved unfit and was deposed after a reign of 27 days. Huo, however, was able

to contrive a replacement candidate (posthumous name Xuandi) whom he could control or manipulate. Xuandi (reigned 74–49/48), who began to take a personal part in government after Huo Guang’s death, had a predilection for a practical rather than a scholastic approach to matters of state. While his reign was marked by a more rigorous attention to implementing the laws than had heretofore been fashionable, his edicts paid marked attention to the ideals of governing a people in their own interests and distributing bounties where they were most needed. The move away from the aggressive policies of Wudi’s statesmen was even more noticeable during the next reign (Yuandi; 49/48–33).

From Chengdi to Wang Mang

In the reigns of Chengdi (33–7 BC), Aidi (7–1 BC), and Pingdi (1 BC–AD 6) the conduct of state affairs and the atmosphere of the court were subject to the weakness or youth of the emperors, the lack of an heir to succeed Chengdi, and the rivalries between four families of imperial consorts. It was also a time when considerable attention was paid to omens. Changes that were first introduced in the state religious cults in 32 BC were alternately countermanded and reintroduced in the hope of securing material blessings by means of intercession with different spiritual powers. To satisfy the jealousies of a favourite, Chengdi went so far as to murder two sons born to him by other women. Aidi took steps to control the growing