- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

The Early Qing Dynasty | 217

Dorgon

Dorgon (Chinese temple name: Chengzong; b. Nov. 7, 1612—d. Dec. 31, 1650), prince of the Manchu people, was instrumental in founding the Qing (Manchu) dynasty in China. He joined his former enemy Wu Sangui in driving the Chinese rebel Li Zicheng from Beijing, where Li had already unseated the last Ming-dynasty emperor. Though some wanted to put Dorgon on the throne, he saw to it that his nephew Fulin was proclaimed emperor (Dorgon acted as regent); this loyalty and selflessness won him the high regard of future historians.

Sangui, sought Manchu assistance against Li Zicheng. Dorgon, the regent and uncle of Abahai’s infant son (who became the first Qing emperor), defeated Li and took Beijing, where he declared the Manchu dynasty.

It took the Manchu several decades to complete their military conquest of China. In 1673 the conquerors confronted a major rebellion led by three generals (among them Wu Sangui), former Ming adherents who had been given control over large parts of southern and southwestern China. That revolt, stimulated by Manchu attempts to cut back on the autonomous power of these generals, was finally suppressed in 1681. In 1683 the Qing finally eliminated the last stronghold of Ming loyalism on Taiwan.

ThE QINg EMPIRE

After 1683 the Qing rulers turned their attention to consolidating control over their frontiers. Taiwan became part of the empire, and military expeditions

against perceived threats in north and west Asia created the largest empire China has ever known. From the late 17th to the early 18th century, Qing armies destroyed the Oyrat empire based in Dzungaria and incorporated into the empire the region around the Koko Nor (Qinghai Hu, “Blue Lake”) in Central Asia. In order to check Mongol power, a Chinese garrison and a resident official were posted in Lhasa, the centre of the Dge-lugs-pa (Yellow Hat) sect of Buddhism that was influential among Mongols as well as Tibetans. By the mid18th century the land on both sides of the Tien Shan range as far west as Lake Balkhash had been annexed and renamed Xinjiang (“New Dominion”).

Military expansion was matched by the internal migration of Chinese settlers into parts of China that were dominated by aboriginal or non-Han ethnic groups. The evacuation of the south and southeast coast during the 1660s spurred a westward migration of an ethnic minority, the Hakka, who

218 | The History of China

moved from the hills of southwest Fujian, northern Guangdong, and southern Jiangxi. Although the Qing dynasty tried to forbid migration into its homeland, Manchuria, in the 18th and 19th centuries Chinese settlers flowed into the fertile Liao River basin. Government policies encouraged Han movement into the southwest during the early 18th century, while Chinese traders and assimilated Chinese Muslims moved into Xinjiang and the other newly acquired territories. This period was punctuated by ethnic conflict stimulated by the Han Chinese takeover of former aboriginal territories and by fighting between different groups of Han Chinese.

Political Institutions

The Qing had come to power because of their success at winning Chinese over to their side; in the late 17th century they adroitly pursued similar policies to win the adherence of the Chinese literati. Qing emperors learned Chinese, addressed their subjects using Confucian rhetoric, reinstated the civil service examination system and the Confucian curriculum, and patronized scholarly projects, as had their predecessors. They also continued the Ming custom of adopting reign names, so that Xuanye, for example, is known to history as the Kangxi emperor. The Qing rulers initially used only Manchu and bannermen to fill the most-important positions in

the provincial and central governments (half of the powerful governors-general throughout the dynasty were Manchu), but Chinese were able to enter government in greater numbers in the 18th century, and a Manchu-Han dyarchy was in place for the rest of the dynasty.

The early Qing emperors were vigorous and forceful rulers. The first emperor, Fulin (reign name, Shunzhi), was put on the throne when he was a child of six sui (about five years in Western calculations). His reign (1644–61) was dominated by his uncle and regent, Dorgon, until Dorgon died in 1650. Because the Shunzhi emperor had died of smallpox, his successor, the Kangxi emperor, was chosen in part because he had already survived a smallpox attack. The Kangxi emperor (reigned 1661–1722) was one of the most dynamic rulers China has known. During his reign the last phase of the military conquest was completed, and campaigns were pressed against the Mongols to strengthen Qing security on its Central Asian borders. China’s literati were brought into scholarly projects, notably the compilation of the Ming history, under imperial patronage.

The Kangxi emperor’s designated heir, his son Yinreng, was a bitter disappointment, and the succession struggle that followed the latter’s demotion was perhaps the bloodiest in Qing history. Many Chinese historians still question whether the Kangxi emperor’s eventual successor, his son Yinzhen (reign title Yongzheng), was truly the emperor’s

The Early Qing Dynasty | 219

Imperial Chinese throne of the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1735–96), red lacquer carved in dragons and floral scrolls, Qing dynasty; in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; photograph, A.C. Cooper Ltd.

deathbed choice. During the Yongzheng reign (1722–35) the government promoted Chinese settlement of the southwest and tried to integrate non-Han aboriginal groups into Chinese culture; it reformed

the fiscal administration and rectified bureaucratic corruption.

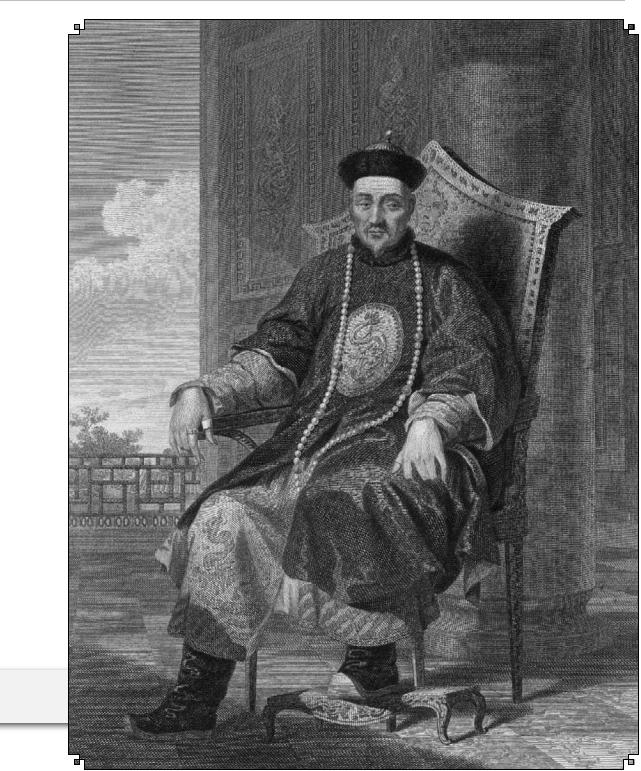

The Qianlong reign (1735–96) marked the culmination of the early Qing. The emperor had inherited an improved

220 | The History of China

bureaucracy and a full treasury from his father and expended enormous sums on the military expeditions known as the Ten Great Victories. He was both noted for his patronage of the arts and notorious for the censorship of antiManchu literary works that was linked with the compilation of the Siku quanshu (“Complete Library of the Four Treasuries”; Eng. trans. under various titles). The closing years of his reign were marred by intensified court factionalism centred on the meteoric rise to political power of an imperial favourite, a young officer named Heshen. Yongyan, who reigned as the Jiaqing emperor (1796–1820), lived most of his life in his father’s shadow. He was plagued by treasury deficits, piracy off the southeast coast, and uprisings among aboriginal groups in the southwest and elsewhere. These problems, together with new pressures resulting from an expansion in opium imports, were passed on to his successor, the Daoguang emperor (reigned 1820–50).

The early Qing emperors succeeded in breaking from the Manchu tradition of collegial rule. The consolidation of imperial power was finally completed in the 1730s, when the Yongzheng emperor destroyed the power base of rival princes. By the early 18th century the Manchu had adopted the Chinese

practice of father-son succession but without the custom of favouring the eldest son. Because the identity of the imperial heir was kept secret until the emperor was on his deathbed, Qing succession struggles were particularly bitter and sometimes bloody.

The Manchu also altered political institutions in the central government. They created an Imperial Household Department to forestall eunuchs from usurping power—a situation that had plagued the Ming ruling house—and they staffed this agency with bond servants. The Imperial Household Department became a power outside the control of the regular bureaucracy. It managed the large estates that had been allocated to bannermen and supervised various government monopolies, the imperial textile and porcelain factories in central China, and the customs bureaus scattered throughout the empire. The size and strength of the Imperial Household Department reflected the accretion of power to the throne that was part of the Qing political process. Similarly, revisions of the system of bureaucratic communication and the creation in 1729 of a new top deci- sion-making body, the Grand Council, permitted the emperor to control more efficiently the ocean of government memorandums and requests.

This 18th-century drawing depicts Qianlong, the fourth emperor of the Qing dynasty. De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images

The Early Qing Dynasty | 221