- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

208 | The History of China

based on consumption. Of all state revenues, more than half seem to have remained in local and provincial granaries and treasuries; of those forwarded to the capital, about half seem normally to have disappeared into the emperor’s personal vaults. Revenues at the disposal of the central government were always relatively small. Prosperity and fiscal caution had resulted in the accumulation of huge surpluses by the 1580s, both in the capital and in many provinces, but thereafter the Sino-Japanese war in Chosŏn, unprecedented extravagances on the part of the long-lived Wanli emperor, and defense against domestic rebels and the Manchu bankrupted both the central government and the imperial household.

Coinage

Copper coins were used throughout the Ming dynasty. Paper money was used for various kinds of payments and grants by the government, but it was always nonconvertible and, consequently, lost value disastrously. It would in fact have been utterly valueless, except that it was prescribed for the payment of certain types of taxes. The exchange of precious metals was forbidden in early Ming times, but gradually bulk silver became common currency, and, after the mid-16th century, government accounts were reckoned primarily in taels (ounces) of silver. By the end of the dynasty, silver coins produced in Mexico, introduced by Spanish sailors based in the Philippines, were becoming common on the south coast.

Because during the last century of the Ming dynasty a genuine money economy emerged and because concurrently some relatively large-scale mercantile and industrial enterprises developed under private as well as state ownership (most notably in the great textile centres of the southeast), some modern-day scholars have considered the Ming age one of “incipient capitalism”; according to this reasoning, European-style mercantilism and industrialization might have evolved had it not been for the Manchu conquest and expanding European imperialism. It would seem clear, however, that private capitalism in Ming times flourished only insofar as it was condoned by the state, and it was never free from the threat of state suppression and confiscation. State control of the economy—and of society in all its aspects, for that matter—remained the dominant characteristic of Chinese life in Ming times, as it had earlier.

Culture

The predominance of state power also marked the intellectual and aesthetic life of Ming China. By requiring use of their interpretations of the Classics in education and in the civil service examinations, the state prescribed the NeoConfucianism of the great Song thinkers Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi as the orthodoxy of Ming times; by patronizing or commandeering craftsmen and artists on a vast scale, it set aesthetic standards for all the minor arts, for architecture, and even for

The Ming Dynasty | 209

Poet on a Mountain Top, ink on paper or ink and light colour on paper, album leaf mounted as a hand scroll, by Shen Zhou, Ming dynasty; in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo., U.S. 38.7 × 60.2 cm. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; purchase Nelson Trust (46–51/2)

painting, and, by sponsoring great scholarly undertakings and honouring practitioners of traditional literary forms, the state established norms in those realms as well. Thus, it has been easy for historians of Chinese culture to categorize the Ming era as an age of bureaucratic monotony and mediocrity, but the stable, affluent Ming society actually proved to be irrepressibly creative and iconoclastic. Drudges by the hundreds and thousands may have been content with producing second-rate imitations or interpretations

of Tang and Song masterpieces in all genres, but independent thinkers, artists, and writers were striking out in many new directions. The final Ming century especially was a time of intellectual and artistic ferment akin to the most seminal ages of the past.

Philosophy and Religion

Daoism and Buddhism by Ming times had declined into ill-organized popular religions, and what organization they had

210 | The History of China

was regulated by the state. State espousal of Zhu Xi thought and state repression of noted early Ming litterateurs, such as the poet Gao Qi and the thinker Fang Xiaoru, made for widespread philosophical conformity during the 15th century. This was perhaps best characterized by the scholar Xue Xuan’s insistence that the Daoist Way had been made so clear by Zhu Xi that nothing remained but to put it into practice. Philosophical problems about human identity and destiny, however, especially in an increasingly autocratic system, rankled in many minds, and new blends of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist elements appeared in a sequence of efforts to find ways of personal self-realization in contemplative, quietistic, and even mystical veins. These culminated in the antirationalist individualism of the famed scholar-statesman Wang Yangming, who denied the external “principles” of Zhu Xi and advocated striving for wisdom through cultivation of the innate knowledge of one’s own mind and attainment of “the unity of knowledge and action.” Wang’s followers carried his doctrines to extremes of self-indulgence, preached to the masses in gatherings resembling religious revivals, and collaborated with so-called “mad” Chan (Zen) Buddhists to spread the notion that Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism are equally valid paths to the supreme goal of individualistic self-fulfillment. Through the 16th century, intense philosophical discussions were fostered, especially in rapidly multiplying private academies (shuyuan).

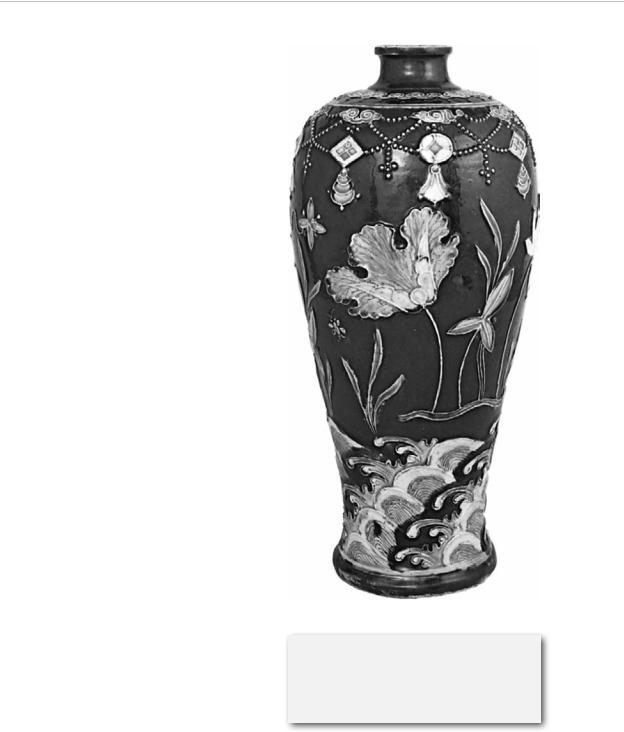

Vase, cloisonné enamel, Ming dynasty, c. 1500; in the British Museum, London. Height 41.5 cm. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum

The Ming Dynasty | 211

Rampant iconoclasm climaxed with Li Zhi, a zealous debunker of traditional Confucian morality, who abandoned a bureaucratic career for Buddhist monkhood of a highly unorthodox type. Excesses of this sort provoked occasional suppressions of private academies, periodic persecutions of heretics, and sophisticated counterarguments from traditionalistic, moralistic groups of scholars, such as those associated with the Donglin Academy near Suzhou, who blamed the late Ming decline of political efficiency and morality on widespread subversion of Zhu Xi orthodoxy. The zealous searching for personal identity was only intensified, however, when the dynasty finally collapsed.

Fine Arts

In the realm of the arts, the Ming period has long been esteemed for the variety and high quality of its state-sponsored craft goods—cloisonné and, particularly, porcelain wares. The sober, delicate monochrome porcelains of the Song dynasty were now superseded by rich, decorative polychrome wares. The best known of these are of blue-on-white decor, which gradually changed from floral and abstract designs to a pictorial emphasis. From that eventually emerged the “willow-pattern” wares that became export goods in great demand in Europe. By late Ming times, perhaps because of the unavailability of the imported Iranian cobalt that was used for the finest

blue-on-white products, more-flamboyant polychrome wares of three and even five colours predominated. Painting—chiefly portraiture—followed traditional patterns under imperial patronage, but independent gentlemen painters became the most esteemed artists of the age, especially four masters of the Wu school (in the Suzhou area): Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. Their work, always of great technical excellence, became less and less academic in style, and out of this tradition, by the late years of the dynasty, emerged a conception of the true painter as a professionally competent but deliberately amateurish artist bent on individualistic self-expres- sion. Notably in landscapes, a highly cultivated and somewhat romantic or mystical simplicity became the approved style, perhaps best exemplified in the work of Dong Qichang.

Literature and Scholarship

As was the case with much of the painting, Ming poetry and belles lettres were deliberately composed “after the fashion of” earlier masters, and groups of writers and critics earnestly argued about the merits of different Tang and Song exemplars. No Ming practitioner of traditional poetry has won special esteem, though Ming literati churned out poetry in prodigious quantities. The historians Song Lian and Wang Shizhen and the philoso- pher-statesman Wang Yangming were among the dynasty’s most noted prose

212 | The History of China

stylists, producing expository writings of exemplary lucidity and straightforwardness. Perhaps the most admired master was Gui Youguang, whose most famous writings are simple essays and anecdotes about everyday life—often rather loose and formless but with a quietly pleasing charm, evoking character and mood with artless-seeming delicacy. The iconoclasm of the final Ming decades was mirrored in a literary movement of total individual freedom, championed notably by Yuan Zhongdao, but writings produced during this period were later denigrated as insincere, coarse, frivolous, and so strange and eccentric as to make impossible demands on the readers.

The late Ming iconoclasm did successfully call attention to popular fiction in colloquial style. In retrospect, this must be reckoned the most significant literary work of the late Yuan and Ming periods, even though it was disdained by the educated elite of the time. The late Yuan–early Ming novels Sanguozhi yanyi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms) and Shuihuzhuan (The Water Margin, also published as All Men Are Brothers) became the universally acclaimed masterpieces of the historical and picaresque genres, respectively. Sequels to each were produced throughout the Ming period. Wu Cheng’en, a 16th-century local official, produced Xiyouji (Journey to the West, also partially translated as Monkey), which became China’s mosttreasured novel of the supernatural. Late in the 16th century an unidentifiable writer produced Jinpingmei (Golden

Lotus), a realistically Rabelaisian account of life and love among the bourgeoisie, which established yet another genre for the novel. By the end of the Ming period, iconoclasts such as Li Zhi and Jin Shengtan, both of whom published editions of Shuihuzhuan, made the then-astonishing assertion that this and other works of popular literature should rank alongside the greatest poetry and literary prose as treasures of China’s cultural heritage. Colloquial short stories also proliferated in Ming times, and collecting anthologies of them became a fad of the last Ming century. The master writer and editor in this realm was Feng Menglong, whose creations and influence dominate the best-known anthology, Jingu qiguan (“Wonders Old and New”), published in Suzhou in 1624.

Operatic drama, which had emerged as a major new art form in Yuan times, was popular throughout the Ming dynasty, and Yuan masterpieces in the tightly disciplined four-act zaju style were regularly performed. Ming contributors to the dramatic literature were most creative in a more-rambling, mul- tiple-act form known as “southern drama” or chuanqi. Members of the imperial clan and respected scholars and officials such as Wang Shizhen and particularly Tang Xianzu wrote for the stage. A new southern opera aria form called kunqu, originating in Suzhou, became particularly popular and provided the repertoire of women singers throughout the country. Sentimental

The Ming Dynasty | 213

romanticism was a notable characteristic of Ming dramas.

Perhaps the most representative of all Ming literary activities, however, are voluminous works of sober scholarship in many realms. Ming literati were avid bibliophiles, both collectors and publishers. They founded many great private libraries, such as the famed Tianyige collection of the Fan family at Ningbo. They also began producing huge anthologies (congshu) of rare or otherwise interesting books and thus preserved many works from extinction. The example was set in this regard by an imperially sponsored classified anthology of all the esteemed writings of the whole Chinese heritage completed in 1407 under the title Yongle dadian (“Great Canon of the Yongle Era”). Its more than 11,000 volumes being too numerous for even the imperial government to consider printing, it was preserved only in manuscript copies; only a fraction of the volumes have survived. Private scholars also produced great illustrated encyclopaedias, including Bencao gangmu (late 16th century; “Index of Native Herbs”), a monumental materia medica listing 1,892 herbal concoctions and their applications; Sancai tuhui (1607–09; “Assembled Pictures of the Three Realms”), a work on subjects such as architecture, tools, costumes, ceremonies, animals, and amusements; Wubeizhi (1621; “Treatise on Military Preparedness”), on weapons, fortifications, defense organization, and war tactics; and Tiangong kaiwu (1637; “Creations of Heaven and Human

Labour”), on industrial technology. Ming scholars also produced numerous valuable geographical treatises and historical studies. Among the creative milestones of Ming scholarship, which pointed the way for the development of modern critical scholarship in early Qing times, were the following: a work by Mei Zu questioning the authenticity of sections of the ancient Shujing (“Classic of History”); a phonological analysis by Chen Di of the ancient Shijing (“Classic of Poetry”); and a dictionary by Mei Yingzuo that for the first time classified Chinese ideograms (characters) under 214 components (radicals) and subclassified them by number of brushstrokes—an arrangement still used by most standard dictionaries.

One of the great all-around literati of Ming times, representative in many ways of the dynamic and wide-ranging activities of the Ming scholar-official at his best, was Yang Shen. Yang won first place in the metropolitan examination of 1511, remonstrated vigorously against the caprices of the Zhengde and Jiajing emperors, and was finally beaten, imprisoned, removed from his post in the Hanlin Academy, and sent into exile as a common soldier in Yunnan. However, throughout his life he produced poetry and belles lettres in huge quantities, as well as a study of bronze and stone inscriptions across history, a dictionary of obsolete characters, suggestions about the phonology of ancient Chinese, and a classification of fishes found in Chinese waters.