- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

26 | The History of China

The stone tools used to clear and prepare the land reveal generally improving technology. There was increasing use of ground and polished edges and of perforation. Regional variations of shape included oval-shaped axes in central and northwest China, squareand trapezoidshaped axes in the east, and axes with stepped shoulders in the southeast. By the Late Neolithic a decrease in the proportion of stone axes to adzes suggests the increasing dominance of permanent agriculture and a reduction in the opening up of new land. The burial in high-status graves of finely polished, perforated stone and jade tools such as axes and adzes with no sign of edge wear indicates the symbolic role such emblems of work had come to play by the 4th and 3rd millennia.

Major Cultures and Sites

There was not one Chinese Neolithic but a mosaic of regional cultures whose scope and significance are still being determined. Their location in the area defined today as China does not necessarily mean that all the Neolithic cultures were Chinese or even protoChinese. Their contributions to the Bronze Age civilization of the Shang, which may be taken as unmistakably Chinese in both cultural as well as geographical terms, need to be assessed in each case. In addition, the presence of a particular ceramic ware does not necessarily define a cultural horizon; transitional phases, both chronological

and geographical, are not discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

Incipient Neolithic

Study of the historical reduction of the size of human teeth suggests that the first human beings to eat cooked food did so in southern China. The sites of Xianrendong in Jiangxi and Zengpiyan in Guangxi have yielded artifacts from the 10th to the 7th millennium BC that include low-fired, cord-marked shards with some incised decoration and mostly chipped stone tools; these pots may have been used for cooking and storage. Pottery and stone tools from shell middens in southern China also suggest Incipient Neolithic occupations. These early southern sites may have been related to the Neolithic Bac Son culture in Vietnam; connections to the subsequent Neolithic cultures of northwestern and northern China have yet to be demonstrated.

6th Millennium BC

Two major cultures can be identified in the northwest: Laoguantai, in eastern and southern Shaanxi and northwestern Henan, and Dadiwan I—a development of Laoguantai culture—in eastern Gansu and western Shaanxi. The pots in both cultures were low-fired, sand-tempered, and mainly red in colour, and bowls with three stubby feet or ring feet were common. The painted bands of this pottery may represent the start of the Painted Pottery culture.

The Beginnings of Chinese History | 27

Silk

Silk is an animal fibre produced by certain insects as building material for cocoons and webs. In commercial use it refers almost entirely to filament from cocoons produced by the caterpillars of several moth species of the genus Bombyx, commonly called silkworms. Silk is a continuous filament around each cocoon. It is freed by softening the cocoon in water and then locating the filament end; the filaments from several cocoons are unwound at the same time, sometimes with a slight twist, to form a single strand. In the process called throwing, several very thin strands are twisted together to make thicker, stronger yarn. Produced since ancient times, the secret of how silk is made was closely guarded for millennia. Along with jade and spices, silk was the primary commodity traded along the Silk Road beginning about 100 BC. Since World War II, nylon and other synthetic fibres have replaced silk in many applications (e.g., parachutes, hosiery, dental floss), but silk remains an important material for clothing and home furnishings.

Silkworms spin cocoons on a silk farm in Zhejiang province. China is the leader in silk production and trade. China Photos/Getty Images

28 | The History of China

In northern China the people of Peiligang (north-central Henan) made less use of cord marking and painted design on their pots than did those at Dadiwan I; the variety of their stone tools, including sawtooth sickles, indicates the importance of agriculture. The Cishan potters (southern Hebei) employed more cord-marked decoration and made a greater variety of forms, including basins, cups, serving stands, and pot supports. The discovery of two pottery models of silkworm chrysalides and 70 shuttlelike objects at a 6th-millennium-BC site at Nanyangzhuang (southern Hebei) suggests the early production of silk, the characteristic Chinese textile.

5th Millennium BC

The lower stratum of the Beishouling culture is represented by finds along the Wei and Jing rivers; bowls, deep-bodied jugs, and three-footed vessels, mainly red in colour, were common. The lower stratum of the related Banpo culture, also in the Wei River drainage area, was characterized by cord-marked red or red-brown ware, especially round and flat-bottomed bowls and pointed-bottomed amphorae. The Banpo inhabitants lived in partially subterranean houses and were supported by a mixed economy of millet agriculture, hunting, and gathering. The importance of fishing is confirmed by designs of stylized fish painted on a few of the bowls and by numerous hooks and net sinkers.

In the east, by the start of the 5th millennium, the Beixin culture in central and

southern Shandong and northern Jiangsu was characterized by fine clay or sandtempered pots decorated with comb markings, incised and impressed designs, and narrow appliquéd bands. Artifacts include many three-legged, deep-bodied tripods, gobletlike serving vessels, bowls, and pot supports. Hougang (lower stratum) remains have been found in southern Hebei and central Henan. The vessels, some finished on a slow wheel, were mainly red-coloured and had been fired at high heat. They include jars, tripods, and round-bottomed, flat-bottomed, and ringfooted bowls. No pointed amphorae have been found, and there were few painted designs. A characteristic red band under the rim of most gray-ware bowls was produced during the firing process.

Archaeologists have generally classified the lower strata of Beishouling, Banpo, and Hougang cultures under the rubric of Painted Pottery (or, after a later site, Yangshao) culture, but two cautions should be noted. First, a distinction may have existed between a more westerly culture in the Wei valley (early Beishouling and early Banpo) that was rooted in the Laoguantai culture and a more easterly one (Beixin and Hougang) that developed from the Peiligang and Cishan cultures. Second, since only 2 to 3 percent of the Banpo pots were painted, the designation Painted Pottery culture seems premature.

In the region of the lower Yangtze River (Chang Jiang), the Hemudu site in northern Zhejiang has yielded caldrons, cups, bowls, and pot supports made of

The Beginnings of Chinese History | 29

porous, charcoal-tempered black pottery. The site is remarkable for its wooden and bone farming tools, the bird designs carved on bone and ivory, the superior carpentry of its pile dwellings (a response to the damp environment), a wooden weaving shuttle, and the earliest lacquerware and rice remains yet reported in the world (c. 5000–4750 BC).

The Qingliangang culture, which succeeded that of Hemudu in Jiangsu, northern Zhejiang, and southern Shandong, was characterized by ringfooted and flat-bottomed pots, gui (wide-mouthed vessels), tripods (common north of the Yangtze), and serving stands (common south of the Yangtze). Early fine-paste redware gave way in the later period to fine-paste gray and black ware. Polished stone artifacts include axes and spades, some perforated, and jade ornaments.

Another descendant of Hemudu culture was that of Majiabang, which had close ties with the Qingliangang culture in southern Jiangsu, northern Zhejiang, and Shanghai. In southeastern China a cord-marked pottery horizon, represented by the site of Fuguodun on the island of Quemoy (Kinmen), existed by at least the early 5th millennium. The suggestion that some of these southeastern cultures belonged to an Austronesian complex remains to be fully explored.

4th and 3rd Millennia BC

A true Painted Pottery culture developed in the northwest, partly from the Wei

valley and Banpo traditions of the 5th millennium. The Miaodigou I horizon, dated from the first half of the 4th millennium, produced burnished bowls and basins of fine red pottery, some 15 percent of which were painted, generally in black, with dots, spirals, and sinuous lines. It was succeeded by a variety of Majiayao cultures (late 4th to early 3rd millennium) in eastern Gansu, eastern Qinghai, and northern Sichuan. About one-third of Majiayao vessels were decorated on the upper two-thirds of the body with a variety of designs in black pigment; multiarmed radial spirals, painted with calligraphic ease, were the most prominent. Related designs involving sawtooth lines, gourd-shaped panels, spirals, and zoomorphic stick figures were painted on pots of the Banshan (mid-3rd millennium) and Machang (last half of 3rd millennium) cultures. Some twothirds of the pots found in the Machang burial area at Liuwan in Qinghai, for example, were painted. In the North China Plain, Dahe culture sites contain a mixture of Miaodigou and eastern, Dawenkou vessel types (see below), indicating that a meeting of two major traditions was taking place in this area in the late 4th millennium.

In the northeast the Hongshan culture (4th millennium and probably earlier) was centred in western Liaoning and eastern Inner Mongolia. It was characterized by small bowls (some with red tops), fine redware serving stands, painted pottery, and microliths. Numerous jade amulets in the form of

30 | The History of China

birds, turtles, and coiled dragons reveal strong affiliations with the other jadeworking cultures of the east coast, such as Liangzhu.

In east China the Liulin and Huating sites in northern Jiangsu (first half of 4th millennium) represent regional cultures that derived in large part from that of Qingliangang. Upper strata also show strong affinities with contemporary Dawenkou sites in southern Shandong, northern Anhui, and northern Jiangsu. Dawenkou culture (mid-5th to at least mid-3rd millennium) is characterized by the emergence of wheel-made pots of various colours, some of them remarkably thin and delicate; vessels with ring feet and tall legs (such as tripods, serving stands, and goblets); carved, perforated, and polished tools; and ornaments in stone, jade, and bone. The people practiced skull deformation and tooth extraction. Mortuary customs involved ledges for displaying grave goods, coffin chambers, and the burial of animal teeth, pig heads, and pig jawbones.

In the middle and lower Yangtze River valley during the 4th and 3rd millennia, the Daxi and Qujialing cultures shared a significant number of traits, including rice production, ring-footed vessels, goblets with sharply angled profiles, ceramic whorls, and black pottery with designs painted in red after firing. Characteristic Qujialing ceramic objects not generally found in Daxi sites include eggshell-thin goblets and bowls painted with black or orange designs, doublewaisted bowls, tall, ring-footed goblets

and serving stands, and many styles of tripods. Admirably executed and painted clay whorls suggest a thriving textile industry. The chronological distribution of ceramic features suggests a transmission from Daxi to Qujialing, but the precise relationship between the two cultures has been much debated.

The Majiabang culture in the Lake Tai basin was succeeded during the 4th millennium by that of Songze. The pots, increasingly wheel-made, were predominantly clay-tempered gray ware. Tripods with a variety of leg shapes, serving stands, gui pitchers with handles, and goblets with petal-shaped feet were characteristic. Ring feet were used, silhouettes became more angular, and triangular and circular perforations were cut to form openwork designs on the shortstemmed serving stands. A variety of jadeornaments,afeatureofQingliangang culture, has been excavated from Songze burial sites.

Sites of the Liangzhu culture (from the last half of the 4th to the last half of the 3rd millennium) have generally been found in the same area. The pots were mainly wheel-made, clay-tempered gray ware with a black skin and were produced by reduction firing; oxidized redware was less prevalent. Some of the serving stand and tripod shapes had evolved from Majiabang prototypes, while other vessel forms included longnecked gui pitchers. The walls of some vessels were black throughout, eggshellthin, and burnished, resembling those found in Late Neolithic sites in Shandong

The Beginnings of Chinese History | 31

(see below). Extravagant numbers of highly worked jade bi disks and cong tubes were placed in certain burials, such as one at Sidun (southern Jiangsu) that contained 57 of them. Liangzhu farmers had developed a characteristic triangular shale plow for cultivating the wet soils of the region. Fragments of woven silk from about 3000 BC have been found at Qianshanyang (northern Zhejiang). Along the southeast coast and on Taiwan, the Dapenkeng cordedware culture emerged during the 4th and 3rd millennia. This culture, with a fuller inventory of pot and tool types than had previously been seen in the area, developed in part from that of Fuguodun but may also have been influenced by cultures to the west and north, including Qingliangang, Liangzhu, and Liulin. The pots were characterized by incised line patterns on neck and rim, low, perforated foot rims, and some painted decoration.

Regional Cultures

of the Late Neolithic

By the 3rd millennium BC, the regional cultures in the areas discussed above showed increased signs of interaction and even convergence. That they are frequently referred to as varieties of the Longshan culture (c. 2500–2000 BC) of east-central Shandong—characterized by its lustrous, eggshell-thin black ware— suggests the degree to which these cultures are thought to have experienced eastern influence. That influence, diverse in origin and of varying intensity, entered

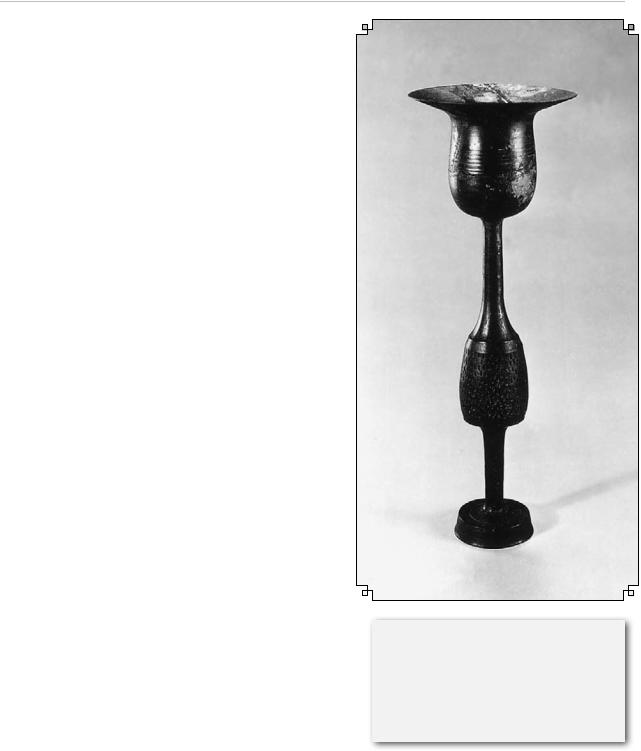

Black pottery stem cup, Neolithic Longshan culture, c. late 3rd millennium BC, from Rizhao, Shandong province, China; in the Shandong Provincial Museum, Jinan. Height 26.5 cm. Wang Lu/ChinaStock Photo Library

32 | The History of China

the North China Plain from sites such as Dadunzi and Dawenkou to the east and also moved up the Han River from the Qujialing area to the south. A variety of eastern features are evident in the ceramic objects of the period, including use of the fast wheel, unpainted surfaces, sharply angled profiles, and eccentric shapes. There was a greater production of gray and black, rather than red, ware; componential construction was emphasized, in which legs, spouts, and handles were appended to the basic form (which might itself have been built sectionally). Greater elevation was achieved by means of ring feet and tall legs. Ceramic objects included three-legged tripods, steamer cooking vessels, gui pouring pitchers, serving stands, fitted lids, cups and goblets, and asymmetrical beihu vases for carrying water that were flattened on one side to lie against a person’s body. In stone and jade objects, eastern influence is evidenced by perforated stone tools and ornaments such as bi disks and cong tubes used in burials. Other burial customs involved ledges to display the goods buried with the deceased and large wooden coffin chambers. In handicrafts an emphasis was placed on precise mensuration in working clay, stone, and wood. Although the first, primitive versions of the eastern ceramic types may have been made on occasion in the North China Plain, in virtually every case these types were elaborated in the east and given more-precise functional definition, greater structural strength, and greater

aesthetic coherence. It was evidently the mixing in the 3rd and 2nd millennia of these eastern elements with the strong and extensive traditions native to the North China Plain—represented by such Late Neolithic sites as Gelawangcun (near Zhengzhou), Wangwan (near Luoyang), Miaodigou (in central and western Henan), and Taosi and Dengxiafeng (in southwest Shanxi)—that stimulated the rise of early Bronze Age culture in the North China Plain and not in the east.

Religious Beliefs and

Social Organization

The inhabitants of Neolithic China were, by the 5th millennium if not earlier, remarkably assiduous in the attention they paid to the disposition and commemoration of their dead. There was a consistency of orientation and posture, with the dead of the northwest given a westerly orientation and those of the east an easterly one. The dead were segregated, frequently in what appear to be kinship groupings (e.g., at Yuanjunmiao, Shaanxi). There were graveside ritual offerings of liquids, pig skulls, and pig jaws (e.g., Banpo and Dawenkou), and the demanding practice of collective secondary burial, in which the bones of up to 70 or 80 corpses were stripped of their flesh and reburied together, was extensively practiced as early as the first half of the 5th millennium (e.g., Yuanjunmiao). Evidence of divination