- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

ChaPTER 8

The yuan, or Mongol, Dynasty

ThE MONgOL

CONQuEST Of ChINa

Genghis Khan rose to supremacy over the Mongol tribes in the steppe in 1206, and within a few years he attempted to conquer northern China. By securing in 1209 the allegiance of the Tangut state of Xi (Western) Xia in what are now Gansu, Ningxia, and parts of Shaanxi and Qinghai, he disposed of a potential enemy and prepared the ground for an attack against the Jin state of the Juchen in northern China. At that time the situation of Jin was precarious. The Juchen were exhausted by a costly war (1206–08) against their hereditary enemies, the Nan (Southern) Song. Discontent among the non-Juchen elements of the Jin population (Chinese and Khitan) had increased, and not a few Chinese and Khitan nobles defected to the Mongol side. Genghis Khan, in his preparation for the campaign against Jin, could therefore rely on foreign advisers who were familiar with the territory and the conditions of the Jin state.

Invasion of the Jin State

The Mongol armies started their attack in 1211, invading from the north in three groups; Genghis Khan led the centre group himself. For several years they pillaged the country;

The Yuan, or Mongol, Dynasty | 169

genghis Khan

Genghis, or Chinggis, Khan (original name Temüjin; b. 1162—d. 1227) was the great Mongolian warrior-ruler of the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Under his leadership, the Mongols consolidated nomadic tribes into a unified Mongolia and fought from China’s Pacific coast to Europe’s Adriatic Sea, creating the basis for one of the greatest continental empires of all time. The leader of a destitute clan, Temüjin fought various rival clans and formed a Mongol confederacy, which in 1206 acknowledged him as Genghis Khan (“Universal Ruler”). By that year the united Mongols were ready to move out beyond the steppe. He adapted his method of warfare, moving from depending solely on cavalry to using sieges, catapults, ladders, and other equipment and techniques suitable for the capture and destruction of cities. In less than 10 years he took over most of Juchencontrolled China; he then destroyed the Muslim Khwārezm-Shah dynasty while his generals raided Iran and Russia. He is infamous for slaughtering the entire populations of cities and destroying fields and irrigation systems but admired for his military brilliance and ability to learn. He died on a military campaign, and the empire was divided among his sons and grandsons.

The Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan on his deathbed, surrounded by his four sons. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

170 | The History of China

finally, in 1214 they concentrated on the central capital of the Jin, Zhongdu (pres- ent-day Beijing). Its fortifications proved difficult to overcome, so the Mongols concluded a peace and withdrew. Shortly afterward the Jin emperor moved to the southern capital at Bianjing (presentday Kaifeng). Genghis Khan considered this a breach of the armistice, and his renewed attack brought large parts of northern China under Mongol control and finally resulted in 1215 in the capture of Zhongdu (renamed Dadu in 1272). The Mongols had had little or no experience in siege craft and warfare in densely populated areas; their strength had been chiefly in cavalry attacks. The assistance of defectors from the Jin state probably contributed to this early Mongol success. In subsequent campaigns the Mongols relied even more on the sophisticated skills and strategies of the increased number of Chinese under their control.

After 1215 the Jin were reduced to a small buffer state between the Mongols in the north and Song China in the south, and their extinction was but a matter of time. The Mongol campaigns against Xi Xia in 1226–27 and the death of Genghis Khan in 1227 brought a brief respite for Jin, but the Mongols resumed their attacks in 1230.

The Song Chinese, seeing a chance to regain some of the territories they had lost to the Juchen in the 12th century, formed an alliance with the Mongols and besieged Bianjing in 1232. Aizong, the emperor of

Jin, left Bianjing in 1233, just before the city fell, and took up his last residence in Cai prefecture (Henan), but that refuge was also doomed. In 1234 the emperor committed suicide, and organized resistance ceased. The southern border of the former Jin state—the Huai River—now became the border of the Mongol dominions in northern China.

Invasion of the Song State

During the next decades an uneasy coexistence prevailed between the Mongols in northern China and the Song state in the south. The Mongols resumed their advance in 1250 under the grand khan Möngke and his brother Kublai Khan— grandsons of Genghis Khan. Their armies outflanked the main Song defenses on the Yangtze River and penetrated deeply into southwestern China, conquered the independent Dai (Tai) state of Nanzhao (in what is now Yunnan), and even reached present-day northern Vietnam. Möngke died in 1259 while leading an army to capture a Song fortress in Sichuan, and Kublai succeeded him. Kublai sent an ambassador, Hao Jing, to the Song court with an offer to establish peaceful coexistence. Hao did not reach the Song capital of Lin’an (now Hangzhou), however, but was interned at the border and regarded as a simple spy. The Song chancellor, Jia Sidao, considered the Song position strong enough to risk this affront against Kublai; he thus ignored the chance for peace offered by

The Yuan, or Mongol, Dynasty | 171

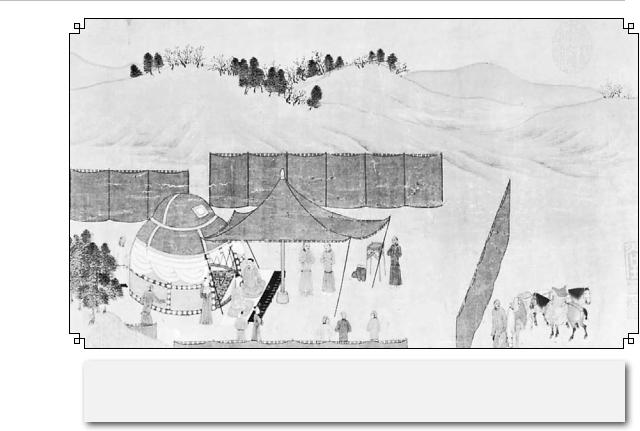

A Mongol encampment, detail from the Cai Wenji scroll, a Chinese hand scroll of the Nan (Southern) Song dynasty. Courtesy of Asia House Gallery, New York

Kublai and instead tried to strengthen the military preparations against a possible Mongol attack. Jia secured military provisions by a land reform that included confiscating land from large owners, but this alienated the greater part of the landlord and official class. The Song generals, whom Jia distrusted, also had grievances, which may explain why a number of them later surrendered to the Mongols without fighting.

From 1267 onward the Mongols, this time assisted by numerous Chinese auxiliary troops and technical specialists, attacked on several fronts. The prefectural

town of Xiangyang (present-day Xianfan) on the Han River was a key fortress, blocking the access to the Yangtze River, and the Mongols besieged it for five years (1268–73). The Chinese commander finally surrendered in 1273, after he had obtained a solemn promise from the Mongols to spare the population, and he took office with his former enemies.

Kublai Khan’s warning to his forces not to engage in indiscriminate slaughter seems to have been heeded to a certain extent. Several prefectures on the Yangtze River surrendered; others were taken after brief fighting. In January 1276,