- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •PREHISTORY

- •EARLY HUMANS

- •NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- •CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENT

- •FOOD PRODUCTION

- •MAJOR CULTURES AND SITES

- •INCIPIENT NEOLITHIC

- •THE FIRST HISTORICAL DYNASTY: THE SHANG

- •THE SHANG DYNASTY

- •THE HISTORY OF THE ZHOU (1046–256 BC)

- •THE ZHOU FEUDAL SYSTEM

- •SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL CHANGES

- •THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM

- •THE RISE OF MONARCHY

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •CULTURAL CHANGE

- •THE QIN EMPIRE (221–207 BC)

- •THE QIN STATE

- •STRUGGLE FOR POWER

- •THE EMPIRE

- •DYNASTIC AUTHORITY AND THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

- •XI (WESTERN) HAN

- •DONG (EASTERN) HAN

- •THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE HAN EMPIRE

- •THE ARMED FORCES

- •THE PRACTICE OF GOVERNMENT

- •RELATIONS WITH OTHER PEOPLES

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE DIVISION OF CHINA

- •DAOISM

- •BUDDHISM

- •THE SUI DYNASTY

- •INTEGRATION OF THE SOUTH

- •EARLY TANG (618–626)

- •ADMINISTRATION OF THE STATE

- •FISCAL AND LEGAL SYSTEM

- •THE PERIOD OF TANG POWER (626–755)

- •RISE OF THE EMPRESS WUHOU

- •PROSPERITY AND PROGRESS

- •MILITARY REORGANIZATION

- •LATE TANG (755–907)

- •PROVINCIAL SEPARATISM

- •CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

- •TRENDS IN THE ARTS

- •SOCIAL CHANGE

- •DECLINE OF THE ARISTOCRACY

- •POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- •GROWTH OF THE ECONOMY

- •THE WUDAI (FIVE DYNASTIES)

- •THE SHIGUO (TEN KINGDOMS)

- •BARBARIAN DYNASTIES

- •THE TANGUT

- •THE KHITAN

- •THE JUCHEN

- •BEI (NORTHERN) SONG (960–1127)

- •UNIFICATION

- •CONSOLIDATION

- •REFORMS

- •DECLINE AND FALL

- •SURVIVAL AND CONSOLIDATION

- •RELATIONS WITH THE JUCHEN

- •THE COURT’S RELATIONS WITH THE BUREAUCRACY

- •THE CHIEF COUNCILLORS

- •THE BUREAUCRATIC STYLE

- •THE CLERICAL STAFF

- •SONG CULTURE

- •INVASION OF THE JIN STATE

- •INVASION OF THE SONG STATE

- •CHINA UNDER THE MONGOLS

- •YUAN CHINA AND THE WEST

- •THE END OF MONGOL RULE

- •POLITICAL HISTORY

- •THE DYNASTY’S FOUNDER

- •THE DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

- •LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- •CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- •LATER INNOVATIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENTS

- •POPULATION

- •AGRICULTURE

- •TAXATION

- •COINAGE

- •CULTURE

- •PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

- •FINE ARTS

- •LITERATURE AND SCHOLARSHIP

- •THE RISE OF THE MANCHU

- •THE QING EMPIRE

- •POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

- •FOREIGN RELATIONS

- •ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

- •QING SOCIETY

- •SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

- •STATE AND SOCIETY

- •TRENDS IN THE EARLY QING

- •POPULAR UPRISING

- •THE TAIPING REBELLION

- •THE NIAN REBELLION

- •MUSLIM REBELLIONS

- •EFFECTS OF THE REBELLIONS

- •INDUSTRIALIZATION FOR “SELF-STRENGTHENING”

- •CHANGES IN OUTLYING AREAS

- •EAST TURKISTAN

- •TIBET AND NEPAL

- •MYANMAR (BURMA)

- •VIETNAM

- •JAPAN AND THE RYUKYU ISLANDS

- •REFORM AND UPHEAVAL

- •THE BOXER REBELLION

- •REFORMIST AND REVOLUTIONIST MOVEMENTS AT THE END OF THE DYNASTY

- •EARLY POWER STRUGGLES

- •CHINA IN WORLD WAR I

- •INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS

- •THE INTERWAR YEARS (1920–37)

- •REACTIONS TO WARLORDS AND FOREIGNERS

- •THE EARLY SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- •PHASE ONE

- •U.S. AID TO CHINA

- •NATIONALIST DETERIORATION

- •COMMUNIST GROWTH

- •EFFORTS TO PREVENT CIVIL WAR

- •CIVIL WAR (1945–49)

- •A RACE FOR TERRITORY

- •THE TIDE BEGINS TO SHIFT

- •COMMUNIST VICTORY

- •RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSOLIDATION, 1949–52

- •THE TRANSITION TO SOCIALISM, 1953–57

- •RURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- •URBAN SOCIALIST CHANGES

- •POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •FOREIGN POLICY

- •NEW DIRECTIONS IN NATIONAL POLICY, 1958–61

- •READJUSTMENT AND REACTION, 1961–65

- •THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, 1966–76

- •ATTACKS ON CULTURAL FIGURES

- •ATTACKS ON PARTY MEMBERS

- •SEIZURE OF POWER

- •SOCIAL CHANGES

- •STRUGGLE FOR THE PREMIERSHIP

- •CHINA AFTER THE DEATH OF MAO

- •DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS

- •INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- •RELATIONS WITH TAIWAN

- •CONCLUSION

- •GLOSSARY

- •FOR FURTHER READING

- •INDEX

142 | The History of China

Khitan took advantage of the changing military balance by threatening another invasion. The idealistic faction, put into power under these critical circumstances in 1043–44, effectively stopped the Xi Xia on the frontier by reinforcing a chain of defense posts and made it pay due respect to the Song as the superior empire (though the Song no longer claimed suzerainty). Meanwhile, peace with the Khitan was again ensured when the Song increased its yearly tribute to them.

The court also instituted administrative reforms, stressing the need for emphasizing statecraft problems in civil service examinations, eliminating patronage appointments for family members and relatives of high officials, and enforcing strict evaluation of administrative performance. It also advocated reducing compulsory labour, land reclamation and irrigation construction, organizing local militias, and thoroughly revising codes and regulations. Though mild in nature, the reforms hurt vested interests. Shrewd opponents undermined the reformers by misleading the emperor into suspecting that they had received too much power and were disrespectful of him personally. With the crises eased, the emperor found one excuse after another to send most reformers away from court. The more conventionally minded officials were returned to power.

Despite a surface of seeming stability, the administrative machinery once again fell victim to creeping deterioration. Some reformers eventually returned to court, beginning in the 1050s, but

their idealism was modified by the political lesson they had learned. Eschewing policy changes and tolerating colleagues of varying opinions, they made appreciable progress by concentrating on the choice of better personnel, proper direction, and careful implementation within the conventional system, but many fundamental problems remained unsolved. Mounting military expenditures did not bring greater effectiveness, and an expanding and more costly bureaucracy could not reverse the trend of declining tax yields. Income no longer covered expenditures. During the brief reign of Yingzong (1063–67), relatively minor disputes and symbolically important issues concerning ceremonial matters embroiled the bureaucracy in mutual and bitter criticism.

Reforms

Shenzong (reigned 1067–85) was a reform emperor. Originally a prince reared outside the palace, familiar with social conditions and devoted to serious studies, he did not come into the line of imperial succession until adoption had put his father on the throne before him. Shenzong responded vigorously (and rather unexpectedly, from the standpoint of many bureaucrats) to the problems troubling the established order, some of which were approaching crisis proportions. Keeping above partisan politics, he made the scholar-poet Wang Anshi his chief councillor and gave him full backing to make sweeping reforms. Known as

The Song Dynasty | 143

the New Laws, or New Policies, these reform measures attempted drastic institutional changes. In sum, they sought administrative effectiveness, fiscal surplus, and military strength. Wang’s famous “Ten Thousand Word Memorial” outlined the philosophy of the reforms. Contrary to conventional Confucian views, it upheld assertive governmental roles, but its ideal remained basically Confucian: economic prosperity would provide the social environment essential to moral well-being.

Never before had the government undertaken so many economic activities. The emperor empowered Wang to institute a top-level office for fiscal planning, which supervised the Finance Commission, previously beyond the jurisdiction of the chief councillor. The government squarely faced the reality of a rapidly spreading money economy by increasing the supply of currency. The state became involved in trading, buying specific products of one area for resale elsewhere (thereby facilitating the exchange of goods), stabilizing prices whenever and wherever necessary, and making a profit itself. This did not displace private trading activities. On the contrary, the government extended loans to small urban and regional traders through state pawnshops—a practice somewhat like modern government banking but unheard-of at the time. Far more important, if not controversial, the government made loans at the interest rate, low for the period, of 20 percent to the whole peasantry during the sowing

season, thus assuring their farming productivity and undercutting their dependency upon usurious loans from the well-to-do. The government also maintained granaries in various cities to ensure adequate supplies on hand in case of emergency need. The burden on wealthy and poor alike was made more equitable by a graduated tax scale based on a reassessment of the size and the productivity of the landholdings. Similarly, compulsory labour was converted to a system of graduated tax payments, which were used to finance a hired-labour service program that at least theoretically controlled underemployment in farming areas. Requisition of various supplies from guilds was also replaced by cash assessments, with which the government was to buy what it needed at a fair price.

Wang’s reforms achieved increased military power as well. To remedy the Song’s military weakness and to reduce the immense cost of a standing professional army, the villages were given the duty of organizing militias, under the old name of baojia, to maintain local order in peacetime and to serve as army reserves in wartime. To reinforce the cavalry, the government procured horses and assigned them to peasant households in northern and northwestern areas. Various weapons were also developed. As a result of these efforts, the empire eventually scored some minor victories along the northwestern border.

The gigantic reform program required an energetic bureaucracy, which Wang attempted to create—with mixed

144 | The History of China

results—by means of a variety of policies: promoting a nationwide state school system; establishing or expanding specialized training in such utilitarian professions as the military, law, and medicine, which were neglected by Confucian education; placing a strong emphasis on supportive interpretations of Classics, some of which Wang himself supplied rather dogmatically; demoting and dismissing dissenting officials (thus creating conflicts in the bureaucracy); and providing strong incentives for better performances by clerical staffs, including merit promotion into bureaucratic ranks.

The magnitude of the reform program was matched only by the bitter opposition to it. Determined criticism came from the groups hurt by the reform measures: large landowners, big merchants, and moneylenders. Noncooperation and sabotage arose among the bulk of the bureaucrats, drawn as they were from the landowning and otherwise wealthy classes. Geographically, the strongest opposition came from the traditionally more conservative northern areas. Ideologically, however, the criticisms did not necessarily coincide with either class background or geographic factors. They were best expressed by many leading scholar-offi- cials, some of whom were northern conservatives while others were brilliant talents from Sichuan. Both the emperor and Wang failed to reckon with the fact that, by its very nature, the entrenched bureaucracy could tolerate no sudden change in the system to which it had

become accustomed. It also reacted against the over concentration of power at the top, which neglected the art of distributing and balancing power among government offices, the overexpansion of governmental power in society, and the tendency to apply policies relatively uniformly in a locally diverse empire.

Without directly attacking the emperor, the critics attacked the reformers for deviating from orthodox Confucianism. It was wrong, the opponents argued, for the state to pursue profits, to assume inordinate power, and to interfere in the normal life of the common people. It was often true as charged that the reforms—and the resulting changes in government—brought about the rise of unscrupulous officials, an increase in high-handed abuses in the name of strict law enforcement, unjustified discrimination against many scholar-officials of long experience, intense factionalism, and resulting wide- spreadmiseriesamongthepopulation—all of which were in contradiction to the claims of the reform objectives. Particularly open to criticism was the rigidity of the reform system, which allowed little regional discretion or desirable adjustment for differing conditions in various parts of the empire.

In essence the reforms augmented growing trends toward both absolutism and bureaucracy. Even in the short run, the cost of the divisive factionalism that the reforms generated had disastrous effects. To be fair, Wang was to blame for his overzealous if not doctrinaire

The Song Dynasty | 145

beliefs, his low tolerance for criticism, and his persistent support of his followers even when their errors were hardly in doubt. Nonetheless, it was Shenzong himself who was ultimately responsible. Determined to have the reform measures implemented, he ignored loud remonstrances, disregarded friendly appeals to have certain measures modified, and continued the reforms after Wang’s retirement.

The traditional historians, by studying documentary evidence alone, overlooked the fact that scholar-officials rarely openly criticized an absolutist emperor, and they generally echoed the critical views of the conservatives in assigning the blame to Wang—a revisionist Confucian in public, a profound Buddhist practitioner in his old age, and a great poet and essayist.

Decline and Fall

Careful balancing of powers in the bureaucracy, through which the rulers acted and from which they received advice and information, was essential to good government in China. The demonstrated success of this principle in early Bei Song so impressed later scholars that they described it as the art of government. It became a lost art under Shenzong, however, in the reform zeal and more so in the subsequent eagerness to do away with the reforms.

The reign of Zhezong (1085–1100) began with a regency under another empress dowager, who recalled the

conservatives to power. An antireform period lasted until 1093, during which time most of the reforms were rescinded or drastically revised. Though men of integrity, the conservatives offered few constructive alternatives. They managed to relax tension and achieve a seeming stability, but this did not prevent old problems from recurring. Some conservatives objected to turning back the clock, especially by swinging to the opposite extreme, but they were silenced. Once the young emperor took control, he undid what the empress dowager had put in place; the pendulum swung once again to a restoration of the reforms, a period that lasted to the end of the Bei Song. In such repeated convulsions, the government could not escape dislocation, and the society became demoralized. Moreover, the restored reform movement was a mere ghost without its original idealism. Enough grounds were found by conservatives out of power to blame the reforms for the fall of the dynasty.

Zhezong’s successor, Huizong (reigned 1100–1125/26), was a great patron of the arts and an excellent artist himself, but such qualities did not make him a good ruler. Indulgent in pleasures and irresponsible in state affairs, he misplaced his trust in favourites. Those in power knew how to manipulate the regulatory system to obtain excessive tax revenues. At first, the complacent emperor granted more support to government schools everywhere; the objection that this move might flood the already crowded

146 | The History of China

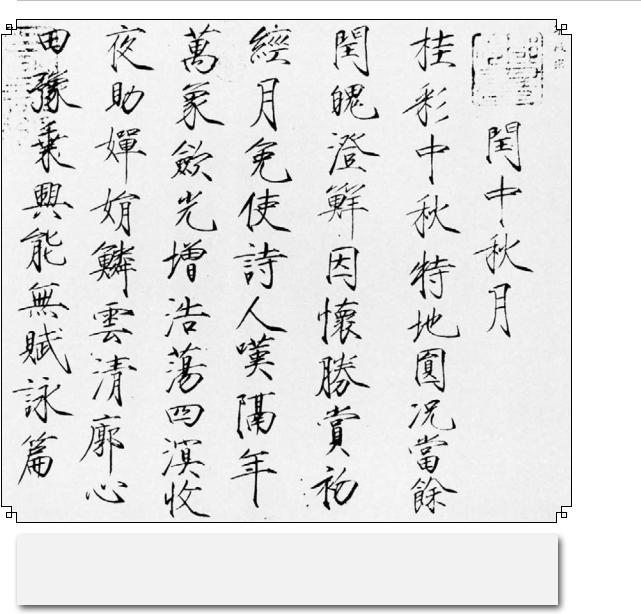

Zhenshu (“regular style”) calligraphy, written by the emperor Huizong (reigned 1100– 1125/26), Bei (Northern) Song dynasty, China; in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

bureaucracy was dismissed, seeing the significant gains it would bring in popular support among scholar-officials. The emperor then commissioned the construction of a costly new imperial garden.

When his extravagant expenditures put the treasury in deficit, he rescinded scholarships in government schools. Support for him among scholar-officials soon vanished.

The Song Dynasty | 147

More serious was carelessness in war and diplomacy. The Song disregarded the treaty and coexistence with the Liao empire, allied itself with the expanding Juchen from Manchuria, and made a concerted attack on the Liao. The Song commander, contrary to long-held prohibition, was a favoured eunuch; under him and other unworthy generals, military expenditures ran high, but army morale was low. The fall of Liao was cause for court celebration, but because the Juchen had done most of the fighting, they accused the Song of not doing its share and denied it certain spoils of the conquest. The Juchen soon turned on the Song. Huizong chose to abdicate at that point, giving himself the title of Daoist “emperor emeritus” and leaving affairs largely in the unprepared hands of his son, Qinzong (reigned 1125/26–1127), while seeking safety and pleasure himself by touring the Yangtze region.

During that period the government became increasingly ineffective. The reform movement had enlarged both the size and duties of the clerical staff. The antireform period brought a cutback but also a confusion that presented manipulative opportunities to some clerks. Supervision was difficult because officials stayed only a few years, whereas clerks remained in office for long periods. Bureaucratic laxity spread quickly to the clerical level. Bribes for appointments went either to them or through their hands. It was they who made cheating possible at examinations, using literary

agents as intermediaries between candidates and themselves.

The Juchen swept across the Huang He plain and found the internally decayed Song an easy prey. During their long siege of Kaifeng (1126), they repeatedly demanded ransoms in gold, silver, jewels, other valuables, and general supplies. The court, whose emergency call for help brought only undermanned reinforcements and untrained volunteers, met the invaders’ demands and ordered the capital residents to follow suit. Finally, an impoverished mob plundered the infamous imperial garden for firewood. The court remained convinced that financial power could buy peace, and the Juchen lifted the siege briefly. But once aware that local resources were exhausted and that the regime, even with the return of the emperor emeritus, no longer had the capability of delivering additional wealth from other parts of the country, the invaders changed their tactics. They captured the two emperors and the entire imperial house, exiled them to Manchuria, and put a tragic end to the Bei Song.

Nan (Southern)

Song (1127–1279)

The Juchen could not extend their conquest south of the Yangtze River. In addition, the Huai River valley, with its winding streams and crisscrossed marshlands, made cavalry operations difficult. Though the invaders penetrated this region and raided several areas below the