- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Abbreviations

- •Contributors

- •1 Normal pregnancy

- •2 Pregnancy complications

- •3 Fetal medicine

- •4 Infectious diseases in pregnancy

- •5 Medical disorders in pregnancy

- •6 Labour and delivery

- •7 Obstetric anaesthesia

- •8 Neonatal resuscitation

- •9 Postnatal care

- •10 Obstetric emergencies

- •11 Perinatal and maternal mortality

- •12 Benign and malignant tumours in pregnancy

- •13 Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders

- •14 Gynaecological anatomy and development

- •15 Normal menstruation and its disorders

- •16 Early pregnancy problems

- •17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

- •18 Subfertility and reproductive medicine

- •19 Sexual assault

- •20 Contraception

- •21 Menopause

- •22 Urogynaecology

- •23 Benign and malignant gynaecological conditions

- •24 Miscellaneous gynaecology

- •Index

Chapter 17 |

549 |

|

|

Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Vaginal discharge 550

Sexually transmitted infections 552 Chlamydia 553

Herpes simplex 554 Gonorrhoea 555 Syphilis 556 Trichomonas 557

Human papillomavirus 558 Bacterial vaginosis 559 Candidiasis (thrush) 560

Pelvic inflammatory disease: overview 561

Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis and treatment 562 Acute pelvic pain 564

Chronic pelvic pain: gynaecological causes 566 Chronic pelvic pain: non-gynaecological causes 567 Chronic pelvic pain: diagnosis and treatment 568

550 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Vaginal discharge

Normal (physiological) discharge occurs in women of reproductive age and varies with the menstrual cycle and hormonal changes.

Causes of increased vaginal discharge

Physiological

•Oestrogen related—puberty, pregnancy, COCP.

•Cycle related—maximal mid-cycle and premenstrual.

•Sexual excitement and intercourse.

Pathological

Infection

•Non-sexually transmitted (BV, candida).

•Sexually transmitted (TV, chlamydia, gonorrhoea).

Non-infective

•Foreign body (retained tampon, condom, or post-partum swab).

•Malignancy (any part of the genital tract).

•Atrophic vaginitis (often blood-stained).

•Cervical ectropion or endocervical polyp.

•Fistulae (urinary or faecal).

•Allergic reactions.

History

•Characteristics of discharge (onset, duration, odour, colour) (Table 17.1).

•Associated symptoms (itching, burning, dysuria, superficial dyspareunia).

•Relationship of discharge to menstrual cycle.

•Precipitating factors (pregnancy, contraceptive pill, sexual excitement).

•Sexual history (risk factors for sexually transmitted infections).

•Medical history (diabetes, immune-compromised).

•Non-infectious causes (foreign body, ectopy, malignancy, dermatological conditions).

•Hygiene practices (douches, bath products, talcum powder).

•Allergies.

Examination

•External genital inspection for vulvitis, obvious discharge, ulcers, or other lesions.

•Speculum: appearance of vagina, cervix, foreign bodies, amount, colour and consistency of discharge.

•Bimanual examination (masses, adnexal tenderness, cervical motion tenderness).

Investigations

•Endocervical or vulvovaginal swabs for gonorrhoea and chlamydia.

•High vaginal swab (Amies transport medium).

•Vaginal pH measurement.

•Saline wet mount and Gram staining (readily available in a genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic, but not usually in gynaecology outpatients.)

•Colposcopy (if abnormal cervical appearance).

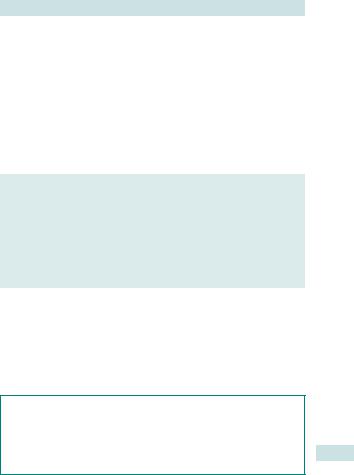

Table 17.1 Typical characteristics of common causes for vaginal discharge

|

Colour |

Consistency |

Odour |

Vulval itching |

Treatment |

Physiological |

Clear/white |

Mucoid |

None |

None |

Reassure |

Candida infection |

White |

Curd-like |

None |

Itching |

Antifungal |

Trichomonal infection |

Green/grey |

Frothy |

Offensive |

Itching |

Metronidazole |

Gonococcal infection |

Greenish |

Watery |

None |

None |

Antibiotics |

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) |

White/grey |

Watery |

Offensive |

None |

Metronidazole |

Malignancy |

Bloody |

Watery |

Offensive |

None |

According to disease |

Foreign body |

Grey or bloody |

Purulent |

Offensive |

None |

Remove object |

Atrophic vaginitis |

Clear/blood-stained |

Watery |

None |

None |

Topical oestrogen |

Cervical ectropion |

Clear |

Watery |

None |

None |

Cryotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clinical Effectiveness Unit (2012). Management of vaginal discharge in non-genitourinary medicine settings. Mhttp://www.bashh.org/documents/4264

DISCHARGE VAGINAL

551

552 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Sexually transmitted infections

•Impact disproportionately on adolescents and young adults.

•Partner notification and treatment vital.

•Best treated at specialist GUM clinic to provide counselling and support, as well as assistance with contact tracing.

•Confidentiality paramount:

•GUM notes are kept separately from hospital notes

•the patient’s GP is not routinely informed of the patient’s attendance.

2 This is a requirement defined by statute in the Venereal Diseases Act of 1917.

2 Assessment of competency should be undertaken if under 16yrs old (Fraser competence).

Risk factors for STIs

•Multiple partners (two or more in the last year).

•Concurrent partners.

•Recent partner change (in past 3mths).

•Non-use of barrier protection.

•STI in partner.

•Other STI.

•Younger age (particularly aged ≤25yrs).

•Involvement in the commercial sex industry.

History

•Symptoms: lumps, bumps, ulcers, rash, itching, IMB or PCB, low abdominal pain, dyspareunia, sudden/distinct change in discharge.

•Past history of STIs/GUM clinic attendance/last HIV –ve test.

•All sexual partners in past 12mths.

•Risk factors for blood-borne viruses:

•patient or partner from area of high HIV prevalence

•IV drug use

•bisexual male partners.

Testing for sexually transmitted infections—incubation period

•Tests should be done at the time of presentation.

•Incubation period before tests for STIs become positive can give false negative after a single episode of sex.

•for bacterial STIs this is 10–14 days

•for HIV and syphilis it may be up to 3mths.

CHLAMYDIA 553

Chlamydia

Epidemiology

•Chlamydia trachomatis: obligate intracellular parasite.

•Commonest bacterial STI in the UK.

•Over 215 000 new cases (127 000 female) diagnosed in the UK in 2010—HPA.

•An important cause of tubal infertility.

Symptoms Dysuria, vaginal discharge, or irregular bleeding (IMB or PCB), but 70% of cases are asymptomatic.

Complications of Chlamydia infection

•Pelvic inflammatory disease (10–40% of infections result in PID).

•Perihepatitis (Fitz–Hugh–Curtis syndrome).

•Reiter’s syndrome (more common in men):

•arthritis

•urethritis

•conjunctivitis.

•Tubal infertility.

•Risk of ectopic pregnancy.

Diagnosis Vulvovaginal (which can be self-taken) or endocervical swab for nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Requires specific medium.

Treatment

•Azithromycin 1g single dose or doxycycline 100mg bd for 7 days— both have similar efficacy of >95%.

•Contact tracing and treatment of partners.

Screening for Chlamydia

During 2010/11 the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) carried out 1.4 million chlamydia tests in England, ensuring 25% coverage of 15–24yr-olds. The Department of Health (DH) estimated that the NCSP may have produced a 20% drop in chlamydia prevalence in under 25s.

Mhttp://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ps/index.html

Implications in pregnancy

Association with preterm rupture of membranes and premature delivery. The risks to the baby are of:

•Neonatal conjunctivitis (30% within the first 2wks).

•Neonatal pneumonia (15% within the first 4mths).

2 Treat pregnant woman with erythromycin 500mg bd for 10–14 days (73–95% effective).

554 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Herpes simplex

Epidemiology

•DNA virus—herpes simplex type 1 (orolabial/genital) and type 2 (genital only).

•Third most common STI in England in 2010.

•Nearly 30 000 primary attacks were diagnosed in England 2010.

Symptoms

Primary HSV infection is usually the most severe and often results in:

•Prodrome (tingling/itching of skin in affected area).

•Flu-like illness +/– inguinal lymphadenopathy.

•Vulvitis and pain (may cause urinary retention).

•Small, characteristic vesicles on the vulva, but can be atypical with fissures, erosions, erythema of skin.

Recurrent attacks are thought to result from reactivation of latent virus in the sacral ganglia, and are normally shorter and less severe. They can be triggered by many factors including:

•Stress.

•Sexual intercourse.

•Menstruation.

Complications of HSV infection (usually of primary infection)

•Meningitis.

•Sacral radiculopathy—causing urinary retention and constipation.

•Transverse myelitis.

•Disseminated infection.

Diagnosis

•Usually from appearance of the typical rash.

•PCR testing of vesicular fluid (most sensitive—gold standard).

•Culture of vesicular fluid.

•Serum antibody tests are of no use for diagnosing primary herpes.

Treatment

•No cure for genital herpes. Symptomatic relief with simple analgesia, saline bathing, and topical anaesthetic.

•Oral aciclovir (200mg 5x day for 5 days or similar), double dose/length if immunosuppressed.

•Topical aciclovir is not beneficial.

•Condoms/abstinence whilst prodromal/symptomatic (unless history of HSV in both partners) may reduce transmission rates.

•Suppressive antiviral treatment—considered if >6 recurrences/year.

Implications in pregnancy

See bHerpes simplex, p. 166.

GONORRHOEA 555

Gonorrhoea

Epidemiology

•Neisseria gonorrhoeae: intracellular Gram –ve diplococcus.

•Fourth most common STI in the UK.

•>18 000 cases were reported in 2010 in the UK.

•>35% of strains are resistant to ciprofloxacin, 70% to tetracyclines.

Symptoms

Usually asymptomatic, often diagnosed when screening on contact tracing. Can present with vaginal discharge, low abdominal pain, IMB or PCB.

Diagnosis

•Endocervical or vulvovaginal swab with NAAT. Urethral, pharyngeal, and rectal swabs if contact with gonorrhoea.

•If diagnosed on NAAT, culture for sensitivity testing should be taken from all sites prior to antibiotic treatment.

Complications of gonococcus infection

•PID (~10% of infections result in PID).

•Bartholin’s or Skene’s abscess.

•Disseminated gonorrhoea may cause:

•fever

•pustular rash

•migratory polyarthralgia

•septic arthritis.

•Tubal infertility.

•Risk of ectopic pregnancy.

Treatment

•Ceftriaxone 500mg IM stat, plus azithromycin 1g PO stat.

•Spectinomycin 2g IM, plus azithromycin 1g PO stat (if severe penicillin allergy).

•Contact tracing and treatment of partners.

•The same antibiotics are recommended for treating gonorrhoea in pregnancy.

Implications in pregnancy

•Gonorrhoea associated with:

•preterm rupture of membranes and premature delivery

•chorioamnionitis.

•The risks to the baby are of ophthalmia neonatarum (40–50%).

Further reading

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Mhttp://www.bashh.org/

556 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Syphilis

Epidemiology

•Treponema pallidum—spirochaete.

•Relatively rare STI in the UK; however, a 12-fold rise 1997–2007.

•Doubling of congenital syphilis from 1999–2007.

•Nearly 3000 cases were diagnosed in 2010 in the UK.

Symptoms

Primary syphilis

•10–90 days postinfection.

•Painless, genital ulcer (chancre)—may pass unnoticed on the cervix.

•Inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Secondary syphilis

•Occurs within the first 2yrs of infection.

•Generalized polymorphic rash affecting palms and soles.

•Generalized lymphadenopathy.

•Genital condyloma lata.

•Anterior uveitis.

Tertiary syphilis

•Presents in up to 40% of people infected for at least 2yrs, but may take 40+yrs to develop.

•Neurosyphilis: tabes dorsalis and dementia.

•Cardiovascular syphilis: commonly affecting the aortic root.

•Gummata: inflammatory plaques or nodules.

Diagnosis

•Specific treponemal enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for screening (IgG + IgM).

•1°lesion smear may show spirochaetes on dark field microscopy.

•Quantitative cardiolipin (non-treponemal) tests, i.e. rapid plasma reagin (RPR)/VDRL are useful in assessing need for and response to treatment.

Treatment

•Depends on penicillin allergy:

•benzathine benzylpenicillin 2.4 MU single dose IM (used in pregnancy)

•doxycycline 100mg bd PO for 14 days (contraindicated in pregnancy),

•erythromycin 500mg qds PO for 14 days (used in pregnancy).

•Treatment courses are longer in tertiary syphilis.

•Contact tracing (potentially over several years).

Implications in pregnancy

•Preterm delivery.

•Stillbirth.

•Congenital syphilis.

•Miscarriage

See Syphilis, bp. 175.

TRICHOMONAS 557

Trichomonas

Epidemiology

•Trichomonas vaginalis—flagellated protozoan.

•Nearly 5000 reported cases in England in 2010.

•Found in vaginal, urethral, and para-urethral glands.

•Cervix may have a ‘strawberry’ appearance from punctate haemorrhages (2%).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic in 10–50%, but may present with:

•Frothy, greenish, offensive smelling vaginal discharge.

•Vulval itching and soreness.

•Dysuria.

Diagnosis

•Direct observation of the organism by a wet smear (normal saline) or acridine orange stained slide from the posterior vaginal fornix (sensitivity 40–70% cases).

•Culture media are available and will diagnose up to 80% cases.

•NAATs have been developed and sensitivities and specificities approaching 100% have been reported.

Complications

There is some evidence that trichomonal infection may enhance HIV transmission.

Treatment

•Metronidazole 2g orally in a single dose.

•Metronidazole 400–500mg bd for 5–7 days.

•Contact tracing and treatment of partners.

Implications in pregnancy

•Trichomonas is associated with:

•preterm delivery

•low birth weight.

•Trichomonas may be acquired perinatally, occurring in 5% of babies born to infected mothers.

558 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Human papillomavirus

Epidemiology

•DNA virus, many subtypes.

•Subtypes 6 and 11 cause genital warts (condylomata acuminata).

•25% of people presenting with warts have other concurrent STIs.

•Commonest viral STI in England.

•>75000 new cases of genital warts diagnosed in England in 2010.

•Subtypes 16 and 18 associated with CIN and cervical neoplasia.

Symptoms Majority asymptomatic. Painless lumps anywhere in the genitoanal area. Perianal warts are common in the absence of anal intercourse.

Diagnosis Usually identified by clinical appearance. Non-wart HPV infection often diagnosed by characteristic appearance on cervical cytology (smear tests) or colposcopy (whitening on topical application of acetic acid).

Complications

HPV 16 and 18 associated with high-grade CIN and cervical neoplasia. Smoking and immunosuppression both affect viral clearance thereby increasing the risk.

Treatment for genital warts

Removal of the visible wart. High rate of recurrence due to the latent virus in the surrounding epithelial cells.

Clinic treatment

•Cryotherapy.

•Trichloroacetic acid.

•Electrosurgery/scissors excision/curettage/laser.

Home treatment (both contraindicated if pregnancy risk)

•Podophyllotoxin cream or solution: this is self-applied and must be used for about 4–6wks.

•Imiquimod cream: this is also a self-applied immune response modifier. It may need to be used for up to 16wks.

Implications in pregnancy

•Genital warts tend to grow rapidly in pregnancy, but usually regress after delivery.

•Very rarely, babies exposed perinatally may develop laryngeal or genital warts.

•Not an indication for CS.

Routine vaccination

•From 2008 the DH has recommended HPV vaccination for all girls aged 12–13.

•Initially the selected vaccine was active against HPV 16 and 18, but in 2012 was changed to include HPV 6 and 11 as well.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS 559

Bacterial vaginosis

Epidemiology

•BV is caused by an overgrowth of mixed anaerobes, including

Gardnerella and Mycoplasma hominis, which replace the usually dominant vaginal lactobacilli.

•Commonest cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of childbearing age.

•Prevalence 5–15% white women, 45–55% black African-American women.

•Not sexually transmitted.

•About 12% of women will experience BV at some point in their lives, but what triggers it remains unclear.

Symptoms

May be asymptomatic, but usually presents with a profuse, whitish grey, offensive smelling vaginal discharge. The characteristic ‘fishy’ smell is due to the presence of amines released by bacterial proteolysis and is often distressing to the woman.

Diagnosis

(Amsel criteria—3 out of 4 required for diagnosis.)

•Homogenous grey-white discharge.

•Increased vaginal pH >5.5.

•Characteristic fishy smell.

•‘Clue cells’ present on microscopy (squamous epithelial cells with bacteria adherent on their walls).

Complications

Increased risk of pelvic infection after gynaecological surgery.

Treatment

May resolve spontaneously and if successfully treated has a high recurrence rate. However, most women prefer it to be treated.

•Metronidazole 400mg orally bd for 5 days; or

•Metronidazole 2g (single dose).

•Clindamycin 2% cream vaginally at night for 7 days.

Lifestyle factors—avoidance of vaginal douching/overwashing which can destroy natural vaginal flora.

Implications in pregnancy

Associated with an increased risk of:

•Mid-trimester miscarriage.

•Preterm rupture of membranes.

•Preterm delivery.

560 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Candidiasis (thrush)

Epidemiology

•Yeast-like fungus (90% Candida albicans, remainder other species, e.g.

C. glabrata).

•About 75% of women will experience at least one episode, and 10–20% are asymptomatic chronic carriers (increasing to 40% during pregnancy).

•Predisposing factors are those that alter the vaginal micro-flora and include:

•immunosuppression

•antibiotics

•pregnancy

•diabetes mellitus

•anaemia.

Symptoms

May be asymptomatic, but usually presents with:

•Vulval itching and soreness.

•Thick, curd-like, white vaginal discharge.

•Dysuria.

•Superficial dyspareunia.

Diagnosis

•Characteristic appearance of:

•vulval and vaginal erythema

•vulval fissuring

•typical white plaques adherent to the vaginal wall.

•Culture from HVS or LVS.

•Microscopic detection of spores and pseudohyphae on wet slides.

Complications

Unlikely to cause any significant complications unless the woman is severely immunocompromised.

Treatment

•As so many women are chronic carriers, candidiasis should only be treated if it is symptomatic.

•Clotrimazole 500mg pessary +/– topical clotrimazole cream; or

•Fluconazole 150mg (single dose)—contraindicated in pregnancy.

Other simple measures may help to decrease recurrent attacks, e.g.:

•Wearing cotton underwear.

•Avoiding chemical irritants, e.g. soap and bath salts.

Implications in pregnancy

•It is very common in pregnancy with no apparent adverse effects.

•Topical imidazoles are not systemically absorbed and are therefore safe at all gestations.

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE: OVERVIEW 561

Pelvic inflammatory disease: overview

Definition PID is infection of the upper genital tract.

Incidence

The exact prevalence is hard to ascertain as many cases may go undetected, but is thought to be in the region of 1–3% of sexually active young women.

Causes

•Most commonly caused by ascending infection from the endocervix, but may also occur from descending infection from organs such as the appendix.

•There are multiple causative organisms:

•25% of cases estimated to be caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

•anaerobes and endogenous agents, either aerobic or facultative, may be responsible for the remainder.

History and examination

•A full gynaecological history including sexual history.

•An abdominal examination to elicit the site and severity of the pain.

•Speculum and vaginal examination to assess for adnexal masses, vaginal discharge, or cervical excitation.

Risk factors for PID

•Age <25.

•Previous STIs.

•New sexual partner/multiple sexual partners.

•Uterine instrumentation such as surgical termination of pregnancy and intrauterine contraceptive devices.

•Post-partum endometritis.

Protective factors

These include the use of barrier contraception, the levonorgestrel (LNG) (Mirena® IUS) and the COCP.

562 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis and treatment

Signs and symptoms

PID may be relatively asymptomatic, the diagnosis only being made retrospectively during investigation of subfertility. Symptoms may include some or all of the following:

•Pelvic pain (may be unilateral), constant or intermittent.

•Deep dyspareunia.

•Vaginal discharge (usually due to concurrent vaginal infection).

•Irregular and/or more painful menses.

•IMB/PCB.

•Fever (unusual in mild/chronic PID).

Signs (at least one of which should be present when making a PID diagnosis) are:

•Cervical motion pain (cervical excitation).

•Adnexal tenderness (commonly bilateral, but may be unilateral).

•Elevated temperature (unusual in mild/chronic infection).

Investigations

•Tests for gonorrhoea and chlamydia.

•WCC and CRP may be elevated.

•USS may be indicated if a tubo-ovarian abscess is suspected.

•Laparoscopy is the gold standard test; however, it is invasive and only used where diagnosis is uncertain.

Complications of PID

•Tubo-ovarian abscess.

•Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome.

•Recurrent PID.

•Ectopic pregnancy.

•Infertility.

Treatment

Early empirical treatment is recommended. Multiple antibiotic regimes are required to cover all potential causative organisms (see b Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis and treatment, p. 563).

•Most patients can be treated in an outpatient setting.

•Review after 72h to ensure adequate response.

•Contact tracing and treatment of partners is essential.

•Inpatient treatment may be required if symptoms are severe, fail to respond, or abscess is suspected.

•If there is USS evidence of a tubo-ovarian abscess, drainage may be required either by ultrasonic guided aspiration or at laparoscopy.

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE: DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT 563

Outpatient management of PID

•IM ceftriaxone 500mg stat plus oral doxycycline 100mg bd 14 days plus oral metronizadole 400mg bd 14 days; or

•Ofloxacin orally 400mg bd 14 days plus metronidazole 400mg bd 14 days (avoid if high risk of gonococcal disease).

1 Doxycycline and metronidazole are commonly used in clinical practice, but there are no clinical trials to support their effectiveness

Inpatient management of PID

•IV ceftriaxone 2g od plus IV doxycycline 100mg bd, followed by oral doxycycline 100mg bd 14 days plus oral metronidazole 400mg bd 14 days; or

•IV clindamycin 900mg tds + IV gentamicin 2mg/kg loading dose followed by 1.5mg/kg tds, followed by either oral clindamycin 450mg qds for a total of 14 days or oral doxycycline 100mg bd + oral metronidazole 400mg bd for a total of 14 days; or

•IV ofloxacin 400mg bd + IV metronidazole 500mg tds for a total of 14 days.

Further reading

RCOG. (2008). Management of acute pelvic inflammatory disease. RCOG guideline 32. M http:// www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/management-acute-pelvic-inflamma- tory-disease-32

564 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Acute pelvic pain

1Acute pelvic pain in a woman of reproductive age with a +ve pregnancy test is an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise.

History

•Pain: site, nature, radiation, aggravating/relieving factors.

•LMP.

•Contraception.

•Recent unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI).

•Risk factors for an ectopic pregnancy (see bEctopic pregnancy: diagnosis, p. 534).

•Vaginal discharge or bleeding.

•Bowel symptoms.

•Urinary symptoms.

•Precipitating factors (physical and psychological).

Examination

•Is she haemodynamically stable? Risk of bleeding from ectopic.

•Abdomen: does she have an acute abdomen? masses?

•Pelvic: are discharge, cervical excitation, adnexal tenderness, masses present?

Investigations

•Urinary/serum hCG.

•MSU.

•Triple swabs (high vaginal, cervical, and endocervical Chlamydia).

•FBC, Group and Save (cross-match if ectopic suspected), CRP.

•Pelvic USS—transvaginal or abdominal as appropriate.

•Abdominal X-ray (+/– contrast), CT, MRI as appropriate.

•Diagnostic laparoscopy.

Treatment

•Resuscitate if necessary.

•Analgesia.

•Specific treatment will depend on cause of pain.

•Avoid unnecessary laparoscopy, especially in a woman with a history of chronic pain.

ACUTE PELVIC PAIN 565

Gynaecological causes of acute pelvic pain

•Early pregnancy complications:

•ectopic pregnancy (see bEctopic pregnancy: diagnosis, p. 534)

•miscarriage (see bMiscarriage: management, p. 532)

•ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (see bOvarian hyperstimulation syndrome, p. 604).

•PID (see bPelvic inflammatory disease: overview p. 561).

•Ovarian cyst accident:

•torsion

•haemorrhage

•rupture.

•Adnexal pathology:

•torsion of fallopian tube/parafimbrial cyst

•salpingo-ovarian abscess.

•Mittelschmerz (German: Mittel = middle, Schmerz = pain).

•Pregnancy complications (see bAbdominal pain in pregnancy: pregnancy related (<24wks), p. 90):

•fibroid degeneration

•ovarian cyst accident

•ligament stretch.

•Primary dysmenorrhoea (see bMenstrual disorders: dysmenorrhea, p. 510).

•Haematometra/haematocolpos.

•Non-gynaecological causes.

•Acute exacerbation of chronic pelvic pain.

Non-gynaecological causes of acute pelvic pain

Gastrointestinal

•Appendicitis.

•Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

•IBD.

•Mesenteric adenitis.

•Diverticulitis.

•Strangulation of a hernia.

Urological

•UTI.

•Renal/bladder calculi.

566 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Chronic pelvic pain: gynaecological causes

Definition Intermittent or constant pelvic pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis of at least 6mths’ duration, not occurring exclusively with menstruation or intercourse and not associated with pregnancy.

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a symptom, not a diagnosis.

Prevalence

•Annual prevalence in women aged 15–73 is 38/1000 (asthma: 37/1000, back pain: 41/1000).

•Many women do not receive a diagnosis even after many years and multiple investigations.

Causes

Endometriosis

See bEndometriosis: overview, p. 582.

Adenomyosis

•Characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium.

•Often occurs after pregnancy, particularly after CS or TOP (breaches the integrity of the endometrial/myometrial junction).

•Initially causes cyclical pelvic pain and menorrhagia, but can worsen until pain is present daily.

Adhesions

Trapped ovary syndrome

After hysterectomy the ovary becomes trapped within dense adhesions at the pelvic side wall.

Pelvic venous congestion

•Dilated pelvic veins, believed to cause a cyclical dragging pain.

•Worst premenstrually and after prolonged periods of standing and walking.

•Dyspareunia is also often present.

Further reading

RCOG. (2012). Chronic pelvic pain: initial management. RCOG Guideline 41. M http://www.rcog. org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/initial-management-chronic-pelvic-pain-green-top-41

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN: NON-GYNAECOLOGICAL CAUSES 567

Chronic pelvic pain: non-gynaecological causes

Gastrointestinal causes

•Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): common, occurring in ~20% of women of reproductive age.

•Constipation: common cause of pelvic pain that is easily treated.

1 Opiate analgesics should not be prescribed for CPP without a laxative.

• Hernia: abdominal or pelvic hernias may cause pain.

Urological causes

Interstitial cystitis (IC)

•Inflammatory disorder causing pain and urinary frequency.

•Diagnosed on cystoscopy.

•Pain is often relieved by voiding.

Urethral syndrome

•Associated with frequency/dysuria in absence of infective cystitis.

•Aetiology is not known, possibly due to a chronic low grade infection of the paraurethral glands (‘female prostatitis’).

Calculi

• May occasionally trigger a chronic pain cycle.

Musculoskeletal causes

Fibromyalgia

•Widespread pain especially in the shoulders, neck, and pelvic girdle.

•Characterized by tender points and a reduced pain threshold.

•Often shows cyclical exacerbations.

Neurological causes

Nerve entrapments

•Trapped in fascia or narrow foramen or in scar tissue after surgery.

•Classically results in pain and/or dysfunction in nerve distribution.

Neuropathic pain

•Results from actual damage to the nerve (surgery, infection, or inflammation).

•Classically described as shooting, stabbing, or burning.

Psychological associations with CPP

•A number of studies have shown that women with CPP have increased number of –ve cognitive and emotional traits, although it is not known whether these are cause or consequence of pain.

•History of abuse (physical, sexual, and psychological) also associated with CPP, but may not be revealed at the first consultation.

568 CHAPTER 17 Genital tract infections and pelvic pain

Chronic pelvic pain: diagnosis and treatment

History

As for acute pelvic pain, but also including:

•A detailed history of the pain, including events surrounding its onset, site, nature, radiation, time course, exacerbating and relieving factors, and any cyclicity.

•A sexual history and future fertility wishes should be explored (it may be possible to discuss abuse at this point).

Examination

•As for acute pelvic pain.

•Speculum may not be appropriate if history of vaginismus or pain sto difficult smear or abuse.

Investigations Be careful not to overinvestigate initially.

Therapeutic trial of GnRH analogues

With clearly cyclical pain, a trial of a GnRH analogue (GnRHa) can be a useful diagnostic tool:

•Women requesting hysterectomy with bilateral salpingooopherectomy can be reassured that it may be a successful treatment if their pain is relieved with a GnRHa.

•If their pain persists on GnRHa treatment, they should be counselled that hysterectomy is unlikely to remove their pain and other causes for it should be explored.

Treatment

Analgesia

•Pre-emptive analgesia may prevent emergency admissions.

•Opiates may be required for severe, acute exacerbations, but if needed regularly, referral to a dedicated pain clinic should be made.

•Neuropathic treatments such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, and

pregabalin can be useful.

Hormonal treatments

The COCP, progestagens, and GnRH analogues can be effective. If pain is improved with a GnRHa then this can be combined safely with low-dose HRT for at least 2yrs.

Complementary therapy

A variety of complementary therapies can produce good results and should be encouraged if the woman suggests them. Support groups can also give reassurance.

Surgery

This has a limited role to play, but hysterectomy can be helpful, as above.