MusculoSkeletal Exam

.pdf

Lister's tubercle

Figure 10.18 Palpation of the dorsal (Lister’s) tubercle of the radius.

Lunate

Figure 10.19 Palpation of the lunate.

Capitate

Figure 10.20 Palpation of the capitate.

245

The Wrist and Hand Chapter 10

MP joint

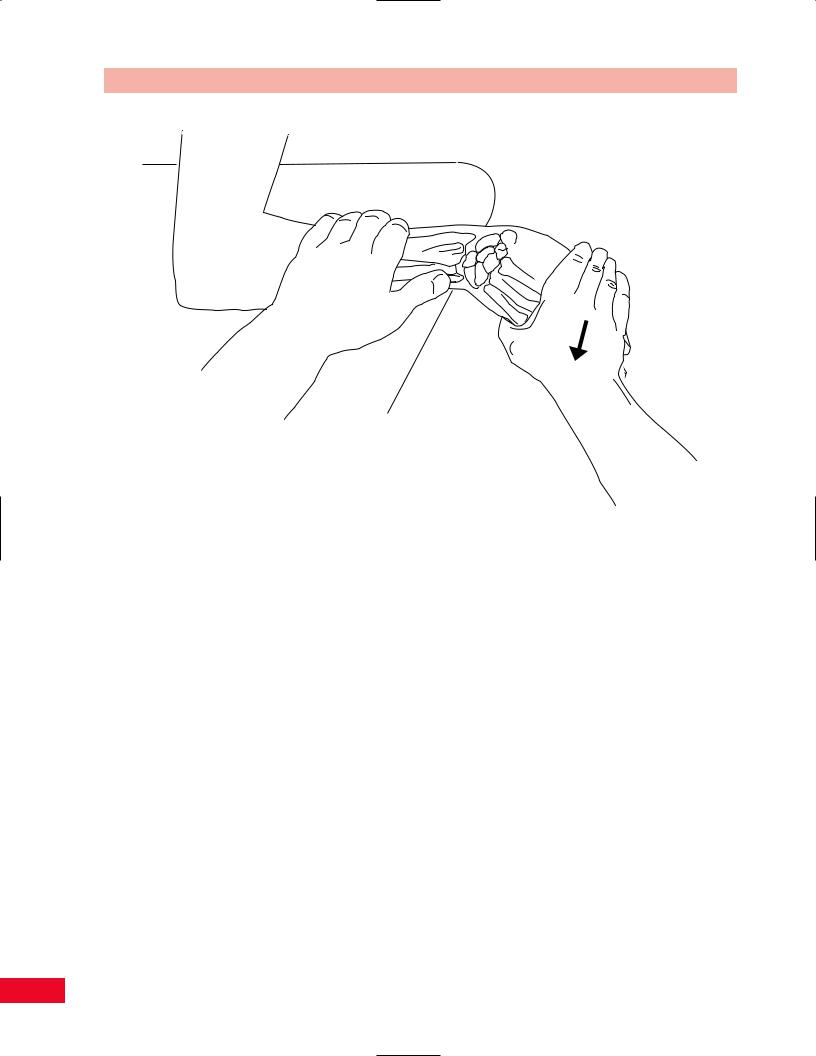

Figure 10.21 Palpation of the metacarpals.

Metacarpals

The metacarpals are more easily palpated from the dorsal aspect of the hand. Pronate the individual’s forearm, rest the palm on your thumb, and palpate the metacarpals using your index and third fingers. Locate the bases of the second through fifth metacarpals just distal to the distal row of carpals. You will notice a flaring of the bones. Trace them distally until you reach the metacarpophalangeal joints (Figure 10.21). You will notice that the fourth and fifth metacarpals are much more mobile than the second and third are because of the less rigid attachment at the carpometacarpal joints. This allows for stability on the lateral aspect of the hand and increased mobility on the medial aspect to allow for power grasp.

Metacarpophalangeal Joints

Continue to follow the metacarpals distally until you reach the metacarpophalangeal joints. The “knuckles” are most clearly visualized on the dorsal surface with the patient’s fingers flexed. In this position, you can more easily visualize and palpate the joint surfaces. The anterior aspect of the metacarpophalangeal joints is deceiving since it appears to be more distal than you would expect. Remember that the joints are located deep to the distal palmar crease (Figure 10.22).

Head of

second metacarpal

Figure 10.22 Palpation of the metacarpophalangeal joints.

246

Chapter 10 The Wrist and Hand

Phalanges and Interphalangeal Joints

The three phalanges of fingers two through five and the two phalanges of the thumb are more easily visualized from the dorsal aspect of the hand. Find the metacarpophalangeal joint and follow the phalanges distally, stopping to palpate the proximal interphalangeal joints and then the distal interphalangeal joints. Note the continuity of the bones and the symmetry of the joints. The interphalangeal joints are common sites for deformities secondary to osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Nails

The finger nails should be smooth and with good coloration. Nail ridges can occur secondary to trauma, avitaminosis, or chronic alcoholism. A direct trauma to the nail can cause bleeding, resulting in a subungual hematoma. Brittle nails with longitudinal ridges can occur secondary to exposure to radiation. Spoonshaped nails can occur due to Plummer–Vinson syndrome which is secondary to iron deficiency anemia. Psoriasis can cause a scaling deformity of the nails. Congenital absence of the thumb nail may be seen in patients with patella–nail syndrome. This is charac-

terized by a small patella, subluxation of the radial head, and a bony projection from the ilium.

Soft-Tissue Structures

Observe the skin over the dorsum of the hand. Notice that it is much looser than the skin over the palm. This allows for greater mobility of the fingers into flexion. Additional skin is noted over the interphalangeal joints and forms transverse ridging. The extensor tendons are clearly visible on the dorsum of the hand since they are not covered by thick fascia, as on the anterior surface. The individual tendons can be traced as they continue to their distal attachments on the bases of the middle phalanges of fingers two through five. The tendons can be made more distinct by resisting finger extension.

Extensor Retinaculum

The extensor retinaculum is a strong fibrous band located on the dorsal aspect of the wrist. It attaches from the anterior border of the radius to the triquetrum and pisiform bones. There are six tunnels deep to the extensor retinaculum that allow for the passage of the extensor tendons into the hand (Figure 10.23).

Extensor rectinaculum

Abductor pollicis

longus

Extensor carpi

ulnaris |

Extensor |

|

pollicis |

||

|

||

Extensor digiti |

brevis |

|

|

||

minimi |

|

|

|

Extensor |

|

|

pollicis |

|

Extensor digititorum tendons |

longus |

|

|

||

|

Extensor indicis |

Figure 10.23 Palpation of the extensor retinaculum.

247

The Wrist and Hand Chapter 10

Extensor pollicis longus

Abductor pollicis brevis

Figure 10.24 Palpation of compartment i.

To enable you to more easily organize the palpation of the deeper soft tissues, the posterior surface of the hand is divided into six areas. The individual compartments are described, from the lateral to the medial aspect.

Compartment I

The most lateral compartment allows the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis to travel to the thumb (Figure 10.24). These muscles comprise the radial border of the anatomical snuff-box (see p. 244 for full description). The tendons can be made more distinct by resisting thumb extension and abduction.

Tenderness in this area may be indicative of de Quervain’s disease, which is a result of stenosing tenosynovitis of the tendon sheath. Differential diagnosis can be done by using Finkelstein’s test, which is described in the special test portion of this chapter (p. 284).

Compartment II

Continuing into the next most medial compartment, which is located lateral to Lister’s tubercle, you will find the extensor carpi radialis longus and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (Figure 10.25). The tendons can be made more distinct by resisting wrist extension and radial deviation.

Extensor carpi radialis brevis

Extensor carpi radialis longus

Figure 10.25 Palpation of compartment ii.

Compartment III

On the medial aspect of Lister’s tubercle you will find the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus as it wraps around the tubercle (Figure 10.26). This tendon creates the medial border of the anatomical snuff-box (see description on p. 244).

248

Lister’s tubercle

Extensor pollicis longus

Figure 10.26 Palpation of compartment iii.

Extensor digitorum

Extensor indicis

Chapter 10 The Wrist and Hand

The tendon travels through a groove on the radius and passes through the extensor retinaculum around the dorsal tubercle of the radius. The tendon has a large degree of angulation, which increases with thumb extension. This tendon can be easily irritated by repetitive use of the thumb. Palpate this tendon for continuity to ensure that it has not been disrupted.

Compartment IV

Compartment IV allows the tendons of the extensor digitorum communis and the extensor indicis to travel to the hand (Figure 10.27). The individual tendons can be traced as they continue to their distal attachments on the bases of the middle and distal phalanges of fingers two through five. It is easiest to locate them in the area between the carpal bones and the metacarpophalangeal joints. The tendons can be made more distinct by resisting finger extension. A rupture or elongation of the terminal portion of the extensor tendon can cause a mallet finger.

Compartment V

As you continue medially, the tendon of the extensor digiti minimi is palpable in a small depression located slightly lateral to the ulna styloid process (Figure 10.28). The tendon can be made more distinct by resisting extension of the fifth finger.

Extensor

Figure 10.27 Palpation of compartment iv. |

Figure 10.28 Palpation of compartment v. |

249

The Wrist and Hand Chapter 10

Extensor carpi ulnaris

Figure 10.29 Palpation of compartment vi.

Compartment VI

The most medial compartment contains the tendon of the extensor carpi ulnaris. The tendon can be palpated in the groove between the head and the styloid process of the ulna as it passes to its distal attachment at the base of the fifth metacarpal (Figure 10.29). It can be made more distinct by resisting wrist extension and ulnar deviation. The tendon can also be palpated by having the patient ulnar deviate the wrist, which increases the tension of the tendon.

Active Movement Testing

The major movements of the wrist joint are flexion, extension, and ulnar and radial deviation. Pronation and supination of the forearm also must be considered. Movements of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints include flexion and extension. Abduction and adduction also occur at the metacarpophalangeal joints. The thumb movements include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and opposition. These should be quick,

functional tests designed to clear the joint. If the motion is pain free at the end of the range, you can add an additional overpressure to “clear” the joint. If the patient experiences pain during any of these movements, you should continue to explore whether the etiology of the pain is secondary to contractile or noncontractile structures by using passive and resistive testing.

Quick testing of the movements of the wrist and hand should be performed simultaneously by both upper extremities. The patient should be sitting with the forearms resting on a treatment table. You should face the patient to observe symmetry of movement.

To examine the wrist–hand complex from proximal to distal, start by asking the patient to supinate and pronate the forearm. A full description of this movement is described in Chapter 9 (pp. 210 –211). Have the patient move the arm so that the wrist is positioned at the end of the table with the forearm pronated. Ask the patient to raise the dorsum of the hand toward the ceiling as far as he or she can, to complete wrist extension. Then ask the patient to allow the hand to bend toward the floor as far as possible, to complete wrist flexion. Instruct the patient to move the arm so that the entire hand is supported on the table in the pronated position. Ask the patient to move the hand to the side, allowing the thumb to approximate the radius to complete the motion of radial deviation. Instruct the patient to return to the neutral position, and then move the hand to the opposite side, with the fifth finger approximating the ulna, to complete ulnar deviation. Note that the range of motion should normally be greater for ulnar deviation since there is no direct contact between the carpals and the ulna because of the meniscus.

To quickly assess the movement of the fingers, instruct the patient to make a tight fist. Observe the quality of the movement and whether all of the fingers are working symmetrically. Full range of motion of finger flexion is accomplished if the patient’s finger tips can contact the proximal palmar crease. Then instruct the patient to release the grasp and straighten out all the fingers, to accomplish finger extension. You should observe that the fingers are either in a straight line (full extension) or slightly hyperextended. Now ask the patient to spread the fingers apart as far as he or she can, starting with the fingers in the extended position and the forearm pronated. Have the patient return the fingers together and they should all be in contact with each other. This accomplishes finger abduction and adduction.

The last movements to be considered are those of the thumb. Have the patient supinate the forearm and

250

then move the thumb diagonally across the palm as far as he or she can. Full thumb flexion should allow the patient to contact the distal palmar crease at the distal aspect of the hypothenar eminence. Then ask the patient to release flexion and move the thumb laterally away from the palm, increasing the dimension of the web space. This is full thumb extension. Next ask the patient to lift the thumb away from the palm toward the ceiling. This motion is thumb abduction. Ask the patient to release the thumb and return to the palm in contact with the second metacarpal. This is thumb adduction. The last thumb movement to be assessed is opposition. Instruct the patient to contact the fingertips starting with the thumb meeting the fifth finger.

Passive Movement Testing

Passive movement testing can be divided into two areas: physiological movements (cardinal plane), which are the same as the active movements, and mobility testing of the accessory (joint play, component) movements. You can determine whether the noncontractile (inert) elements are causative of the patient’s problem by using these tests. These structures (ligaments, joint capsule, fascia, bursa, dura mater, and nerve root) (Cyriax, 1979) are stretched or stressed when the joint is taken to the end of the available range. At the end of each passive physiological movement, you should sense the end feel and determine whether it is normal or pathological. Assess the limitation of movement and see if it fits into a capsular pattern. The capsular pattern of the wrist is equal restriction in all directions (Kaltenborn, 1999; Cyriax, 1979). The capsular pattern of the forearm is equal restriction of pronation and supination, which almost always occurs with significant limitation in the elbow joint

(Kaltenborn, 1999). The capsular patterns for the fingers are as follows: The thumb carpometacarpal joint is limited in abduction followed by extension; finger joints have more limitation of flexion than extension (Cyriax, 1979).

Physiological Movements

You will be assessing the amount of motion available in all directions. Each motion is measured from the zero starting position. For the wrist, the radius and the third metacarpal form a straight line with 0 degrees of

Chapter 10 The Wrist and Hand

flexion and extension. For the fingers, the only resting position described in the literature is for the first carpometacarpal joint. The position is midway between maximal abduction–adduction and flexion–extension (Kaltenborn, 1999).

Supination and Pronation

Supination and pronation are described in Chapter 9 (pp. 210 –211).

Wrist Flexion

The best position for measuring wrist flexion is with the patient sitting, with the arm supported on a treatment table. The forearm should be placed so that the radiocarpal joint is located slightly beyond the edge of the supporting surface to allow for freedom of movement at the wrist joint. The forearm should be pronated, the wrist should be in the zero starting position, and the fingers should be relaxed. Hold the patient’s forearm to stabilize it. Place your hand under the dorsum of the patient’s hand and move the wrist into flexion. The motion may be restricted by tightness in the wrist and finger extensor muscles, the posterior capsule, or the dorsal radiocarpal ligament, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). Normal range of motion is 0–80 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.30).

Wrist Extension

The best position for measuring wrist extension is with the patient sitting, with the arm supported on a treatment table. The forearm should be placed so that the radiocarpal joint is located slightly beyond the edge of the supporting surface to allow for freedom of movement at the wrist joint. The forearm should be pronated, the wrist should be in the zero starting position, and the fingers should be relaxed. Hold the patient’s forearm to stabilize it. Place your hand under the palm of the patient’s hand and move the wrist into extension. The motion may be restricted by tightness in the wrist and finger flexor muscles, the anterior capsule, or the palmar radiocarpal ligament, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). A hard end feel may be present secondary to bony contact between the radius and the proximal carpals. Normal range of motion is 0–70 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.31).

251

The Wrist and Hand Chapter 10

Figure 10.30 Passive movement testing of wrist flexion.

Figure 10.31 Passive movement testing of wrist extension.

252

Chapter 10 The Wrist and Hand

Figure 10.32 Passive movement testing of radial deviation.

Radial Deviation

The best position for measuring wrist radial deviation is with the patient sitting, with the arm supported on a treatment table. The forearm should be placed so that the radiocarpal joint is located slightly beyond the edge of the supporting surface to allow for freedom of movement at the wrist joint. The forearm should be pronated, the wrist should be in the zero starting position, and the fingers should be relaxed. Hold the patient’s forearm to stabilize it and to prevent the patient from substituting with supination and pronation. Place your hand under the palm of the patient’s hand and move the wrist into radial deviation. A hard end feel may be present due to bony contact between the radius and the scaphoid. The motion can be restricted by tension in the ulnar collateral ligament or the ulnar side of the capsule, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). Normal range of motion is 0–20 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.32).

Ulnar Deviation

The best position for measuring wrist ulnar deviation is with the patient sitting, with the arm supported on a

treatment table. The forearm should be placed so that the radiocarpal joint is located slightly beyond the edge of the supporting surface to allow for freedom of movement at the wrist joint. The forearm should be pronated, the wrist should be in the zero starting position, and the fingers should be relaxed. Hold the patient’s forearm to stabilize it and to prevent the patient from substituting with supination and pronation. Place your hand under the palm of the patient’s hand and move the wrist into ulnar deviation. The motion can be restricted by tension in the radial collateral ligament or the radial side of the capsule, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). Normal range of motion is 0–30 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.33).

Fingers

All tests for passive movements of the fingers should be performed with the patient in the sitting position, with the forearm and hand supported on an adjacent treatment table. The examiner should be sitting facing the patient’s hand.

Metacarpophalangeal Joint Flexion

The forearm should be positioned midway between

253

The Wrist and Hand Chapter 10

Figure 10.33 Passive movement testing of ulnar deviation.

pronation and supination with the wrist in the neutral position. The metacarpophalangeal joint should be in the midposition between abduction and adduction. The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints should be comfortably flexed. Avoid the end range of flexion as this will decrease the available range because of tension in the extensor tendons. Place your hand on the metacarpal corresponding to the metacarpophalangeal joint being evaluated. Use your other index finger and thumb to hold the proximal phalanx and move the metacarpophalangeal joint into flexion. The motion can be restricted by tension in the collateral ligaments or the dorsal aspect of the capsule, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel. A hard end feel is possible if contact occurs between the proximal phalanx and the metacarpal (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). Normal range of motion is 0–90 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.34).

Metacarpophalangeal Joint Extension

The forearm should be positioned midway between pronation and supination with the wrist in the neutral position. The metacarpophalangeal joint should be in the midposition between abduction and adduction.

The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints should be comfortably flexed. Place your hand on the metacarpal corresponding to the metacarpophalangeal joint being evaluated. Use your other index finger and thumb to hold the proximal phalanx and move the metacarpophalangeal joint into extension. The motion can be restricted by tension in the volar aspect of the capsule, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel (Kaltenborn, 1999; Magee, 1997). Normal range of motion is 0– 45 degrees (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965) (Figure 10.35).

Metacarpophalangeal Abduction and Adduction

The forearm should be fully pronated with the wrist in the neutral position. The metacarpophalangeal joint should be at 0 degrees of flexion–extension. Use your hand to stabilize the metacarpal to prevent substitution by radial or ulnar deviation. Grasp the finger being examined just proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joint and move it away from the midline for abduction, returning to the midline for adduction. The motion can be restricted by tension in the collateral ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal joints, skin, fascia in the finger web spaces, and the interossei muscles, producing an abrupt and firm (ligamentous) end feel

254