Global corporate finance - Kim

.pdf

482 THE COST OF CAPITAL FOR FOREIGN PROJECTS

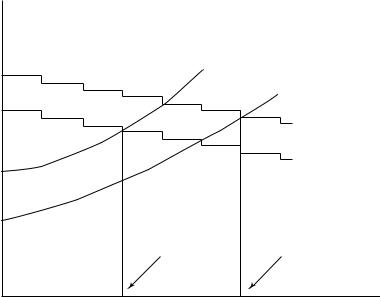

WACC (%)

Weighted average cost of capital

Optimal or target debt range

0 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

Debt ratio (%) |

Figure 19.2 Debt ratio and the cost of capital

19.3 The Marginal Cost of Capital and Investment Decisions

When companies raise funds for new investment projects, they are concerned with the marginal cost of new funds. Companies should always expand their capital budget by raising funds in the same proportion as their optimum capital structure. However, as their capital budget expands in absolute terms, their marginal cost of capital (MCC) will eventually increase. This means that companies can tap only the capital market for some limited amount in the short run before their MCC rises, even though the same optimum capital structure is maintained. The marginal cost of capital is the cost of an additional dollar of new funds.

THE OPTIMUM CAPITAL BUDGET In one analysis, we hold the total amount of capital constant and change only the combination of financing sources. We seek the optimum or target capital structure that yields the lowest cost of capital. In a second analysis, we attempt to determine the size of the capital budget in relation to the levels of the MCC, so that the optimum capital budget can be determined. The optimum capital budget is defined as the amount of investment that maximizes the value of the company. It is obtained at the intersection between the internal rate of return (IRR) and the MCC; at this point total profit is maximized.

A variety of factors affect a company’s cost of capital: its size, access to capital markets, diversification, tax concessions, exchange rate risk, and political risk. The first four factors favor the MNC, whereas the last two factors appear to favor the purely domestic company. For a number

484 THE COST OF CAPITAL FOR FOREIGN PROJECTS

cost of capital and better investment opportunities – give MNCs higher optimum capital budgets than the optimum capital budgets of domestic companies.

Many analysts believe that some countries, such as Germany and Japan, enjoy capital cost advantage mainly due to their high leverage. As the debt ratio increases, the weighted average cost of capital decreases because of the heavier weight of low-cost debt compared to high-cost equity. The low cost of debt is, of course, due to the tax deductibility of interest.

Example 19.3

Assume that there are two countries: X and Y. The cost of debt (10 percent), the cost of equity (15 percent), and the tax rate (50 percent) are the same for these two countries. However, X’s capital structure is 20 percent debt and 80 percent equity, while Y’s capital structure is 50 percent debt and 50 percent equity. Compare the cost of capital in the two countries. The WACC for country X is 13 percent [(0.20 ¥ 0.10)(1 - 0.50) + (0.80 ¥ 0.15)]. If we apply the same costs of debt and equity to the more leveraged country, it would have a WACC of 10 percent [(0.50 ¥ 0.10)(1 - 0.50) + (0.50 ¥ 0.15)]. Hence, the more leveraged country (Y) has a lower cost of capital than the less leveraged country (X).

Companies in Germany and Japan have greater borrowing capacity because their creditors tolerate a high degree of financial leverage. Traditionally, banks in both countries have played a much more important role in corporate financing than capital markets. Companies in both countries could carry a high degree of financial leverage because banks frequently hold bonds and stocks of these companies. Finally, German and Japanese companies have close working relationships with their governments. Hence, it may be in the best interest of the governments to rescue failing companies through direct subsidies and long-term loans, which have enabled these companies to carry a high degree of financial leverage.

19.4 Cultural Values and Capital Structure

Can cultural values be used to predict capital structure across countries? Differences in institutional backgrounds provide only a partial answer to the question of why countries have differences in capital structure (Chui et al. 2002). Researchers from different disciplines have investigated the effects of culture on various business practices, such as the study of management functions, organization design, business performance, compensation practices, cross-border acquisition performance, and managerial attitudes, the perceived importance of job outcomes and job satisfaction, and investor stock-trading decisions. Alternatively, Sekely and Collins (1988) analyzed the relationship between economic variables and international differences in capital structure, but their test results indicated no significant relationship between the two. These two groups of researchers

486 THE COST OF CAPITAL FOR FOREIGN PROJECTS

level of conservatism; and (2) the corporate debt ratio of a country is negatively related to the country’s level of mastery. Conservatism includes values that are important in close-knit harmonious relationships, in which the interests of the individual are not viewed as distinct from those of the group. These values are primarily concerned with security, conformity, and tradition. Mastery accentuates active mastery of the social environment through self-assertion, by placing more emphasis on control and individual success. Such values promote their surroundings and propel them ahead of others.

Their empirical findings support these two hypotheses at both the national and firm levels, which mean that countries with high scores on the cultural dimensions of “conservatism” and “mastery” tend to have low corporate debt ratios. The results are robust even after controlling for the industry effect, the differences in economic performance, legal systems, financial institution development, and other well-known determinants of debt ratios in each country (such as assets tangibility, agency cost, firm size, and profitability).

SUMMARY

The cost of capital, the optimum capital structure, and the optimum capital budget have a major impact on an MNC’s value. The cost of capital is used to evaluate foreign investment projects. The optimum capital structure is a particular debt ratio that simultaneously (a) minimizes the company’s WACC, (b) maximizes the value of the company, and (c) maximizes its share price. The optimum capital budget is the amount of investment that will maximize an MNC’s total profits.

Although the main issues used to analyze the cost of capital in the domestic case provide the foundation for the multinational case, it is necessary to analyze the unique impact of foreignexchange risks, institutional variables, and cultural values. International capital availability, lower risks, and more investment opportunities permit MNCs to lower their cost of capital and to earn more profits.

Questions

1Explain both systematic risk and unsystematic risk within the international context.

2What are the complicated factors in measuring the cost of debt for multinational companies?

3List three choices in deciding a foreign subsidiary’s cost of capital. Which of these three choices is usually used by most multinational companies?

4What factors affect a company’s cost of capital? Why do multinational companies usually enjoy a lower cost of capital than purely domestic companies?

5Some observers believe that American companies can borrow in Japan at relatively low rates of interest. Comment on this argument.

PROBLEMS 487

6In 2002, Chui, Lloyd, and Kwok attempted to find answers to the question of how cultural values can be used to predict capital structure across countries, and why knowing the culture of the country is important for the determination of capital structure. Discuss their findings in some detail.

7Explain why foreign investments for a US company may be less risky than its investment in US assets.

8Why is the optimum capital budget of a multinational company typically higher than that of a purely domestic company?

9Explain why the capital–cost gap across major industrial countries may fall in the future.

Problems

1A foreign project has a beta of 0.50, a risk-free interest rate of 8 percent, and the expected rate of return on the market portfolio is 15 percent. What is the cost of capital for the project?

2A US company borrows Japanese yen for 1 year at 8 percent. During the year, the yen appreciates 10 percent relative to the dollar. The US tax rate is 50 percent. What is the after-tax cost of this debt in US dollar terms?

3The cost of debt (10 percent), the cost of equity (15 percent), and the tax rate (50 percent) are the same for countries A and B. However, A’s capital structure is zero percent debt and 100 percent equity, while B’s capital structure is 50 percent debt and 50 percent equity. Compare the cost of capital in the two countries.

4A company earns $300 per year after taxes and is expected to earn the same amount of profits per year in the future. The company considers three financial plans: A with a debt ratio of 20 percent and a WACC of 15 percent; B with a debt ratio of 40 percent and a WACC of 10 percent; and C with a debt ratio of 80 percent and a WACC of 20 percent. Which debt ratio will maximize the value of the company?

5Assume that a company wishes to sell $6 million worth of bonds and $14 million worth of common stock. The bonds have 13 percent before-tax interest and the stock is expected to pay $1.4 million in dividends. The growth rate of dividends has been 8 percent and is expected to continue at the same rate. Determine the weighted average cost of capital if the tax rate on income is 50 percent.

|

CASE PROBLEM 19 |

489 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

operates in just one country. Finally, an MNC should have higher agency costs than a purely domestic company because the MNC faces higher auditing costs, language differences, sovereign uncertainty, divergent political and economic systems, and varying accounting systems.

To ascertain these four concepts, Burgman (1996) has conducted an extensive empirical study of 251 domestic firms and 236 MNCs. His findings are as follows. First, the mean leverage ratio for the multinational sample is significantly less than that for the domestic sample at the 1 percent level. Second, the operating profits of the multinational sample are more volatile than the domestic sample, although the statistical significance of the difference is weak. Third, domestic companies are significantly more sensitive to exchange rate risk than MNCs at the 5 percent level. Finally, MNCs have significantly higher agency costs than their domestic counterparts at the 1 percent level. Thus, Burgman’s study confirmed only the fourth concept and rejected the other three concepts.

Case Questions

1What is the agency problem? What are agency costs? Why do multinational companies incur higher agency costs than domestic companies?

2Contrary to common expectations, the 1996 study by Burgman has found that multinational companies have lower debt ratios and higher business risks than purely domestic companies. What are possible explanations for this finding?

3What is economic exchange rate risk? Is it easy to hedge this risk? Contrary to common expectations, the 1996 study by Burgman has concluded that multinational companies have lower economic exchange rate risk than domestic companies. What are the possible explanations for this finding?

4Use the website of Bloomberg, www.bloomberg.com/markets, to compare yield rates of government securities for several countries.

Sources: T. A. Burgman, “An Empirical Examination of Multinational Corporate Capital Structure,” Journal of International Business Studies, Third Quarter 1996, pp. 553–70; and J. K. Wald, “How Firm Characteristics Affect Capital Structure: An International Comparison,” The Journal of Financial Research, Summer 1999, pp. 161–87.

CHAPTER 20

Corporate Performance of

Foreign Operations

Opening Case 20: Offshore Workers Increase IBM’s Profits

Until a few years ago, multinational companies (MNCs) used to export only lowly waged jobs, but relentless pressure to cut costs is now compelling many MNCs to export highly paid positions. In one of the largest moves to “offshore” highly paid software jobs, The Wall Street Journal reported on December 14, 2003, that IBM would move 4,730 programmers from the United States to India, China, and elsewhere. Unlike the salaries for low-wage manufacturing jobs, IBM typically paid $75,000 to $100,000 or more a year for the US computer-services work. In contrast, hiring a software engineer with a bachelor’s or even a master’s degree from a top technology university in India may cost $10,000 to $20,000 annually.

Offshore workers account for more than half of IBM’s 315,000 employees. IBM has been a multinational company since the 1920s, with operations in India for 50 years. Until recently, however, most of the software has been designed in the USA and exported to other countries. Apparently, IBM’s effort to export highly paid jobs has recently enabled IBM to be profitable and to gain market share, despite the technology slump in the past few years. No wonder IBM intends to increase the number of its employees in India from 9,000 at the present time to 20,000 by the end of 2005.

The trend looms as one of the most serious long-term threats to US employment and labor. Countries with lower-salaried occupations are no longer siphoning only unskilled or blue-collar jobs from US workers; they now are scooping up skilled work from US companies on a large scale. By the end of 2004, one out of every 10 jobs within US-based computer companies will move to emerging markets, as will one of every 20 technology jobs in other corporations, according to tech-industry researcher

THE GLOBAL CONTROL SYSTEM AND PERFORMANCE EVALUATION |

491 |

|

|

Gartner Inc. The International Data Corporation recently estimated that by 2007, 23 percent of all information technology jobs would be offshore, up from 5 percent in 2003.

Source: “IBM to Export Highly Paid Jobs to India, China,” The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 15, 2003, pp. B1, B3.

Chapter 1 presented hard evidence that companies earn more money as they boost their presence in foreign markets. Furthermore, the first chapter discussed eight principles of global finance that help MNCs perform better than domestic companies. In fact, the entire text of this sixth edition has attempted to cover those financial concepts and techniques that would boost the corporate performance of foreign operations. We conclude this book by discussing how MNCs can use international accounting, taxation, and transfer pricing to improve their overall performance even further.

This chapter consists of three major sections. The first section examines global control systems and performance evaluation of foreign operations. Accurate financial data and an effective control system are especially important in international business, where operations are typically supervised from a distance. The second section considers the significance of national tax systems on international business operations. Perhaps multinational taxation has the most pervasive effect on all aspects of multinational operations. Where to invest, how to finance, and where to remit liquid funds are just a few examples of management actions affected by multinational taxation. The third section covers international transfer pricing. Because transfers between business entities account for approximately one-third of total world trade, the multinational company must try to satisfy a number of objectives. This chapter examines some of these objectives, such as taxes, tariffs, competition, inflation rates, exchange rates, and restrictions on fund transfers.

20.1The Global Control System and Performance Evaluation

In order to achieve the firm’s primary goal of maximizing stockholder wealth, the financial manager performs three major functions: (1) financial planning and control, (2) investment deci- sion-making, and (3) financing decision-making. These financial functions cannot be performed effectively without adequate, timely accounting information. The two fundamental financial statements of any company are the balance sheet and the income statement. The balance sheet measures the assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity of a business at a particular time. The income statement matches expenses to revenues in order to determine the net income or net loss for a period of time. In addition to these two financial statements, a control system is used to relate actual performance to some predetermined goal.

The actual and potential flows of assets across national boundaries complicate the accounting functions of an MNC. The MNC must learn to deal with environmental differences, such as different rates of inflation and changes in exchange rates. If an MNC is to function in a coordinated manner, it must also measure the performance of its foreign affiliates. Equally important, managers of the affiliates must run operations with clearly defined objectives in mind.