Global corporate finance - Kim

.pdf

282 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

ber 2000. In 2001, the Lisbon Exchange decided it would join Euronext. NASDAQ has joint ventures and alliances in Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, Canada, the UK, and Germany. In September 2002, Euronext and the Tokyo Stock Exchange signed an alliance for cooperation and investor protection. In November 2002, the New Zealand Stock Exchange and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange signed an information-sharing agreement. The New York Stock Exchange has recently discussed alliances with markets in Canada, Latin America, Europe, and Asia.

There is a variety of reasons for this consolidation of stock exchanges: the growing speed and power of telecommunication links, big and small investors’ keen interest in stocks from all parts of the world, and the fear of being left behind. Moreover, if national exchanges do not take the initiative, they could be bypassed by new electronic trading systems. These same forces have caused the burgeoning of online trading and have pushed national securities firms to expand their business overseas.

In addition, these same factors have caused another wave of stock markets becoming publicly traded on the different stock exchanges. In 2001, the London Stock Exchange and the Deutsche Bourse went public and are traded on their markets, while the Toronto Stock Exchange and Spain’s four regional stock exchanges went public in 2002. In December 2002, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the world’s second largest futures market, became publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

CROSSLISTING With the rise of cross-border mergers during the 1990s and the early 2000s, there arises a need for companies to crosslist their stocks on different exchanges around the world. By crosslisting its shares on foreign exchanges, an MNC hopes to:

1Allow foreign investors to buy their shares in their home market.

2Increase the share price by taking advantage of the home country’s rules and regulations.

3Provide another market to support a new issuance.

4Establish a presence in that country in the instance that it wishes to conduct business there.

5Increase its visibility to its customers, creditors, suppliers, and the host government.

6Compensate local management and employees in the foreign affiliates.

Companies are obligated to adhere to the securities regulations of all countries where their shares are listed. A decision to crosslist in the USA means that any company, domestic or foreign, must meet the accounting and disclosure requirements of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Rules for listing requirements differ markedly from country to country, but analysts regard US requirements as the most restrictive in the world. Reconciliation of a company’s financial statements to US standards can be a laborious process. Some foreign companies are reluctant to disclose hidden reserves and other pieces of company information. It might not appear too difficult for US companies to crosslist on certain foreign exchanges because their listing requirements are not that restrictive, but certain barriers still exist, such as a foreign country’s specific rules and reporting costs.

STOCK MARKET CONCENTRATION European stock markets have become more integrated since the European Union’s decision to switch their monetary union from the European Currency Unit to the euro, which was launched in 1999. Increasing integration, as reflected in converging price dynamics across markets, results from various structural changes in European stock markets. There is already a large amount of crosslisting and trading among exchanges. Competition among

THE INTERNATIONAL EQUITY MARKET |

283 |

|

|

Percent |

1995 |

2001 |

100 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

40 |

|

|

20 |

|

|

0 |

|

|

Top-31 |

Top-52 |

Top-103 |

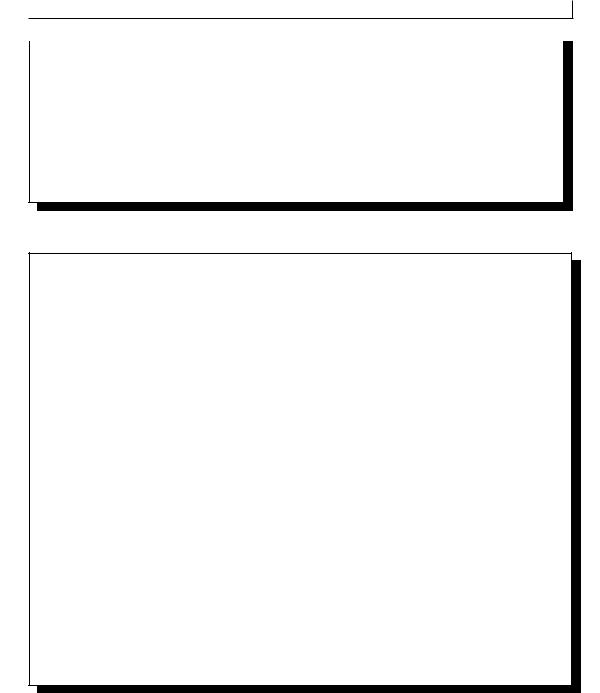

Note: The data used are from the World Federation of Exchanges (market capitalization in US$ millions, end of period) and are subject to price changes between 1995 and 2001.

11995: NYSE, Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), and London Stock Exchange (LSE). 2001: NYSE, NASDAQ, and TSE.

21995: NYSE, TSE, LSE, NASDAQ, and Deutsche Börse. 2001: NYSE, NASDAQ, TSE, LSE, and Euronext.

31995: NYSE, TSE, LSE, NASDAQ, Deutsche Börse, Paris Bourse, Swiss Exchange, Toronto Stock Exchange, Hong Kong Stock Exchange and Clearing, and Amsterdam Exchange. 2001: NYSE, NASDAQ, TSE, LSE, Euronext, Deutsche Börse, Toronto Stock Exchange, Borsa Italiana, Swiss Exchange, and Hong Kong Stock Exchange and Clearing.

Figure 11.3 Major stock exchanges as a share of world stock market capitalization

Source: OECD, Financial Market Trends, Mar. 2003, p. 109.

exchanges for listing and order flow has long characterized European securities markets. In addition, exchanges have become subject to competition for order flow from alternative trading systems. Because there are benefits from achieving large size and attracting liquidity, another important response to competitive pressures has consisted of mergers among exchanges.

The concentration of stock market capitalization is not an “EU phenomenon,” but reflects a worldwide trend toward a single global market for certain instruments. Figure 11.3 shows the share of the three, five, and 10 largest stock exchanges of total world stock market capitalization. The three largest stock markets accounted for 60 percent of the total market capitalization in 1995 and 2001. Furthermore, the share of the five and 10 largest stock markets has increased from 1995 to 2001. These statistics indicate a trend toward concentration of the world stock markets.

11.5.2Privatization

In November 1996, Deutsche Telekom – a government-owned telecommunications company in Germany – raised $13.3 billion through its initial public offering. During the 1990s, the rolling-

284 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

$ billions |

70 |

60 |

50 |

40 |

30 |

20 |

10 |

0 |

1984198819891990199119921993199419951996199719981999

Year

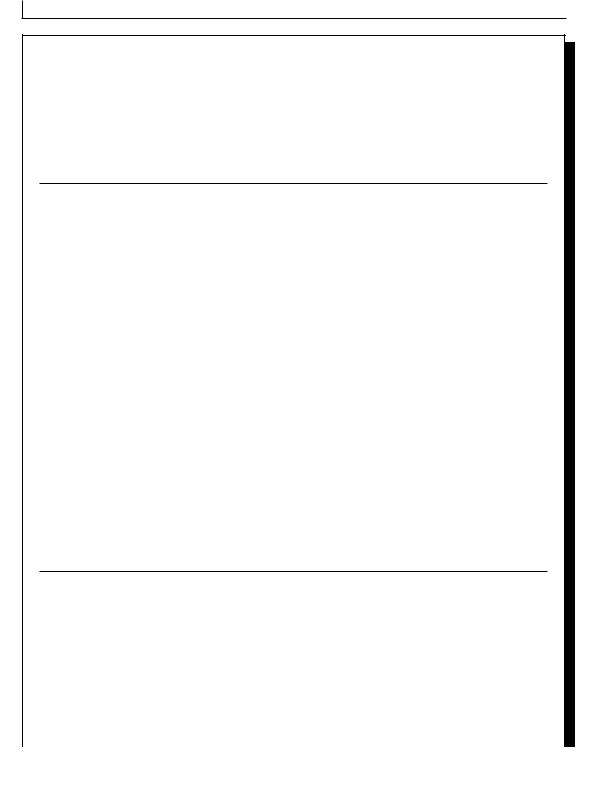

Figure 11.4 Developing countries’ privatization revenues

Source: The World Bank, Global Economic Prospects, 2003, p. 96.

back of state ownership in the economy through privatization gathered considerable pace both in OECD countries and outside the OECD arena. The OECD – the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – is an organization of 29 countries and most of these countries are industrialized.

Privatization is a situation in which government-owned assets are sold to private individuals or groups. In recent years, even many developing countries have been selling government-owned enterprises to private investors. For example, the amount of money raised through privatization by the Indian government increased from $100 million in 1996 to $1,234 million in 1999. In May 2000, the Indian government announced that it would privatize most of the governmentowned enterprises, including Air India, which is the international flag carrier for India. Figure 11.4 shows that the global amount of money raised through privatization by developing countries surged from almost nothing in the early 1980s to $67 billion in 1997, before decreasing to $42 billion in 1999. The World Bank estimates that cumulative privatization revenues worldwide have exceeded $1 trillion by 2000. Privatization could play an important role in the ongoing transformation of emerging capital markets: due to its high profile, privatization may facilitate a switch from investment in bonds to investment in equities.

Why privatize? First, governments try to assist the development of capital markets by increasing market capitalization and liquidity. Second, a closely related motive is to widen share ownership and to create a “shareholder culture” in the population at large. Third, governments use privatization to raise money. Fourth, by replacing public-sector decision-making and control with those of the private sector, privatization is inducing notable changes in the corporate governance structure in important segments of the economy. Finally, privatization enables governments to use their resources more efficiently. By 1990, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) consumed nearly 20 percent of gross domestic investment in developing economies, while producing just more than 10 percent of gross domestic product: “Overall, privatization has dramatically improved the performance of former SOEs” (The World Bank 2003b, p. 96).

How is it done? Privatization takes many forms. First, a government sells state-owned companies directly to a group of ultimate investors. Second, the government divests itself of a company it owns through public offerings of equity in the primary market. The primary market is a market in which the sale of new securities occurs. Third, the government may sell residual

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LONG-TERM CAPITAL FLOWS TO DEVELOPING COUNTRIES |

285 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$ billions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$ billions |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

300 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(a) |

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(b) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Private sector |

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

Inward FDI |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public sector |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Debt |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 |

|

|

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Figure 11.5 (a) Net financial flows to developing countries, 1995–2002; (b) net financial flows to developing countries from the private sector, 1995–2002

Source: The World Bank.

stocks of partly privatized companies in the secondary market. The secondary market is a market for securities that have already been issued and sold. Finally, other privatization methods include leasing, joint ventures, management contracts, and concessions. In 1998, direct sales of government-owned enterprises by developing countries accounted for almost 75 percent of privatization revenues and public offerings contributed to most of the remaining sales.

What are the essential elements for a successful privatization? Any successful privatization involves at least three elements. First, a government needs a political agreement to sell all or part of a company it owns. Second, the company should have the potential to transform itself into a profit-making entity rather than a government-subsidized burden. Third, the government has to find underwriters who will distribute and market the shares domestically and internationally.

11.6 Long-Term Capital Flows to Developing Countries

Figure 11.5(a) shows that long-term capital flows to developing countries have declined since 1998, mainly due to the Asian financial crisis of 1997–8 and the recent slowdown of the global economy. New long-term flows totaled $261 billion in 2002, $83 billion below the peak in 1997. Sharp declines in private capital market flows in recent years – bank loans, bonds, and portfolio equity flows – account for nearly all of this decline. As a result, the share of emerging markets in global capital market financing fell to 3 percent in 2002, compared to 6.4 percent in 1998 and 11 percent in 1997. Figure 11.5(b) shows that even foreign direct investment (FDI), which tends to be more resilient than capital market flows, has slowly but steadily declined since 1999.

11.6.1Rotation from debt to equity

The weakness in the growth of private-sector debt flows is unprecedented in the post-1965 period. In the decade of the 1970s, developing-country debt posted a compound annual growth

286 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

Table 11.6 Developing countries’ debt-to-equity ratios, 1997 and 2002

|

|

|

External debt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Region |

1997 |

2002 |

% GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

East Asia and Pacific |

218% |

134% |

65.0% |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

505% |

293% |

66.8% |

|

Latin American and the Caribbean |

284% |

162% |

67.7% |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

394% |

371% |

42.5% |

|

South Asia |

968% |

613% |

30.5% |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

515% |

303% |

90.6% |

|

All developing countries |

316% |

196% |

61.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: The World Bank, Global Development Finance, Washington,

DC, 2003 and 2004.

rate of 24 percent. The Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s slowed this growth but did not end it. Since the middle of 1998, however, the whole context for development financing has shifted. As borrowers have chosen, or been required by their creditors, to pay down their debts, the external debt of developing countries has fallen in dollar terms. As debt is being repaid to private-sector creditors, net equity flows to developing countries remain significant, mainly though the route of FDI.

The shifting pattern of private flows – debt down, equity up – has had an important implication for the associated stock of debt (see table 11.6). While the stock of developing country external debt outstanding from all sources has fallen since 1998, the stock of equity capital owned and controlled by foreigners has risen over the past decade. Table 11.6 shows that the drop in the external debt-to-equity ratio, from 316 percent in 1997 to 196 percent in 2002, has been spread across all regions of the developing world. The World Bank highlighted three aspects of the shift in its 2004 Global Development Finance. First, the shift is partly driven by investor preferences. Debt investors have become more wary of holding debt claims on developing countries, while MNCs have increasingly come to believe that the developing world offers significant growth opportunities. Second, the shift is privately driven by the preferences of developing country policy-makers. To protect against debt crises, such as the Asian financial crisis of 1997–8, countries have strengthened their precautionary reserve holdings and shifted their liabilities to more stable form of investment, especially FDI. Finally, on balance, the shift is a positive development. This rotation from debt to equity is best seen as a constructive development, because it puts development finance on a stable footing.

SUMMARY

The international financial market consists of the Eurodollar market, the international bond market, and the international equity market. Eurodollars are dollar-denominated deposits in banks all over the world except the USA. The Eurodollar market is the truly international money market, undisturbed by the rules and restrictions of any national authority. Eurodollars have become a major

QUESTIONS 287

source of short-term loans for MNCs to finance their working capital needs and foreign trade. With the growth in availability of Eurodollars, Eurobanks have begun to extend medium-term Eurodollar loans for MNCs to finance their medium-term needs.

Although the international bond and equity markets are of a more recent vintage, they parallel the importance of multinational financial management and mainly facilitate expansion involving fixed asset commitment. During the 1990s, the rolling-back of state ownership in the economy through privatization gathered considerable pace in the world. Privatization may play an important role in the ongoing transformation of capital markets in the world: due to its high profile, privatization may facilitate a switch from investment in bonds to investment in equities.

Questions

1Explain the globalization of financial markets.

2How has technology affected the globalization of financial markets?

3Why has the Eurocurrency market grown so rapidly?

4If Germany imposes interest rate ceilings on German bank deposits, what is the likely effect of this regulation on the euro interest rate?

5Why have bank regulators and market analysts expressed some concern about the stability of the interbank market?

6What is the difference between Eurobonds and foreign bonds?

7What is the difference between currency option bonds and currency cocktail bonds?

8Describe two new instruments: Euronotes and global bonds.

9Explain the Basel Accord of 1988.

10What is the major difference in the role of commercial banks in corporate governance between the USA and Japan?

11How can a government privatize state-owned companies?

12In April 2003, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision released for public comment the new Basel Capital Accord, which will replace the 1988 Capital Accord. What are the three pillars of this new proposal?

13What are some reasons for a company to crosslist its shares?

14The World Bank highlighted three aspects of the recent developing-country shift from debt to equity in its 2003 Global Development Finance. Briefly describe these three aspects of the shift.

288 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

Problems

1 Fill in the following blank spaces with a reserve ratio of 20 percent:

|

Acquired |

Required |

Excess |

Amount bank |

|

reserves |

reserves |

reserves |

can lend |

|

|

|

|

|

Bank 1 |

$100.00 |

$20.00 |

$80.00 |

$80.00 |

Bank 2 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 3 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 4 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 5 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 6 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 7 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 8 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 9 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 10 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 11 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 12 |

|

|

|

|

Bank 13 |

|

|

|

|

Total amount loaned |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2Assume that an international bank has the following simplified balance sheet. The reserve ratio is 20 percent:

Assets |

|

1 |

2 |

Liabilities and net worth |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reserves |

$4,400 |

– |

– |

Demand deposits $20,000 |

– |

– |

Securities |

7,600 |

– |

– |

|

|

|

Loans |

8,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(a)Determine the maximum amount that this bank can safely lend. Show in column 1 how the bank’s balance sheet will appear after the bank has loaned this amount.

(b)By how much has the supply of money changed?

REFERENCES 289

(c)Show the new balance sheet in column 2 after checks drawn for the entire amount of the new loans have been cleared against this bank.

(d)To what extent will this lending alter the supply of money?

(e)Aside from the leakage of required reserves at each stage of the lending process, there are some other leakages of money from the lending process. List and discuss them.

(f)Assume: (1) an American citizen transfers $2,000 of his deposits from a US bank to a Eurobank, and (2) Eurobanks as a whole keep 5 percent of their Eurodollar deposits in vault cash. Determine the maximum amount of Eurodollar supply that Eurobanks

can create on the basis of $2,000.

3A multinational company holds a $1,000 zero-coupon bond with a maturity of 15 years and a yield rate of 16 percent. What is the market value of the zero-coupon bond?

4A multinational company has issued a 10-year, $1,000 zero-coupon bond to yield 10 percent.

(a)What is the initial price of the bond?

(b)If interest rates dropped to 8 percent immediately upon issue, what would be the price of the bond?

(c)If interest rate rose to 12 percent immediately upon issue, what would be the price of the bond?

5A multinational company has common stock outstanding. Each share of the common stock pays $3.60 dividends per year, and the stockholder requires a 12-percent rate of return. What is the price of the common stock?

REFERENCES

Abken, P. A., “Globalization of Stock, Futures, and Options Markets,” in Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, ed., Financial Derivatives, 1993, pp. 3–24.

Bekaert, G., C. R. Harvey, and C. T. Lundblad, “Equity Market Liberalization in Emerging Markets,” Review, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July/Aug. 2003, pp. 53–80.

Butler, K. C., Multinational Finance, Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing, 1977, ch. 17.

International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, Washington, DC: IMF, Mar. 2003.

Karmin, C., “Decade Saw Vast Changes in Global Investing as the World’s Market Cap Surpassed its GDP,” The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 31, 1999, p. C12.

Lopez, J. A., “The Basel Proposal for a New Capital Adequacy Framework,” The Economic Newsletter,

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, No. 99-23, July 30, 1999.

Lopez, J. A., “Disclosure as a Supervisory Tool: Pillar 3 of Basel II,” The Economic Newsletter, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, No. 2003-22, Aug. 1, 2003.

“One World, How Many Stock Exchanges,” The Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2000, pp. C1, C20.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Financial Market Trends, Paris: OECD, Mar. 2003.

Saving, J. S., “Privatization and the Transition to a Market Economy,” Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Fourth Quarter 1999, pp. 17–24.

The World Bank, Global Development Finance, Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2003a.

The World Bank, Global Economic Prospects, Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2003b.

290 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

Case Problem 11: The Rise and Fall of the US Stock Market

The USA and Japan have long been like an old married couple. The USA likes to borrow and spend, while Japan likes to save and invest. And for almost 20 years, this odd relationship has endured, but not without strain. By the late 1990s, however, a new question came to the forefront: whether the world’s biggest saver would continue to provide relatively cheap capital to the world’s biggest spender.

It is no secret that the US economic expansion of the 1990s had been sustained with borrowed money abroad. American companies accrued huge debts, often to buy back company shares. American consumer debt is enormous, and continues to grow with no end in sight. And the spending boom has generated record trade deficits, including $500 billion in 2002. To finance current-account deficits, the USA has been forced to borrow approximately $2 billion every working day, most of which comes from foreign investors. For many years, only a small number of gloomy economists and investors worried aloud about this, but to no avail. By the late 1990s, however, many Japanese investors and policy-makers believed that US financial markets were in a bubble (see figure 11.6). US stock prices relative to earnings were high by historical standards. Various studies of stock market valuations concluded that by past standards the main US stock indices could be overvalued by some 20–40 percent. On the other hand, most Americans thought that US financial markets reflected fundamentals, until the US stock market collapsed in March 2000.

USA |

Germany |

Japan |

|||

600 |

|

600 |

|

600 |

|

450 |

|

450 |

|

450 |

|

300 |

Stock |

300 |

|

300 |

|

|

|

|

Stock |

||

|

|

|

Stock |

||

150 |

|

150 |

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

0 |

GDP |

0 |

GDP |

0 |

GDP |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

1980 |

1985 1990 1995 1999 |

1980 |

1985 1990 1995 1999 |

1980 |

1985 1990 1995 1999 |

Year

Figure 11.6 Stock prices and gross domestic product, inflation-adjusted, logarithmic scale, 1985 = 100

Source: The International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

|

CASE PROBLEM 11 |

291 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

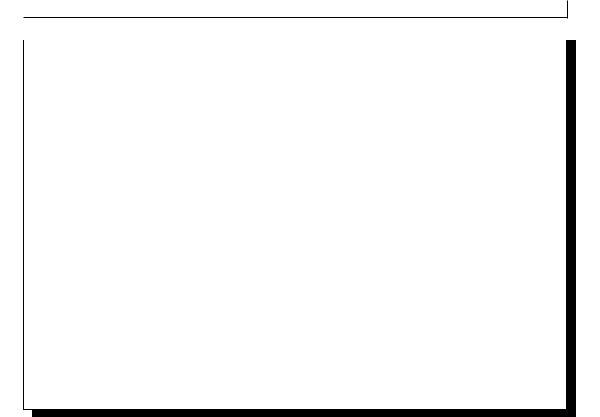

Table 11.7 The performance of the major US stock indexes

Index |

2003 |

2002 |

2001 |

2000 |

1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dow Jones |

+0.25 |

-0.17 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

+0.25 |

Standard & Poor’s 500 |

+0.26 |

-0.23 |

-0.13 |

-0.10 |

+0.20 |

NASDAQ Composite |

+0.50 |

-0.31 |

-0.21 |

-0.39 |

+1.02 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: “Stocks Post First Winning Year Since 1999,” www.cnn.com,

Jan. 1, 2004.

Japanese and other foreign investors continue to fund the US economy even today, but the boom in the US economy and its stock market ended in March 2000. In addition, as war and terrorism fears mount, nobody thinks that this kind of inflow can be sustained indefinitely

– a change that may boost the inflation rate and hurt corporate profits, the US dollar, and investment returns. The financial reversal would also bring the collapse of the US security policy and of its calculated strategy of world pacification.

In 2003, all US stock indexes recorded their strongest rally since the Internet bubble burst in March 2000. Table 11.7 shows that all three major stock indexes – the Dow Jones, Standard & Poor’s 500, and the NASDAQ Composite – posted their first annual gains since 1999. Nevertheless, the NASDAQ Composite Index of 2,000 at the end of 2003 was still 60 percent lower than its peak of 5,000 in 1999. Furthermore, some portfolio managers, such as Richard Bernstein of Merrill Lynch, argued that US stocks were so overpriced that they could fall as much as 14 percent in 2004. No wonder some pros continue to feel uncomfortable as they return from the beach. The worry is that investors have overdone things again. The stock market appears to feel like “the mania-inspired environment of the late 1990s,” a time in which investors ignored repeated warning signs. Factors such as rising interest rates, overaggressive earnings forecasts, and more violence in Iraq could ruin the stock market rally again.

There are new concerns that the current US economy may follow Japan’s trail of the 1990s. Figure 11.7 shows that the patterns of the Nikkei 225 and the NASDAQ indices before and after their booms and bursts are strikingly similar. Lingering possibilities of deflation and low interest rates intensify the worry. Some experts say that the US economy is different from Japan’s in several ways and thus will not follow Japan’s trail.

Case Questions

1What is a bubble?

2Japanese investors and policy-makers believed that the US financial markets of the late 1990s were in a bubble. On the other hand, most Americans thought that US financial markets reflected market fundamentals. Why were Japanese people so sensitive to asset bubbles?