Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

922

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

|

B |

|

|

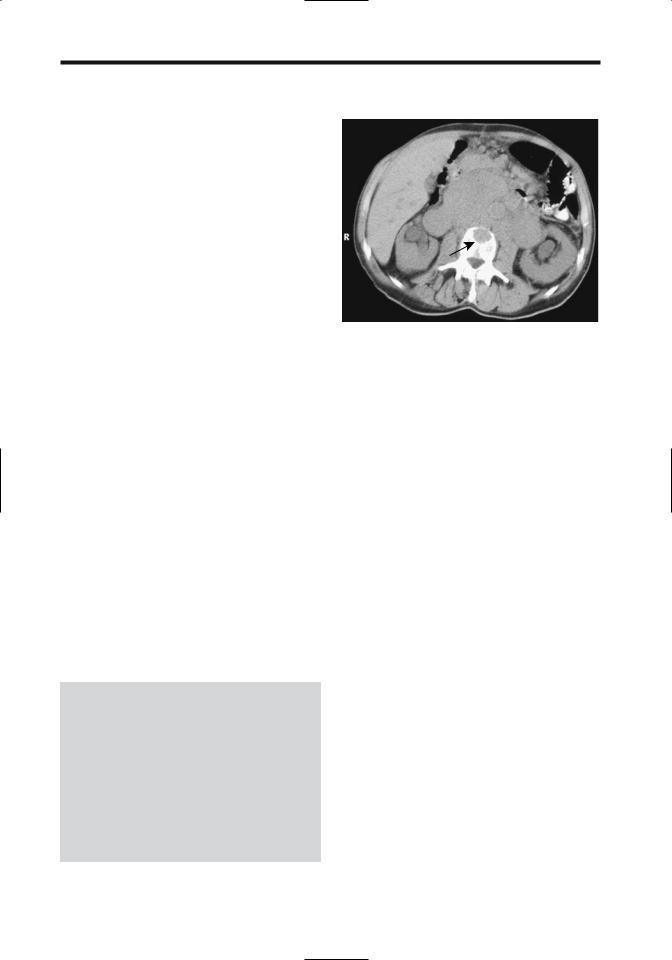

Figure 14.32. A: Abdominal wall hernia containing stomach. The |

|

|

gastric body and antrum extend anteriorly through a hiatus |

|

|

(arrow). B: Ventral hernia identified with CT (arrow). The hernia |

|

|

had been growing and an adenocarcinoma was found during |

|

|

hernia repair, believed to be secondary to a previously resected |

|

A |

colon cancer. |

|

wide hiatus. A barium study detects bowel |

others are detected with a small bowel barium |

|

herniation. |

study. A retrograde barium study through the |

|

These hernias are somewhat difficult to |

stoma is often helpful in outlining these hernias. |

|

repair because of their wide hiatus and because |

|

|

the surrounding structures tend to be weak. At |

|

|

times extraperitoneal fixation of a prosthetic |

Internal Hernia |

|

mesh to the 12th rib superiorly and iliac crest |

|

|

inferiorly is necessary. |

Patients with an internal hernia range from |

|

|

those who are asymptomatic, to those who have |

|

Sciatic Foramen Hernia |

intermittent nonspecific symptoms, to those |

|

|

who have small bowel obstruction. Especially |

|

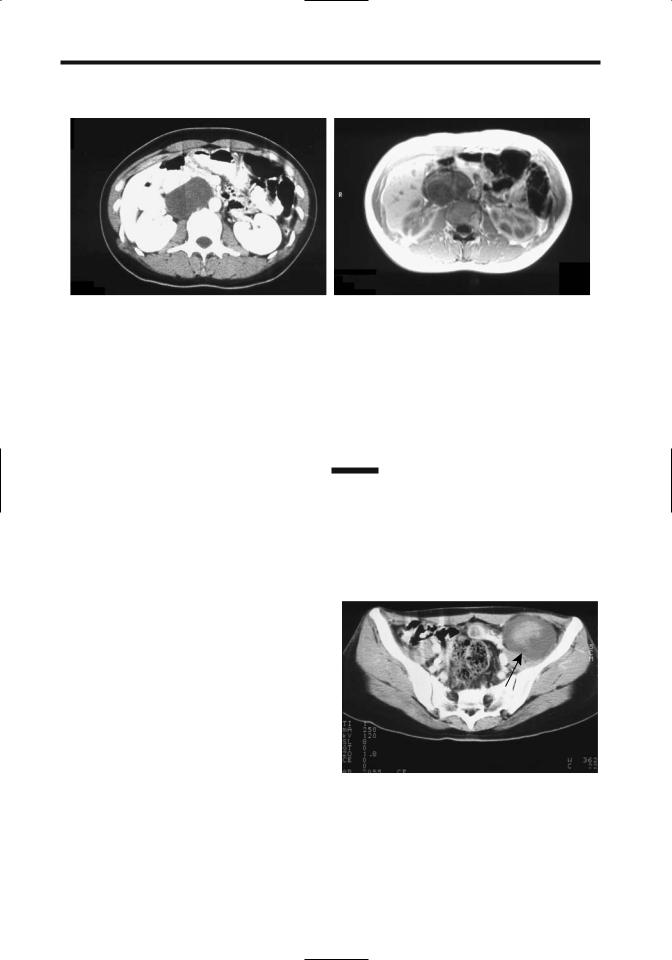

In a sciatic foramen hernia a loop of bowel or |

when intermittent, these hernias are difficult to |

|

adjacent tissue herniates through one of the |

diagnose with either barium studies or CT. |

|

sciatic foramina posteriorly. Bowel obstruction |

At times only a vague point of obstruction, |

|

and strangulation ensue. These hernias are |

either partial or complete, is identified with |

|

rare. |

imaging, but the etiology of obstruction is not |

|

Sciatic hernias are a cause of chronic pelvic |

evident. |

|

pain in women; most are left sided, and a rare |

Computed tomography findings of sympto- |

|

one can even contain an ovary and fallopian |

matic internal hernias consist of small bowel |

|

tube. Computed tomography or MRI should |

obstruction, a focal collection of dilated bowel |

|

identify the hernial content. |

displacing adjacent bowel, and stretched and |

|

|

displaced mesenteric vessels. |

|

Incisional Hernia |

Peritoneoceles and enteroceles are discussed |

|

|

in Chapter 5. Cystoceles are discussed in |

|

Either omentum or part of the stomach or bowel |

Chapter 11. |

|

can be part of an incisional hernia (Fig. 14.32). |

|

|

CT should detect these hernias, except that |

Transmesenteric Hernia |

|

some hernias reduce with the patient supine. A |

||

|

||

barium study detects herniation if it includes |

A transmesenteric hernia is the most common |

|

stomach or bowel. |

internal hernia. Although its appearance varies |

|

A parastomal hernia is a type of incisional |

considerably, the presence of dilated small |

|

hernia occurring alongside an intestinal stoma |

bowel loops close to the abdominal wall without |

|

on the abdominal wall. Some of these hernias |

overlying omental fat should suggest this diag- |

|

are evident on physical examination while |

nosis (73). Associated small bowel volvulus and |

D

D B

B