Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

852

nous route. Overall, metastases to the testes are uncommon. Prostatic, appendiceal or colonic signet ring carcinomas and a rare renal cell carcinoma have spread via the spermatic cord. Anecdotal metastatic bile duct carcinomas are reported.

Metastases tend to be multiple. Ultrasonography reveals variable echogenicity.

Lymphoma/Leukemia

Primary testicular lymphoma occurs in all age groups but is not common. In distinction to other testicular tumors, secondary lymphoma occurs in older men; lymphoma should be considered if an elderly man develops a testicular tumor. Almost all secondary malignant lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas. In an occasional patient testicular lymphoma is a first manifestation for this tumor.

Lymphomas and leukemic involvement tend to be bilateral. They range from focal to diffuse infiltration. Ultrasonography reveals a hypoechoic, homogeneous focal or diffuse tumor, similar to germ cell tumors. Associated adenopathy is common, and the epididymis and spermatic cord are also often involved.

Lymphomas tend to be hypointense relative to hydrocele fluid on MR. Similar to lymphomas elsewhere, a homogeneous appearance is common.

Testicular involvement in leukemia is common, especially during recurrence. During remission leukemic cells may persist in the testis in spite of adequate chemotherapy. Leukemia manifests as testicular enlargement. Imaging reveals diffuse infiltration, similar to primary tumors.

Myeloma

A testicular plasmacytoma is rare. It is more common to find testicular infiltration as part of multiple myeloma.

Hemangioma

Both testicular and extratesticular cavernous hemangiomas are rare, and only anecdotal reports exist. Most are detected as palpable nodules and a malignancy is suspected clinically. Hemangiomas have similar imaging findings to the unrelated rare paratesticular

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

epithelioid hemangioendothelioma; it has a good prognosis.

Ultrasonography of hemangiomas ranges from nondiagnostic to a heterogeneous tumor replacing parenchyma. Most are hypoechoic, but their echogenicity varies. Some hemangiomas contain calcifications. Color Doppler US of one revealed intense flow in the tumor and normal flow in the surrounding parenchyma (86). Ultrasonography of extratesticular hemangiomas tends to suggest a varicocele.

These hemangiomas are slightly hyperintense on T1and markedly hyperintense on T2weighted images. Any thrombi appear as signal voids.

Extratesticular Tumors

Ultrasonography can differentiate most testicular from extratesticular tumors. Whether an extratesticular tumor originates from the epididymis is more problematic. Ultrasonography cannot differentiate the considerably more common benign extratesticular tumors from a malignant one.

Mesenchymal Tumors

Lumped under this heading are mesotheliomaorigin tumors, various sarcomas, and their benign counterparts. Most originate in the spermatic cord or epididymis. Some undoubtedly are a component of a teratoma.

Over 90% of spermatic cord neoplasms are of mesenchymal origin.

Adenomatoid Tumor/Nonpapillary

Benign Mesothelioma

The most common benign neoplasm involving epididymis is an adenomatoid tumor, also known as a nonpapillary benign mesothelioma. A rare adenomatoid tumor originates in the testis or spermatic cord. Immunohistochemical study suggests a mesothelial cell origin (87). Occurring in adults, these slow-growing tumors are most common in young men; many are asymptomatic.

These tumors vary in their imaging appearance. Most are solid and well marginated, but an occasional one is predominantly cystic. Varying amounts of fibrosis are common. They range from hyperto mostly isoechoic in appearance.

853

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

Some invade adjacent testis and mimic a carcinoma, although testicular malignancies do not typically have an isoechoic appearance.

Malignant Mesothelioma

Malignant mesotheliomas of the tunica vaginalis are uncommon, affecting men over age 50 years.Anecdotal synchronous bilateral malignant mesotheliomas are reported. An association exists with prior asbestos exposure. These tumors range from an aggressive course to more indolent ones. Histologic differentiation from a benign adenomatoid tumor is difficult.

These are solid, nodular tumors. They spread primarily via lymphatics; one of the few remaining indications for a lymphogram is in the workup of a malignant mesothelioma.

Complete tumor excision should be curative.

Benign Mesenchymal Tumors

Lipomas are common extratesticular and spermatic cord tumor. Some of these tumors are complex, containing other mesenchymal tissue. Occurring over a wide age range, many are discovered incidentally.

A lipoma appears as fat density on CT and as a hyperechoic tumor on US. Magnetic resonance reveals a relatively homogeneous hyperintense tumor on T1-weighted images; some lipomas are hyperintense to fat on T2-weighted images.

A rare scrotal tumor of unknown etiology consists primarily of fibrosis and is nonneoplastic in origin. Most of these fibromas are hyperechoic on US. Some have a striated appearance. Magnetic resonance reveals a hypointense tumor on T1and an inhomogeneous hypointense tumor on T2-weighted images. They tend to have inhomogeneous contrast enhancement.

Aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) of the spermatic cord is rare; histologically these tumors are similar to other desmoid tumors found in the abdomen and are associated with Gardner’s syndrome. These tumors recur following local excision.

Sarcoma

Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas occur in infants and children, while leiomyosarcomas

are more common in adults. Rhabdomyosarcomas are mostly solid and occasionally partly cystic, and mimic benign neoplasms. A rhabdomyosarcoma should be considered in children with a paratesticular cystic tumor containing a solid component. Some of these tumors are associated with a hydrocele.

The rare liposarcoma is most common in the spermatic cord (88); some are associated with surrounded inflammation and fibrosis.

The term malignant mesenchymoma appears appropriate for some of these tumors; an occasional one contains such elements as a liposarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and even osteosarcoma.

With most of these tumors preoperative imaging discloses a nonspecific intrascrotal, paratesticular tumor. Ultrasonography and MR reveal a homogeneous tumor indistinguishable but separate from a normal testis. A similar appearance is seen with benign mesenchymal tumors, which, statistically, are more common in this location.

A rare paratesticular tumor is reactive pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation (proliferative funiculitis). It is of unknown etiology, although prior trauma appears to be a factor.

Adenoma

Histologically, an adenoma is similar to a welldifferentiated renal cell carcinoma and a multicystic papillary adenocarcinoma of the rete testis, thus metastasis is in the differential diagnosis. This tumor is associated with von HippelLindau disease, at times occurring bilaterally. In the presence of other, more ominous systemic tumors found in von Hippel-Lindau disease, most of these cystadenomas are asymptomatic.

These adenomas range from solid to mostly cystic with papillary soft tissue projections.

Metastasis

Detection of an epithelial malignant neoplasm in the spermatic cord most often represents a metastasis. Even in an asymptomatic patient, a search for a primary site is warranted. A spermatic cord adenocarcinoma is occasionally a first manifestation of a silent colon cancer.

854

Calcifications

Testicular

The term microlithiasis implies microscopic calcifications that should not be visible with imaging, but this term has become ingrained in medical and radiologic usage for the faint, barely perceptible calcifications detected with high-resolution imaging and is used in this context here. Pathologically, these calcifications either consist of amorphous calcific debris or, more often, are laminated (77); most are multiple. They appear to represent a defect in Sertoli cell phagocytosis of tubular debris. The prevalence of testicular microlithiasis in a population referred for scrotal US was <1% (89).

Testicular calcifications occur in a number of benign conditions and malignancies, in boys and in adults (Table 13.8). In some individuals microlithiasis is discovered as an incidental finding. The relative risk of a concurrent tumor being present is about 22-fold compared to controls (89). Some calcifications are premalignant; neoplasms developing later in some of these individuals, with time interval between discovery of microlithiasis and subsequent neoplasm detection ranging up to a decade.

Table 13.8. Conditions associated with testicular calcifications

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Typically, US reveals testicular microlithiasis as numerous diffuse, small, nonshadowing hyperechoic foci throughout the parenchyma. A tendency toward a peripheral location is evident with some. Any clustering of calcifications should suggest a malignancy.

Although the approach to incidentally discovered microlithiasis varies, an initial clinical evaluation for a silent malignancy, including CT of the chest and abdomen, appears reasonable. Some investigators follow these patients with serial imaging and tumor markers (a- fetoprotein and b-hCG), although sufficient data are not available to provide firm recommendations.

Extratesticular

Prostatic calcifications are common. Occasionally during a bone scan uptake of Tc-99m- MDP, radiotracer is detected around prostatic calcifications; presumably this tissue is metabolically active.

Calcifications develop in some extratesticular benign tumors. The sequela of a hematocele has already been mentioned. Some calcifications are loose in the tunica vaginalis sac; the literature refers to these as scrotal pearls. An occasional such calcification floats in a hydrocele.

Idiopathic

Cryptorchidism

Klinefelter’s syndrome

Down syndrome

Infection/inflammation

Tuberculosis

Filariasis

Granulomatous orchitis

Sarcoidosis

Neoplasms

In association with pulmonary microlithiasis

Epidermoid cysts

Ischemia

Trauma

Prior testicular torsion

Vasculitis

Hematoma

Infertility

Vascular Abnormalities

Varicocele (Spermatic Vein)

Clinical

A varicocele consists of either a single enlarged vein or several freely communicating veins containing incompetent valves. The primary importance of a varicocele is its association with infertility and testicular hypotrophy, although at times a varicocele leads to pain. Only a minority of men with a varicocele are infertile, however, and it is not possible to predict among teenagers with a newly discovered varicocele who will become infertile.

In younger men most varicoceles are idiopathic, but a secondary cause is more common in older individuals. At times an extrinsic tumor, such as a left-sided renal cell carcinoma, compresses or occludes the testicular vein and

855

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

first manifests as a left varicocele. Rarer conditions include hydronephrosis and malignant lymphadenopathy adjacent to the veins.

Varicocele prevalence gradually increases in teenagers, reaching adult levels at about the age of 18 years. In the pediatric age group a varicocele is often associated with a small testis. Testicular growth can be expected after therapy. In infertile men with varicoceles both testicles tend to be atrophic, and sperm motility is low. Correction of a varicocele in an adult often produces poor results, thus the emphasis on early detection.

Varicoceles are more common on the left, although in infertile men varicoceles are most often bilateral. A large study found 87% of individuals to have left varicoceles only, 2% right varicoceles, and 11% bilateral varicoceles (90). The more common left varicocele typically drains into the left renal vein. With an isolated right varicocele, compression of the right spermatic vein by an extrinsic tumor should be considered. Most right varicoceles join the inferior vena cava just inferior to the right renal vein, but aberrant drainage pathways are not uncommon; communication with the paravertebral veins or portal venous system, especially left colic vein, is found in a minority (91). Detection of these alternate pathways aids in reducing recurrence after therapy. A minority of varicoceles are intratesticular in location.

Idiopathic thrombosis of a varicocele is rare (92); clinically, on an acute basis it mimics a strangulated inguinal hernia or testicular torsion.

Imaging

Gray-scale US reveals most varicoceles as dilated, tubular blood-filled structures. Venography identifies testicular (internal spermatic) vein insufficiency by showing reflux of contrast from the left renal vein into the testicular vein and pampiniform plexus.

The internal spermatic vein becomes palpable at a diameter of about 3 to 3.5mm and Doppler US detects reversal of venous blood flow in veins wider than about 3.5mm, realizing that clinical and US diagnoses of a varicocele do not always agree. Although Doppler US does detect a subclinical varicocele, its sensitivity probably is less than that of venography. Also,

the borderland between normal diameter and a varicocele is not clearly defined. Does venous reflux always signify a varicocele?

A rare varicocele is intratesticular and simply represents a dilated intratesticular vein. These intratesticular varicoceles range from bilateral to unilateral, and about half are not associated with an extratesticular varicocele. Ultrasonography detects these varicoceles as dilated serpiginous intratesticular veins close to the mediastinum testis. Doppler US confirms a lowflow state, which varies with the Valsalva maneuver. Care is necessary with US to differentiate between an intratesticular varicocele and tubular ectasia.

Magnetic resonance imaging of an intratesticular varicocele reveals a tortuous tubular structure hypointense on T1and T2-weighted images; it had the same signal intensity as testicular parenchyma. The more common extratesticular varicoceles have a serpiginous course and a varied signal intensity, depending on flow. They enhance on immediate postcontrast images.

Scintigraphy is not commonly used to evaluate varicoceles. Occasionally detected is retrograde blood flow in the internal spermatic vein. Relative blood-pool activity in each hemiscrotum appears to correlate with the presence of a palpable varicocele, but the relevance of such scintigraphy is not established.

Venography not only detects a varicocele but also is used for therapy. Detachable balloons, coils, and a number of foreign materials have been tried with varying success rates.

During a Valsalva maneuver while upright, infrared thermometry reveals an increase in scrotal temperature in those with a varicocele; after internal spermatic vein ligation, the scrotal temperature decreases to that of controls.

Therapy

Considerable evidence suggests that early varicocele treatment in pubertal boys prevents testicular growth arrest. Even in adolescents with grade 2 or 3 varicoceles, within a year of varicocele repair the involved testis increases in size. The goal of therapy in individuals with infertility is to improve sperm density and sperm motility. Varicocelectomy even of a unilateral varicocele results in an improvement.

856

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

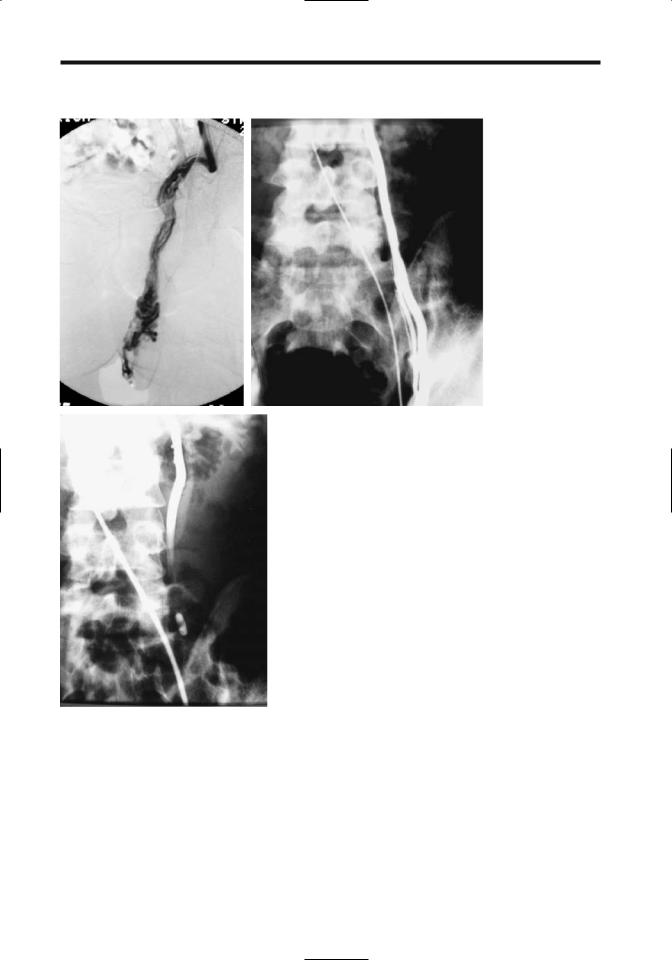

A B

|

Figure 13.12. Left varicocele embolization. A: The left spermatic vein and |

|

pampiniform plexus are markedly dilated. B: The spermatic vein was catheter- |

|

ized via the left renal vein and contrast injected. C: Spermatic vein is occluded |

|

with a detachable balloon. (Courtesy of Oscar Gutierrez, M.D., University of |

C |

Chile, Santiago, Chile.) |

Prior to therapy, it appears worthwhile to ensure that the underlying kidney is normal. Traditional therapy of a varicocele is open extraperitoneal repair. Recurrence is greater with spermatic vein ligation, but the risk of major complications, including testicular ischemia and hydrocele, increases with spermatic cord venous channel ligation. Currently percutaneous embolization using either stain-

less steel occluding spring coils or sclerotherapy is more common.Alternative therapy consists of detachable embolization balloons and laparoscopic varicocelectomy (Fig. 13.12). Initial spermatic vein phlebography helps establish underlying anatomic variants Current evidence suggests that in infertile men no significant difference in outcome exists between surgical ligation and percutaneous embolization.

857

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

A long-term study of almost 1500 patients with varicoceles using basilic vein access achieved a success rate of 82% for sclerotherapy and 84% for a combination of sclerotherapy and embolization (90); therapy could not be performed in 7% of patients due to basilic vein spasm, catheterization difficulties, or anatomic variation. Some published successful percutaneous varicocele treatment rates are >90%.

Persisting or recurrent varicoceles are generally due to collateral vessels. A combination of endovascular occlusive metal coils—which is comparable with surgical ligation, and a sclerosing agent—which diffuses and scleroses collateral veins and thus decreases recurrence, appears superior to separate use of these agents. Others embolize silicone or latex balloons combined with a sclerosing agent.

An intratesticular varicocele was treated by transcatheter embolization of the spermatic vein (93).

Is an intraoperative postligation venogram necessary during varicocelectomy to confirm the completeness of varicocele ligation? Among boys with postoperative recurrent varicoceles, the presence of patent collateral veins missed at initial surgical ligation caused recurrence in 68%, ineffective vein ligation in 27%, and incompetence of extrafunicular plexus in 5% (94); missed collateral veins were due to the presence of either a double or triple spermatic vein, venous bridges across the surgical ligation, or extraperitoneal anastomoses. A minority of individuals have anastomoses with the portal or systemic veins— among others, with the left colic vein, paravertebral venous plexus, inferior mesenteric veins, and splenic veins (91). Following surgical correction, recurrence usually consists of collateral vessels running parallel to the original varicocele. Knowledge of underlying anastomoses is necessary to prevent recurrence after therapy.

Instead of a venogram, some surgeons use Doppler US to identify accessory spermatic veins and evaluate surgical results.

Prostatodynia (Pelvic Venous

Congestion)

Prostatodynia signifies pain referable to the prostate. The relationship between prostatitis

and prostatodynia is murky, and the latter term is occasionally used to describe clinically atypical prostatitis. Prostatodynia is a clinical diagnosis while pelvic venous congestion is an objective finding based on imaging data. Although many men with prostatodynia do have pelvic venous congestion, these terms are not synonymous.

Endorectal US and transperineal color Doppler US detects intrapelvic venous congestion. Typical 3D MR venography findings of pelvic venous congestion consist of dilated and often thickened prostatic capsular veins, pudendal plexus, and the plexus posterior to the bladder. Three-dimensional MR images provide a global view.

Ischemia

The most common cause of testicular ischemia and atrophy is testicular torsion (discussed earlier; see Testicular Torsion). Penile gangrene and necrosis develop in patients with chronic renal failure; presumably gangrene is ischemic in nature due to progressive vascular calcifications (calciphylaxis) induced by secondary hyperparathyroidism developing with chronic renal failure. Other causes include infection, trauma, and some vasculitides, such as polyarteritis nodosa. Emphysematous infarction is a complication of epididymo-orchitis. Testicular infarction develops in sickle cell disease. A relatively new diagnosis is segmental testicular infarction; MR appears to be the imaging modality of choice for this condition, which is treated with watchful waiting and which reveals eventual partial or complete revascularization (95,96). Penile necrosis has been reported after coronary artery bypass graft (97).

Neonatal testicular infarction is rare. These infarctions can be segmental.

Imaging findings early in the course of an infarction tend to mimic those of a neoplasm. Scintigraphic appearance (using Tc-99m- pertechnetate) of scrotal cellulitis has simulated testicular infarction (98).

Ultrasonography of an infarction reveals a diffuse, inhomogeneous echo pattern. At this stage Doppler US reveals hypoperfusion. Without adequate therapy the testes eventually atrophies and often dystrophic calcifications develop.

858

Leriche’s Syndrome

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can detect Leriche’s syndrome (occlusion of distal aorta) and, in fact, often provides better femoral artery visualization than does intraarterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA). A 3D MRA classification of Leriche’s syndrome is based on the level of aortic occlusion: (1) juxtarenal; (2) infrarenal but cranial to the inferior mesenteric artery origin; and (3) caudal to the inferior mesenteric artery (99).

Acquired Immune Deficiency

Syndrome (AIDS) Related

Prostatic tubercular abscesses develop in men with AIDS. Epididymo-orchitis is not uncommon and tends to be more severe than in non-AIDS patients. Unusual opportunistic pathogens are common. At times MRI reveals obliteration of interlobular septa and mimics a cancer. Some of these infections evolve into an epididymocutaneous fistula.

Testicular stromal tumors have developed in HIV-infected men. Fournier’s gangrene can also be initial presentation of an HIV patient.

Postoperative Changes

Prostate

A false urethral passage may not fill with contrast after prostatic surgery and thus be missed on a voiding cystourethrogram. At times an introduced catheter elevates an adjacent mucosal flap and identifies the false passage. If needed, US is useful for guidance in inserting a catheter.

Urinary incontinence is a complication after prostatectomy. Evaluation of the bladder outlet sphincter mechanism in these patients is discussed in Chapter 11.

Anecdotal reports describe a gossypiboma (retained surgical sponge) after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection resulting in recurrent bladder neck strictures.

Similar to other surgical procedures, a radical retropubic prostatectomy is associated with thromboembolic complications. Pelvic lympho-

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

celes and hematomas appear to have a role in thrombi formation; postoperative pelvic US detects most lymphoceles and hematomas, although small collections are overlooked.

Postvasectomy

A vasectomy is associated with few complications. Granulomas and cysts develop postvasectomy. Granulomas are probably secondary to spermatozoal extravasation and a resultant inflammatory response. Extravasation presumably is secondary to increased pressure in epididymal tubules. The epididymis enlarges.

A granuloma appears as a hypoechoic tumor within either the epididymis or adjacent structures.

Postbiopsy

Arteriovenous fistulas, detectable with color Doppler US, occur with a minority of endorectal prostate needle biopsies; almost all of these fistulas close spontaneously.

Similar to other sites, US-guided transperineal prostatic biopsy can result in perineal tumor implantation.

Testicular US after testicular biopsy reveals a range of findings, such as focal hypoechoic tumors ranging from well marginated to poorly defined, peritesticular hyperechoic foci or linear striations, and focal contour defects (100); some of these findings even suggest a neoplasm, and thus knowledge of a past biopsy is necessary.

Other Findings

After a pancreas–kidney transplant, with the exocrine pancreatic drainage into the bladder, anecdotal reports describe urethral disruption, presumably secondary to enzymatic digestion.

Vesicourethral dysfunction is a complication of radical rectal surgery. The bladder does not empty normally. Radical transurethral prostate resection appears effective in some.

References

1.Mate A, Bargiela A, Mosteiro S, Diaz A, Bello MJ. Contrast ultrasound of the urethra in children. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1534–1537.

859

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

2.Seki N, Senoh K, Kubo S, Tsunoda T. Congenital megalourethra: a case report. Int J Urol 1998;5:191– 193.

3.Aggarwal A, Krishnan J, Kwart A, Perry D. Noonan’s syndrome and seminoma of undescended testicle. South Med J 2001;94:432–434.

4.Nicolas F, Dubois R, Laboure S, Dodat H, Canterino I, Rouviere O. [Testicular microlithiasis and cryptorchism: ultrasound analysis after orchidopexy.] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:357–361.

5.Lam WW, Tam PK, Ai VH, Chan KL, Chan FL, Leong L. Using gadolinium-infusion MR venography to show the impalpable testis in pediatric patients. AJR 2001;176:1221–1226.

6.Robert F, Rollet J, Lapray JF, Bey-Omar F, Durieu I, Morel Y. [Agenesis of the vas deferens in male infertility. A tentative classification based on 39 cases.] [French] Presse Med 1999;28:116–121.

7.Stikkelbroeck NM, Suliman HM, Otten BJ, Hermus AR, Blickman JG, Jager GJ. Testicular adrenal rest tumours in postpubertal males with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: sonographic and MR features. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1597–1603.

8.Avila NA, Premkumar A, Merke DP. Testicular adrenal rest tissue in congenital adrenal hyperplasia: comparison of MR imaging and sonographic findings. AJR 1999;172:1003–1006.

9.Goldman SM, Sandler CM, Corriere JN Jr, McGuire EJ. Blunt urethral trauma: a unified, anatomical mechanical classification. [Review] J Urol 1997;157:85– 89.

10.Uder M, Gohl D, Takahashi M, et al. MRI of penile fracture: diagnosis and therapeutic follow-up. Eur Radiol 2002;12:113–120.

11.Dee KE, Deck AJ, Waitches GM. Intratesticular pseudoaneurysm after blunt trauma. AJR 2000;174: 1136.

12.Frauscher F, Klauser A, Stenzl A, Helweg G, Amort B, zur Nedden D. Ultrasonography findings in the scrotum of extreme mountain bikers. Radiology 2001;219:817–821.

13.Mueller-Lisse UG, Frimberger M, Schneede P, Heuck AF, Muschter R, Reiser MF. Perioperative prediction by MRI of prostate volume six to twelve months after laser-induced thermotherapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001; 13:64–68.

14.Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H, Eberhardt SC, et al. Chronic prostatitis: MR imaging and 1H MR spectroscopic imaging findings–initial observations. Radiology 2004;231:717–724.

15.Tisseau L, Zini L, Lemaitre L, Biserte J, Gosselin B, Leroy X. [Prostatic malacoplakia: report of 3 cases.] [French] Prog Urol 2000;10:597–599.

16 Halpern EJ, Hirsch IH. Sonographically guided transurethral laser incision of a Mullerian duct cyst for treatment of ejaculatory duct obstruction. AJR 2000;175:777–778.

17.Francica G, Bellini S, Miragliuolo A. Schwannoma of the prostate: ultrasonographic features. Eur Radiol 2003;13:2046–2048.

18.Stamey TA, Donaldson AN, Yemoto CE, McNeal JE, Sozen S, Gill H. Histological and clinical findings in 896 consecutive prostates treated only with radical retrop-

ubic prostatectomy: epidemiologic significance of annual changes. J Urol 1998;160:2412–2417.

19.Villers A, Soulie M, Haillot O, Boccon-Gibod L. [Prostate cancer screening (III): risk factors, natural history, course without treatment. Characteristics of detected cancers.] [Review] [French] Prog Urol 1997;7: 655–661.

20.Vantaux P, Schneider P, Le Coz S, Villers A. [Consumption coagulopathy disclosing prostatic cancer.] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:68–69.

21.Valeri A, Drelon E, Azzouzi R, et al. [Epidemiology of familial prostatic cancer: 4-year assessment of French studies.] [French] Prog Urol 1999;9:672–679.

22.Hoedemaeker RF, van der Kwast TH, Boer R, et al. Pathologic features of prostate cancer found at popu- lation-based screening with a four-year interval. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1153–1158.

23.Hugosson J, Aus G, Becker C, et al. Would prostate cancer detected by screening with prostate-specific antigen develop into clinical cancer if left undiagnosed? A comparison of two population-based studies in Sweden. BJU Int 2000;85:1078–1084.

24.Benchekroun A, Zannoud M, Ghadouane M, Alami M, Belahnech Z, Faik M. [Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate.] [Review] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:327– 330.

25.Lilleby W,Torlakovic G,Torlakovic E,Skovlund E,Fossa SD. Prognostic significance of histologic grading in patients with prostate carcinoma who are assessed by the Gleason and World Health Organization grading systems in needle biopsies obtained prior to radiotherapy. Cancer 2001;92:311–319.

26.Rubin MA, Dunn R, Kambham N, Misick CP, O’Toole KM. Should a Gleason score be assigned to a minute focus of carcinoma on prostate biopsy? Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1634–1640.

27Bocking A. [Cytopathology of the prostate.] [Review] [German] Pathologe 1998;19:53–58.

28.Prando A, Wallace S. Helical CT of prostate cancer: early clinical experience. AJR 2000;175:343–346.

29.Halpern EJ, Strup SE Using gray-scale and color and power Doppler sonography to detect prostatic cancer. AJR 2000;174:623–627.

30.Kuligowska E, Barish MA, Fenlon HM, Blake M. Predictors of prostate carcinoma: accuracy of gray-scale and color Doppler US and serum markers. Radiology 2001;220:757–764.

31.Halpern EJ, Rosenberg M, Gomella LG. Prostate cancer: contrast-enhanced US for detection. Radiology 2001; 219:219–225.

32.Lagalla R, Caruso G, Urso R, Bizzini G, Marasa L, Miceli V. [The correlations between color Doppler using a contrast medium and the neoangiogenesis of small prostatic carcinomas.] [Italian] Radiol Med 2000;99: 270–275.

33.Ikonen S, Karkkainen P, Kivisaari L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of clinically localized prostatic cancer. J Urol 1998;159:915–919.

34.Cruz M, Tsuda K, Narumi Y, et al. Characterization of low-intensity lesions in the peripheral zone of prostate on pre-biopsy endorectal coil MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2002;12:357–365.

35.Scheidler J, Hricak H, Vigneron DB, et al. Prostate cancer: localization with three-dimensional proton

860

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

MR spectroscopic imaging—clinicopathologic study. Radiology 1999;213:473–480.

36.Picchio M, Landoni C, Messa C, et al. Positive [11C]choline and negative [18F]FDG with positron emission tomography in recurrence of prostate cancer. AJR 2002;179:482–484.

37.Garcia G, Chevallier D, Amiel J, Toubol J, Michiels JF. [Prospective study comparing ultrasonography guided trans-rectal biopsy and finger guided trans-perineal biopsy in the diagnosis of prostatic cancer.] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:40–43.

38.Melchior SW, Noteboom J, Gillitzer R, Lange PH, Blumenstein BA, Vessella RL. The percentage of free prostate-specific antigen does not predict extracapsular disease in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer before radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2001;88: 221–225.

39.Miller JS, Puckett ML, Johnstone PA. Frequency of coexistent disease at CT in patients with prostate carcinoma selected for definitive radiation therapy: is limited treatment-planning CT adequate? Radiology 2000;215:41–44.

40.Kuhn M, Huttmann P, Spielhaupter E, Gross-Fengels W, Schreiter F. [Clinical value of native and contrast enhanced MRI in staging prostatic carcinoma before planned radical prostatectomy.] [German] Rofo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Neuen Bildgeb Verfahr 2001; 173:595–600.

41.Wang L, Mullerad M, Chen HN, et al. Prostate cancer: incremental value of endorectal MR imaging findings for prediction of extracapsular extension. Radiology 2004;232:133–139.

42.Qayyum A, Coakley FV, Lu Y, et al. Organ-confined prostate cancer: effect of prior transrectal biopsy on endorectal MRI and MR spectroscopic imaging. AJR 2004;183:1079–1083.

43.Schettino CJ, Kramer EL, Noz ME, Taneja S, Padmanabhan P, Lepor H. Impact of fusion of indium111 capromab pendetide volume data sets with those from MRI or CT in patients with recurrent prostate cancer. AJR 2004;183:519–524.

44.Dunzinger M, Sega W, Madersbacher S, Schorn A. Predictive value of the anatomical location of ultrasoundguided systematic sextant prostate biopsies for the nodal status of patients with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 1997 31:317–322.

45.Amsellem D,Ogiez N,Salomon L,Chopin D,Abbou CC, Colombel M. [Does PSA of less than 20ng/ml exclude the diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer?] [French] Prog Urol 1998;8:1018–1021.

46.Epstein JI, Chan DW, Sokoll LJ, et al. Nonpalpable stage T1c prostate cancer: prediction of insignificant disease using free/total prostate specific antigen levels and needle biopsy findings. [Review] J Urol 1998;160: 2407–2411.

47.Soulie M, Grosclaude P, Villers A, et al. [Variations of the practice of radical prostatectomy in France.] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:49–55.

48.Theodorescu D, Gillenwater JY, Koutrouvelis PG. Prostatourethral-rectal fistula after prostate brachytherapy. Cancer 2000;89:2085–2091.

49.Coakley FV, Hricak H, Wefer AE, Speight JL, Kurhanewicz J, Roach M. Brachytherapy for prostate

cancer: endorectal MR imaging of local treatmentrelated changes. Radiology 2001;219:817–821.

50.Seifert JK, Morris DL. World survey on the complications of hepatic and prostate cryotherapy. World J Surg 1999;23:109–113.

51Chen JC, Moriarty JA, Derbyshire JA, et al. Prostate cancer: MR imaging and thermometry during microwave thermal ablation-initial experience. Radiology 2000;214:290–297.

52.Gelet A, Chapelon JY, Bouvier R, et al. [Preliminary results of the treatment of 44 patients with localized cancer of the prostate using transrectal focused ultrasound.] [French] Prog Urol 1998;8:68– 77.

53.Padhani AR, MacVicar AD, Gapinski CJ, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on prostatic morphology and vascular permeability evaluated with MR imaging. Radiology 2001;218:365–374.

54.Hugosson J, Aus G. Natural course of localized prostate cancer. A personal view with a review of published papers. [Review] Anticancer Res 1997;17: 1441–1448.

55.Tefilli MV, Gheiler EL, Tiguert R, et al. Role of radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer of high Gleason score. Prostate 1999;39:60–66.

56.Roberts SG, Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Zincke H. PSA doubling time as a predictor of clinical progression after biochemical failure following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:576–581.

57.Gripp S, Haller JC, Metz J, Willers R. Prostate-specific antigen: effect of pelvic irradiation. Radiology 2000; 215:757–760.

58.Leventis AK, Shariat SF, Slawin KM. Local recurrence after radical prostatectomy: correlation of US features with prostatic fossa biopsy findings. Radiology 2001; 219:432–439.

59.Sella T, Schwartz LH, Swindle PW, et al. Suspected local recurrence after radical prostatectomy: endorectal coil MR imaging. Radiology 2004;231:379–385.

60.Beyersdorff D, Taupitz M, Deger S, et al. [MRI of the prostate after combined radiotherapy (afterloading and percutaneous): histopathologic correlation.] [German] Rofo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Neuen Bildgeb Verfahr 2000;172:680–685.

61.Passomenos D, Dalamarinis C, Antonopoulos P, Sklavos H. Seminal vesicle hydatid cysts: CT features in two patients. AJR 2004;182:1089–1090.

62.Isotalo T, Tammela TL, Talja M, Valimaa T, Tormala P. A bioabsorbable self-expandable, self-reinforced poly-l-lactic acid urethral stent for recurrent urethral strictures: a preliminary report. J Urol 1998;160:2033– 2336.

63.Bertolotto M, de Stefani S, Martinoli C, Quaia E, Buttazzi L. Color Doppler appearance of penile cavernosal-spongiosal communications in patients with severe Peyronie’s disease. Eur Radiol 2002;12: 2525–2531.

64.Lebret T, Herve JM, Lugagne PM, et al. [Extra-corpo- real lithotripsy in the treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Use of a standard lithotriptor (Multiline Siemens) on “young” (less then 6 months old) plaques.] [Review] [French] Prog Urol 2000;10:65–70.

861

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

65.Naroda T, Yamanaka M, Matsushita K, et al. [Clinical studies for venogenic impotence with color Doppler ultrasonography—evaluation of resistance index of the cavernous artery.] [Japanese] Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1996;87:1231–1235.

66.Della Negra E, Martin M, Bernardini S, Bittard H. [Spermatic cord torsion in adults]. [French] Prog Urol 2000;10:265–270.

67.Sanelli PC, Burke BJ, Lee L. Color and spectral Doppler sonography of partial torsion of the spermatic cord. AJR 1999;172:49–51.

68.Baud C, Veyrac C, Couture A, Ferran JL. Spiral twist of the spermatic cord: a reliable sign of testicular torsion. Pediatr Radiol 1998;28:950–954.

69.Paltiel HJ, Connolly LP, Atala A, Paltiel AD, Zurakowski D, Treves ST. Acute scrotal symptoms in boys with an indeterminate clinical presentation: comparison of color Doppler sonography and scintigraphy. Radiology 1998;207:223–231.

70.Sebe P, Haab F, Nouri M, Tligui M, Gattegno B, Thibault

P.[Epididymal gaseous abscess after BCG treatment.] [French] Prog Urol 2000;10:99–100.

71.Callejas-Rubio JL, Ortego N, Diez A, Castro M, De La Higuera J. Recurrent epididymo-orchitis secondary to Behcet’s disease. J Urol 1998;160:496.

72.Aragona F, Pescatori E, Talenti E, Toma P, Malena S, Glazel GP. Painless scrotal masses in the pediatric population: prevalence and age distribution of different pathological conditions—a 10 year retrospective multicenter study. J Urol 1996;155:1424–1426.

73.Langer JE, Ramchandani P, Siegelman ES, Banner MP. Epidermoid cysts of the testicle: sonographic and MR imaging features. AJR 1999;173:1295–1299.

74.Sirpa A, Martti AO. Results of fibrin glue application therapy in testicular hydrocele. Eur Urol 1998;33:497– 499.

75.Mikata N, Imao S, Nakamura K, Tokieda K, Kawahara

Y.[The Leydig cell tumor and combined germ cell tumor in the unilateral testis. A case report.] [Japanese] Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1998;89: 507–510.

76.Bussar-Maatz R, Weissbach L. Retroperitoneal lymph node staging of testicular tumours. TNM Study Group. Br J Urol 1993;72:234–240.

77.Renshaw AA. Testicular calcifications: incidence, histology and proposed pathological criteria for testicular microlithiasis. J Urol 1998;160:1625– 1628.

78.Kole AC, Hoekstra HJ, Sleijfer DT, Nieweg OE, Schraffordt Koops H, Vaalburg W. L-(1-carbon- 11)tyrosine imaging of metastatic testicular nonseminoma germ-cell tumors. J Nucl Med 1998;39: 1027–1029.

79.Maszelin P, Lumbroso J, Theodore C, Foehrenbach H, Merlet P, Syrota A. [Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDO) positron emission tomography (PET) in testicular germ cell tumors in adults: preliminary French clinical evaluation, development of the technique and its clinical applications.] [French] Prog Urol 2000;10: 1190–1199.

80.Bach AM, Sheinfeld J, Hann LE. Abnormal testis at US in patients after orchiectomy for testicular neoplasm. Radiology 2000;215:432–436.

81.Bachaud JM, Berthier F, Soulie M, et al. [Risk of second non-germ cell cancer after treatment of stage I-II testicular seminoma.] [French] Prog Urol 1999;9:689– 695.

82.Hosten N, Stroszczynski C, Rick O, Lemke M, Felix R. [Retroperitoneal recurrence of non-seminomatous testicular tumors: computerized tomography findings before retroperitoneal lymph node excision.] [German] Rofo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Neuen Bildgeb Verfahr 1999;170:61–65.

83.Sogani PC, Perrotti M, Herr HW, Fair WR, Thaler HT, Bosl G. Clinical stage I testis cancer: long-term outcome of patients on surveillance. J Urol 1998;159: 855–858.

84.Ito K, Iigaya T, Umezawa A. [Case of testicular cancer with malignant transformation in the residual retroperitoneal mature teratoma 8 years after the initial chemotherapy.] [Japanese] Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1998;89:622–666.

85.Steyerberg EW, Keizer HJ, Sleijfer DT, et al. Retroperitoneal metastases in testicular cancer: role of CT measurements of residual masses in decision making for resection after chemotherapy. Radiology 2000;215: 437–444.

86.Ricci Z, Koenigsberg M, Whitney K. Sonography of an arteriovenous-type hemangioma of the testis. AJR 2000;174:1581–1582.

87.Delahunt B, Eble JN, King D, Bethwaite PB, Nacey JN, Thornton A. Immunohistochemical evidence for mesothelial origin of paratesticular adenomatoid tumour. Histopathology 2000;36:109–115.

88.Lachkar A, Sibert L, Gobet F, Thoumas D, Bugel H, Grise P. [Unusual tumor: liposarcoma of the spermatic cord.] [Review] [French] Prog Urol 2000;10:1228– 1231.

89.Cast JE, Nelson WM, Early AS, et al. Testicular microlithiasis: prevalence and tumor risk in a population referred for scrotal sonography. AJR 2000;175: 1703–1706.

90.Pieri S, Minucci S, Morucci M, Giuliani MS, De’Medici L. [Percutaneous treatment of varicocele. 13-year experience with the transbrachial approach.] [Italian] Radiol Med 2001;101:165–171.

91.Salerno S, Cannizzaro F, Lo Casto A, Romano P, Bentivegna E, Lagalla R. [Anastomosis between the left internal spermatic and splanchnic veins. Retrospective analysis of 305 patients.] [Italian] Radiol Med 2000;99: 347–351.

92.Kleinclauss F, Della Negra E, Martin M, Bernardini S, Bittard H. [Spontaneous thrombosis of left varicocele.] [French] Prog Urol 2001;11:95–96.

93.Morvay Z, Nagy E. The diagnosis and treatment of intratesticular varicocele. [Review] Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1998;21:76–78.

94.Belli L,Arrondello C,Antronaco R, Curzio D, Morosi E, Fugazzola C. [Venography of postoperative recurrence of symptomatic varicocele in males.] [Italian] Radiol Med 1998;95:470–473.

95.Ruibal M, Quintana JL, Fernandez G, Zungri E. Segmental testicular infarction. J Urol 2003;170:187–188.

96.Sentilhes L, Dunet F, Thoumas D, Khalaf A, Grise P, Pfister C. Segmental testicular infarction: diagnosis and strategy. Can J Urol 2002;9:1698–1701.