Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

842

Extratesticular Fluid

Bowel in an inguinal hernia can mimic the cystic structures outlined below. Bowel is identified with US by peristalsis. Some bowel in a hernia can often be reduced manually.

An epidermal scrotal inclusion cyst, cutaneous in location, is probably due to abnormal embryonal closure of the median raphe. These cysts range from cystic to mostly solid structures, most are hypoechoic but their echogenicity varies considerably.

Spermatocele

The seminiferous tubules merge and connect with tubuli recti, which then enter the mediastinum testis and form the rete testis. Efferent ductules from the rete testis form the head of the epididymis. Dilation of the efferent ductules within the epididymis is believed to result in spermatoceles and epididymal cysts. Spermatoceles are filled with thick, debris-laden fluid.

Ultrasonography reveals spermatoceles as unilocular or multilocular epididymal cysts. Debris within the spermatocele usually makes it hyperechoic. Uncommonly, a spermatocele has an appearance of a solid tumor. Sonographically spermatoceles, hydroceles, and epididymal cysts have a similar appearance. Their MRI appearance varies depending on fluid content.

Epididymal Cyst

Epididymal cysts are common; some are multiple and often are an incidental finding. Their etiology is unknown, but they appear to be congenital in nature. Some adolescents present with an uncomfortable scrotal tumor.

These serous fluid-filled cysts have a typical imaging appearance of an epididymal cyst as described above.

Symptomatic epididymal cysts and hydroceles are treated either surgically or with sclerotherapy. Multiple sclerotherapy treatments achieve a high success rate.

Hydrocele

Increased serous fluid in the tunica vaginalis sac represents a hydrocele. It is either congenital

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

and is detected early in life or develops later and manifests as painless scrotal swelling. The scrotum is most often involved, although occasionally a focal hydrocele develops in the spermatic cord.

The processus vaginalis is an inferior outpouching of the peritoneal cavity. Failure of the tunica vaginalis to close off from the peritoneal cavity results in communication between these two structures and fluid accumulates. Partial closure results in a cyst-like structure within the spermatic cord. Spermatic cord hydroceles present as firm inguinal tumors; US identifies a focal, anechoic, and avascular tumor superior to and separate from the testicle.

Abdominoscrotal hydroceles are rare; even rarer are bilateral ones. Most occur in the pediatric age group, enlarge rapidly, and tend to be quite large at initial presentation. Most congenital hydroceles in neonates resolve spontaneously and do not require imaging studies. If a hydrocele does not resolve and therapy is contemplated, imaging helps define the underlying anatomy and detects whether a hydrocele extends into the pelvis.

In a rare newborn a meconium-hydrocele results in an acute scrotum.

Most acquired hydroceles are idiopathic or related to trauma. Some are associated with an underlying disorder such as epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, torsion, or even a neoplasm. In particular, a small hydrocele should raise suspicion of an underlying neoplasm. Most are unilocular, although an occasional multilocular one is encountered. Calculi within hydroceles are not uncommon; US reveals hyperechoic, movable foci in the fluid. Multiple calcifications within a hydrocele should raise suspicion of tuberculosis.

Either US or MRI can be used to evaluate hydroceles, which tend to be mostly anechoic by US and provide an acoustic window for evaluating the underlying testis. Less common is a hyperechoic hydrocele, due to the presence of cholesterol crystals. Hydroceles are homogeneous and hypointense on T1and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, characteristic of fluid. Occasionally septations are identified within a hydrocele, although prominent septations should suggest a hematocele or pyocele.

A rare hydrocele becomes infected and is a surgical emergency.

843

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

After aspirating all fluid, some sclerotherapies have resulted in hydrocele disappearance. On the other hand, an attempt to treat testicular hydroceles by aspiration and injection of a two component fibrin glue consisting of fibrinogen and human thrombin led to hydrocele recurrences (74).

Hematocele

A hematocele consists of blood within a tunica vaginalis sac (i.e., a hydrocele with blood), while a hematoma is blood within the wall. Most hematoceles are traumatic in origin, with a minority due to neoplasm or a bleeding dyscrasia. Clinically, a hematocele presents as a firm, painful mass that does not transilluminate. An acute hematocele is often associated with testicular rupture. An occasional scrotal hematoma in neonates is associated with adrenal hemorrhage.

Initially US shows a hematocele to be mostly anechoic; with time it evolves into a hyperechoic structure and eventually develops a capsule, septations, and even calcifications; at this stage US of a hydrocele, pyocele, and hematocele reveals similar findings.

During the subacute phase, blood within a hematocele is hyperintense both on T1and T2weighted MRI.

Pyocele

A pyocele consists of pus in the tunica vaginalis, generally secondary to an epididymo-orchitis or rupture of a testicular abscess. A scrotal pyocele can be a sequela of bacterial peritonitis, presumably secondary to a peritoneal communication.

A hematocele and a pyocele have a similar initial US appearance, although an enlarged epididymis or testis is more common with a pyocele. Some pyoceles develop internal septa.

Cystocele

A scrotal cystocele is in the differential diagnosis of a fluid-filled scrotal structure. A cystocele should empty with voiding. At times US does not identify the actual connection between a cystocele and bladder.

Lymphocele

Representing an accumulation of lymph in a cystic structure, most scrotal lymphoceles (lymphocysts) develop after pelvic surgery. It can be difficult to differentiate a lymphocele from other cystic abnormalities.

A hydrocele, cystocele, and a lymphocele have similar US appearances, although the presence of septations suggests the latter. With a nondiagnostic fluid aspirate, a Tc-99m albumin colloid lymphogram may visualize pelvic lymphatic channels and eventual pooling of activity within a scrotal lymphocele.

Lymphangioma

A lymphangioma is a tumor of lymphatic channels, often greatly dilated, and lined by endothelial cells. A chronic painless scrotal swelling is the most common presentation. Lymphangiomas range from solid, cystic, to mixed multilocular ones and are a sequella of congenital lymphatic obstruction. Ultrasonography reveals a complex, septated cystic tumor with a normal testis and cord in most. Their US appearance is similar to a hematocele or a pyocele.At times US suggests multiple cystic tumors adjacent to the testis. Yet a correct preoperative diagnosis is difficult and the differential ranges from hernias to various scrotal cysts. Some lymphangiomas extend into the perineum, inguinal region, pelvis and retroperitoneum. They recur after incomplete excision.

Arteriovenous Malformation

A scrotal arteriovenous malformation is either congenital or traumatic in origin.

Doppler US of an arteriovenous malformation reveals a high-velocity waveform; it can thus be differentiated from a varicocele. Magnetic resonance imaging outlines the extent of the lesion and detects fast flow within the visualized vessels.

Testicular Tumors

Considerable variability exists in classifying testicular tumors. Most authors employ a histologic classification, and one such modified scheme is used here, although from an imaging viewpoint it is not ideal.

844

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy of young men. With adequate therapy a 5-year survival of over 90% is achieved. Cancer prevalence is considerably higher in the white population of America and Europe compared to Asia and Africa, and the prevalence is increasing in Western Europe. Testicular tumors are rare in related family members. Those who have had one testicular cancer are at a considerably higher lifetime risk of developing another testicular cancer, either synchronously or metachronously. An increased risk, including bilateral tumors, exists in a setting of cryptorchidism. Testicular carcinomas develop in a setting of known testicular microlithiasis (discussed later; see Calcifications).

Typically a testicular neoplasm first manifests as a painless unilateral nodule. In general, a solid intratesticular tumor is considered to be malignant until proven otherwise.

Most testicular neoplasms are treated by orchiectomy. In a solitary testis an organpreserving resection is often appropriate. The potential role of such therapy as transcutaneous high-intensity focused ultrasound as an alternate to organ-preserving surgery is not clear.

The rare gonadoblastoma contains elements of germ cells and stromal tissue. Most are limited to patients with intersex syndromes.

Germ Cell Tumors

Clinical

Over 90% of testicular neoplasms are of germ cell origin, and in adults almost half of all germ cell tumors are seminomatous in origin. Seminomatous tissue is also often present in mixed germ cell tumors. The prevalence of germ cell tumors is approximately 4 per 100,000. The main reason to differentiate germ cell neoplasms as seminomas and nonseminomas is that they are treated differently. Germ cell tumors are not common in the pediatric age group.

An association appears to exist between prior infection by Epstein-Barr virus and subsequent development of seminomas and embryonal carcinomas. Patients with Down syndrome are at a slightly increased risk for testicular cancer; presumably the multiorgan malformations found in trisomy 21 also affect gonads.

Although not common, testicular germ cell tumors do occur bilaterally and are either syn-

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

chronous or metachronous in origin. Men with a testicular cancer who have an atrophic contralateral testis and those presenting at age 30 years or younger are at increased risk for a second germ cell tumor in the contralateral testis.

An association exists between membranous glomerulonephritis and a seminoma, presumably representing a manifestation of paraneoplastic syndrome. Gynecomastia develops in a minority of males both with seminoma and nonseminoma and, in a young adult, should lead to a further workup.

Occasionally a testicular tumor first manifests through metastases, with the primary tumor not palpable, and initially the metastasis is believed to represent an extraperitoneal extragonadal germ cell tumor. Ultrasonography detects some of the underlying silent primary tumors, although a rare primary testicular tumor regresses to the point that only a scar remains. An occasional primary testicular site is detected only years later (called burned-out cancer). Testicular US reveals such a burned-out testicular tumor as a hyperechoic region. Some of these men have undergone chemotherapy, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, and an ipsilateral orchiectomy, with pathologic examination simply revealing a testicular scar; the hyperechoic focus seen with US probably represents the remains of such a burned-out neoplasm. The etiology of this phenomenon is unknown, although ischemic or immunologic factors are probably involved.

Complicating this issue is that not all germ cell tumors occur only in the testes. For instance, Klinefelter’s syndrome patients have an increased prevalence of extragonadal germ cell tumors.

Among more bizarre tumors were simultaneous germ cell and stromal tumors in the same testis in a 24-year-old man (75); the tumor contained seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and Leydig cell tumor components.

Doubling rate for many germ cell tumors is measured in days.

Detection

High-resolution US should detect most germ cell tumors. These tumors are mostly hypoechoic to normal testicular parenchyma. In general, although many hyperechoic testicular

845

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

tumors are benign, their US appearance alone cannot be used to exclude a malignancy. Most testicular neoplasms are hypervascular. Doppler US has played a limited role in evaluating these tumors.

A diagnosis of germ cell tumor is typically established by radical inguinal orchiectomy.

Staging

A number of staging systems are in use for seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, but the TNM staging system is common (Table 13.6). Most seminomas spread via lymphatics, while nonseminomatous teratomas and

Table 13.6. Tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging systems of testicular tumors

(Extent of primary tumor is classified after radical orchiectomy)

Primary tumor:

Tx |

Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 |

No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis |

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (carcinoma in |

|

situ) |

Tl |

Tumor limited to testis and epididymis |

|

without vascular/lymphatic invasion; tumor |

|

may invade into tunica albuginea but not |

|

tunica vaginalis |

T2 |

Tumor limited to testis and epididymis with |

|

vascular/lymphatic invasion, or tumor |

|

extending through tunica albuginea with |

|

involvement of tunica vaginalis |

T3 |

Tumor invades spermatic cord with or without |

|

vascular/lymphatic invasion |

T4 |

Tumor invades scrotum with or without |

|

vascular/lymphatic invasion |

Lymph nodes (clinical): |

|

Nx |

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 |

Metastasis with lymph node mass 2 cm or less |

|

in greatest dimension; or multiple lymph |

|

nodes, none more than 2 cm in greatest |

|

dimension |

N2 |

Metastasis with lymph node mass, more than |

|

2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest |

|

dimension; or multiple lymph nodes, any |

|

one mass greater than 2 cm but not more |

|

than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

N3 |

Metastasis with lymph node mass more than |

|

5 cm in greatest dimension |

Lymph nodes (pathologic): |

|

Nx |

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 |

Metastasis with lymph node mass 2 cm or less |

|

in greatest dimension and less than or |

|

equal to 5 nodes positive, none more than |

|

2 cm in greatest dimension |

N2 Metastasis with lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension; or more than 5 nodes positive, none more than 5 cm; or evidence of extranodal extension of tumor

N3 Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension

Distant metastasis: |

|

|

|

||

Mx |

Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

|

|||

M0 |

No distant metastasis |

|

|

||

M1a |

Nonregional nodal or pulmonary metastasis |

||||

M1b |

Distant metastasis other than to nonregional |

||||

|

|

lymph nodes and lungs |

|

|

|

Serum tumor markers: |

|

|

|

||

Sx |

Marker studies not available or not performed |

||||

S0 |

Marker study levels within normal limits |

|

|||

S1 |

LDH <1.5 ¥ N and hCG (mIU/mL) <5000 and |

||||

|

|

AFP (ng/mL) <1000 |

|

|

|

S2 |

LDH 1.5–10 ¥ N or hCG (mIU/mL) |

|

|||

|

|

5000–50,000 or AFP (ng/mL) 1000–10,000 |

|||

S3 |

LDH >10 ¥ N or hCG (mlu/mL) >50,000 or |

||||

|

|

AFP (ng/mL) >10,000 |

|

|

|

Tumor stages: |

|

|

|

||

Stage 0 |

|

Tis |

N0 |

M0 |

S0 |

Stage IA |

|

T1 |

N0 |

M0 |

S0 |

Stage IB |

|

T2 |

N0 |

M0 |

S0 |

|

|

T3 |

N0 |

M0 |

S0 |

|

|

T4 |

N0 |

M0 |

S0 |

Stage IC |

|

any T |

N0 |

M0 |

S1–3 |

Stage IIA |

any T |

N1 |

M0 |

S0 |

|

|

|

any T |

N1 |

M0 |

S1 |

Stage IIB |

|

any T |

N2 |

M0 |

S0 |

|

|

any T |

N2 |

M0 |

S1 |

Stage IIC |

|

any T |

N3 |

M0 |

S0 |

|

|

any T |

N3 |

M0 |

S1 |

Stage IIIA |

any T |

any N |

M1a |

S0 |

|

|

|

any T |

any N |

M1a |

S1 |

Stage IIIB |

any T |

N1–3 |

M0 |

S2 |

|

|

|

any T |

any N |

M1a |

S2 |

Stage IIIC |

any T |

N1–3 |

M0 |

S3 |

|

|

|

any T |

any N |

M1a |

S3 |

|

|

any T |

any N |

M1b |

any S |

Serum tumor maker abbreviations: AFP, a-fetoprotein; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; N, upper limit of normal for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay; mIU, milli International units.

Source: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition (2002), published by Springer-Verlag, New York, NY, used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, IL.

846

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

A B

Figure 13.8. Metastatic seminoma. A,B: Two CT images identify a large, poorly marginated intraabdominal tumor (arrows). Extensive peritoneal involvement, including ascites, was also evident. (Courtesy of Algidas Basevicius, M.D., Kaunas Medical University, Kaunas, Lithuania.)

choriocarcinomas more often spread primarily hematogenously. Thus lung metastases are more common with nonseminomas, but retroperitoneal, mediastinal, and neck involvement is more common with seminomas (Fig. 13.8).

Testicular lymphatics drain alongside the testicular arteries and veins into nodes close to the renal hila and eventually into para-aortic nodes. Left sentinel nodes are located close to the renal hilum; on the right these nodes are paracaval in location, inferior to the renal vessels. Tumors involving the epididymis drain into the iliac nodes. Right-sided tumors tend to spread more often to the left para-aortic nodes than vice versa. Drainage occurs to other sites, such as to inguinal and iliac nodes, if the usual lymphatic drainage pathways become obstructed.

With metastasis, left renal vein and inferior vena caval invasion are not uncommon and are detected by imaging (Fig. 13.9). An endovascular biopsy is diagnostic. These tumors can result in a life-threatening malignant pulmonary embolus.

The results of a prospective multicenter study of extraperitoneal lymph node involvement by testicular tumors are listed in Table 13.7. Although this study is now dated, it does provide relative sensitivities of various tests. Nodal involvement by tumor is not identified by CT directly; rather, enlarged lymph nodes in the

presence of known tumor suggest metastases. In general, as the diameter of a lymph node increases, the likelihood of metastasis increases almost continuously. Ultrasonography is not accurate in detecting extraperitoneal lymph node involvement.

When associated with germ cell tumors, laminar calcifications suggest extension beyond the tunica albuginea (77). An occasional “burned-out” germ cell tumor develops curvilinear calcifications, similar to those seen with a Sertoli cell tumor.

Currently chest and abdominopelvic CT are part of staging these tumors. A negative study, however, has limited significance. Imaging cannot differentiate reliably between stage I (tumor confined to testis) and stage II (spread to regional nodes), and thus retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is necessary.

Magnetic resonance imaging has a limited role in the staging of germ cell tumors. Tumor signal intensity is similar to that of normal tunica albuginea,and invasion cannot be readily determined. In evaluating extraperitoneal lymph node invasion, MRI is similar to CT; namely, lymph node size is used as the primary criterion.

Preliminary studies suggest that FDG-PET appears to have a role in staging metastatic testicular germ cell tumors by detecting increased carbohydrate metabolism of malig-

847

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

Figure 13.9. Metastatic testicular carcinoma. Inferior vena cavagram reveals a tumor thrombi in the inferior vena cava (arrows) and occlusion of the left common iliac vein. Retroperitoneal adenopathy and lung metastases were also present. (Courtesy of David Waldman, M.D., University of Rochester.)

nant cells. Both primary seminomas and malignant teratomas reveal avid uptake. Normal tissue uptake is found in differentiated teratomas and in necrotic tissue.

L-(1–11C)tyrosine PET imaging in men with retroperitoneal metastatic nonseminoma testicular germ cell tumors did not detect most tumors (78); in fact, even with large, inhomoge-

Table 13.7. Retroperitoneal lymph node involvement by testicular tumors*

|

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|

(%) |

(%) |

Bipedal lymphography |

71 |

60 |

Computed tomography |

41 |

94 |

Abdominal |

31 |

87 |

ultrasonography |

|

|

a-fetoprotein/human |

|

|

chorionic gonadotropin |

37 |

93 |

All modalities combined |

88 |

48 |

* Final diagnosis was based on histology of resected retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Source: Adapted from Bussar-Maatz and Weissbach (76).

neous tumors identified by CT, PET revealed decreased uptake at the site.

Lymphography has been used in the past to evaluate extraperitoneal lymph node involvement. With advances in CT, however, lymphography currently is rarely employed for this purpose; CT, especially multislice, provides additional information about tumor invasion.

Follow-Up

The current primary role of FDG-PET is in men with elevated serum tumor markers and no tumor identified by conventional imaging; keep in mind that FDG-PET is also positive in a setting of postoperative inflammation (79). False-negative studies also occur. The FDG-PET scans are more accurate than CT in detecting residual tumor when performed several weeks or later after chemotherapy.

In evaluating local recurrence after orchiectomy for testicular neoplasms, 67% of US-detected focal tumors and 27% of heterogeneous changes consisted of cancer (80).

Seminoma

Seminoma is the most common germ cell tumor. Histologically, most seminomas are solid tumors composed of sheets of uniform large tumor cells having an overall superimposed fibrous structure, with an anaplastic appearance found in a minority. Some contain a lymphocytic infiltrate. These tumors vary from a small nodule to diffuse infiltration and testicular enlargement. An occasional one is associated with testicular microlithiasis.

Peak incidence occurs in the fourth and fifth decades of life. It is rare under the age of 10 years and over the age of 60 years. A minority of patients have detectable tumor markers b- human chorionic gonadotropin (b-hCG), lactate dehydrogenase, and placental alkaline phosphatase. In most patients with a seminoma at least one of these three markers is elevated. Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase levels correlate with seminoma invasive status, metastatic status, and poor outcome, while serum b-hCG levels correlate only with metastatic status; most seminomas produce small amounts of hCG, and an elevated serum level reflects an increase in tumor volume and thus suggests metastases. Placental alkaline phosphatase has the highest

848

sensitivity for detecting metastatic disease. A pure seminoma does not result in elevated a- fetoprotein levels, and the presence of this tumor marker should suggest a nonseminomatous or mixed tumor.

Some of these tumors first manifest by their metastases. The anaplastic variety appears to be more aggressive than a more typical seminoma.

Ultrasonography reveals most seminomas as focal, solid, and well-circumscribed hypoechoic tumors. Most other germ cell tumors do not have a clearly defined tumor margin. A minority of seminomas contain hypoechoic regions. Cystic or hyperechoic regions are not seen and, if present, should suggest another diagnosis. Larger tumors tend to be hypervascular, a finding evident with Doppler US (Fig. 13.10).

Seminomas are isointense to normal tissue on T1and mostly hypointense and relatively homogeneous on T2-weighted MR images. They tend to be homogeneous, and regions of increased signal intensity presumably represent either bleeding or calcifications. They enhance less than normal testicular tissue.

Initial seminoma therapy is orchidectomy. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy for pos-

Figure 13.10. Testicular seminoma. Transverse Doppler image of the left testis. Note hypervascular hypoechoic mass (arrows) occupying most of the testis. Residular normal testicular tissue is present anteriorly (arrowhead). (Courtesy of Deborah Rubens MD, University of Rochester.)

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

torchidectomy relapse of stage I and IIA disease achieves long-term cure rates of 85% or more; relapse-free rates are predicted by tumor size, age, and small vessel invasion.

Seminoma patients require long-term posttherapy follow-up, including a search for radio- therapy-related secondary cancers years later. Thus a review of men treated at the Institut Claudius Regaud for stages I and II testicular seminoma found an overall second nongerm cell cancer in 11% (81); the Standardized Incidence Ratio was significantly increased in men treated with supraplus infradiaphragmatic radiation, but not in those treated with infradiaphragmatic radiation only. Also, the incidence of second cancers increased with the duration of follow-up.

Spermatocytic Seminoma

Whether a spermatocytic seminoma is a variant of a seminoma or a separate entity is debatable. Histologically, cells resemble maturing spermatogonia. This is a rare testicular neoplasm occurring only in adults and developing only in descended testes. The vast majority are benign, although an occasional one is associated with a testicular sarcoma.

Nonseminoma

In the United States, embryonal cell carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and choriocarcinoma are considered nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. British authors prefer to lump nonseminomatous germ cell tumors under malignant teratomas. A number of these tumors contain more than one cell type and these are known as mixed germ cell tumors. Histologically, nonseminomatous germ cell tumors have a heterogeneous appearance. They are prone to hemorrhage and necrosis. An elevated serum a-fetoprotein level should suggest a nonseminoma.

Magnetic resonance imaging reveals most of these tumors to be more heterogeneous than seminomas with all sequences. They contain regions of high and low signal intensity both with T1and T2-weighted images. Because of their MRI heterogeneity, most, but not all, of these tumors can be differentiated from seminomatous tumors.

849

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

Embryonal Cell Carcinoma: An embryonal cell carcinoma is a highly malignant undifferentiated tumor occurring either by itself or as part of a mixed germ cell tumor. A rare embryonal cell carcinoma undergoes differentiation to a peripheral neurectodermal tumor. These tumors occur after puberty, with a peak in young men. They invade readily. Metastases are common at the time of initial diagnosis. Embryonal cell carcinomas are associated with elevated a-fetoprotein levels and about half have elevated b-hCG levels.

Ultrasonography can reveal cysts, calcifications, or areas of hemorrhage. These tumors tend to be hypoechoic.

Yolk Sac Tumors: A yolk sac tumor, or endodermal sinus tumor, predominates in childhood, representing an embryonal adenocarcinoma of the prepubertal testis. It is the most common testicular neoplasm in infants. In adult men this tumor tends to be part of a mixed germ cell tumor. An occasional one occurs in other body parts. Most infants with a yolk sac tumor have elevated a-fetoprotein levels.

A yolk sac tumor occasionally is associated with testicular microlithiasis. The US appearance varies from heterogeneous to homogeneous. Some tumors contain cystic regions. This tumor is not as well marginated as a seminoma and tends to invade adjacent structures.

Teratoma: Primary testicular teratomas contain several germ cell layers and are classified into mature and immature types, with the latter (teratocarcinoma, teratosarcoma, or teratoma with malignant transformation) containing undifferentiated tissue from germ cell layers and having undergone malignant transformation.

Teratomas have two peak incidences: one in infancy and early childhood and another in young men. In the very young they tend to be mature and benign. About half of prepubertal boys with a testicular teratoma have an elevated a-fetoprotein level. Most postpubertal teratomas are malignant. Of interest is that any element in a teratoma can metastasize. A majority of malignant testicular teratomas present with metastatic disease. Occasionally a metastasis contains other subtypes of nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, such as a sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, or even a neuroectodermal tumor.

Pretherapy, most teratomas have an inhomogeneous appearance and contain both solid and

cystic components. A cystic region should not be confused with a benign cyst. Some contain calcifications; the presence of bone or cartilage indicates maturity. A capsule is seen as a hypointense band in the periphery. A PET scan suggests a malignant teratoma in presence of increased tumor uptake.

Choriocarcinoma: A choriocarcinoma is the least common testicular malignancy. Histologically, this tumor contains two cell types: syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts. Most choriocarcinomas are part of a mixed germ cell tumor. An occasional choriocarcinoma is extraperitoneal in origin.

This is a highly malignant tumor occurring mostly in the second and third decades of life. Metastasis is via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, and at times metastases manifest before a primary tumor is detected. These tumors are associated with elevated b-hCG levels produced by syncytiotrophoblasts; a- fetoprotein levels are not elevated in pure choriocarcinomas.

Hemorrhage and necrosis are common imaging findings.

Mixed Germ Cell Tumor: A mixed germ cell tumor contains several germ cell elements, with the most common combination being an embryonal cell carcinoma and teratoma elements (teratocarcinoma). The embryonal carcinomatous component often represents more than 50% of the tumor mass. These tumors often contain both solid and cystic components and have an overall inhomogeneous appearance.

A gonadoblastoma consists of a mixture of a germ cell tumor and a stromal tumor. Most occur in a setting of cryptorchidism and other congenital abnormalities.

Only about half of mixed germ cell tumors have a homogeneous appearance; many contain cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, or necrosis, and, as a result, the US appearance varies considerably. An imaging appearance of a necrotic tumor containing multilocular cysts is common.

An FDG-PET scan of retroperitoneal metastases often reveals heterogeneous, increased glucose metabolism prior to chemotherapy, reverting to normal FDG uptake after chemotherapy.

Therapy/Follow-Up of Nonseminomas:

Chemotherapy is curative in most individuals with nonseminomatous tumors.

850

Imaging studies generally do not play a major role in the follow-up of nonseminoma and mixed germ cell tumors because adequate serum markers are available (a-fetoprotein and b-hCG). Persistent elevation of tumor markers after orchidectomy suggests residual tumor. Although increased levels usually signify tumor progression, they are not specific to tumor type. Elevated a-fetoprotein levels occur with hepatocellular carcinomas, some gastrointestinal neoplasms, bronchial carcinomas, and some benign liver disorders, while b-hCG levels are elevated with some gastrointestinal, liver, pancreatic, and urogenital neoplasms. At times elevated b-hCG levels result in gynecomastia. Negative tumor marker levels are of less significance and are seen even with metastatic disease.

Imaging is useful after orchidectomy primarily to detect metastases. A tumor developing after chemotherapy is not necessarily a recurrence; some of these are mature teratomas. Computed tomography is often employed to detect residual tumor after chemotherapy of relapsing nonseminomatous testicular tumors. Among men treated by salvage chemotherapy, CT does not reliably differentiate tumor, scarring, and necrosis (82); CT does, however, provide guidance for lymphadenectomy, which is often considered.

Among men with clinical stage I (T1) nonseminomatous germ cell testicular tumors treated by orchiectomy alone, 74% remained disease-free when followed for a median of 11 years (83); relapses are mostly in those with predominantly embryonal carcinomas and tumors showing vascular invasion, and the authors suggest management by surveillance alone after orchiectomy in this select population with clinical stage I tumors, normal serum markers, and neither predominant embryonal carcinoma nor vascular invasion.

The growing teratoma syndrome is applied to nonseminoma testicular germ cell tumors, which, after chemotherapy, continue to enlarge in a setting of normal tumor markers. Residual tumor resection is associated with a good prognosis. Nevertheless, this issue is complex, illustrated by the following: An orchiectomy in a 21-year-old man with a left testicular tumor and extraperitoneal lymph node metastases revealed a mixed germ cell tumor containing immature teratoma, embryonal carcinoma, and

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

seminoma components (84); after chemotherapy, a-fetoprotein levels declined, but over the next 8 years he underwent several paraaortic tumor resections for enlarged nodes, with the last one yielding adenocarcinoma within parts of a mature teratoma. The authors concluded that the malignant potential of these tumors cannot be evaluated from its maturation and any residual tumor should be resected.

Among extraperitoneal tumors detected by CT after chemotherapy for nonseminomatous testicular cancers, at resection 47% consisted of benign tissue and 53% were either mature teratomas or residual cancer (85); a small residual tumor size and reduction in size after chemotherapy are predictors of benign histology.

An occasional man successfully treated for a nonseminomatous germ cell tumor develops lymphoma years later.

Sex Cord and Stromal Tumors

The nongerm cell tumors include Leydig cell tumor, Sertoli cell tumor, and granulosa cell tumor. Most are benign. Combinations of several of these tumors also occur; these are simply called stromal tumors. Hormone secretion is common.

Leydig Cell Tumors.

Stromal (interstitial) Leydig cells produce androgen necessary for spermatogenesis. A Leydig cell tumor is the most common stromal tumor. It is a tumor of adults, with only a minority developing prepuberty. In the elderly these tumors tend toward malignancy, with the more malignant ones becoming hemorrhagic and necrotic. In some adults, only metastasis establishes their malignant nature.

A common presentation is a painless tumor or testicular enlargement. Some young boys develop precocious puberty, while young men tend towards gynecomastia and infertility. Serum testosterone levels are normal or low. An occasional malignant Leydig cell tumor is associated with high progesterone levels. A Leydig cell tumor can develop in a cryptorchid testis.

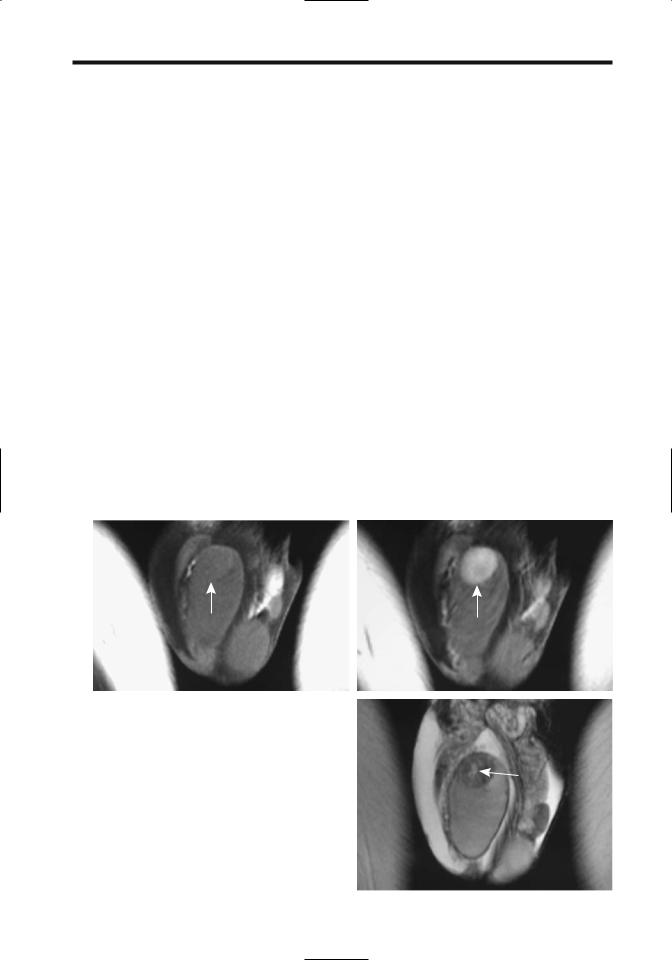

Leydig cell tumors are well marginated, encapsulated, solid, and relatively homoge-

851

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

neous, although some larger ones develop cysts and necrosis. Most are similar in appearance to germ cell tumors. Ultrasonography findings vary and range from hypoto hyperechoic. They tend to be isointense on T1and hypointense on T2-weighted images, an appearance similar to germ cell tumors (Fig. 13.11). Some malignant Leydig cell tumors have foci of increased signal intensity both on T1and T2-weighted images, thus mimicking nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

Sertoli Cell Tumors

Sertoli cells line the tubule basement membrane. Most Sertoli cell tumors are benign. Their prevalence is increased in tuberous sclerosis and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Some of these tumors calcify and some are bilateral.

One variant is a large-cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumor found mostly in boys. Usually benign, it has distinctive microscopic features and contains multifocal and curvilinear calcifications identifiable by imaging. This tumor is one of the components in Carney’s

complex (which includes cardiac and skin myxomas, myxoid mammary fibroadenomas, skin pigmentation, adrenocortical abnormalities, pituitary adenoma, and testicular tumors such as large-cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumor).

Granulosa Cell Tumor

Granulosa cell and theca tumors are rare in males. Two peaks occur: one during the first month of life and the other one in late adulthood. Their imaging appearance is similar to that of other stromal tumors.

Carcinoid

A primary testicular carcinoid is exceedingly rare. Carcinoid metastases to testes are more common.

Metastatic to Testes

Metastatic spread to the scrotum is by spermatic cord, lymphatics, or, least often, via a hematoge-

A B

Figure 13.11. Testicular Leydig cell tumor. Precontrast (A) and contrast-enhanced (B) T1-weighted MR images reveal marked tumor contrast enhancement (arrows). C: The tumor is hypointense on T2-weighted images. A central scar is evident (arrow). (Source: Fernández GC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging

in the diagnosis of testicular Leydig cell tumour. Br J Radiol |

|

2004;77:521–524, with permission from the British Institute of |

|

Radiology.) |

C |