Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

907

PERITONEUM, MESENTERY, AND EXTRAPERITONEAL SOFT TISSUES

Table 14.4. Computed tomography differentiation of tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcinomatosis

|

Tuberculous peritonitis |

|

Peritoneal carcinomatosis |

|

Reference |

(62) |

(63) |

(62) |

(63) |

|

|

|

|

|

Number of patients |

42 |

19 |

93 |

19 |

Peritoneal thickening |

|

|

|

|

Slight, smooth |

|

79% |

|

26% |

Irregular |

|

0% |

|

47% |

Peritoneal nodules |

|

0% |

|

37% |

Mesenteric nodules |

|

26% |

|

16% |

<5 mm in diameter |

52% |

|

52% |

|

≥5 mm |

52% |

|

12% |

|

Omental cakes |

8% |

21% |

20% |

37% |

Splenomegaly |

93% |

|

50% |

|

Ascites |

64% |

100% |

84% |

100% |

|

|

|

|

|

toneum. In general, a malignant mesenchymal |

a sarcoma. Two types of mesothelioma exist: the |

|||

neoplasm is more common than its benign |

more common malignant variety and a less |

|||

counterpart. Some poorly differentiated sarco- |

common relatively benign form. Whether these |

|||

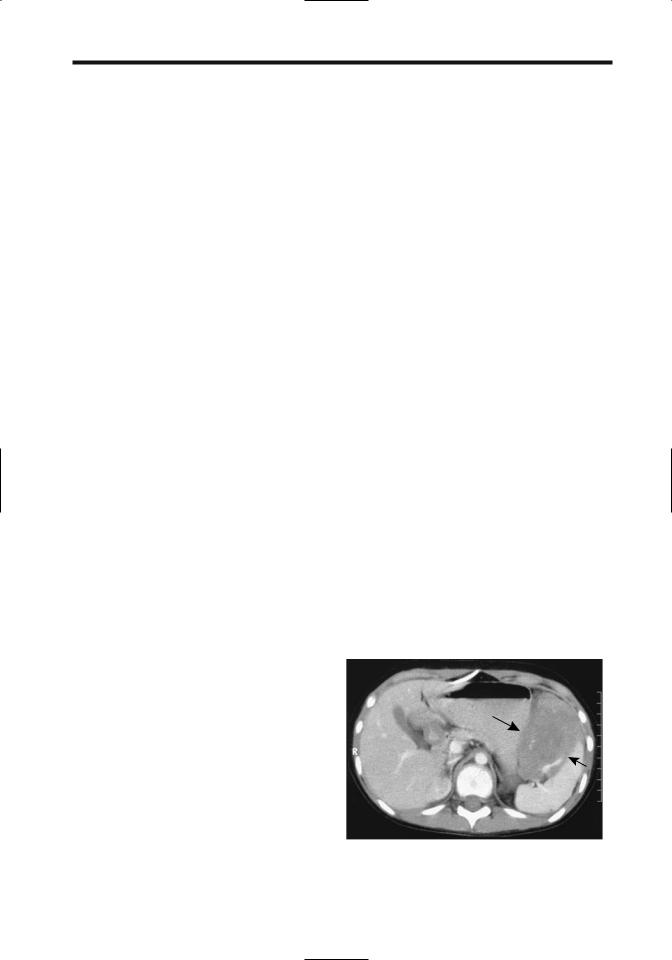

mas are difficult to classify (Fig. 14.18). The rare |

represent a variation of the same entity or are |

|||

peritoneal adenosarcoma probably originates |

different conditions is conjecture. One hypoth- |

|||

from regions of endometriosis. |

esis is that the benign variety simply represents |

|||

Both malignant and benign fibrous tumors |

a proliferation of mesothelioma cells due to a |

|||

develop in the retroperitoneum and peritoneal |

reaction to an insult. In either case, even the |

|||

cavity. Diffuse fibrosis/desmoid tumors have |

benign mesotheliomas tend to recur unless |

|||

been discussed earlier. |

completely resected. |

|||

|

|

|

Both the benign and malignant forms have |

|

Mesothelioma |

similar imaging findings, although some benign |

|||

peritoneal mesotheliomas have a multicystic |

||||

|

|

|

||

A number of authors list mesothelioma as a sep- |

imaging appearance and thus mimic other |

|||

arate type of neoplasm, although it is of mes- |

cystic tumors. These tumors range from small |

|||

enchymal origin, and the most common form is |

peritoneal nodules,large tumors,to diffuse peri- |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

A B

Figure 14.18. Poorly differentiated mesenteric sarcoma. A,B: Two CT images show a homogeneous midabdominal tumor (arrows) displacing contrast-filled small bowel loops. (Courtesy of Algidas Basevicius, M.D., Kaunas Medical University, Kaunas, Lithuania.)

B

B B

B