- •Foreword

- •Criminology Comes of Age

- •Rules That Commute

- •Environmental Criminology and the Path to Crime Control

- •Preface

- •The Author

- •Acknowledgments

- •Dedication

- •Table of Contents

- •List of Tables

- •List of Figures

- •Quotation

- •2.1 Serial Murder

- •2.1.1.1 Characteristics

- •2.1.2 Incidence, Population, and Growth

- •2.1.3 Theories

- •2.1.4 Victimology

- •2.2 Child Murder

- •2.3 Murder and Distance

- •3.1 Serial Rape

- •3.2 Serial Arson

- •4.2 Police Strategies

- •4.2.1 Linkage Analysis

- •4.2.1.1 Physical Evidence

- •4.2.1.2 Offender Description

- •4.2.1.3 Crime Scene Behaviour

- •4.2.2 Other Investigative Tactics

- •5.2 Organized and Disorganized Crime Scenes

- •5.4 Critiques

- •5.5 Evaluation Studies

- •5.7 Expert Testimony

- •6.1 Movement and Distance

- •6.2 Mental Maps

- •6.3 Awareness and Activity Spaces

- •6.3.1 Anchor Points

- •6.4 Centrography

- •6.5 Nearest Neighbour Analysis

- •7.1 Geography and Crime Studies

- •7.2 Environmental Criminology

- •7.2.1 Routine Activity Theory

- •7.2.2 Rational Choice Theory

- •7.2.3 Crime Pattern Theory

- •8.1 Target Patterns

- •8.1.1 Place and Space

- •8.1.2 Hunting Grounds

- •8.1.3 Target Backcloth

- •8.1.4 Crime Sites

- •8.1.5 Body Disposal

- •8.1.6 Learning and Displacement

- •8.1.7 Offender Type

- •8.2 Hunting Methods

- •8.2.1 Target Cues

- •8.2.2 Hunting Humans

- •8.2.3 Search and Attack

- •8.2.4 Predator Hunting Typology

- •9.1 Spatial Typologies

- •9.2 Geography of Serial Murder

- •9.2.1 Methodology

- •9.2.1.1 Serial Killer Data

- •9.2.1.2 Newspaper Sources

- •9.2.1.3 Offender, Victim, and Location Data

- •9.2.2 Serial Killer Characteristics

- •9.2.2.1 State Comparisons

- •9.2.3 Case Descriptions

- •9.2.3.1 Richard Chase

- •9.2.3.2 Albert DeSalvo

- •9.2.3.3 Clifford Olson

- •9.2.3.4 Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi

- •9.2.3.5 Peter Sutcliffe

- •9.2.3.6 Richard Ramirez

- •9.2.3.7 David Berkowitz

- •9.2.3.8 Jeffrey Dahmer

- •9.2.3.9 Joel Rifkin

- •9.2.3.10 John Collins

- •9.2.3.11 Aileen Wuornos

- •9.2.3.12 Ian Brady and Myra Hindley

- •9.2.3.13 Jerry Brudos

- •9.4 Serial Murder Characteristics

- •9.4.1 Offenders

- •9.4.2 Victims

- •9.4.3 Locations

- •9.4.4 Crime Parsing

- •9.4.5 Clusters

- •9.4.6 Trip Distance Increase

- •10.1 Mapping and Crime Analysis

- •10.2 Geography and Crime Investigation

- •10.3 Offender Residence Prediction

- •10.3.1 Criminal Geographic Targeting

- •10.3.2 Performance

- •10.3.3 Validity, Reliability, and Utility

- •10.3.3.1 Validity

- •10.3.3.2 Reliability

- •10.3.3.3 Utility

- •10.4.2 Operational Procedures

- •10.4.2.1 Information Requirements

- •10.4.3 Understudy Training Program

- •10.4.4 The Rigel Computer System

- •11.1 Strategies and Tactics

- •11.1.1 Suspect Prioritization

- •11.1.2 Police Information Systems

- •11.1.3 Task Force Management

- •11.1.4 Sex Offender Registries

- •11.1.5 Government and Business Databases

- •11.1.6 Motor Vehicle Registrations

- •11.1.7 Patrol Saturation and Stakeouts

- •11.1.8 Response Plans

- •11.1.9 Mail Outs

- •11.1.10 Neighbourhood Canvasses

- •11.1.11 News Media

- •11.1.12 Bloodings

- •11.1.13 Peak-of-Tension Polygraphy

- •11.1.14 Fugitive Location

- •11.1.15 Missing Bodies

- •11.1.16 Trial Court Expert Evidence

- •11.2 Jack the Ripper

- •DATA CODING FORM #1: SERIAL MURDER OFFENDERS

- •DATA CODING FORM #2: SERIAL MURDER VICTIMS

- •DATA CODING FORM #3: SERIAL MURDER LOCATIONS

- •Glossary

- •Bibliography

In order to remain unapprehended, the perpetrator of an execution-style murder such as I have planned must take precautions. One must think out well in advance a crime of this nature, in order for it to work.

We will need an isolated area, accessible by a short hike, away from any police patrols or parking lovers. The execution site must be carefully arranged for a speedy execution, once the victim has arrived... A grave must be prepared in advance away from the place of execution. (King, 1996, p. 219)

Rational choice and routine activity theory together provide powerful tools for understanding predatory criminal behaviour. In Felson’s view, “rational choice theory deals mainly with the content of decisions; routine activity approaches, in contrast, are seen to deal with the ecological contexts that supply the range of options from which choices are made” (Cornish & Clarke, 1986a, p. 10; see also Clarke & Felson, 1993a, 1993b; Felson, 1986). This is a useful convergence, and pattern theory, situational crime prevention, and problem-oriented policing (POP) all draw from their juxtaposition. Offender foraging space is determined by routine activities and rational choice (Canter & Hodge, 1997), and the perspectives have much to offer for both the theoretical and practical components of geographic profiling.

7.2.3Crime Pattern Theory

As chaotic as crime appears to be, there is often a rationality influencing the geography of its occurrence and some semblance of structure underlying its spatial distribution. Using an environmental criminology perspective, Brantingham and Brantingham (1981, 1984) present a series of propositions that provide insight to the processes underlying the geometry of crime. Their model of offence site selection, called crime pattern theory, suggests that criminal acts are most likely to occur in areas where the awareness space of the offender intersects with perceived suitable targets (i.e., desirable targets with an acceptable risk level attached to them).

These ideas suggest that most offenders do not choose their crime sites randomly. While any given victim may be selected by chance, the process of such random selection is spatially structured whether the offender realizes it or not. The psychological profile prepared by the FBI in the case of the Atlanta Child Murders proposed the following:

Your offender is familiar with the crime-scene areas he is in, or has resided in this area. In addition, his past or present occupation caused him to drive through these areas on different occasions ... the sites of the deceased are not random or “chance” disposal areas. He realizes these areas are remote and not frequently traveled by others. (Linedecker, 1991, p. 70)

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

After the arrest of Wayne Williams, police were able to determine that he had, in the past, done freelance photography assignments near several of the victim’s burial sites. “Very few criminals appear to blaze trails into new, unknown territories or situations in search of criminal opportunities” (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1998, p. 4). This spatial selection process is consistent with the routine activity approach with its emphasis on the relevance of regular and routine victim behaviours for an understanding of crime patterns (Clarke & Felson, 1993a). Ford (1990) stresses the investigative importance of identifying “routine victim activities and expected behaviors related to contact with and risk of victimization by a serial predator” (p. 116).

Crime pattern theory combines rational choice, routine activity theory, and environmental principles to explain the distribution of crimes. Target choice is affected by the interactions of offenders with their physical and social environments (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993b). Potential victims are not considered in isolation from their surrounding environment; the entire “target situation” must be seen as acceptable by the offender before a crime will occur (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993b).

“Pattern is a term used to describe recognizable interconnectiveness [physical or conceptual] of objects, processes, or ideas” (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993b, p. 264). This is a multidisciplinary approach that explores patterns of crime and criminal behaviour through an analysis of the processes associated with crime, site, situation, activity space, templates, triggering events, and motivational potential.

“Each criminal event is an opportune cross-product of law, offender motivation, and target characteristic arrayed on an environmental backcloth at a particular point in space-time. Each element in the criminal event has some historical trajectory shaped by past experience and future intention, by the routine activities and rhythms of life, and by the constraints of the environment” (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993b, p. 259). Environment in this context involves sociocultural, economic, institutional, and physical structures, at micro, meso, and macrolevels.

Brantingham and Brantingham used the concepts of opportunity, motivation, mobility, and perception in the development of their model of crime site geography. The model is based upon the following propositions:

(1)Individuals exist who are motivated to commit specific offenses.

(a)The sources of motivation are diverse. Different etiological models or theories may appropriately be invoked to explain the motivation of different individuals or groups.

(b)The strength of such motivation varies.

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

(c)The character of such motivation varies from affective to instrumental.

(2)Given the motivation of an individual to commit an offense, the actual commission of an offense is the end result of a multistaged decision process which seeks out and identifies, within the general environment, a target or victim positioned in time and space.

(a)In the case of high affect motivation, the decision process will probably involve a minimal number of stages.

(b)In the case of high instrumental motivation, the decision process locating a target or victim may include many stages and much careful searching.

(3)The environment emits many signals, or cues, about its physical, spatial, cultural, legal, and psychological characteristics.

(a)These cues can vary from generalized to detailed.

(4)An individual who is motivated to commit a crime uses cues (either learned through experience or learned through social transmission) from the environment to locate and identify targets or victims.

(5)As experiential knowledge grows, an individual who is motivated to commit a crime learns which individual cues, clusters of cues, and sequences of cues are associated with “good” victims or targets. These cues, cue clusters, and cue sequences can be considered a template which is used in victim or target selection. Potential victims or targets are compared to the template and either rejected or accepted depending on the congruence.

(a)The process of template construction and the search process may be consciously conducted, or these processes may occur in an unconscious, cybernetic fashion so that the individual cannot articulate how they are done.

(6)Once the template is established, it becomes relatively fixed and influences future search behavior, thereby becoming self-reinforcing.

(7)Because of the multiplicity of targets and victims, many potential crime selection templates could be constructed. However, because the spatial and temporal distribution of offenders, targets, and victims is not regular, but clustered or patterned, and because human environmental perception has some universal properties, individual templates have similarities which can be identified. (1981, pp. 28–29).

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

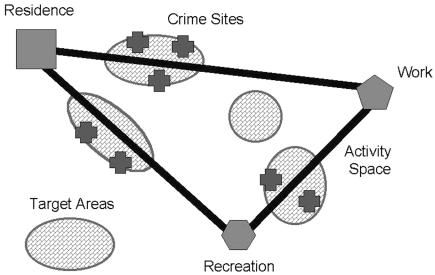

Figure 7.2 Crime site search geography.

Targets are selected from an offender’s awareness space and assessed against the criteria of suitability (gain or profit) and risk (probability of being observed or apprehended). These targets are scanned for certain cues (visibility, unusualness, symbolism) that are evaluated in terms of fit to the individual’s template. From the perspective of the offender, rational choices are then made and specific targets chosen for victimization. Such a selectionprocess is consistent with the concept of an offender operating within his or her “comfort zone” (Keppel, 1989).

A person’s awareness space forms part of his or her mental map and is constructed primarily, but not exclusively, from the spatial experiences of the individual. An awareness space is derived from, amongst other sources, an activity space, the latter being composed of various activity sites (residence, workplace, social activity locations, etc.) and the connecting network of travel and commuting routes. Well-known locations (landmarks, tourist sites, important buildings) may also become part of a person’s awareness space without actually being a component of their activity space.

Brantingham and Brantingham propose a dynamic process of target selection, with crimes occurring in those areas where suitable targets overlap the offender’s awareness space (Figure 7.2). Offenders then search outward from these areas, the search behaviour following some form of distance-decay function (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981, 1984; Rhodes & Conly, 1981). Search pattern probabilities can be modeled by a Pareto function, starting from the sites and routes that compose the activity space and then decreasing as distance away from the activity space increases. The Pareto function,

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

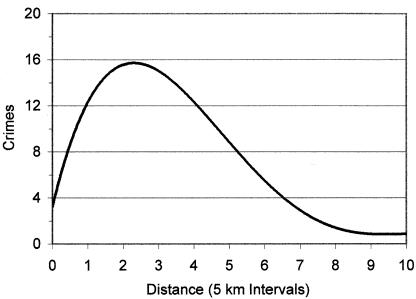

Figure 7.3 Distance-decay function.

named after the Italian economist, is suitable for fitting data that have a disproportionate number of cases close to the origin, making it appropriate for modeling distance-decay processes (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984). It takes the general form: y = k/xb.

There is usually a “buffer zone,” however, centred around the criminal’s residence, comparable to what Newton and Swoope (1987) call the coal-sack. effect. Within this zone, targets are viewed as less desirable because of the perceived level of risk associated with operating too close to home. For the offender, this area represents an optimized balance between the maximization of opportunity and the minimization of risk. The buffer zone is most applicable to predatory crimes; for affective-motivated offences it takes on less importance, as can be seen by the fact that domestic homicides usually occur within the residence. Figure 7.3 shows an example, derived from a serial rape case, 38of a typical buffered distance-decay function. The radius of the buffer zone is equivalent to the modal crime trip distance.

When Canter and Larkin (1993) regressed maximum distance from crime site to home against maximum distance between crime sites for a group of serial rapists in England, they found a regression equation constant equivalent to 0.98 kilometres (see Equation 6.5, above). This was the “safety zone”

38 Figure 7.3 displays the fourth-order polynomial trend line fitted (R2 = 0.730) to 79 crime trip distances for John Horace Oughton, the Vancouver Paperbag Rapist (Alston, 1994; see also Eastham, 1989).

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

within which sexual offenders are less likely to strike. Employing a similar analysis, Canter and Hodge (1997) found such zones for both U.S. and British serial killers (3.44 km and 0.53 km, respectively). But the idea of a “safety” is misleading, and some studies have misinterpreted the buffer zone as representing an area of no criminal activity. This is incorrect; a decrease in probability is not the same as zero probability. Much depends on whether an offender believes he or she can get away with the crime. Under the right circumstances, rapists have been known to attack women who live in their same apartment building.

There may be another explanation for the existence of the buffer zone. As the distance from an offender’s residence increases, so do the number of potential targets. The increase in criminal opportunity is linear; for example, there are twice as many possible targets at a distance of two kilometres than there are at one kilometre from an offender’s home. More generally, the target ratio between two distances is:

|

t2/t1 = d2/ d1 |

(7.1) |

where: |

|

|

t2 |

is the number of potential targets at d2; |

|

t1 |

is the number of potential targets at d1; |

|

d2 is the second distance; and d1 is the first distance.

Combining the linear increase in opportunity with the exponential decrease in travel inclination creates a buffered distance-decay function. This process is equivalent to a spiral search that may be a more accurate means of describing what offenders really do. The search may be physical, or it may be mental as various possible targets are considered and assessed (see Wright & Decker, 1996). Modeling this process produces theoretical distributions that closely match empirical ones. Mean and modal journey-to-crime distances can be varied through a parameter describing the probability of target selection. Greater distances result from either specific limited targets or discerning offenders (i.e., lower target selection probabilities). This may explain many of the empirical results found in the journey-to-crime literature.

The journey-to-crime function, comprised of least effort, spiral searches, and detection avoidance, could be the result of something known as the principle of least action. First suggested in 1744 by Pierre-Louis Maupertuis, a Berlin scientist, and later developed by the famous French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, least action refers to the minimization of quantities within dynamic systems (e.g., energy, distance, time, change, effort, cost, etc.). Most aspects of nature seem to follow the rule of economy suggested by the least action principle. It appears in theoretical physics, linguistics,

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC

finance, and many other areas (Casti, 1998). Apparently, the world is lazy. Refracted light bends at angles that create a path of minimal travel time. Word frequency studies show languages attempt to communicate as much information as possible in the fewest number of symbols. The coding regions in DNA molecules appear to do the same, and least action governs human movement patterns.

Studies of trail systems, for example, show that people do not just follow the shortest path. Instead, they do something more complicated by minimizing their discomfort. Existing routes may not be the most direct but creating new paths takes effort, so walkers compromise between convenience and distance. Trail growth (caused by people walking) and decay (brought on by weather and overgrowth) has been shown to follow processes of natural competition and selection (Casti, 1998).

© 2000 by CRC Press LLC