Лекции_Микроэкономика

.pdf

A.Friedman |

ICEF-2012 |

$ |

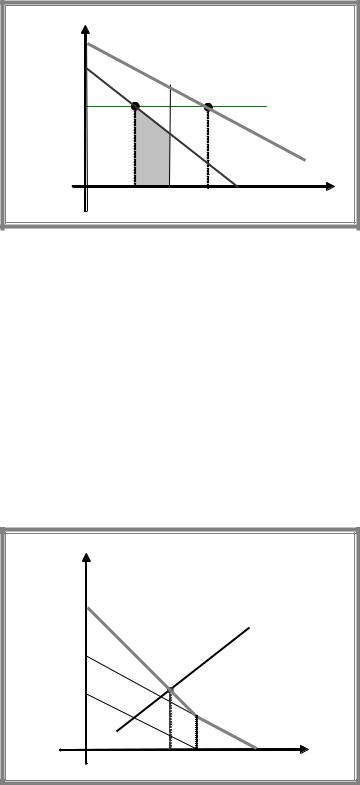

TAC reg TAC tax D F 0 |

t

F |

D |

MAC A |

|

MAC B |

|||

|

|

||

etaxA eregA |

eregB etaxB |

emission |

10.3 Public goods

Public good represents a special type of positive externality in consumption.

A good is called public good if it is non-rival in consumption, i.e. consumption by any one person does not reduce the amount available for others. Examples: national defence, TV broadcasting, roads.

Public goods may be non-excludable (if it is very costly to exclude non-payers from consumption of the good) or excludable. Non-excludable god is called pure public good.

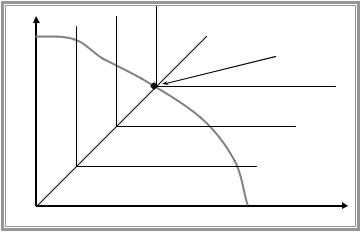

Consider an economy with two agents (A and B) and two consumption goods. Let X be public good and Y -private, then efficiency in output mix condition is given by

MRS XYA MRS XYB MRTXY

Graphically.

P,MC

PA ( Q ) PB |

( Q ) |

MC |

|

|

PB ( Q )

PA ( Q )

Qeff |

Q |

|

Free rider problem.

Suppose we have 2 roommates (A and B) that want to buy a TV. If each agent makes a contribution then they can purchase a large one and each agent’s valuation of a large TV equals 20. If only one contributes, then small TV can be purchased and each one can use it.

Each agent’s valuation of small TV is 10. Suppose that contribution equals 15.

121

A.Friedman |

|

|

ICEF-2012 |

|

Agent B |

||

|

Free ride |

Contribute |

|

Agent A Free ride |

0, 0 |

10, -5 |

|

Contribute |

-5, 10 |

5, 5 |

|

As 0>-5 and 10>5 free ride is a dominant strategy for each agent. As a result nobody contributes and no TV is purchased. Outcome is inefficient as, by contributing, both would be better off.

Solution of free-rider problem

If each agent could be charged a price equal to his marginal willingness to pay for the public good, a price system would bring an efficient outcome.

BUT (i) it is not always easy to exclude non-payers. This solution works with excludable public goods only.

(ii)Price discrimination is required. If price discrimination is not perfect, then additional loss may take place.

(iii)Perfect price discrimination requires information on individual marginal willingness to pay but agents with high valuation do not have an incentive to reveal their true valuation.

If public good is non-excludable it could be supplied by self-interested individuals for their own benefit but the amount supplied would be less than Pareto optimal one.

10.4 Public choice

Equity

Not every PO allocation could be desirable for society. For example the allocation, in which one person consumes everything and the other nothing is PO.

If we want to choose some particular PO allocation we have to make interpersonal comparisons of utility, which requires the introduction of value judgments. To do so we will introduce the social welfare function, which shows how the wellbeing of society depends

upon the utilities of its members SWF W u A ,u B . Allocation is said to be “fair” if it maximizes the SWF.

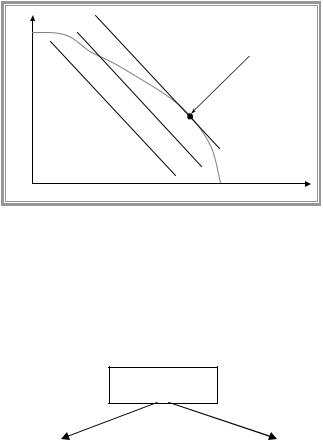

Let us illustrate all PO allocations in terms of utilities attained by agents by drawing utility possibilities frontier.

uB Society choice under Rawlsian

SWF

Utility possibilities frontier

0 |

u A |

122

A.Friedman |

ICEF-2012 |

Two examples of SWF would be analyzed:

Utilitarian SWF W u A ,u B u A u B ,

Rawlsian (or maximin) W u A ,u B min u A ,u B .

uB

0

Society choice under utilitarian SWF

Utility possibilities frontier

u A

Social choice and Arrow impossibility theorem

Note: this section was added in the syllabus (see UOL subject guide)

Preferences, voting and decisions

Government decisions are made by people. In democracies voting procedures are used to translate individuals’ preferences into collective decisions.

Voting rules

Unanimity voting |

|

Majority voting |

|

|

|

Under unanimity voting no proposal is approved unless every person votes for it.

The advantage of a unanimity rule is that it guarantees a pareto improvement. But it might be inefficient as each agent has an incentive to demand bribes to pass a public project.

With a majority voting rule one more than half of the voters must favor a measure for it to be approved.

Majority rule is less costly than unanimity voting. But (1) it does not necessarily lead to pareto improvement and (2) equilibrium may fail to exist due to voting paradox.

Example of voting (Condorset) paradox.

Consider an economy with three agents that face three choices over the size of a public project: small (S), medium (M) and large (L). Each agent has complete and transitive preferences so that he can compare any two projects and rank them. The corresponding ranking is presented in a table (from best to worst).

A |

B |

C |

S |

L |

M |

M |

S |

L |

L |

M |

S |

In pairwise majority voting S is preferred to M, M is preferred to L and L is preferred to S, i.e. social preferences are intransitive, which implies that there is no agreed ranking.

123

A.Friedman |

ICEF-2012 |

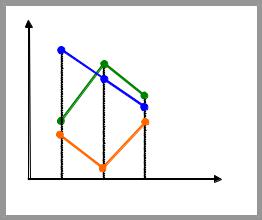

Of course the voting paradox does not take place in any situation. It depends on the structure of individual’s preferences. To illustrate the point we should sketch the corresponding utility functions.

u |

|

|

|

u A |

|

|

|

|

|

u C |

|

|

|

u B |

|

0 |

|

|

Quantity of |

S |

M |

L |

|

|

|

|

public good |

Preferences of agents A and C are single-peaked, i.e. the most preferred outcome exists and when we move from this outcome in any direction utility consistently falls. But preferences of agent B are not. In general when all voters’ preferences are single-peaked the voting paradox does not exist.

Define the median voter as the voter whose preferences lie in the middle of the set of all voter’s preferences in such a way that half the voters want more of the good than the median voter and half want less.

Median voter theorem

As long as all voters have single-peaked preferences and different issues are not packed together the outcome of majority voting reflects the preferences of the median voter.

Interest group politics

It is costly for voters to collect information on the issues they have to vote on. It is reasonable to suppose that voters will allocate time efficiently. As a result they would be better informed about those aspects of policy which are likely to have a big effect on them and will pay less attention to analyzing other policies. Moreover voters may work hard to influence legislation that promises to yield them large benefits or threatens to impose large cost upon them. Thus voters have an incentive to create special interest groups that may be motivated by a desire to obtain or keep economic rent (so called rent-seeking).

124