- •Уо «белорусский государственный экономический университет»

- •Contents

- •Lecture 1 geography and cultural regions of the u.S.A.

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 1. From the 16th century to the american revolution

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 2. From the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 3. The u.S. In the 20th and 21st centuries

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 3 federal government of the united states

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 4 u.S. Economy and demographics

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 5 the united states - nation of immigrants

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lectures 8 the united states culture and american identity

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 9 american cultural traits

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 10 american english

- •A). American Indian languages and their influence

- •1. British English vs. American English

- •When speaking about lexico-semantic differences one should pay attention to structural variants of words in be and ae. They differ in affixes while lexical meaning remains the same: e.G.,

- •2. Analysis of the Linguistic Peculiarities Introduced by Various Ethnic Groups in the Course of American History a). American Indian Languages and their Influence

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 12 tourist attractions in the united states

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •References

Questions for discussion

What other names of the U.S.A. do you know?

How can the U.S. area be compared with other countries’ ones?

Why do many people think the U.S.A. consists of 51 states?

What is the political division of the U.S.A.?

How does the geography of the U.S.A. vary across its immense area?

What rivers (deserts) play an important role in the economy of the U.S.A.?

In what way do the major cultural regions of the U.S.A. differ?

What were the reasons of serious pollution problems the U.S.A. faced in the second half of the 20th century?

What advances the process of the U.S. regions’ Americanization?

What role was played by New England and the Middle Atlantic states in the 19th-century American expansion?

What gives the South its unmistakable identity?

What Western states don’t share with the rest the West's concern over the scarcity of water?

What has encouraged Midwesterners to direct their concerns to their own domestic affairs, avoiding matters of wider interest?

What are the attractions of the Sunbelt?

Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 1. From the 16th century to the american revolution

This lecture tells us how the U.S.A. developed from colonial beginnings in the 16th century, when the first European explorers arrived, until modern times. The lecture consists of three parts.

Part 1 covers the period between the colonization of America and ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1789. It describes:

European exploration of North America

colonial America

the American Revolution

the 1st and the 2nd Continental Congresses, the Constitutional Convention,

the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights

Key Words and Proper Names: acquisition of land, amendment, cannibalism, cash crop, exchange of species, indentured servants, indigenous tribe, indigo, mariner, militia, mob, nobles, the pursuit of happiness, plunder the wealth, persecution, redeemer nation, scarce, self-governance, slave trade;

the Boston Massacre, the Chesapeake Bay, John Cabot, Colony of Roanoke, the Battles of Lexington, Concord and of Saratoga, Delaware, the Great Awakening, Francis Drake, Jamestown, Federalists and Anti-federalists, the Intolerable Acts, the London Virginia Company, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Mayflower Compact, Nova Scotia, Pilgrims and Puritans, Pocahontas, Plymouth Colony, the Quakers, the Royal Proclamation, Squanto and Samoset, the Stamp Act, the Sugar and Currency Acts, the Tea Act , the Townshend Act.

European Exploration: It is well known that America was discovered by Ch. Columbus in 1492. But as history tells us, Columbus was not the first European to reach the continent. Scandinavians traveled to North America from Greenland in the 11th century and set up a short-lived colony in Nova Scotia. There is also a speculation that an obscure mariner had traveled to the Americas before Columbus and provided him with maps for his later claims. Some said European fishermen had discovered the fishing waters off eastern Canada by 1480.

However, the first recorded voyage to North America was made by John Cabot or Giovanni Caboto, an Italian navigator in the service of England, who sailed from England to Newfoundland in 1497.

Interesting to know: On 5 March 1496 King Henry VII of England gave J. Cabot letters patent with the following charge: ...free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of pagans and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

What distinguishes Columbus’s first voyage from all other early voyages of the past is the following: less than two decades later the existence of America became known in Europe. Columbus’s voyages led to a relatively quick, general and lasting recognition of the existence of the New World by the Old World, to the Columbian exchange of species (both those harmful to humans, such as viruses, bacteria, and diseases, and beneficial ones, such as tomatoes, potatoes, corn, and horses), and the first large-scale colonization of the Americas by Europeans.

The voyages also inaugurated ongoing commerce between the Old and New Worlds.

Before Columbus, several flourishing civilizations had existed in the Americas for centuries. The earliest inhabitants of America may have arrived over 25,000 years before Columbus. There were discovered remains from the first large building projects, dating back to 500 B.C. - 500 A.D., consisting of large ceremonial earthworks or mounds.

These structures proved that by 1492 American civilizations had reached a level of culture, which included personal wealth, fine buildings, expert craftsmanship, and religions.

The European colonization of the Americas forever changed the lives and cultures of the Native inhabitants of America. Up to 80% of indigenous Americans may have died from epidemics of imported diseases such as smallpox, and many tribes and cultures were completely eliminated in the course of European westward expansion.

Colonial America: Starting with the late 16th century, England, Scotland, France, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands began to colonize eastern North America. European settlers came from a variety of social and religious groups; they established small colonies and traded with the indigenous peoples.

But, only the English established colonies of agricultural settlers, who were interested less in trade and more in the acquisition of land. That fact was decisive in the long struggle for control of North America.

The first Englishmen also hoped to find gold or a passage through the Americas to the Indies. Other early English explorers such as Francis Drake arrived in the Americas to plunder the wealth of the Spanish settlers.

English migrants came to America for two main reasons. The first reason was religious tied to the English Reformation. Groups of colonists came to America searching for a) either an asylum to practice a religion without persecution or b) a refuge to begin a new and holier settlement where complete theological agreement could be found.

The second reason for English colonization was economic, because between 1530 and 1680 the population in England doubled and the land became scarce. Many of England’s largest landholders fenced the lands, and raised sheep for the expanding wool trade. The result was a growing number of poor, unemployed, and desperate English men and women. They were recruited by rich Americans and became indentured (contracted) laborers. American landowners even paid for a laborer’s passage to America if he signed the contact to serve them for several years.

The main waves of settlers in North America came in the 17th century. At first, most immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants. Between the late 1610’s and the American Revolution, the British shipped about 50,000 convicts to its American colonies. So, as you see as you see from the above said, the colonists who came to the New World were not a homogeneous mix; they belonged to different social and religious groups and came to the new continent for different reasons. And they created colonies with very different social, religious, political, and economic structures.

Early colonial attempts: The first permanent European settlement in North America was founded by the Spanish, it was at Saint Augustine, Fla., in 1565.

The first English attempt made in 1586, notably the Colony of Roanoke, resulted in failure. The “Lost” Colony of Roanoke was established off the coast of today's North Carolina by Sir Walter Raleigh. The second resupply ship, delayed for several years by circumstances in England, found no trace of the colonists, discovering only the mysterious word “CROATOAN” carved on a tree. Over a hundred men, women, and children had disappeared in the middle of their daily tasks.

England made its first successful efforts only at the start of the 17th century. It was Jamestown, established in 1607 in a region called Virginia, on a small river near the Chesapeake Bay.

All in all, the British settled Jamestown, Va. (1607); Plymouth, Mass. (1620); Maryland (1634); and Pennsylvania (1681). The English took New York, New Jersey, and Delaware from the Dutch in 1664, a year after English noblemen began to colonize the Carolinas.

By 1733, English settlers had founded 13 colonies along the Atlantic Coast, from New Hampshire in the North to Georgia in the South (Fig.3).

Fig. 4. 13 British colonies along the Atlantic Coast of North America

Historians typically recognize four regions in the lands that later became the eastern United States. They are: New England, the Middle Colonies, the Chesapeake Bay and the Southern Colonies.

The Thirteen Colonies’ territory ranged from what is now Maine (then part of the Province of Massachusetts Bay) in the north to Georgia in the south. They are listed in geographical order, from the north to the south. Thus, New England included New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut; the Middle Colonies – Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Delaware; the Chesapeake Bay – Virginia, Maryland; and the Southern Colonies – North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Now let’s discuss some of these colonies in detail.

The Chesapeake Bay region: The first truly successful English colony was Jamestown or Virginia established in 1607 in a region called Virginia (named in honor of Queen Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen”). It lay on an island in the James River, near its Chesapeake Bay estuary. The venture was financed and coordinated by the London Virginia Company, a joint stock company looking for gold. Its first years were extremely difficult, with very high death rates from disease and starvation, wars with local Indians, and little gold.

Archaeological findings have indicated that the entire region was struck by the most severe drought in centuries. American Indians were not very willing to give away their corn, and the colonists, without a harvest, starved; they named the winter the Starving Times. Only a third of the colonists survived the first winter. In fact, source documents indicate that some even turned to cannibalism. However, the colony survived, in large part due to the efforts of an enigmatic figure named John Smith. He behaved like an uncompromising, autocrat of the colony. His motto was “No work, no food.” He put the colonists to work, and befriended Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan, who was able to supply the colony with more food. John Smith had saved the colony, but it had yet to turn a profit.

Gold was nowhere to be found. Finally, in 1612, John Rolfe with the help of the above mentioned Pocahontas, who became his wife, introduced the cultivation of tobacco as a cash crop. The new product earned fabulously high profits in the first year, and substantially lower but still extraordinary ones in the second year.

By the late 17th century, Virginia's export economy was largely based on tobacco. As cash crop producers, Chesapeake plantations were heavily dependent on trade with England. New, richer settlers came in to take up large portions of land, build large plantations. Tobacco cultivation was labor-intensive. To provide this labor, the colonists first relied on white indentured servants, but starting with 1619 turned into the slave trade, which was already bringing large numbers of Africans to the sugar-producing islands of the Caribbean. Starting with 1676, African slavesrapidly replaced indentured servants as Virginia's main labor force. Tobacco continued to be the mainstay of the region’s economy for two centuries.

New England: The next successful English colonial venture was founded by two separate religious groups. Both demanded greater church reform and elimination of Catholic elements remaining in the Church of England. But whereas the Pilgrims sought to leave the Church of England, the Puritans wanted to reform it by setting an example of a holy community.

The first settlers who came to America for religious reasons were the Pilgrims.

The Pilgrims were a small Protestant sect based in England and the Netherlands. One group sailed on the Mayflower to the New World.

The Mayflower Compact, signed by the Pilgrims before disembarking, established precedents for the pattern of representative self-government and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies. They established a small Plymouth Colony on December 21, 1620; which later merged with the Massachusetts Bay colony. John Carver was their first leader and first elected colonial governor in American history. After his death his position was taken by William Bradford.

Like the settlers at Jamestown, the Pilgrims had a difficult first winter, having had no time to plant crops. Most of the settlers died of starvation, including the leader, John Carver. Later in 1621, the colonists enlisted the aid of Squanto and Samoset, two American Indians who had learned to speak some English. With the help of friendly Indians, the Pilgrims were able to build houses and raise food crops. That fall brought a bountiful harvest, and the first Thanksgiving was held. To show how the Pilgrims felt about the Indians’ help, they invited the Indians to share their first Thanksgiving feast.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new, pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived.

The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit, and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation". In search of religious freedom they fled England and in America attempted to create a "nation of saints" or a "City upon a Hill": an intensely religious, thoroughly righteous community designed to be an example for all of Europe.

Economically, Puritan New England fulfilled the expectations of its founders. Unlike the cash crop-oriented plantations of the Chesapeake region, the Puritan economy was based on the efforts of self-supporting farmsteads, which traded only for goods they could not produce themselves. There was a generally higher economic standing and standard of living in New England than in the Chesapeake. Along with agriculture, fishing, and logging, New England became an important mercantile and shipbuilding center, serving as the hub for trading between the southern colonies and Europe.

The political structure of the Puritan colonies is often misunderstood. Officials were elected by the community, but only white males who were members of a Congregationalist church could vote. Officials had no responsibility to “the people,” their function was to serve God by best overseeing the moral and physical improvement of the community. However, it was not a theocracy either — Congregationalist ministers had no special powers in the government. Thus, in the political structure of Puritan society one could see both the democratic form and the emphasis on civic virtue that was to characterize post-Revolutionary American society. Although some characterize the strength of Puritan society as repressively communal, others point to it as the basis of the later American value on civic virtue, and an essential foundation for the development of democracy.

Socially, the Puritan society was tightly knit. No one was allowed to live alone for fear that their temptation would lead to the moral corruption of all Puritan society. Because marriage took place within the geographic location of the family, during several generations many towns were more like clans, composed of several large, intermarried families. The strength of Puritan society was reflected through its institutions, specifically, its churches, town halls, and militia. All members of the Puritan community were expected to be active in all three of these organizations, ensuring the moral, political, and military safety of their community.

Two other colonies were founded in 1636 in New England. The Connecticut Colony was an English colony originally known as the River Colony; it was organized as a haven for those Puritans who were not happy with the strict morals and dominating religious hypocrisy in Massachusetts.

The Providence Plantation or the Rhode Island Colony was founded by Roger Williams, who preached religious toleration, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England. R. Williams agreed with his fellow settlers on an egalitarian constitution providing for majority rule “in civil things” and “liberty of conscience”.

Both colonies became a home for many refugees from the Puritan community.

The Middle Colonies: The Middle Colonies were characterized by a large degree of diversity: religious, political, economic, and ethnic. They were called the Middle Colonies because they lay between New England and other colonies to the south.

The Middle Colonies consisted of the present-day states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Maryland belonged both to the Middle Colonies and the Chesapeake. The Dutch colony of New Netherland was taken over by the British and renamed New York but large numbers of Dutch remained in the colony. Many GermanandIrish immigrants settled in these areas, as well as in Connecticut.

Pennsylvania, one of the most successful colonies, began when the Duke of York gave a large area to William Penn. In 1682, Penn started planning a colony called Pennsylvania. Penn belonged to a small religious group called the Friends, or Quakers. Pennsylvania was a colony where Quakers found freedom. Settlers came from all over Europe, many were from Germany. Penn also tried to be friendly with the Indians. He signed many peace agreements with his Indian neighbors. Pennsylvania soon became the largest and wealthiest colony. One part of the colony was later separated from Pennsylvania and became the colony of Delaware in 1701. Swedish people had earlier settled in Delaware and had brought a new idea to America - to build cabins made of logs.

The first group of Catholic settlers landed in America in 1634. They called their colony Maryland after Queen Mary, England's last Catholic ruler. One of the settlements was named after Lord Baltimore, the founder of the colony. Maryland became a prosperous colony of small farms and tobacco plantations where crops were tended by workers who lived on the property. Later, more settlers came to live in the colony, and most of them were Protestants. So quarrels often broke out between Protestants and Catholics, and Lord Baltimore had a law passed that allowed all people to worship as they pleased.

The South: The Southern Colonies are Georgia, the two Carolinas and Virginia, with the inclusion of Maryland (always a borderland), which is sometimes grouped with the Middle Colonies.

Life in the Southern Colonies centered around plantations which were cultivating rice, tobacco, and indigo (used for making a blue dye). There were few cities. Southern plantations depended on slavery. By 1750, there were more slaves than free people in the South.

Carolinas: Carolina was not settled until 1670, and even then the first attempt failed because there was no incentive for emigration to the south. The cultivation of rice was introduced during the 1690’s by Africans from the rice-growing regions of West Africa and Carolinas became rich.

Georgia: James Oglethorpe, an 18th century British Member of Parliament, established Georgia Colony as a common solution of two problems. At that time, tension between Spain and Great Britain was high, and the British feared that Spanish Florida was threatening the British Carolinas. Oglethorpe decided to establish a colony in the contested border region of Georgia and populate it with debtors who were imprisoned in Great Britain. This plan helped both rid Great Britain of its undesirable elements and provide her 13 American colonies with a base from which to attack Florida. Georgia initially failed to prosper, but eventually the moralistic restrictions (like alcohol and other forms of supposed immorality) were lifted, slavery was allowed, and it became as prosperous as the Carolinas.

British colonial government: The 3 forms of colonial government were provincial, proprietary, and charter. Under the feudal system of Great Britain, these were all subordinate to the monarch, with no explicit relationship with the British Parliament.

The colonies’ systems of governance was modeled after the British constitution of the time - with the king corresponding to the governor, the House of Commons to the colonial assembly, and the House of Lords to the Governor's council. The codes of law of the colonies were often drawn directly from British law; which survives even in the modern U.S.

By the 1720’s, most colonies had an elected assembly and an appointed governor. Governors technically had a great power. They were appointed by the king and represented him in the colonial government. Governors also had the power to make appointments. But the assemblies had the “power of the purse”. Only they could pass revenue bills. They often used their influence over finances to gain power in relation to governors and control over appointments. Colonists viewed their elected assemblies as defenders against the king, against Parliament, and against colonial governors.

In 1770, the 13 colonies had a population of 2.6 million, about one-third that of Britain; and nearly one in five Americans was a black slave. Though ‘subject to British taxation, the colonies had no representation in the Parliament of Great Britain’.

Although each of the colonies was different from the others, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries several events and trends took place that brought them together in various ways and to various degrees and led to the Revolution.

The Great Awakening: This event was very important for the unification of the religious background of the colonies; it was a Protestant revival movement that took place between the 1730’s and 1740’s. The movement fueled interest in both religion and religious liberty. It began with Jonathan Edwards, a Massachusetts preacher who sought to return to the Pilgrims' strictCalvinistroots and to reawaken the "Fear of God." Preachers traveled across the colonies and preached in a dramatic and emotional style, they shared with colonists their religious beliefs and views and even their every day concerns which were quite common for all colonists and in this way united the interests of scattered settlements across the colonies. This exchange of ideas was a small civic and democratic step towards the unification of the colonies.

The preachers called themselves the “New Lights”, as contrasted with the “Old Lights”, who disapproved of their movement. To promote their viewpoints, the two sides established academies and colleges, including Princeton and William and Mary College. The Great Awakening has been called the first truly American event. Methodism became the prevalent religion among colonial citizens after the First Great Awakening.

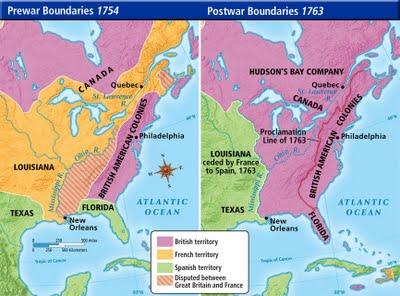

Another event in the long process of unification was the French and Indian War or the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763). This war was the American extension of the general European conflict known as the Seven Years' War. Increasing competition between Britain and France, especially in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley, was one of the primary origins of the war. As the French were supported by Indians, the American colonists called the war the French and Indian War.

The French and Indian War was an important event in the political development of the colonies. The influence of the main rivals of the British Crown in the colonies and Canada - the French and North American Indians - was significantly reduced. Moreover, the war effort resulted in greater political integration of the colonies, as symbolized by Benjamin Franklin's call for the colonies to “Join or Die”.

During the war the colonies identified themselves as a part of the British Empire and British military and civilian officials increased their presence in the lives of Americans. The British soldiers sent by the British government, were joined by men from Virginia.

But the war also increased a sense of American unity. It caused American men to travel across the continent and fight alongside men from different, yet still American backgrounds. Throughout the war British officers trained American ones for battle (e.g., young Virginian colonel named George Washington), that fact would later benefit the Revolution to come.

The war resulted in vast territorial acquisitions (Fig.4). In the Treaty of Paris (1763), France surrendered its vast North American empire to Britain. Before the war, Britain held the 13 American colonies, most of present-day Nova Scotia, and most of the Hudson Bay watershed. After the war, Britain gained all French territory east of the Mississippi River, including Quebec, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio valley. Britain also gained the Spanish colonies of East and West Florida. The British victory over the French in 1763 guaranteed Britain political control over its 13 colonies. But in removing a major foreign threat to the 13 colonies, this war also largely removed the colonists' need of the British protection.

Fig. 5. Territorial acquisitions after the French and Indian War

From unity to revolution: What really united the colonies in their negative attitude to Britain was the booming import of British goods. Using the colonies of North America as a market for British goods, Britain increased exports to that region by 360% between 1740 and 1770. At the same time American rich manufacturers experienced difficulties in selling their American produce.

The general sentiment of inequity that arose soon after the Treaty of Paris was intensified by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited colonists’ settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains on the land which had been recently captured from France. The colonists resented the measure and regarded it as unnecessary and draconian. And the proclamation was never enforced. At the end of the 18th century, a number of Parliament Acts aggravated the situation in the colonies to the extreme.

In fact, the cost of the Seven Years War for the British was a bad need of money, and consequently Parliament introduced new taxes in America. Parliament passed the Sugar and Currency Acts in 1764. The Sugar Act strengthened the customs service. The Currency Act forbade colonies to issue paper money. The Stamp Act of 1765 required all legal documents, licenses, commercial contracts, newspapers, pamphlets, and playing cards to carry a tax stamp.

In 1767, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend drew up new taxes on imports (tea, lead, paper, glass, etc.) that Americans could receive only from Britain; the document was called the Townshend Act. The revenue from these taxes went on the salaries of colonial governors and judges, making them independent of the colonial assemblies. Townshend moved many units of the British army to the centers of white population and dissolved the assemblies (First Quartering Actof 1765, SecondQuartering Actof 1774).

Americans challenged the right of the British parliament to force taxes on them, using the slogan no taxation without representation. They were angry that the British prevented them from trading with other nations and taking land in the western part of America. Soon they started to protest openly and attack men who accepted appointments as Act commissioners, usually forcing them to resign. They boycotted all imported British goods — particularly tea. The British responded by landing troops at Boston in October 1768. Tensions between townspeople and soldiers were constant for the next year and a half.

On March 5, 1770, tensions exploded into the Boston Massacre, when British soldiers fired into a mob of Americans, killing 5 men.

In Boston, on December 16, 1773, some patriots dressed as Native Americans went on board ships used to transport tea. They threw the tea into the water, an incident that became known as the Boston Tea Party.

Britain responded to this Boston Tea Party with the Intolerable Acts of 1774, which closed the port of Boston until Bostonians paid for the tea. The Acts also permitted the British army to quarter its troops in civilian households.

Tensions between American colonists and the British during the period of the 1760’s and early 1770’s led to the American Revolutionary War, fought from 1775 through 1781.

Continental Congresses: In September 1774, the First Continental Congress gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Each colony sent its delegates (aka Founding Fathers). The Congress refused to recognize the authority of British Parliament, it decided to stop all trade with Britain, and to start collecting guns and practice using them. On June 14, 1775, the Congress established a Continental Army under the command of George Washington and dispatched it to Boston, where there were clashes between local militia and a British Army.

The Battle of Lexington and Concord in 1775 marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

On May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, began to organize a federal government for the 13 colonies; taking over governmental functions previously exercised by the King and Parliament, and prepare state constitutions for their own governance.

Proclaiming that “all men are created equal” and endowed with “certain unalienable Rights,” the Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, drafted largely by Thomas Jefferson, on July 4, 1776. The drafting of the Declaration was the responsibility of a committee of five, which included, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, but the style of the document is attributed primarily to Thomas Jefferson. That date is now celebrated annually as America's Independence Day.

The Declaration said that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.” In the Declaration, Jefferson explained why the colonies had decided to fight against British rule. The Declaration of Independence gave Americans an even stronger belief in their cause.

In August 1776, King George III proclaimed the colonies to be in rebellion. That year, the prospects for American victory seemed small. Britain had a population more than 3 times that of the colonies, and the British army was large, well-trained, and experienced. The Americans had undisciplined militia and only the beginnings of a regular army or even a government. But they fought on their own territory, and in order to win they did not have to defeat the British but only to convince the British that the colonists could not be defeated.

The turning point in the war came in 1777 when American soldiers defeated the British Army at Saratoga, New York. France had secretly been aiding the Americans. After the victory at Saratoga, France and America signed treaties of alliance, and France provided the Americans with troops and warships. Spain and Holland sent supplies and money. Polish soldiers also came to America to fight for the American cause.

The last major battle of the American Revolution took place at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. A combined force of American and French troops surrounded the British and forced their surrender.

Fighting continued in some areas for two more years, and the war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, by which England recognized American independence and abandoned the territory from the Atlantic to the Mississippi.

Interesting to know: Yankee Doodle is the song, which told the story of a poorly dressed Yankee simpleton, or “doodle.” It was popular with British troops; they played it as they marched to battle on the first days of the Revolutionary War. The rebels quickly claimed the song as their own and created dozens of new verses that mocked the British, praised the new Continental Army, and hailed its commander, George Washington.

By 1781, when the British surrendered at Yorktown, being called a “Yankee Doodle” had gone from being an insult to a point of pride, and the song had become the new republic’s unofficial national anthem.

During the war years, the Second Continental Congress acted as a central government, but it wasn’t a proper government after the war. In 1777, the members of Congress worked out a plan for a union of the states. The plan was called the Articles of Confederation. In 1781, the new national government started. The purpose of the government, as Thomas Jefferson said, was to protect the rights of the people. Those rights included "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

The Confederation was not a strong government as none of the states wanted to give up much of their own power - there were too many things the government of the Confederation could not do. E.g., the Confederation Congress could not raise money by taxes; it could only ask the states to raise money for the national government. In fact, the Articles of Confederation called the new nation a “league of friendship,” which showed that the states thought of themselves as friendly allies rather than as part of a strong single nation. Many Americans became worried about the future. How could they win the trust of other nations if they refused to pay their debts? How could the country prosper if the states continued to quarrel among themselves?

The Constitutional Convention: The need for a more powerful and complete federal government led, in 1787, to the calling of the Constitutional Convention. It met in Philadelphia through the summer of 1787 and wrote a Constitution. After much discussion and compromise, the convention approved a new constitution on September 17, 1787 and, by June of 1788 the Constitution had been ratified by 9 states and became official.

In 1789, the Constitution of the United States was put into operation, and George Washington was elected the first President of the United States.

The Constitution called for a federal government, limited in scope, but independent of and superior to the states. It was able to tax, and was equipped with a two house Legislature and Executive and Judicial branches.

The U.S. Constitution established the separation of powers between three different branches of government. The legislative branch or Congress consists of 2 parts: the House of Representatives and the Senate. Its function is to enact laws. The executive branch led by a President and Vice-President enforces laws. The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court and a number of lower courts created by Congress which interpret and decide questions of federal and state law. So, each branch of government has its own responsibilities and cannot take action in areas assigned to the other branches.

Together with this separation of powers, the Constitution introduced a system of checks and balances so that each branch had some power over the other two in order to stop them from becoming too powerful. In this way the Constitution prevents tyrannical abuses of authority through the separation of powers:

The national legislature, or Congress, embodied the key compromise of the Convention, between the small states, which wanted to retain the power they had under the one state/one vote (i.e., equal representation of all states), and the large states, which wanted the weight of their larger populations and wealth to have a proportionate share of power (i.e., equal representation of all population of the states). So, the upper House, the Senate, represents the states equally, while the lower House, House of Representatives, is elected from districts called constituencies of approximately equal population. As a result states with bigger population have a bigger representation in it.

Thus, the Constitution went into effect in 1789 and has not changed ever since.

The Constitution spells out in its seven articles (sections) the powers of the federal government and the states. Later amendments expanded some of these powers and limited others.

Article I vests (places) the legislative power of the federal government in Congress. Only Congress can enact general laws applicable to all the people.

Article II vests the executive power in the president, including the authority to appoint federal officials and to prosecute federal crimes.

Article III vests the federal judicial power, including the power to conduct trials, in the Supreme Court and in other federal courts that Congress creates. Neither Congress nor the president or executive branch officials can declare a person guilty. Only a judge or jury can make these decisions.

Article IV defines and delineates the rights of the states and of the federal government. States must accept most laws and legal decisions made in other states. The states must offer most fundamental legal rights to both residents and nonresidents of the state. People accused of serious crimes cannot take refuge in other states.

Congress controls the admission of new states. Congress and the legislatures of the states involved must approve the merger of two states or the creation of a new state within the boundaries of an existing state.

The government has the right to use federal buildings, lands, and property in almost any way it sees fit. The federal government has an obligation to protect the political and physical integrity of the states. The federal government must take responsibility for stopping invasions and, if the states ask, to squelch (suppress) domestic unrest.

Article V defines the ways to amend the Constitution. Both the states and Congress can propose amendments to the Constitution. I will speak about it later.

Article VI binds all government officials, including those at the state level, to support the Constitution and federal laws. All laws in the U.S.—federal, state, and local—must be consistent with the Constitution. All judges must hold the U.S. Constitution above all other law. Members of Congress, the state legislatures, state and federal judges, and state and federal executive officials must agree to support the Constitution.

Article VI leaves other powers to the states to exercise at their discretion, with two exceptions. First, the Constitution is the “supreme law,” so the states cannot make laws that conflict with federal laws. Second, the Constitution guarantees to the people certain civil liberties (the right to be free of government interference) and civil rights (the right to be treated as a free and equal member of the country).

Article VII defines the number of states needed for its ratification. Only 9 of the original 13 states were needed to approve the Constitution. This Article is obsolete.

Ways to amend the Constitution: 1) Congress can propose an amendment, provided that 2/3ds of the members of both the House and the Senate were in favor of it. 2) Or the legislatures of two of the states can call a convention to propose amendments. After the Conventional Congress proposes an amendment, it then requires approval by 2/3ds of the state legislatures, or 2/3ds of special state conventions, whichever Congress specifies. By the way, the second method, which allows states to propose an amendment, has never been used so far.

The Constitution took away many of the states’ powers and specified the powers held by the states and the people. This division of powers between the states and the national government was called federalism. Those, who advocated the Constitution, took the name Federalists, and quickly gained supporters throughout the nation. Opponents of the plan for stronger government took the name Anti-federalists. They feared that a government with the power to tax would soon become as despotic and corrupt as Great Britain had been only decades earlier. Thomas Jefferson, who was serving as Ambassador to France at that time, was neither a Federalist nor an Anti-federalist, but decided to remain neutral.

The original Constitution did not include a bill of rights because the delegates to the Constitutional Convention did not think it necessary to set down a list of rights.

When the Constitution went before the states for ratification, members of the Federalist Party, who favored the ratification, found out that the failure to include a bill of rights had been a strategic error and refused to ratify the Constitution until it was changed to give citizens more protection against the wrong use of power by the government. So, the Federalists were for a bill of rights, but the anti-Federalists were against. Even Jefferson sided with the advocates of a bill of rights. Human rights, he argued, were something “no just government should refuse, or rest on inference (here implication).”

The Bill of Rights, forbidding federal restriction of personal freedoms and guaranteeing a range of legal protections, was adopted in 1791. It consisted of 10 amendments out of 12 proposed by the Congress. One was not ratified, and one was ratified as the 27th Amendment.

The First Amendment protected the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and religion from federal legislation. The Second and Third Amendments guaranteed the right to bear arms and made it difficult for the government to house soldiers in private homes — provisions favoring a citizen militia over a professional army. The Fourth through Eighth Amendments defined a citizen’s rights in court and when under arrest. The Ninth Amendment stated that the enumeration of these rights did not endanger other rights, and the Tenth Amendment said that powers not granted the national government by the Constitution remained with the states and citizens.

Thus, the Bill of Rights guarantees Americans freedom speech, religion, and the press. Americans have the right to assemble in public places, to protest government actions, and to demand change. There is a right to own firearms. Because of the Bill of Rights, neither police officers nor soldiers can stop and search a person without good reason. Nor can they search a person’s home without permission from a court to do so. The Bill of Rights guarantees a speedy trial to anyone accused of a crime. The trial must be by jury if requested, and the accused person must be allowed representation by a lawyer and to call witnesses to speak for him or her. Cruel and unusual punishment is forbidden.

Since 1791, 17 other amendments have been added to the Constitution. Perhaps most important of these are the Thirteenth and Fourteenth, which outlaw slavery and guarantee all citizens equal protection of the laws, and the Nineteenth, which gives women the right to vote.

Federalists and Anti-federalists, the emerging Party system: The Constitution makes no mention of political parties, and the Founding Fathers regularly ridiculed political “factionalism.” As mentioned before, the struggle over the ratification of the Constitution, however, suggested the first outlines of the system of political parties, which was to later emerge.

The Federalists, who had advocated the Constitution, enjoyed the opportunity to put the new government into operation, while after the adoption of the Constitution, the Anti-federalists, never as well-organized, effectively ceased to exist.

However, the ideals of states’ rights and a weaker federal government were in many ways absorbed by the growth of a new party, the Republican, later Democratic-Republican Party or Democratic Party, which eventually assumed the role of loyal opposition to the Federalists, and finally took control of the federal government in 1800, with the election of Thomas Jefferson as President.