- •Уо «белорусский государственный экономический университет»

- •Contents

- •Lecture 1 geography and cultural regions of the u.S.A.

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 1. From the 16th century to the american revolution

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 2. From the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 2 history of the united states Part 3. The u.S. In the 20th and 21st centuries

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 3 federal government of the united states

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 4 u.S. Economy and demographics

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 5 the united states - nation of immigrants

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lectures 8 the united states culture and american identity

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 9 american cultural traits

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 10 american english

- •A). American Indian languages and their influence

- •1. British English vs. American English

- •When speaking about lexico-semantic differences one should pay attention to structural variants of words in be and ae. They differ in affixes while lexical meaning remains the same: e.G.,

- •2. Analysis of the Linguistic Peculiarities Introduced by Various Ethnic Groups in the Course of American History a). American Indian Languages and their Influence

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •Lecture 12 tourist attractions in the united states

- •Summary

- •Questions for discussion

- •References

Questions for discussion

What achievements won Woodrow Wilson a firm place in American history as one of the nation’s foremost political reformers?

What caused the stock market crash on Thursday 29, October 1929?

Why was the New Deal introduced, and what was it about?

What was the U.S. foreign policy before WWII?

What was the origin of the Cold War policy and how did the world balance on the brink of war for about 50 years?

Why is the issue of the U.S. civil rights connected with the name Martin L. King, Jr.?

How did the U.S. economy develop between 1946 and 2014?

When were most important social programs introduced and by whom?

What is Reaganomics (the New Economy of the Tech Bubble) about?

What do you know about the Bush Doctrine and the consequences of its implementation?

What was done by Obama’s administration to overcome the economic difficulties of 2008-2010 credit crunch?

How did the U.S. - Russia bilateral relations develop between 2009-2014?

Lecture 3 federal government of the united states

This lecture will give us a thorough study of how the United States of America is governed. It describes:

the U.S. legislative branch

the U.S. executive branch

the U.S. judicial branch

the U.S. separation of powers and system of checks and balances

The U.S. Constitution of 1789 sets down the basic framework of American government. The U.S. government’s type is defined as the Constitution-based federal republic with strong democratic traditions.

The American Constitution is based on the doctrine of separation of powers between the Executive (the Presidency), Legislative (Congress) and Judiciary (the Courts).

Government power was further limited by means of a dual system of government: the federal government and the state governments. This system gives the federal government the powers and responsibilities to deal with problems facing the nation as a whole (foreign affairs, trade, control of the army and navy, etc.). The remaining responsibilities and duties of government (by the way, not mentioned in the Constitution) were reserved to the individual state governments.

The basic laws of the U.S. are set down in major federal legislation, such as the U.S. Code. The federal legal system is based on statutory law, while most state and territorial law is based on English common law, with the exception of Louisiana (based on the Napoleonic Code due to its time as a French colony) and Puerto Rico (based on Spanish law).

Legislative branch

Article I of the Constitution grants all legislative powers of the federal government to Congress. It also defines its structure and powers. So, Congress is a bicameral legislature, consisting of two chambers: the House of Representatives (the “Lower House”) and the Senate (the “Upper House”).

Both Houses of Congress meet in the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The Senate is the conservative counterweight to the more populist and dynamic House of Representatives.

Interesting to know: During the American Revolutionary War and under the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the United States was named the Continental Congress. The first Congress under the current Constitution started its term in Federal Hall in New York City on March 4, 1789 and their first action was to declare that the new Constitution of the United States was in effect. The United States Capitol building in Washington, D.C. hosted its first session of Congress on November 17, 1800.

Congress of the United States: The House of Representatives consists of 435 members, each of whom is elected by a congressional district or constituency of roughly equal size (around 520,000 people) and serves a two-year term. Seats in the House are divided between the states on the basis of population, with each state entitled to at least one seat.

In the Senate, on the other hand, each state is represented by two members, regardless of population. As there are 50 states in the Union, the Senate consists of 100 members. Each Senator, who is elected by the whole state rather than by a district, serves a six-year term. Senatorial terms are scheduled so that approximately one-third of the terms expire every two years.

The Constitution vests in Congress all the legislative powers of the federal government. Congress, however, only possesses those powers enumerated in the Constitution; other powers are reserved to the states, except where the Constitution provides otherwise.

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress a direct jurisdiction for Washington, D.C. While Congress has delegated various amounts of this authority to the local government Washington, D.C., from time to time, Congress still intervenes in local affairs relating to schools, gun control policy, etc. Citizens of the District lack voting representation in Congress, though they do have three electoral votes in the Presidential elections. They are represented in the House of Representatives by a non-voting delegate (currently Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC)) who sits on committees and participates in debate but cannot vote. D.C. does not have representation in the Senate. So, citizens of Washington, D.C. are unique in the world. Attempts to change this situation, including the proposed District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, have been unsuccessful.

Insofar as passing legislation is concerned, the Senate is fully equal to the House of Representatives. The Senate is not a mere “chamber of review,” as is the case with the upper houses of the bicameral legislatures of most other nations.

Interesting to know: The U.S. Congress has fewer women in it than legislatures in other countries, but many more lawyers. The percentage of lawyers in Congress fluctuates around 45%. In contrast, in the Canadian House of Commons, the British House of Commons, and the German Bundestag, approximately 15% of members have law degrees.

Legislation: Each house of Congress has the power to introduce legislation on any subject dealing with the powers of Congress, except for the legislation dealing with gathering revenue (generally through taxes), which must originate in the House of Representatives (specifically the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means).

Congress has sole jurisdiction over impeachment of federal officials including presidents. The House has the sole right to bring the charges of misconduct which would be considered at an impeachment trial, andthe Senate has the sole power to try impeachment cases and to find officials guilty or not guilty. A guilty verdict requires a two-thirds majority in the Senate and results in the removal of the federal official from public office.

The Senate has oversight powers over the executive branch. The House also lacks two specific powers granted to the Senate.

1) Only the Senate can approve treaties negotiated and submitted by the president. However, the House has the power to withhold funding the implementation of such agreements, and thus has a leverage over many treaties.

2) The Senate also has the sole power to confirm cabinet members and other key government officers. Because these officials work on policies such as housing and agriculture that fall under the House control, however, they must work with committees in both chambers once in office.

The broad powers of the whole Congress are spelled out in Article I of the Constitution, they include: to levy and collect taxes, to borrow money for the public treasury, to make rules and regulations governing commerce among the states and with foreign countries, to make uniform rules for the naturalization of foreign citizens, to coin money, state its value, and provide for the punishment of counterfeiters, to set the standards for weights and measures, to establish bankruptcy laws for the country as a whole, to establish post offices and post roads, to issue patents and copyrights, to punish piracy, to declare war, to raise and support armies, to provide for a navy, to call out the militia to enforce federal laws, suppress lawlessness, or repel invasions, to make all laws for the seat of government (Washington, D.C.), to make all laws necessary to enforce the Constitution.

Some powers are added in other parts of the Constitution: to set up a system of federal courts (set out in Article III), to prohibit slavery (set out in the 13th Amendment), to enforce the right of citizens to vote, irrespective of race (set out in the 15th Amendment).

The 10th Amendment sets definite limits on congressional authority, by providing that powers not delegated to the federal government are reserved to the states or to the people.

Officers of Congress: The Constitution provides that the vice president shall be President of the Senate. The vice president has no right to vote, except in the case of a tie. The Senate chooses a President pro tempore to preside when the vice president is absent. The most powerful person in the Senate is not the president pro tempore, but the Senate Majority Leader (though quite often it is the same person).

The House of Representatives has its own presiding officer — the Speaker of the House. The Speaker is elected by the House and has important responsibilities, giving him a considerable influence over the President. Moreover, should the President and Vice-President die before the end of their term it is the Speaker who becomes President.

The Speaker and President pro tempore are always members of the political party with the largest representation in each house, aka the majority.

The committee process: One of the major characteristics of Congress is the dominant role that Congressional committees play in its proceedings. The Constitution does not specifically call for the establishment of U.S. Congressional committees. However, as the nation grew, so did the need for investigating pending legislation more thoroughly.

At present, the Senate has 16 standing (or permanent) committees; the House of Representatives has 20 standing committees. Each specializes in specific areas of legislation: foreign affairs, defense, banking, agriculture, commerce, appropriations, etc. Almost every bill introduced in either house is referred to a committee for study and recommendation. The committee may approve, revise, kill or ignore any measure referred to it. It is nearly impossible for a bill to reach the House or Senate floor without first winning committee approval.

In the House, a petition to release a bill from a committee to the floor requires the signatures of 218 members; in the Senate, a majority of all members is required.

In addition, each house can name special, or select, committees to study specific problems. Because of an increase in workload, the standing committees have some 150 subcommittees.

The majority party in each house controls the committee process. Committee chairpersonsare selected by acaucus of party members or specially designated groups of members. Minority parties are proportionally represented on the committees according to their strength in each house. Bills are introduced by a variety of methods:

a) some are drawn up by standing committees;

в) some by special committees created to deal with specific legislative issues;

с) some may be suggested by the president or other executive officers;

d) citizens and organizations outside Congress may suggest legislation to members,

e) individual members themselves may initiate bills.

After the introduction, the bills are sent to the designated (indicated) committees that, in most cases, schedule a series of public hearingsto permit presentation of views by persons who support or oppose the legislation. The hearing process, which can last several weeks or months, theoretically opens the legislative process to public participation. When a committee has acted favorably on a bill, the proposed legislation is then sent to the floor for an open debate.

In the Senate, the rules permit virtually unlimited debate. In the House, because of the large number of members, the Rules Committee usually sets limits. When debate is ended, members vote either to approve the bill, defeat it, table it (which means setting it aside and is tantamount to defeat) or return it to the committee. A bill passed by one house is sent to the other for action. If the bill is amended by the second house, a conference committee composed of members of both houses attempts to reconcile the differences.

Once passed by both houses, the bill is sent to the president, for constitutionally the president must act on a bill for it to become law.

The president has the option of signing the bill — at which point it becomes national law — or vetoing it. A bill vetoed by the president must be reapproved by a two-thirds vote of both houses to become law, this is called overriding a veto.

The president may also refuse either to sign or veto a bill. In that case, the bill becomes law without his signature 10 days after it reaches him (not counting Sundays). The single exception to this rule is when Congress adjourns after sending a bill to the president and before the 10-day period has expired; his refusal to take any action then negates the bill — a process known as the “pocket veto.”

Congressional powers of investigation: One of the most important non-legislative functions of Congress is the power to investigate. This power is usually delegated to committees — either to the standing committees, to special committees set up for a specific purpose, or to joint committees composed of members of both houses.

Investigations are conducted to gather information on the need for future legislation, to test the effectiveness of laws already passed, to inquire into the qualifications and performance of members and officials of the other branches, and, on rare occasions, to lay the groundwork for impeachment proceedings. Frequently, committees call on outside experts to assist in conducting investigative hearings and to make detailed studies of the issues.

Two important matters are attached to the investigative power: 1) to publicize investigations and their results, 2 ) to arouse public interest in the results of the investigation. Most committee hearings are open to the public and are widely reported in the mass media. Congressional investigations thus represent one important tool available to lawmakers to inform the citizenry and arouse public interest in national issues.

Informal practices of Congress: In contrast to European parliamentary systems, the selection and behavior of U.S. legislators has little to do with central party discipline. Traditionally members of Congress owe their positions to their districtwide or statewide electorate, neither to the national party leadership nor to their congressional colleagues. As a result, the legislative behavior of representatives and senators tends to be individualistic and idiosyncratic, reflecting the great variety of electorates they represent, and the freedom that comes from having built a loyal personal constituency.

The Congress is thus a collegial and not a hierarchical body. Power does not flow from top down, as in a corporation, but practically in every direction. There is comparatively minimal centralized authority, since the power to punish or reward is slight. Congressional policies are made by shifting coalitions that may vary from issue to issue.

The traditional independence of members of Congress has both positive and negative aspects. One benefit is that legislators are allowed to vote their consciences or, better to say, their constituents’ wishes that is inherently more democratic. The independence of Congressmen and Senators also allows much greater diversity of opinion than wouldn’t exist if Congressmen had to obey their leaders. Thus, although there are only two parties represented in the Congress, America’s Congress represents virtually every shade of opinion that exists in the land.

A newly emerged Congressional practice is the practice of the Speaker of the House only supporting legislation that is supported by his party, no matter whether or not he personally supports it or the majority of the House supports it.

Lobbyists: Congressional freedom of action also gives more power to lobbyists than in Europe or elsewhere. Lobbying is called the fourth branch of the American government. Many observers of Congress consider lobbying to be a corrupting practice, but others appreciate the fact that lobbyists provide information. Lobbyists also help write complicated legislation. Congressional lobbyists must be registered in a central database and only sometimes actually work in lobbies. Virtually every group - from corporations to foreign governments, to states, or to grass-roots organizations - employs lobbyists. There are about 35,000 registered Congressional lobbyists. Many lobbyists are former Congressmen and Senators, or relatives of sitting Congressmen. Former Congressmen are advantaged because they retain special access to the Capital, office buildings, and even the Congressional gym.

Executive branch

U.S. President: Article II of the Constitution establishes the Executive branch of Government. The head of the executive branch is the U.S. President, who is both the head of state and head of government. Under him or her is the Vice President and 14 heads of the federal executive departments. They are appointed by the President and confirmed with the “advice and consent” of the U.S. Senate. They form the Cabinet.

The president is the executive and Commander-in-Chief, responsible for controlling the U.S. armed forces and nuclear arsenal.

The president, the Constitution says, must “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” To carry out this responsibility, he presides over the executive branch of the federal government, a vast organization numbering about 4 million people, including 1 million active-duty military personnel. Within the executive branch itself, the president has broad powers to manage national affairs and the workings of the federal government.

The president may veto legislation passed by the Congress; he or she may be impeached by a majority in the House and removed from office by a two-thirds majority in the Senate for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The president may not dissolve the Congress or call special elections, but does have the power to pardon convicted criminals, give executive orders, and (with the consent of the Senate) appoint Supreme Court justices and federal judges. The incumbent President and Vice President are Barack H. Obama and Joe Biden, inaugurated on January 20, 2009.

Requirements to hold office: Section One of Article II of the U.S. Constitution establishes the requirements one must meet in order to become President. The president must be a natural-born citizen of the U.S. (or a citizen of the U.S. at the time the U.S. Constitution was adopted), be at least 35 years of age, and have been a resident of the United States for 14 years.

Under the Constitution, the President serves a four-year term. Amendment 22 (which took effect in 1951 and was first applied to Dwight D. Eisenhower starting in 1953) limits the president to either two four-year terms or a maximum of ten years in office should he have succeeded to the Presidency previously and served less than two years completing his predecessor’s term. Since then, four presidents have served two full terms: Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

Succession: The U.S. presidential line of succession is a detailed list of government officials to serve or act as President upon a vacancy in the office due to death, resignation, or removal from office (by impeachment and conviction). It begins with the Vice President and ends with the Secretary of Veterans Affairs. To date, no officer other than the Vice President has been called upon to act as President.

Presidential elections: U.S. presidential elections are held every 4 years on the first November Tuesday of a leap year. The President and the Vice President are the only two nationally elected officials in the U.S. Presidents are elected indirectly, through the Electoral College. Legislators are elected on a state-by-state basis; other executive officers and judges are appointed.

Many American voters are unaware of the Electoral College’s role, because they mistakenly believe that they directly elect their president and vice president. In fact, when they cast their ballots for president and vice president, they are voting for officials called electors who are assigned to each presidential candidate. But each state is entitled to a different number of electors which corresponds to the number of Senators and Congressmen from that state in Congress. All in all there are 538 electors; their number is equal to the number of legislators in the U.S. Congress plus 3 electors from Washington, D.C.

Current populous states with the most electors include California, Texas, Florida, New York, and Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio; they almost give half of the electors needed. When a candidate wins in these states, he wins the election.

In most U.S. states, the presidential candidate who wins a majority of the popular votes in a state also earns all the votes of the state’s Electoral College members. However, in this method of electing the president, a candidate can win the most Electoral College votes, and thus the presidency, even without winning the most popular votes in the country.

The modern presidential election process begins with the primary elections, during which the major parties (the Democrats and the Republicans) each select a nominee to unite behind; the nominee, in turn, selects a running mate to join him on the ticket as the vice presidential candidate. The two major candidates then face off in the general election; they participate in nationally televised debates before Election Day and campaign across the country to explain their views and plans to the voters. Much of the modern electoral process is concerned with winning swing populous states, through frequent visits and mass media advertising drives.

In accordance with Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 8 of the Constitution, upon entering office, the President must take the following oath or affirmation: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States”. Only presidents Franklin Pierce and Herbert Hoover have chosen to affirm rather than swear. The oath is traditionally ended with, “So help me God,” although for religious reasons some Presidents have said, “So help me.”

On Inauguration Day, usually January, 20th, following the oath of office, the President customarily delivers an inaugural address which sets the tone for his administration.

The executive departments: The day-to-day enforcement and administration of federal laws is in the hands of 14 executive departments, created by Congress to deal with specific areas of national and international affairs. The Department of Defense, e.g., runs the military services. The Department of Health and Human Services runs programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. The State Department advises the President on relations with foreign countries and runs the embassies. In addition, there are a number of independent agencies within the executive branch, for example the Central Intelligence Agency.

The heads of the departments, chosen by the president and approved by the Senate, form a council of advisers generally known as the president’s “Cabinet.” The Cabinet is thought to be a part of the executive branch of the U.S. federal government. However, the term “Cabinet” does not appear in the U.S. Constitution, where reference is made only to the heads of departments.

As a governmental institution, the Cabinet developed as an advisory body out of the president’s need to consult the heads of the executive departments on matters of federal policy and on problems of administration. Apart from its role as a consultative and advisory body, the Cabinet has no function and wields no executive authority. The president may or may not consult the Cabinet and is not bound by the advice of the Cabinet. Furthermore, the president may seek advice outside the Cabinet; a group of such informal advisers is known in American history as a “kitchen cabinet.” The formal Cabinet meets at times set by the president, usually once a week.

Because the executive departments of the federal government are equally subordinate to the president, Cabinet officers are of equal rank, but ever since the administration of George Washington, the Secretary of State, who administers foreign policy, has been regarded as the chief Cabinet officer.

Interesting to know: The first president of the United States, George Washington, quickly realized the importance of having a cabinet. Amongst his first acts he persuaded Congress to recognize the departments of Foreign Affairs (of State), Treasury, and War. Unlike contemporary European advisors who were given the title “minister,” the heads of these executive departments were be given the title of “secretary” followed by the name of their department. George Washington’s first Cabinet consisted of Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Knox as Secretary of War, and Edmund Randolph as Attorney General.

Secretary selection process: The 14 Cabinet secretaries are often selected from past and current American governors, senators, representatives, and other political office holders. Private citizens such as businessmen or former military officials are also common Cabinet choices. Because of the strong system of separation of powers, no Cabinet member can simultaneously hold an office in the legislative or judicial branches of government while serving in Cabinet, nor can they hold office in state government. Unlike the parliamentary system of government, Cabinet members are rarely “shuffled,” and it is rare for a Secretary to be moved from one department to another.

The officials in the U.S. Cabinet are strongly subordinate to the President. The main interactions that Cabinet members have with the legislative branch are regular testimonials before Congressional committees to justify their actions, and coordinate executive and legislative policy in their respective fields of jurisdiction.

Cabinet members can be fired by the President or impeached and removed from office by Congress. Commonly, a few Cabinet members may resign before the beginning of a second Presidential term. Usually, all Cabinet members resign shortly after the inauguration of a new President. Rarely, a popular or especially dedicated Cabinet member may be asked to stay, sometimes even serving under a new President of another party.

Judicial branch

Article III of the Constitution vests the judicial power in “one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time establish.” This means that apart from the Supreme Court, the organization of the judicial branch is left in the hands of Congress. Beginning with 1789, Congress created several types of courts and other judicial organizations, which now include federal courts, specialized courts, and administrative offices to help run the judicial system.

Federal courts — which include 94 district courts, 13 courts of appeals, and special courts such as the Court of International Trade and the Supreme Court — handle only a small part of the legal cases in the U.S. Most cases involve state and local laws, so they are tried in state or local courts rather than federal courts.

District Courts: Most federal cases start out in the district courts, which are trial courts — courts that hear testimony about the facts of a case. There are 94 district courts, including one or more in each state, one in the District of Columbia, one in Puerto Rico, and three territorial courts with jurisdiction over Guam, the Virgin Islands of the U.S., and other U.S. territories.

Courts of Appeals: The decision of a district court can be appealed to the second tier in the judicial branch, the courts of appeals. The appeals courts can consider only questions of law and legal interpretation, and in nearly all cases must accept the lower court’s factual findings. An appeals court cannot, for example, consider whether the physical evidence in a case was enough to prove a person was guilty. Instead, the appeals court might consider whether the district court followed appropriate rules in accepting evidence during the trial.

For appeals purposes, the U.S. is divided into 12 judicial areas called circuits. An additional appeals court, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, has nationwide jurisdiction over major federal questions.

Decisions of the appeals courts are final, unless the U.S. Supreme Court agrees to hear a further appeal. In district courts, most cases are heard by a single judge. In the appeals courts, cases are usually heard by a panel of three or more judges.

The differences between Federal Courts and State/Local Courts are represented in Table 1.

Special Courts: Congress has established several courts to decide cases arising within its legislative powers. These are called legislative courts because they lie outside of the Constitution’s Article III. E.g., the Court of Federal Claims hears cases of people who file claims against the government and seek money as a result. The Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces is the final appeals court for court-martial convictions in the armed forces. There is also a separate appeals court that deals with cases involving veterans’ benefits. The Tax Court tries and decides cases involving federal taxes, tax exemptions for charities, and other tax-related matters.

Table 1. The difference between Federal Courts and State/Local Courts.

|

Federal Courts |

State/Local Courts |

|

Some Types of Cases Heard:

|

Some Types of Cases Heard:

|

|

Affect on federal civil rights law: Rulings issued by federal courts are more authoritative interpretations of federal laws than state courts, and the Supreme Court has the final definitive say on issues regarding federal civil rights law. |

Affect on federal civil rights law: While state courts sometimes address federal laws, the federal courts' interpretations of federal law generally carries more persuasive weight. |

As you see, federal courts have a leading role in judging cases and interpreting laws, rules, and other government actions, and determining whether they conform to the Constitution.

The two judicial systems, federal and state, form layers of courts that check each other and are checked, in turn, by the law profession and the law schools that study the decisions and create an informed opinion.

The U.S. president appoints federal judges, but these appointments are subject to approval by the Senate. Once confirmed by the Senate, federal judges have appointments for life or until they choose to retire. Federal judges can be removed from their positions only if they are convicted of impeachable offenses by the Senate. The life-long appointments of federal judges make it easier for the judiciary to stay removed from political pressure. Similarly, the governors, the state legislatures, and the people select the state judges.

Supreme Court: The U.S. Supreme Court is the highest court of the country; it has ultimate judicial authority within the U.S. to interpret and decide questions of federal law, including the Constitution of the U.S. The Supreme Court is sometimes known by the acronyms SCOTUS and USSC (for U.S. Supreme Court).

It consists of 9 judges called justices, including a chief justice and 8 associate justices. As with all other federal judges, they are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. They also receive appointments for life, subject only to impeachment for serious crimes or improprieties.

Most of the Supreme Court cases are appeals from lower federal courts or from state courts, and a handful come from other parts of the Court’s jurisdiction. The Court typically issues written decisions in fewer than a hundred cases a year. All cases are heard and decided by the entire Court, except in rare cases when a justice chooses not to participate because of a conflict of interest or other potential prejudicial interest in a case.

Interesting to know: The Supreme Court didn’t have a building of its own till 1935. The U.S. Supreme Court building was designed by architect Cass Gilbert and built between 1932 and 1935. Marble for the court building was brought from Italy with personal assistance of Benito Mussolini.

Special Courts: Congress has established several courts to decide cases arising within its legislative powers. These are called legislative courts because they lie outside of the Constitution’s Article III. For example, the Court of Federal Claims hears cases of people who file claims against the government and seek money as a result. The Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces is the final appeals court for court-martial convictions in the armed forces. There is also a separate appeals court that deals with cases involving veterans’ benefits. The Tax Court tries and decides cases involving federal taxes, tax exemptions for charities, and other tax-related matters.

Administration: The judicial branch employs about 30,000 people, including judges, clerks, and other staff. The management and organization of the judicial workload is shared by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts and the Federal Judicial Center. In addition, standards for sentencing criminal offenders are established by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which is an independent agency.

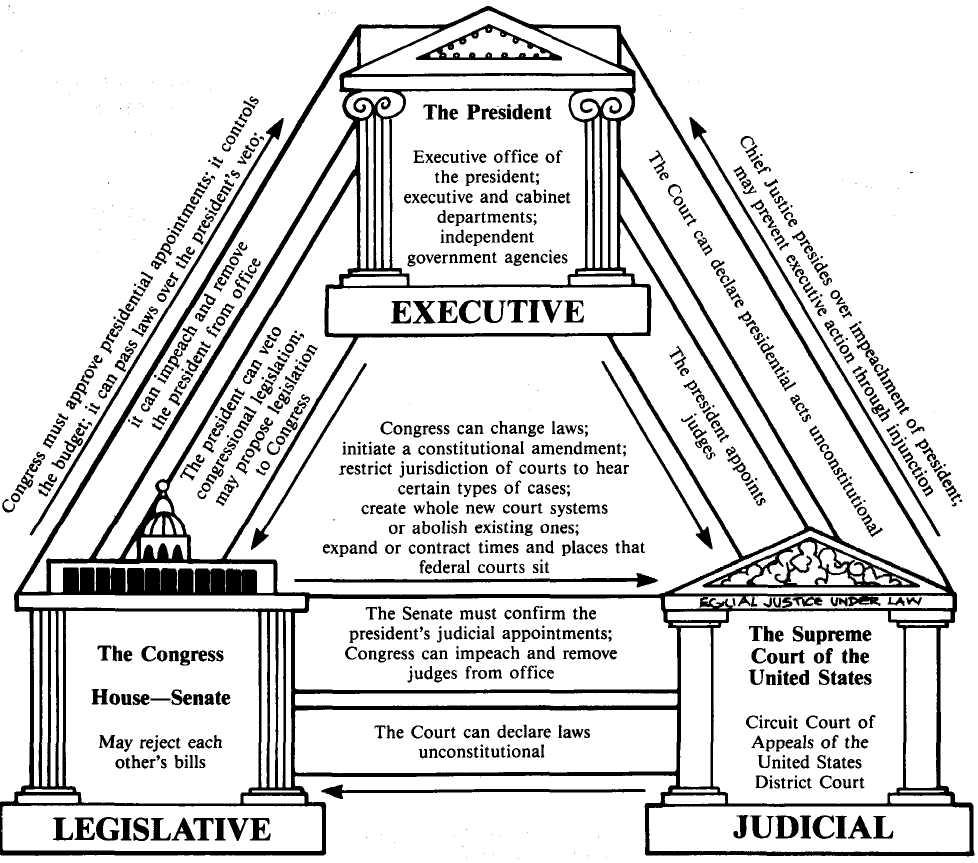

Separation of Powers and System of Checks and Balances

The division of government power among three separate but equal branches provides for a system of checks and balances. Each branch checks or limits the power of the other branches. For example, although Congress makes laws, the president can veto them. Even if the president vetoes a law, Congress may check the president by overriding his veto with a two-thirds vote. The Supreme Court can overturn laws passed by Congress and signed by the president. The selection of federal and Supreme Court judges is made by the other two branches. The president appoints judges, but the Senate reviews his candidates and has the power to reject his choices. With this system of checks and balances, no branch of government has a superior power.

Figure 8. System of checks and balances

Thus, by dividing power among the three branches of government, the Constitution effectively ensures that government power will not be usurped by a small powerful group or a few leaders.

However, there are other features of the political system, not mentioned in the Constitution, which directly and indirectly influence American politics.

Party System: Historically, 3 features have characterized the party system in the U.S.:

1) two major parties alternating in power;

2) lack of ideology; and

3) lack of unity and party discipline.

The U.S. has had only 2 major parties throughout its history. When the U.S. was founded, 2 strong political groupings emerged - the Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

Since then, the practice of two major parties alternating each other in power has existed. And for over one hundred years, America’s two-party system has been dominated by the Democratic and Republican Parties.

The Democratic Party was started in the 1820’s growing from an offshoot of the country’s first party, the Federalist Party.

The Republican Party began as an anti-slavery party in 1854 with members from the Democratic Party and the Whigs. It was formed to oppose the spread of slavery into new states.

Neither party, however, has ever completely dominated American politics. On the national level, the majority party in Congress has not always been the same as the party of the president. Even in the years when one party dominated national politics, the other party retained much support at state or local levels. Thus, the balance between the Democrats and Republicans has shifted back and forth. In general, the parties tend to be similar. Democrats and Republicans support the same overall political and economic goals. Neither party seeks to shake the foundation of the U.S. economy or social structure.