Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorder / Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorders, Two Volume Set - Volume 2 - M-Z - I

.pdf

Stickler syndrome

WEBSITES

“Sex-determining Region Y.” Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim

.cgi?id=480000 .

Carin Lea Beltz, MS

Steinert disease see Myotonic dystrophy

Stein-Leventhal syndrome see Polycystic ovary syndrome

I Stickler syndrome

Definition

Stickler syndrome is a disorder caused by a genetic malfunction in the tissue that connects bones, heart, eyes, and ears.

Description

Stickler syndrome, also known as hereditary arthroophthalmopathy, is a multisystem disorder that can affect the eyes and ears, skeleton and joints, and craniofacies. Symptoms may include myopia, cataract, and retinal detachment; hearing loss that is both conductive and sensorineural; midfacial underdevelopment and cleft palate; and mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia and/or arthritis. The collection of specific symptoms that make up the syndrome were first documented by Stickler et al., in a 1965 paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings titled “Hereditary Progressive ArthroOpthalmopathy.” The paper associated the syndrome’s sight deterioration and joint changes. Subsequent research has redefined Stickler syndrome to include other symptoms.

Genetic profile

Stickler syndrome is associated with mutations in three genes: COL2A1 (chromosomal locus 12q13), COL11A1 (chromosomal locus 1p21), and COL11A2 (chromosomal locus 6p21). It is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The majority of individuals with Stickler syndrome inherited the abnormal allele from a parent, and the prevalence of new gene mutations is unknown. Individuals with Stickler syndrome have a 50% chance of passing on the abnormal gene to each offspring.

The syndrome can manifest itself differently within families. If the molecular genetic basis of Stickler syndrome has been established, molecular genetic testing can be used for clarification of each family member’s genetic status and for prenatal testing.

A majority of cases are attributed to COL2A1 mutations. All COL2A1 mutations known to cause Stickler syndrome result in the formation of a premature termination codon within the type-II collagen gene. Mutations in COL11A1 have only recently been described, and COL11A2 mutations have been identified only in patients lacking ocular findings.

Although the syndrome is associated with mutations in the COL2A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2 genes, no linkage to any of these three known loci can be established in some rare cases with clinical findings consistent with Stickler syndrome. It is presumed that other, as yet unidentified, genes mutations also account for Stickler syndrome.

Genetically related disorders

There are a number of other phenotypes associated with mutations in COL2A1. Achondrogenesis type I is a fatal disorder characterized by absence of bone formation in the vertebral column, sacrum, and pubic bones, by the shortening of the limbs and trunk, and by prominent abdomen. Hypochondrogenesis is a milder variant of achondrogenesis. Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, a disorder with skeletal changes more severe than in Stickler syndrome, manifests in significant short stature, flat facial profile, myopia, and vitreoretinal degeneration. Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia Strudwick type is another skeletal disorder that manifests in severe short stature with severe protrusion of the sternum and scoliosis, cleft palate, and retinal detachment. A distinctive radiographic finding is irregular sclerotic changes, described as dappled, which are created by alternating zones of osteosclerosis and ostopenia in the metaphyses (ends) of the long bones. Spondyloperipheral dysplasia is a rare condition characterized by short stature and radiographic changes consistent with a spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia and brachydactyly. Kneist dysplasia is a disorder that manifests in disproportionate short stature, flat facial profile, myopia and vitreoretinal degeneration, cleft palate, backward and lateral curvature of the spine, and a variety of radiographic changes.

Other phenotypes associated with mutations in COL11A1 include Marshall syndrome, which manifests in ocular hypertelorism, hypoplasia of the maxilla and nasal bones, flat nasal bridge, and small upturned nasal tip. The flat facial profile of Marshall syndrome is usually evident into adulthood, unlike Stickler syndrome.

1094 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

Manifestations include radiographs demonstrating hypoplasia of the nasal sinuses and a thickened calvarium. Ocular manifestations include high myopia, fluid vitreous humor, and early onset cataracts. Sensorineural hearing loss is common and sometimes progressive. Cleft palate is seen both as isolated occurrence and as part of the Pierre-Robin sequence (micrognathia, cleft palate, and glossoptosis). Other manifestations include short stature and early onset arthritis, and skin manifestations that may include mild hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis.

Other phenotypes associated with mutations in COL11A2 include autosomal recessive oto-spondy- lometa-epiphyseal dysplasia, a disorder characterized by flat facial profile, cleft palate, and severe hearing loss. Anocular Stickler syndrome caused by COL11A2 mutations is close in similarity to this disorder. WeissenbachZweymuller syndrome has been characterized as neonatal Stickler syndrome but it is a separate entity from Stickler syndrome. Symptoms include midface hypoplasia with a flat nasal bridge, small upturned nasal tip, micrognathia, sensorineural hearing loss, and rhizomelic limb shortening. Radiographic findings include vertebral coronal clefts and dumbbell-shaped femora and humeri. Catch-up growth after age two or three is common and the skeletal findings become less apparent in later years.

Demographics

No studies have been done to determine Stickler syndrome prevalence. An approximate incidence of Stickler syndrome among newborns is estimated based on data on the incidence of Pierre-Robin sequence in newborns. One in 10,000 newborns have Pierre-Robin sequence, and 35% of these newborns subsequently develop signs or symptoms of Stickler syndrome. These data suggest that the incidence of Stickler syndrome among neonates is approximately one in 7,500.

Signs and symptoms

Stickler syndrome may affect the eyes and ears, skeleton and joints, and craniofacies. It may also be associated with coronary complications.

Ocular symptoms

Near-sightedness is a common symptom of Stickler syndrome. High myopia is detectable in newborns. Common problems also include astigmatism and cataracts. Risk of retinal detachment is higher than normal. Abnormalities of the vitreous humor, the colorless, transparent jelly that fills the eyeball, are also observed. Type 1, the more common vitreous abnormality, is characterized by a persistence of a vestigial vitreous gel in the space behind the lens, and is bordered by a folded mem-

K E Y T E R M S

Cleft palate—A congenital malformation in which there is an abnormal opening in the roof of the mouth that allows the nasal passages and the mouth to be improperly connected.

Dysplasia—The abnormal growth or development of a tissue or organ.

Glossoptosis—Downward displacement or retraction of the tongue.

Micrognathia—Small lower jaw with recession of lower chin.

Mitral valve prolapse—A heart defect in which one of the valves of the heart (which normally controls blood flow) becomes floppy. Mitral valve prolapse may be detected as a heart murmur but there are usually no symptoms.

Otitis media—Inflammation of the middle ear, often due to fluid accumulation secondary to an infection.

Phenotype—The physical expression of an individuals genes.

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia—Abnormality of the vertebra and epiphyseal centers that causes a short trunk.

brane. Type 2, which is much less common, is characterized by sparse and irregularly thickened bundles throughout the vitreous cavity. These vitreous abnormalities can cause sight deterioration.

Auditory symptoms

Hearing impairment is common, and some degree of sensorineural hearing loss is found in 40% of patients. The degree of hearing impairment is variable, however, and may be progressive. Typically, the impairment is high tone and often subtle. Conductive hearing loss is also possible. It is known that the impairment is related to the expression of type II and IX collagen in the inner ear, but the exact mechanism for it is unclear. Hearing impairment may be secondary to the recurrent ear infections often associated with cleft palate, or it may be secondary to a disorder of the ossicles of the middle ear.

Skeletal symptoms

Skeletal manifestations are short stature relative to unaffected siblings, early-onset arthritis, and abnormalities at ends of long bones and vertebrae. Radiographic

syndrome Stickler

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

1095 |

Stickler syndrome

findings consistent with mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. Some individuals have a physique similar to Marfan syndrome, but without tall stature. Young patients may exhibit joint laxity but it diminishes or even resolves completely with age. Early-onset arthritis is common and generally mild, mostly resulting in joint stiffness. Arthritis is sometimes severe, leading to joint replacement as early as the third or fourth decade.

Craniofacial findings

Several facial features are common with Stickler syndrome. A flat facial profile referred to as a “scooped out” face results from underdevelopment of the maxilla and nasal bridge, which can cause telecanthus and epicanthal folds. Flat cheeks, flat nasal bridge, small upper jaw, pronounced upper lip groove, small lower jaw, and palate abnormalities are possible, all in varying degrees. The nasal tip may be small and upturned, making the groove in the middle of the upper lip appear long. Micrognathia is common and may compromise the upper airway, necessitating tracheostomy. Midfacial hypoplasia is most pronounced in infants and young children, and older individuals may have a normal facial profile.

Coronary findings

Mitral valve prolapse may be associated with Stickler syndrome, but studies are, as yet, inconclusive about the connection.

Diagnosis

Stickler is believed to be a common syndrome in the United States and Europe, but only a fraction of cases are diagnosed since most patients have minor symptoms. Misdiagnosis may also occur because symptoms are not correlated as having a single cause. More than half of patients with Stickler syndrome are originally misdiagnosed according to one study.

While the diagnosis of Stickler syndrome is clinically based, clinical diagnostic criteria have not been established. Patients usually do not have all symptoms attributed to Stickler syndrome. The disorder should be considered in individuals with clinical findings in two or more of the following categories:

•Ophthalmologic. Congenital or early-onset cataract, myopia greater than -3 diopters, congenital vitreous anomaly, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Normal newborns are typically hyperopic (+1 diopter or greater), and so any degree of myopia in an at-risk newborn, such as one with Pierre-Robin sequence or an affected parent, is suggestive of the diagnosis of Stickler syndrome. Less common ophthalmological

symptoms include paravascular pigmented lattice degeneration and cataracts.

•Craniofacial. Midface hypoplasia, depressed nasal bridge in childhood, anteverted nares (tipped or bent nasal cavity openings), split uvula, cleft hard palate, micrognathia, Pierre-Robin sequence.

•Audiologic. Sensorineural hearing loss.

•Joint. Hypermobility, mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, precocious osteoarthritis.

It is appropriate to evaluate at-risk family members with a medical history and physical examination and ophthalmologic, audiologic, and radiographic assessments. Childhood photographs may be helpful in the evaluation of adults since craniofacial findings may become less distinctive with age.

Molecular genetic testing

Mutation analysis for COL2A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2 is available. Detection is performed by mutation scanning of the coding sequences. Stickler syndrome has been associated with stop mutations in COL2A1 and with missense and splicing mutations in all of the three genes. Because the meaning of a specific missense mutation within the gene coding sequence may not be clear, mutation detection in a parent is not advised without strong clinical support for the diagnosis.

Clinical findings can influence the order for testing the three genes. In patients with ocular findings, including type 1 congenital vitreous abnormality and mild hearing loss, COL2A1 may be tested first. In patients with typical ocular findings including type 2 congenital vitreous anomaly and significant hearing loss, COL11A1 may be tested first. In patients with hearing loss and craniofacial and joint manifestations but without ocular findings, COL11A2 may be tested first.

Prenatal testing

Before considering prenatal testing, its availability must be confirmed and prior testing of family members is usually necessary. Prenatal molecular genetic testing is not usually offered in the absence of a known disease-causing mutation in a parent. For fetuses at 50% risk for Stickler syndrome, a number of options for prenatal testing may exist. If an affected parent has a mutation in the gene COL2A1 or COL11A1, molecular genetic testing may be performed on cells obtained by chorionic villus sampling at 10–12 weeks gestation or amniocentesis at 16–18 weeks gestation. Alternatively, or in conjunction with molecular genetic testing, ultrasound examination can be performed at 19–20 weeks gestation to detect cleft palate. For fetuses with no known family history of Stickler syn-

1096 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

drome in which cleft palate is detected, a three-generation pedigree may be obtained, and relatives who have findings suggestive of Stickler syndrome should be evaluated.

Treatment and management

Individuals diagnosed with Stickler syndrome, and individuals in whom the diagnosis cannot be excluded, should be followed for potential complications.

Evaluation by an ophthalmologist familiar with the ocular manifestations of Stickler syndrome is recommended. Individuals with known ocular complications may prefer to be followed by a vitreoretinal specialist. Patients should avoid activities that may lead to traumatic retinal detachment, such as contact sports. Patients should be advised of the symptoms associated with a retinal detachment and the need for immediate evaluation and treatment when such symptoms occur. Individuals from families with Stickler syndrome and a known COL2A1 or COL11A1 mutation who have not inherited the mutant allele do not need close ophthalmologic evaluation.

A baseline audiogram to test hearing should be performed when the diagnosis of Stickler syndrome is suspected. Follow-up audiologic evaluations are recommended in affected persons since hearing loss can be progressive.

Radiological examination may detect signs of mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. Treatment is symptomatic, and includes over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications before and after physical activity. No preventative therapies currently exist to minimize joint damage in affected individuals. In an effort to delay the onset of arthropathy, physicians may recommend avoiding physical activities that involve high impact to the joints, but no data support this recommendation.

Infants with Pierre-Robin sequence need immediate attention from otolaryngology and pediatric critical care specialists. Evaluation and management in a comprehensive craniofacial clinic that provides all the necessary services, including otolaryngology, plastic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, pediatric dentistry, and orthodontics is recommended. Tracheostomy may be required, which involves placing a tube in the neck to facilitate breathing.

Middle ear infections may be a recurrent problem secondary to the palatal abnormalities, and ear tubes may be required. Micrognathia (small jaw) tends to become less prominent over time in most patients, allowing for removal of the tracheostomy. In some patients, however, significant micrognathia persists and causes orthodontic problems. In these patients, a mandibular advancement procedure may be required to correct jaw misalignment.

Cardiac care is recommended if complaints suggestive of mitral valve prolapse, such as episodic tachycardia and chest pain, are present. While the prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in Stickler syndrome is unclear, all affected individuals should be screened since individuals with this disorder need antibiotic prophylaxis for certain surgical procedures.

Prognosis

Prognosis is good under physician care. It is particularly important to receive regular vision and hearing exams. If retinal detachment is a risk, it may be advisable to avoid contact sports. Some craniofacial symptoms may improve with age.

Resources

PERIODICALS

Bowling, E. L., M. D, Brown, and T. V. Trundle. “The Stickler Syndrome: Case Reports and Literature Review.” Optometry 71 (March 2000): 177 .

MacDonald, M. R., et al. “Reports on the Stickler Syndrome, An Autosomal Connective Tissue Disorder.” Ear, Nose & Throat Journal 76 (October 1997): 706.

Snead, M. P., and J. R. Yates. “Clinical and Molecular Genetics of Stickler Syndrome.” Journal of Medical Genetics 36 (May 1999): 353 .

Wilkin, D. J., et al. “Rapid Determination of COL2A1 Mutations in Individuals with Stickler Syndrome: Analysis of Potential Premature Termination Codons.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 11 (September 2000): 141 .

ORGANIZATIONS

Stickler Involved People. 15 Angelina, Augusta, KS 67010. (316) 775-2993. http://www.sticklers.org .

Stickler Syndrome Support Group. PO Box 371, Walton-on- Thames, Surrey KT12 2YS, England. 44-01932 267635.http://www.stickler.org.uk .

WEBSITES

Robin, Nathaniel H., and Matthew L. Warman. “Stickler

Syndrome.” GeneClinics. University of Washington,

Seattle. http://www.geneclinics.org/profiles/stickler .

“Stickler Syndrome.” NORD—National Organization for Rare Disorders. http://www.rarediseases.org .

Jennifer F. Wilson, MS

I Stomach cancer

Definition

Stomach cancer (also known as gastric cancer) is a disease in which the cells forming the inner lining of the

cancer Stomach

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

1097 |

Stomach cancer

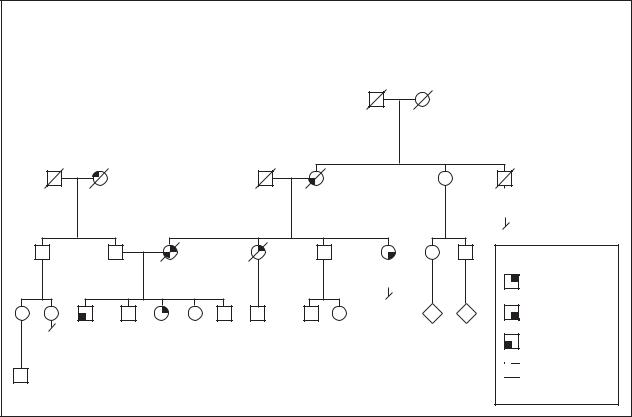

Gastric Cancer

Autosomal Dominant / Familial

|

|

|

|

|

German |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Died young |

d.65y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

of unknown |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cancer |

|

|

|

|

Italian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d.65y |

|

d.79y |

d.51y |

|

|

71y |

d.21y |

|

Lung cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

War-related |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

4 |

Key: |

61y |

52y |

dx.40y |

d.32y |

39y |

dx.29y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

d.47y |

|

|

32y |

|

|

Colon cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

N |

Stomach cancer |

25y |

21y |

17y |

16y |

11y |

6y |

12y |

10y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liver cancer |

Lung cancer dx = Diagnosed

Lung cancer dx = Diagnosed

(Gale Group)

stomach become abnormal and start to divide uncontrollably, forming a mass or a tumor.

Description

The stomach is a J-shaped organ that lies in the abdomen, on the left side. The esophagus (or the food pipe) carries the food from the mouth to the stomach. The stomach produces many digestive juices and acids that mix with the food and aid in the process of digestion. The stomach is divided into five sections. The first three are together referred to as the proximal stomach, and produce acids and digestive juices, such as pepsin. The fourth section of the stomach is where the food is mixed with the gastric juices. The fifth section of the stomach acts as a valve and controls the emptying of the stomach contents into the small intestine. The fourth and the fifth sections together are referred to as the distal stomach. Cancer can develop in any of the five sections of the stomach. The symptoms and the outcomes of the disease may vary depending on the location of the cancer.

In many cases, the cause of the stomach cancer is unknown. Several environmental factors have been linked to stomach cancer. Consuming large amounts of

smoked, salted, or pickled foods has been linked to increased stomach cancer risk. Nitrates and nitrites, chemicals found in some foods such as cured meats may be linked to stomach cancer as well.

Infection by the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacterium has been found more often in people with stomach cancer. H. pylori can cause irritation of the stomach lining (chronic atrophic gastritis), which may lead to precancerous changes of the stomach cells.

People who have had previous stomach surgery for ulcers or other conditions may have a higher likelihood of developing stomach cancers, although this is not certain. Another risk factor is developing polyps, benign growths in the lining of the stomach. Although polyps are not cancerous, some may have the potential to turn cancerous.

While no particular gene for stomach cancer has yet been identified, people with blood relatives who have been diagnosed with stomach cancer are more likely to develop the disease. In addition, people who have inherited disorders such as familial adenomatous polyps (FAP) and Lynch syndrome have an increased risk for stomach cancer. For unknown reasons, stomach cancers occur more frequently in people with the blood group A.

1098 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

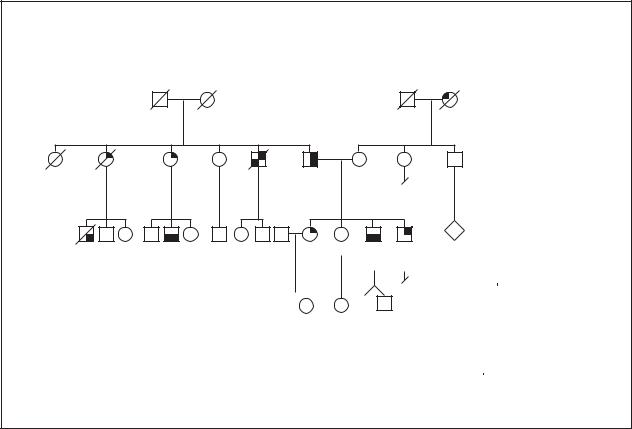

Gastric Cancer

Autosomal Dominant / Familial

Japanese |

South African |

||

d.81y |

d.49y |

d.74y |

d.72y |

|

Unknown causes |

Heart attack |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

d.16y |

dx.50y |

dx.50y |

62y |

dx.46y dx.39y |

50y |

|

Car |

d.51y |

64y |

|

d.49y |

55y |

|

accident |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

N |

dx.38y |

dx.28y |

dx.30y |

30y dx.28y dx.26y |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

d.41y |

32y |

31y |

|

28y |

27y |

Key: |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colon cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9y |

7y |

7y |

5y |

|

|

|

|

Stomach cancer |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pancreatic cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Breast cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

dx = Diagnosed |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Gale Group)

Genetic profile

Although environmental or health factors may explain frequent occurrences of stomach cancer in families, it is known that inherited risk factors also exist. Some studies show close relatives having an increased risk of stomach cancer two to three times that of the general population. Interestingly, an earlier age at the time of stomach cancer diagnosis may be more strongly linked to familial stomach cancer. Two Italian studies estimated that about 8% of stomach cancer is due to inherited factors. Some of these hereditary factors are known genetic conditions while in other instances, the factors are unknown.

Familial cancer syndromes are hereditary conditions in which specific types of cancer, and perhaps other features, are consistently occurring in affected individuals. Familial adenomatosis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) are familial cancer syndromes that increase the risk of colon cancer.

FAP is due to changes in the APC gene. Individuals with FAP typically have more than 100 polyps, mush- room-like growths, in the digestive system as well as

other effects. Polyps are noncancerous growths that have the potential to become cancerous if not removed. At least one study estimated that the risk of stomach cancer was seven times greater for individuals with FAP than the general population.

The number of polyps present is an important distinction between FAP and HNPCC. Polyps do not form at such a high rate in HNPCC but individuals with this condition are still at increased risk of colon, gastric, and other cancers. At least five genes are known to cause HNPCC, but alterations in the hMSH2 or hMLH1 genes have been found in the majority of HNPCC families.

Other inherited conditions such as Peutz-Jeghers, Cowden and Li-Fraumeni syndromes and other syndromes have been associated with stomach cancer. All of these syndromes have distinct features beyond stomach cancer that aid in identifying the specific syndrome. The inheritance pattern for most of these syndromes is dominant, meaning only one copy of the gene needs to be inherited for the syndrome to be present.

In 1999, the First Workshop of the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium developed criteria for defining hereditary stomach cancer not due to

cancer Stomach

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

1099 |

known genetic conditions, such as those listed above. In areas with low rates of stomach cancer, hereditary stomach cancer was defined according to the Consortium as: (1) families with two or more cases of stomach cancer in first or second degree relatives (siblings, parents, children, grandparents, nieces/nephews or aunts/uncles) with at least one case diagnosed before age 50 or (2) three or more cases at any age. In countries with higher rates of stomach cancer, such as Japan, the suggested criteria are: (1) at least three affected first degree relatives (sibling, children or parents) and one should be the first degree relative of the other two; (2) at least two generations (without a break) should be affected; and (3) at least one cancer should have occurred before age 50.

Inherited changes in the E-Cadherin/CDH1 gene first were reported in three families of native New Zealander (Maori) descent with stomach cancer and later were found in families of other ancestry. The E- Cadherin/CDH1 gene, which plays a role in cell to cell connection, is located on chromosome 16 at 16q22. The percentage of hereditary stomach cancer that is due to E- Cadherin/CDH1 gene alterations is uncertain. In summary, most stomach cancer is due to environmental or other non-genetic causes. A small portion of cancer of the stomach, about 8%, is due to inherited factors one of which is E-Cadherin/CDH1 gene alterations.

Demographics

The American Cancer Society estimates, based on previous data from the National Cancer Institute and the United States Census, that 21,700 Americans will be diagnosed with stomach cancer during 2001. In some areas, nearly twice as many men are affected by stomach cancer than women. Most cases of stomach cancer are diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 70 but in families with a hereditary risk of stomach cancer, younger cases are more frequently seen. Stomach cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer deaths in many areas of the world, most notably Japan, but the number of new stomach cancer cases is decreasing in some areas, especially in developed countries. In the United States, the use of refrigerated foods and increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, instead of preserved foods, may be a reason for the decline in stomach cancer.

Signs and symptoms

Stomach cancer can be difficult to detect at early stages since symptoms are uncommon and frequently unspecific. The following can be symptoms of stomach cancer:

An excised specimen of a human stomach showing a cancerous tumor (triangular shaped). (Custom Medical Stock Photo, Inc.)

•poor appetite or weight loss

•fullness even after a small meal

•abdominal pain

•heart burn, belching, indigestion or nausea

•vomiting, with or without blood

•swelling or problems with the abdomen

•anemia or blood on stool (feces) examination

Diagnosis

In addition to a physical examination and fecal occult blood testing (checking for blood in the stool), special procedures are done to evaluate the digestive system including the esophagus, stomach, and upper intestine. Procedures used to diagnose stomach cancer include: barium upper gastrointestinal (GI) x rays, upper endoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Genetic testing can also be used to determine an individuals predisposition to stomach cancer.

Upper GI x rays

The first step in evaluation for stomach cancer may be x ray studies of the esophagus, stomach, and upper intestine. This type of study requires drinking a solution with barium to coat the stomach and other structures for easier viewing. Air is sometimes pumped into the stomach to help identify early tumors.

cancer Stomach

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

1101 |

Stomach cancer

Upper endoscopy

Endoscopy allows a diagnosis in about 95% of cases. In upper endoscopy, a small tube, an endoscope, is placed down the throat so that the esophagus, stomach, and upper small intestine can be viewed. If a suspicious area is seen, a small sample of tissue, a biopsy, is taken. The tissue from these samples can be examined for evidence of cancer.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound allows several layers to be seen and so it is useful in determining where cancer may have spread. With this test, an endoscope is placed into the stomach and sound waves are emitted. A machine analyzes the sound waves to see differences in the tissues in order to identify tumors.

Genetic testing

If a certain genetic syndrome such as FAP or HNPCC is suspected, genetic testing may be available either through a clinical laboratory or through a research study. As of 2001, testing for E-cadherin/CDH1 gene alterations is mainly available through research studies. Once an E-cadherin/CDH1 gene change is identified through research, the results can be confirmed through a certified laboratory.

When a gene change is identified, genetic testing may be available for other family members. For most genetic tests, it is helpful to test the affected individual first, since they are most likely to have a gene change. Genetic testing is usually recommended for consenting adults, however, for syndromes in which stomach cancer is a common feature, testing of children may be reasonable for possible prevention of health problems.

The detection rate and usefulness of genetic testing depends on the genetic syndrome. If genetic testing is under consideration, a detailed discussion with a knowledgeable physican, genetic counselor, or other practitioner is helpful in understanding the advantages and disadvantages of the genetic test. It is also important to realize that testing positive for the E-cadherin/CDH1 gene does not necessarily mean the individual will be affected with cancer. However, they may have an increased risk compared to an individual without the gene.

Treatment and management

Regular mass screening for stomach cancer has not been found useful in areas, such as the United States, where stomach cancer is less common. When stomach cancer is diagnosed in the United States, it is usually discovered at later, less curable stages. However, individuals with an increased risk of stomach cancer, including those

with a known genetic syndrome or with a family history of the disease, may consider regular screening before the development of cancer. If a known hereditary cancer syndrome is suspected, screening should follow the generally accepted guidelines for these conditions.

In 1999, the First Workshop of the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium recommended that regular detailed upper endocopy and biopsy be done in families with hereditary stomach cancer, including screening every six to 12 months for individuals with known E-cadherin gene alterations, if no other treatment has been done. Some individuals with a known hereditary stomach cancer risk have surgery to remove the stomach prior to development of any stomach cancer, but the effectiveness of this prevention strategy is uncertain. Several other less drastic prevention measures have been considered including changes in diet, use of vitamins, and antibiotic treatment of H. pylori. The American Cancer Society recommends limiting use of alcohol and tobacco.

Treatment of stomach cancer, in nearly all cases, involves some surgery. The amount of the stomach or surrounding organs that is removed depends on the size and location of the cancer. Sometimes, surgery is performed to try to remove all of the cancer in hopes of a cure while other times, surgery is done to relieve symptoms. Possible side effects of stomach surgery include leaking, bleeding, changes in diet, vitamin deficiencies, and other complications.

Chemotherapy involves administering anti-cancer drugs either intravenously (through a vein in the arm) or orally (in the form of pills). This can either be used as the primary mode of treatment or after surgery to destroy any cancerous cells that may have migrated to distant sites. Side effects (usually temporary) of chemotherapy may include low blood counts, hair loss, vomiting, and other symptoms.

Radiation therapy is often used after surgery to destroy the cancer cells that may not have been completely removed during surgery. Generally, to treat stomach cancer, external beam radiation therapy is used. In this procedure, high-energy rays from a machine that is outside of the body are concentrated on the area of the tumor. In the advanced stages of stomach cancer, radiation therapy is used to ease the symptoms such as pain and bleeding.

Prognosis

“Staging” is a method of describing cancer development. There are five stages in stomach cancer with stage 0 being the earliest cancer that has not spread while stage IV includes cancer that has spread to other organs.

1102 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

Expected survival rate can be roughly estimated based on the stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis.

The prognosis for patients with early stage cancer depends on the location of the cancer. When cancer is in the proximal part of the stomach, only 10-15% of people survive five years or more, even if they have been diagnosed with early stage cancer. For cancer that is in the distal part of the stomach, if it is detected at an early stage, the outlook is somewhat better. About 50% of the people survive for at least five years or more after initial diagnosis. However, only 20% of the patients are diagnosed at an early stage. Chance of survival depends on many factors and it is difficult to predict survival for a particular individual.

Resources

BOOKS

Flanders, Tamar, et al. “Cancers of the Digestive System.” In

Inherited Susceptibility: Clinical, Predictive and Ethical

Perspectives, edited by William D. Foulkes and Shirley V. Hodgson. Cambridge University Press, 1998. pp.158-165.

Lawrence, Walter, Jr. “Gastric Cancer.” In Clinical Oncology Textbook, edited by Raymond E. Lenhard, Jr., et al. American Cancer Society, 2000, pp.345-360.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Cancer Society. 1599 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta, Georgia 30329. (800) 227-2345. http://www.cancer

.org .

National Cancer Institute. Office of Communications, 31 Center Dr. MSC 2580, Bldg. 1 Room 10A16, Bethesda MD 20892-2580. (800) 422-6237. http://www.nci.nih

.gov .

WEBSITES

CancerBACUP. http://www.cancerbacup.org.uk .

Oncolink. University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center.

http://cancer.med.upenn.edu .

STOMACH-ONC. http://www.listserv.acor.org/archives/

stomach-org.html .

Kristin Baker Niendorf, MS, CGC

I Sturge-Weber syndrome

Definition

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SRS) is a condition involving specific brain changes that often cause seizures and mental delays. It also includes port-wine colored birthmarks (or “port-wine stains”), usually found on the face.

K E Y T E R M S

Calcification—A process in which tissue becomes hardened due to calcium deposits.

Choroid—A vascular membrane that covers the back of the eye between the retina and the sclera and serves to nourish the retina and absorb scattered light.

Computed tomography (CT) scan—An imaging procedure that produces a three-dimensional picture of organs or structures inside the body, such as the brain.

Glaucoma—An increase in the fluid eye pressure, eventually leading to damage of the optic nerve and ongoing visual loss.

Leptomeningeal angioma—A swelling of the tissue or membrane surrounding the brain and spinal cord, which can enlarge with time.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—A technique that employs magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of internal body structures and organs, including the brain.

Port-wine stain—Dark-red birthmarks seen on the skin, named after the color of the dessert wine.

Sclera—The tough white membrane that forms the outer layer of the eyeball.

Description

The brain finding in SRS is leptomeningeal angioma, which is a swelling of the tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord. These angiomas cause seizures in approximately 90% of people with SWS. A large number of affected individuals are also mentally delayed.

Port-wine stains are present at birth. They can be quite large, and are typically found on the face near the eyes or on the eyelids. Vision problems are common, especially if a port-wine stain covers the eyes. These vision problems can include glaucoma and vision loss.

Facial features, such as port-wine stains, can be very challenging for individuals with SWS. These birthmarks can increase in size with time, and this may be particularly emotionally distressing for the individuals, as well as their parents. A state of unhappiness about this is more common during middle childhood and later than it is at younger ages.

syndrome Weber-Sturge

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

1103 |

Sturge-Weber syndrome

This magnetic resonance image of the brain shows a patient affected with Sturge-Weber syndrome. The front of the brain is at the top. Green colored areas indicate fluidfilled ventricles. The blue area is where the brain has become calcified. (Photo Researchers, Inc.)

Genetic profile

The genetics behind Sturge-Weber syndrome are still unknown. Interestingly, in other genetic conditions involving changes in the skin and brain (such as neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis) the genetic causes are well described. It is known that most people with SRS are the only ones in their family with the condition; there is usually not a strong family history of the disease. However, as of 2001 a gene known to cause SRS is still not known. For now, SRS is thought to be caused by a random, sporadic event.

Demographics

Sturge-Weber syndrome is a sporadic disease that is found throughout the world, affecting males and females equally. The total number of people with Sturge-Weber syndrome is not known, but estimates range between one in 400,000 to one in 40,000.

Signs and symptoms

People with SWS may have a larger head circumference (measurement around the head) than usual. Leptomeningeal angiomas can progress with time. They usually only occur on one side of the brain, but can exist on both sides in up to 30% of people with SWS. The angiomas can also cause great changes within the brain’s

white matter. Generalized wasting, or regression, of portions of the brain can result from large angiomas. Calcification of the portions of the brain underlying the angiomas can also occur. The larger and more involved the angiomas are, the greater the expected amount of mental delays in the individual. Seizures are common in SWS, and they can often begin in very early childhood. Occasionally, slight paralysis affecting one side of the body may occur.

Port-wine stains are actually capillaries (blood vessels) that reach the skin’s surface and grow larger than usual. As mentioned earlier, the birthmarks mostly occur near the eyes; they often occur only on one side of the face. Though they can increase in size over time, portwine stains cause no direct health problems for the person with SWS.

Vision loss and other complications are common in SWS. The choroid of the eye can swell, and this may lead to increased pressure within the eye in 33-50% of people with SWS. Glaucoma is another common vision problem seen in SWS, and is more often seen when a person has a port-wine stain that is near or touches the eye.

In a 2000 study about the psychological functioning of children with SRS, it was noted that parents and teachers report a higher incidence of social problems, emotional distress, and problems with compliance in these individuals. Taking the mental delays into account, behaviors associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were noted; as it turns out, about 22% of people with SWS are eventually diagnosed with ADHD.

Diagnosis

Because no genetic testing is available for SturgeWeber syndrome, all diagnoses are made through a careful physical examination and study of a person’s medical history.

Port-wine stains are present at birth, and seizures may occur in early childhood. If an individual has both of these features, SWS should be suspected. A brain MRI or CT scan can often reveal a leptomeningeal angioma, brain calcifications, as well as any other associated white matter changes.

Treatment and management

Treatment of seizures in SWS by anti-epileptic medications is often an effective way to control them. In the rare occasion that an aggressive seizure medication therapy is not effective, surgery may be necessary. The general goal of the surgery is to remove the portion of brain that is causing the seizures, while keeping the normal brain tissue intact. Though most patients with SWS only have brain

1104 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |