Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorder / Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorders, Two Volume Set - Volume 2 - M-Z - I

.pdf

Van der Woude syndrome

KEY TERMS

Autosomal dominant—A pattern of genetic inheritance where only one abnormal gene is needed to display the trait or disease.

Cleft—An elongated opening or slit in an organ.

Genetic test—Testing of chromosomes and genes from an individual or unborn baby for a genetic condition. Genetic testing can only be done if the gene is known.

Palate—The roof of the mouth.

Ultrasound examination—Visualizing the unborn baby while it is still inside the uterus.

Demographics

Van der Woude syndrome is a rare condition. Estimates of its incidence range from one in every 35,000 to one in every 200,000 live births. Males and females are affected equally.

Signs and symptoms

The primary symptom associated with VWS is the development of pits near the center of the lower lip (present in more than 80% of cases). In addition, 60–70% of individuals with VWS also have cleft lip and/or cleft palate. A few individuals (about 10–20%) with VWS are missing teeth, most commonly the second incisors and the second molars.

Diagnosis

As of 2001, diagnosis of VWS relies solely upon physical examination and whether or not the characteristic features of VWS are present or absent. The family history may also have an important role in determining the diagnosis. For example, if lower lip pits and a cleft palate are present in a newborn and no popliteal webs or other feature of PPS is present, then the child has VWS. If a newborn is born with a cleft palate only but has a family history of VWS, then the child most likely has inherited VWS.

As cleft lip and/or palate occurs in other genetic conditions as well as by itself, a newborn with this birth defect needs to be fully evaluated to ensure that the reason for the cleft is correctly determined. Likewise, lower lip pits may be seen in VWS, in PPS and rarely, in a third genetic condition called orofaciodigital syndrome, type 1; consequently, a baby born with lower lips pits needs to be fully evaluated.

Prenatal diagnosis for VWS can be attempted through ultrasound examination of unborn babies at risk for the condition. Cleft lip and very rarely cleft palate can be identified on ultrasound examination. However, as some clefts are small and some individuals with VWS do not have clefts at all, a normal ultrasound examination cannot completely rule out the chance the baby has inherited VWS. An ultrasound examination with high resolution, or a level 2 ultrasound, and an experienced technician may increase the chance of seeing cleft lips or palate. Lip pits cannot be seen on ultrasound examination, even with a higher resolution ultrasound. As of 2001, genetic testing of the unborn baby is not available as the gene(s) causing VWS have not been identified.

Treatment and management

An individual with VWS will be treated and followed according to the features he or she has developed. The lip pits seen in VWS rarely cause problems. Occasionally, saliva may ooze from the pits and if so, a fistula may have developed. A fistula is an abnormal passageway or opening that develops, and in VWS, a fistula may develop between a salivary gland located under the lip and the lip surface. The pits and fistulas may be surgically removed.

If a cleft lip and/or palate is present, surgery will be necessary to correct this problem. The treatment and management of cleft lips and palates in individuals with VWS is no different from cleft lips and palates occurring in other genetic conditions or by themselves. The child will need to be followed closely for ear and sinus infections and hearing problems. The child may need speech therapy and should be followed by a dentist and orthodontist. Counseling may be needed as the child grows up to address any concerns about speech and/or appearance.

Prognosis

Overall, individuals with VWS do well. If a cleft lip and/or palate is present at birth, there may be some feeding difficulties in the newborn period and in the following 3 to 6 months, until the cleft is corrected. However, once surgery repairing the cleft is completed, the child typically does well. Van der Woude syndrome is not associated with a shorter lifespan.

Resources

PERIODICALS

Nagore, Eduardo, et al. “Congenital Lower Lip Pits (Van der Woude Syndrome): Presentation of 10 Cases.” Pediatric Dermatology 15, no. 6 (November/December 1998): 443–445.

1168 |

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

Rivkin, C.J., et al. “Dental Care for the Patient with a Cleft Lip and Palate. Part 1: From Birth to the Mixed Dentition Stage.” British Dental Journal 188, no. 2 (January 22, 2000): 78–83.

ORGANIZATIONS

AboutFace USA. PO Box 458, Crystal Lake, IL 60014. (312) 337-0742 or (888) 486-1209. aboutface2000@aol.com.http://www.aboutface2000.org .

Family Village. Waisman Center, University of WisconsinMadison, 1500 Highland Ave., Madison, WI 53705-2280. familyvillage@waisman.wisc.edu.

http://www.familyvillage.wisc.edu/index.html . WideSmiles. PO Box 5153, Stockton, CA 95205-0153. (209)

942-2812. http://www.widesmiles.org .

Cindy L. Hunter, CGC

I VATER association

Definition

VATER association describes a pattern of related birth defects in the same infant involving three or more of the following: vertebrae (spine), anus and rectum, heart, trachea (windpipe), esophagus, radius (bone of the arm), and kidneys. Infants can have any combination of features and there is a wide range of severity. Survival and medical complications depend on the extent and severity of features in each case.

Description

Quan and Smith first developed the term VATER association in 1973 to describe a similar pattern of birth defects in more than one infant. The problems at birth did not represent a certain syndrome but appeared to be associated since they were present in several babies. VATER is an acronym or abbreviation representing the first letter of each feature in the association: Vertebral (spine) abnormalities, Anal atresia (partial absence of the anus or unusual connection between anus and rectum), Tracheo- Esophageal fistula (connection between the windpipe and the tube carrying food from mouth to stomach), and Radial (bone of the forearm) or Renal (kidney) differences.

In the 1970s some researchers expanded the VATER abbreviation to VACTERL. It was expanded to include cardiac (heart) abnormalities, and limb differences in general (differences in the arms and hands). In the expanded VACTERL, “L” includes radial differences and “R” represents kidney differences only. Both VATER and

VACTERL are used to describe the same association of birth defects.

The exact cause of VATER is unknown. This is because VATER is rare and because the features vary from patient to patient. Many researchers agree that the cause of VATER occurs very early in the development of the embryo in order to affect so many organ systems. It is unknown whether VATER has a single cause or multiple causes during this early development process.

In the first couple of weeks after conception, a human embryo is a clump of cells that are unspecialized and full of potential. In the third week of pregnancy the embryo undergoes a process called gastrulation. This is when the cells of the embryo begin to group together in different areas. The different cell groups begin to specialize and prepare to form different organs and body parts. The mesoderm is the group of cells that organizes and eventually forms the baby’s bones, muscles, heart, blood, kidneys, and reproductive organs. In the third week of pregnancy, the notochord also develops. The notochord is the future spinal cord and gives the early embryo a center and stability. It may also have a role in organizing other cell groups. The primitive gut also organizes in the fourth week. The primitive gut undergoes more specialization and division into zones called the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The esophagus (tube from mouth to stomach) and trachea (windpipe) develop from the foregut. The anus and rectum develop from the hindgut. The constant cell movement, grouping, and specialization is a precise process. Any interruption or damage in this early stage can affect multiple organs and body structures.

Some researchers believe the cause of VATER is a problem with gastrulation. Other researchers believe the error occurs when mesoderm cells begin to move to areas to begin specialization. Another theory is that the mesoderm receives abnormal signals and becomes disorganized. Other researchers believe more than one error occurs in more than one area of the early embryo to produce VATER. Some also believe an abnormality of the notochord is involved in the development of VATER.

One group of researchers has discovered that pregnant rats that are given a toxic drug called adriamycin have offspring with birth defects very similar to those seen in humans with VATER. This has allowed the researchers to study normal and abnormal development of the early embryo. The study of rats showed abnormal notochord development in offspring with connections of the trachea and esophagus. In those offspring, the notochord was thickened and connected unusually to the foregut. More research of this animal model will answer many questions about the development and cause of the features of VATER.

association VATER

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

1169 |

VATER association

KEY TERMS

Anus—The opening at the end of the intestine that carries waste out of the body

Fistula—An abnormal passage or communication between two different organs or surfaces.

Genetic profile

The exact genetic cause of VATER association is unknown. Most cases are sporadic and do not occur more than once in the same family. This was determined by studies of families with an affected individual. Since cases are rare and most are isolated in a family, studies to find a genetic cause have been unsuccessful. Parents of a child with VATER association have a 1% or less chance of having another baby with the same condition. There have been a few reports of affected individuals with a parent or sibling showing a single feature of the VATER spectrum. There has only been one reported case of a parent and child both affected with multiple VATER features.

Most individuals with VATER association have a normal chromosome pattern. However, a few cases of chromosome differences have been reported in individuals with VATER. One child with VATER had a deletion (missing piece) on the long arm of chromosome 6. Another male infant had a deletion on the long arm of chromosome 13. There have been other children reported with a chromosome 13 deletion and VATER-like features. This infant was the first reported with the deletion to have all of the VACTERL main features. He was also the first with this chromosome deletion to have a connection between his trachea and esophagus. Another child with VATER association had an extra marker chromosome. This is a fragment of chromosomal material present in the cell in addition to the usual 46 chromosomes. This child’s marker was found to contain material from chromosome 12. These cases have not led to the discovery of a gene involved in VATER.

There has only been one VATER case reported in which a genetic change was identified. That female infant died one month after birth because of kidney failure. Her mother and sister later were diagnosed with a mitochondrial disease. Mitochrondria are the structures in the cell that create energy by chemical reactions. The mitochrondria have their own set of DNA and a person inherits mitochondrial DNA from the mother only. Stored kidney tissue from the deceased infant was analyzed and she was found to have the same genetic change in her mitochondrial DNA as her mother and sister. The researchers

could not prove that the gene change caused the infant’s features of VATER.

There are two subtypes of VACTERL that seem to be inherited. Both types have the typical VACTERL features in addition to hydrocephaly (excess water in the brain). They are abbreviated VACTERL-H. The first subtype was described in 1975 by David and O’Callaghan and is called the David-O’Callaghan subtype. It appears to be an autosomal recessive condition. Parents of an affected child are carriers of a normal gene and a gene that causes VACTERL-H. When both parents are carriers there is a 25% chance for an affected child with each pregnancy. The second subtype is called Hunter-MacMurray and appears to be an X-linked recessive condition. In X- linked conditions, the disease-causing gene is located on the X chromosome, one of the sex-determining chromosomes. Females have two X chromosomes and males have an X chromosome and a Y chromosome. A female who carries a disease-causing gene on one of her X chromosomes shows no symptoms. If a male inherits the gene he will show symptoms of the condition. A woman who carries the VACTERL-H X-linked gene has a 25% chance of having an affected son with each pregnancy. Both of these subtypes are rare and account for a small number of VACTERL cases.

Demographics

VATER is rare, but has been reported worldwide. Exact incidence can be difficult to determine because of different criteria for diagnosis. Some studies consider two or more VATER features enough to make the diagnosis. Other studies require at least three features to diagnose VATER. Also, infants with features of VATER may have other genetic syndromes such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18, Holt-Oram syndrome, TAR syndrome, and

Fanconi anemia. VATER does appear to be more frequent in babies of diabetic mothers. It is also more frequent in babies of mothers taking certain medications during pregancy, including estroprogestins, methimazole, and doxorubicin.

Signs and symptoms

VATER has six defining symptoms. “V” represents vertebral abnormalities. Approximately 70% of individuals with VATER have some type of spine difference such as scoliosis (curvature of the spine), hemivertebrae (unusually aligned, extra, or crowded spinal bones), and sacral absence (absence of spinal bones in the pelvic area). Vertebral differences are usually in the lumbrosacral area (the part of the spine in the small of the back and pelvis). “A” represents anal atresia which is present in about 80% of individuals with VATER. This is an

1170 |

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

unusual arrangment or connection of the anus and rectum. Imperforate anus is also common, in which the anal opening does not form or is covered. Babies with this problem cannot pass bowel movements out of the body. “TE” stands for tracheo-esophageal fistula. About 70% of babies with VATER have this problem. This is a connection between the two tubes of the throat—the esophagus (carries food from mouth to stomach) and the trachea (windpipe). This connection is dangerous because it causes breathing problems. These babies can also get food into their windpipe and choke. Lung infections are also common with this connection. Some infants may be missing part of their esophagus, causing problems with choking and feeding. These babies spit up their food because the food cannot get to the stomach.

In the original VATER association, “R” stood for radial differences and renal (kidney) problems. The radius is the forearm bone that connects to the hand on the side of the thumb. Radial differences can include an absent or underdeveloped radius. This often results in a twisted, unusual position of the arm and hand. The thumb can also be small, misplaced, or absent. Kidney problems are present in about half of individuals with VATER. These can include missing kidneys, kidney cysts, or fluid buildup in the kidneys. Some individuals also have an abnormal position of the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body).

The expanded VACTERL includes “C” for cardiac (heart) problems and “L” for limb differences. The heart problems are usually holes or other structural abnormalities. Limb differences usually involve the arms rather than the legs. The term includes more general differences such as extra fingers, shortened or missing fingers, and underdeveloped humerus (the bone of the upper arm). These differences often cause unusual arm or hand positions (bent or twisted) and fingers that are short, absent, or misplaced.

Many people have proposed an expanded VACTERL pattern to include differences of the reproductive system and absent sacrum. Small or ambiguous (not clearly male or female) genitalia, or misplaced reproductive parts are common in VACTERL. They tend to occur more frequently in infants with anal and kidney abnormalities. They are seen less often with esophagus and arm features. Absence of the bones of the sacrum (spine in the pelvis area) is also commonly seen in VACTERL.

Individuals with VATER have an average of seven to eight features or differences at birth. About twothirds of features involve the lower body (intestines, genitals, urinary system, pelvis, and lower spine). Onethird of features involve the upper body (arms, hands, heart, esophagus, and trachea). In addition to the typical VATER features, infants may have problems with

the intestines or excess water in the brain. Intestinal problems (such as missing sections of intestine) are more common in individuals with anal or esophagus features.

Shortly after birth, infants with VATER often have failure to thrive. This involves feeding problems and difficulty gaining weight. Their development is often slow. Infants with visible signs of VATER should immediately be checked for internal signs. Quick detection of problems with the trachea, esophagus, heart, and kidneys can lead to earlier treatment and prevention of major illness. Most individuals with VATER have normal mental development and mental retardation is rare.

Diagnosis

Some features of VATER can be seen on prenatal ultrasound so that the diagnosis may be suspected at birth. Ultrasound can see differences of the vertebrae, heart, limbs, limb positions, kidneys, and some reproductive parts. Other problems that are associated with VATER on ultrasound are poor fetal growth, excessive fluid in the womb, absent or collapsed stomach, and one artery in the umbilical cord instead of the usual two. VATER features that cannot be seen on ultrasound are differences of the anus, esophagus, and trachea.

Even if VATER is suspected before birth, an infant must be examined after birth to determine the extent of features. The entire pattern of internal and external differences will determine if the infant has VATER association, another multiple birth defect syndrome, or a genetic syndrome (such as Holt-Oram syndrome, TAR syndrome, or Fanconi anemia). Since VATER overlaps with some genetic syndromes, some infants may fit the VATER pattern and still have another diagnosis. VATER only describes the pattern of related birth defects. Since the genetic causes of VATER are unknown, genetic testing is not available. A family history focusing on VATER features can help to determine if an infant has a sporadic case or a rare inherited case.

Treatment and management

Treatment for VATER involves surgery for each separate feature. Holes in the heart can be closed by surgery. Structural problems of the heart can also often be repaired. Prognosis is best for infants with small or simple heart problems. Some vertebral problems may also need surgery. If the vertebral differences cause a problem for the individual’s posture, braces or other support devices may be needed.

Problems with the trachea and esophagus can also be repaired with surgery. Before surgery the infant

association VATER

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

1171 |

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

usually needs a feeding tube for eating. This will stop the choking and spitting up. The infant may also need oxygen to help with breathing. If the trachea and esophagus are connected, the connection is separated first. Once separated, the two trachea ends and esophagus ends can be sealed together. When part of the esophagus is missing, the two loose ends are connected. If the gap between the loose ends is too big, surgery may be delayed until the esophagus grows. Some infants still have problems after surgery. They may have a difficult time swallowing or food may get stuck in their throat. They may also have asthma and frequent respiratory infections.

Surgery can also repair problems of the anus and rectum. Before surgery, a temporary opening is made from the small intestine to the abdomen. This allows the infant to have bowel movements and pass stool material. An anal opening is created with surgery. The intestines and rectum are adjusted to fit with the new anal opening. The temporary opening on the abdomen may be closed immediately after surgery or it may be closed weeks or months later. Surgeons must be very careful not to damage the nerves and muscles around the anus. If they are damaged, the individual may lose control of their bowel movements.

Differences of the hands and arms can also be improved with surgery. Infants with underdeveloped or absent radius may have a stiff elbow, stiff wrist, or twisted arm. Surgery can loosen the elbow and wrist to allow for movement. The arm can also be straightened. If needed, muscles from other parts of the body can be put into the arm. This may also improve movement. Even after surgery, individuals may not have completely normal function of the muscles and tendons of the arms and hands.

Prognosis

Prognosis for individuals with VATER association depends on the severity of features. Infants with complex heart problems or severe abnormalities of the anus, trachea, or esophagus have a poorer prognosis. Infants with several features that require surgery have a higher death rate than infants that need minor surgery or no surgery. Survival also depends on how quickly internal problems are discovered. The sooner problems with the heart, anus, trachea, and esophagus are found and repaired, the better the outlook for the infant. One study estimated that infants with VATER have a death rate 25 times higher than healthy infants. Another study estimated that up to 30% of individuals with VATER die in the newborn period.

Resources

PERIODICALS

Beasley, S.W., et al. “The Contribution of the Adriamycininduced Rat Model of the VATER Association to Our Understanding of Congenital Abnormalities and Their Embryogenesis.” Pediatric Surgery International 16 (2000): 465–72.

Botto, Lorenzo D., et al. “The Spectrum of Congenital Anomalies of the VATER Association: An International Study.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 71 (1997): 8–15.

Rittler, Monica, Joaquin E. Paz, and Eduardo E. Castilla. “VATERL: An Epidemiologic Analysis of Risk Factors.”

American Journal of Medical Genetics 73 (1997): 162–69. Rittler, Monica, Joaquin E. Paz, and Eduardo E. Castilla.

“VACTERL Association, Epidemiologic Definition and Delineation.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 63 (1996): 529–36.

ORGANIZATIONS

VACTRLS Association Family Network. 5585 CY Ave. Casper, WY 82604. http://www.homestead.com/VAFN/VAFN

.html .

VATER Connection. 1722 Yucca Lane, Emporia, KS 66801. (316) 342-6954. http://www.vaterconnection.org .

WEBSITES

“Vater Association.” Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim

.cgi?id=192350 .

Amie Stanley, M.S.

Velocardiofacial syndrome see Deletion

22q1 syndrome

Ventriculomegaly see Hydrocephalus

I Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

Definition

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome is an inherited condition characterized by tumors that arise in multiple locations in the body. Some of these tumors cause cancer and some do not. Many of the tumors seen in VHL are vascular, meaning that they have a rich supply of blood vessels.

Description

In the mid-1800s, ophthalmologists described vascular tumors in the retina, the light-sensitive layer that lines the interior of the eye. These tumors, called angiomas,

1172 |

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

KEY TERMS

Adrenal gland—A triangle-shaped endocrine gland, located above each kidney, that synthesizes aldosterone, cortisol, and testosterone from cholesterol. The adrenal glands are responsible for salt and water levels in the body, as well as for protein, fat, and carbohydrate metabolism.

Angioma—A benign tumor composed of blood vessels or lymph vessels.

Benign—A non-cancerous tumor that does not spread and is not life-threatening.

Bilateral—Relating to or affecting both sides of the body or both of a pair of organs.

Broad ligament—The ligament connecting the ovaries to the uterus.

Computed tomography (CT) scan—An imaging procedure that produces a three-dimensional picture of organs or structures inside the body, such as the brain.

Cyst—An abnormal sac or closed cavity filled with liquid or semisolid matter.

Epididymus—Coiled tubules that are the site of sperm storage and maturation for motility and fertility. The epididymis connects the testis to the vas deferens.

Hemangioblastoma—A tumor of the brain or spinal cord arising in the blood vessels of the meninges or brain.

Hormone—A chemical messenger produced by the body that is involved in regulating specific bodily functions such as growth, development, and reproduction.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—A technique that employs magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of internal body structures and organs, including the brain.

Mutation—A permanent change in the genetic material that may alter a trait or characteristic of an individual, or manifest as disease, and can be transmitted to offspring.

Pancreatic islet cell—Cells located in the pancreas that serve to make certain types of hormones.

Pheochromocytoma—A small vascular tumor of the inner region of the adrenal gland. The tumor causes uncontrolled and irregular secretion of certain hormones.

Renal cell carcinoma—A cancerous tumor made from kidney cells.

Retina—The light-sensitive layer of tissue in the back of the eye that receives and transmits visual signals to the brain through the optic nerve.

were not cancerous but were associated with vision loss. In 1904, a German ophthalmologist named Eugen von Hippel noted that these retinal angiomas seemed to run in families. Twenty-three years later, Arvid Lindau, a Swedish pathologist, reported a connection between these retinal angiomas and similar tumors in the brain, called hemangioblastomas. Like angiomas, hemangioblastomas are vascular tumors as well. After Lindau noted this association, there were many more reports describing families in which there was an association of retinal angiomas and central nervous system (CNS) hemangioblastomas. Other findings were found to be common in these families as well. These findings included cysts and/or tumors in the kidney, pancreas, adrenal gland, and various other organs. In 1964, Melmon and Rosen wrote a review of the current knowledge of this condition and named the disorder von Hippel-Lindau disease. More recently, the tumors in the retina were determined to be identical to those in the CNS.

They are now referred to as hemangioblastomas, rather than angiomas.

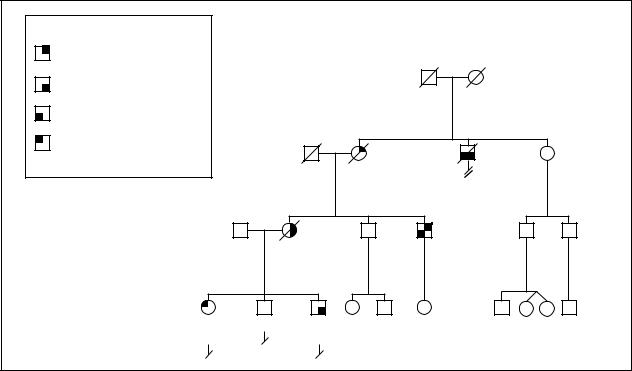

There are four distinct types of VHL, based on the manifestations of the disorder. Type 1 is characterized by all VHL-related tumors except those in the adrenal gland. Type 2 includes tumors of the adrenal gland and is subdivided into type 2A (without kidney tumors or cysts in the pancreas), type 2B (with kidney tumors and cysts in the pancreas), and type 2C (adrenal gland tumors only).

Genetic profile

VHL is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. This means that an affected person has a 50% chance of passing the disease on to each of his or her children. Nearly everyone who carries the mutation in the VHL gene will show signs of the disorder, usually by the age of 65.

syndrome Lindau-Hippel Von

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

1173 |

syndrome |

Key: |

|

|

|

Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome |

||

|

|

|

|

An Example of Type 2B |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Renal cell carcinoma |

|

|

|

|

Autosomal Dominant |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Hippel-Lindau |

Cerebellar hemangioblastoma |

|

|

|

Died young |

d.70y |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Pheochromocytoma |

|

|

|

of unknown |

CHF (congestive heart failure) |

||

|

|

|

cause |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Retinal angioma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Von |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

dx = Diagnosed |

|

d.75y |

dx.42y |

|

70y |

||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

d.44y |

|

d.39y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

+Epididymal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cystadenoma |

|

|

59y |

|

dx.32y |

|

53y |

46y |

|

|

|

|

d.45y |

|

|

dx.28y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

31y |

28y |

26y |

29y |

22y |

15y |

|

|

dx.28y |

|

dx.25y |

|

|

|

|

(Gale Group)

VHL is caused by a change or mutation in the VHL gene. This gene is located on chromosome 3 and produces the VHL protein. The VHL protein is a tumor suppressor, meaning that it controls cell growth. When the VHL gene is changed, the VHL protein does not function correctly and allows cells to grow out of control. This uncontrolled cell growth forms tumors and these tumors may lead to cancer.

People without VHL have two working copies of the VHL gene, one on each chromosome 3. Each of these copies produces the VHL protein. People affected with VHL inherit one working copy and one non-working copy of the gene. Thus, one gene does not make the VHL protein but the corresponding gene on the other chromosome continues to make the functional protein. In this case, cell growth will still be controlled because the VHL protein is available. However, as this person lives, another mutation may occur in the working gene. If this happens, the VHL protein can no longer be made. Cell growth cannot be controlled and tumors develop. Mutations like this occur in various organs at various times, leading to multiple tumors forming in distinct parts of the body over a period of time.

The majority of patients with VHL syndrome inherited the mutation from one of their parents. In approxi-

mately 1–3% of cases, there is no family history of the disorder and VHL occurs because of a new mutation in the affected individual. If a person appears to be an isolated case, it is important that the parents have genetic testing. It is possible that a parent could carry the mutation in the VHL gene but have tumors that do not cause any noticeable symptoms. If a parent is affected, each of his or her future children would have a 50% of being affected with VHL. If both parents test negative for the VHL gene mutation, each future child has a 5% risk of inheriting VHL. This small risk is to account for the rare possibility that one parent carries the mutation in his or her sex cells (egg or sperm) but does not express the disorder in any of the other cells of the body.

Demographics

VHL occurs in approximately one in 36,000 live births. It is seen in all ethnic groups and both sexes are affected equally.

Signs and symptoms

There are several characteristic features of VHL but no single, unique finding. Thus, it is necessary that many different specialties be involved in the diagnosis and

1174 |

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

management of the disease. This approach will ensure proper, thorough care for these patients.

VHL is characterized by hemangioblastomas, tumors that arise in the blood vessel. These tumors are found in the central nervous system, or the brain and spinal cord. They most commonly present between the ages of 25 and 40 years and are the first symptom of VHL in 40% of cases. It is common to see multiple tumors. They may appear at the same time or at different times. These tumors generally grow slowly but, in some cases, may enlarge more rapidly. Hemangioblastomas seen in VHL are benign (non-cancerous) but may produce symptoms depending on their size, site, and number. Hemangioblastomas in the brain may lead to headache, vomiting, slurred speech, or unsteady and uncoordinated movements. These symptoms are usually due to the tumors disrupting brain function or causing increased pressure in the brain. Hemangioblastomas of the spine are usually accompanied by pain and can lead to loss of sensation and motor skills. Some of these tumors may fail to cause any observable symptoms.

In patients with VHL, hemangioblastomas also appear in the retina, the light-sensitive layer that lines the interior of the eye. These tumors occur in approximately half the cases of VHL and may be the first sign that a person is affected. It is common to see numerous retinal hemangioblastomas develop throughout a person’s lifetime. They often can be found in both eyes. These tumors have been detected as early as the age of 4 years but are more typically found between the ages of 21 and 28 years. They often occur without symptoms, but can be detected on a routine eye exam. If untreated or undetected, they may cause the retina to detach from the eye. This condition is accompanied by bleeding and leads to vision loss and possibly blindness.

Approximately 50–70% of individuals with VHL also have numerous cysts on their kidneys. Cysts are sacs or closed cavities filled with liquid. In VHL, these cysts are vascular and frequently occur in both kidneys; however, they rarely result in noticeable symptoms. In some cases, these cysts may develop into renal cell carcinomas. These are cancerous tumors that are composed of kidney cells. Seventy percent of people affected with VHL will develop this type of kidney tumor during their lifetime. This type of cancer is generally diagnosed between the ages of 41 and 45 years. By the time this condition produces symptoms, it is likely that the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body. If this is the case, the tumors will respond poorly to chemotherapy and radiation, two common cancer treatments.

VHL can also cause multiple cysts in the pancreas. These occur at the average age of 41 years and are vas-

cular in nature. Pancreatic cysts rarely cause problems and tend to grow fairly slowly. Pancreatic islet cell tumors can occur as well but are unrelated to the cysts. Islet cells in the pancreas produce hormones. Hormones are substances that are produced in one organ and then carried through the bloodstream to another organ where they perform a variety of functions. When tumors occur in the islet cells of the pancreas, these cells secrete too many hormones. This increase in hormones rarely leads to recognizable symptoms. Pancreatic islet cell tumors grow slowly and are non-cancerous.

Additionally, tumors in the adrenal gland, called pheochromocytomas, are common in VHL. The adrenal glands are located on top of each kidney. They secrete various hormones into the bloodstream. Pheochromocytomas are made of cells from the inner region of the adrenal gland. These tumors are benign but can be numerous and are often located in both adrenal glands. They can be confined to the inside of the adrenal gland or they can travel and appear outside of it. Some do not cause any observable symptoms. Others can lead to high blood pressure, sweating, and headaches.

In approximately 10% of cases, tumors can also be found in the inner ear. Most often, these tumors occur in both ears. They may lead to hearing loss of varying severity. This hearing loss may be one of the first signs that an individual is affected with VHL. Less commonly, a person may complain of dizziness or ringing in the ear due to these inner ear tumors.

Men with VHL commonly have tumors in the epididymus. The epididymus is a structure that lies on top of the testis and serves as the site for sperm storage and maturation for motility and fertility. If these tumors occur bilaterally, they can lead to infertility. However, as a general rule, they do not result in any health problems. The equivalent tumor in females is one that occurs in the broad ligament. This ligament connects the ovaries to the uterus. These tumors, however, are much less common than those in the epididymus.

It is important to note that wide variation exists among all individuals affected with VHL in regards to the age of onset of the symptoms, the organ systems involved, and the severity of disease.

Diagnosis

VHL can be diagnosed clinically, without genetic testing, in some cases. If a person has no family history of the disorder, a diagnosis of VHL can be made if one of the following criteria are met:

•the patient has two or more hemangioblastomas of the retina or CNS

syndrome Lindau-Hippel Von

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

1175 |

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

•the patient has a single hemangioblastoma along with one of the other tumors or cysts that are commonly associated with the disorder

A diagnosis of VHL can also be established in a person who has a positive a family history of the disorder if they show one or more of the following before the age of 60:

•retinal hemangioblastoma

•CNS hemangioblastoma

•pheochromocytoma

•multiple pancreatic cysts

•tumor of the epididymus

•multiple renal cysts

•renal cell carcinoma

Several tests are available that can assist in the diagnosis of VHL. They can also determine the extent of symptoms if the diagnosis has already been made. A computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are often utilized for these purposes. These procedures serve to produce images of various soft tissues in the body, such as the brain and abdominal area. In someone with VHL, they are used to assess for the presence of CNS hemangioblastomas and other tumors associated with the disorder, such as pheochromocytomas and inner ear tumors. Pheochromocytomas may also cause abnormal substances to be released into the urine. A urinalysis can detect these substances and, therefore, suggest the existence of these tumors. Additionally, ultrasound examination can assist in evaluating the epididymus, broad ligament, and kidneys. Ultrasound examination involves the use of high frequency sound waves. These sound waves are directed into the body and the echoes of reflected sound are used to form an electronic image of various internal structures.

VHL can also be diagnosed via examination of the VHL gene on the molecular level. This type of testing detects approximately 100% of people who are affected with the disorder and is indicated for confirmation of the diagnosis in cases of suspected or known VHL. Molecular genetic testing examines the VHL gene and detects any mutations, or changes, in the gene. Most often, in this disorder, the gene change involves a deletion of a part of the gene or a change in one of the bases that makes up the genetic code.

Since molecular testing is so accurate, it is recommended even in cases where the clinical criteria for diagnosis are not met. It is possible that the tumors associated with VHL are present but are not causing any observable symptoms. Thus, even if a person does not meet the diagnostic criteria mentioned above, molecular testing can be used as a means of “ruling out” VHL with a high degree

of certainty. For patients with numerous, bilateral pheochromocytomas or for those who have a family history of these tumors, molecular testing is strongly suggested since these tumors may be the only signs of the disorder in those with VHL type 2C.

VHL can be diagnosed at various ages, ranging from infancy to the seventh decade of life or later. The age of diagnosis depends on the expression of the condition within the family and whether or not asymptomatic lesions are detected.

Treatment and management

There is no treatment for VHL because the genetic defect cannot be fixed. Management focuses on routine surveillance of at-risk and affected individuals for early detection and treatment of tumors.

For at-risk relatives of individuals diagnosed with VHL, molecular genetic testing is recommended as part of the standard management. If a person tests negative for the mutation, costly screening procedures can be avoided. If an at-risk relative has not been tested for the mutation, surveillance is essential for the early detection of signs of VHL.

The following groups of people should be routinely monitored by a physician familiar with VHL:

•individuals diagnosed with VHL

•individuals who are asymptomatic but who have tested positive for a mutation in the VHL gene

•individuals who are at-risk due to a family history of the disorder but have not undergone molecular testing

For these groups of people, annual physical examinations are recommended, along with neurologic evaluation for signs of brain or spinal cord tumors. Additionally, an eye exam should be completed annually, beginning around the age of five years. These exams can detect retinal hemangioblastomas, which often produce no clinical symptoms until serious damage occurs. When a person reaches the age of 16, an abdominal ultrasound should be completed annually as well. Any suspicious findings should be followed up with a CT scan or MRI. If pheochromocytomas are in the family history, blood pressure should be monitored annually. A urinalysis should be completed annually as well, beginning at the age of five. Although the majority of tumors associated with VHL are benign in nature, they all have a small possibility of becoming cancerous. For this reason, surveillance and early detection is very important to the health of those affected with VHL.

If any tumors are identified by the above surveillance, close monitoring is necessary and surgical intervention may be recommended. Hemangioblastomas of the brain

1176 |

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

or spine may be removed before they cause symptoms. They may also be followed with yearly imaging studies and removed only after they begin to cause problems. Most of these tumors require surgical removal at some point and results are generally good. Retinal hemangioblastomas can be treated with various techniques that serve to decrease the size and number of these tumors.

Early surgery is recommended for renal cell carcinoma. Extreme cases may require removal of one or both kidneys, followed by a transplant. Additionally, pheochromocytomas should be surgically removed if they are causing symptoms. Inner ear tumors, however, generally are slow-growing. The benefit of removing one of these tumors must be carefully compared to the risk of deafness, which may result from the surgery. Epididymal and broad ligament tumors generally do not require surgery.

Prognosis

The average life expectancy of an individual with VHL is 49 years. Renal cell carcinoma is the leading cause of death for affected individuals. If an affected person is diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma, their average life expectancy decreases to 44.5 years. CNS hemangioblastomas are responsible for a significant proportion of deaths in affected individuals as well, due to the effects of the tumor on the brain.

Resources

BOOKS

The VHL Handbook: What You Need to Know About VHL.

Brookline, MA: VHL Family Alliance, 1999.

PERIODICALS

Couch, Vicki, et al. “Von Hippel-Lindau Disease.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 75 (March 2000): 265–272.

Friedrich, Christopher A. “Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome: A Pleiomorphic Condition.” Cancer 86, no. 11 Suppl (December 1, 1999): 2478–2482.

ORGANIZATIONS

VHL Family Alliance. 171 Clinton Ave., Brookline, MA 02455-5815. (800) 767-4VHL. http://www.vhl.org .

WEBSITES

Schimke, R. Neil, Debra Collins, and Catharine A. Stolle. “Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome.” GeneClinics. http://www

.geneclinics.org/profiles/vhl/index.html .

“Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome.” Genes and Disease.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/disease/VHL.html .

Mary E. Freivogel, MS

von Recklinghausen disease see

Neurofibromatosis

I von Willebrand disease

Definition

Von Willebrand disease is caused by a deficiency or an abnormality in a protein called von Willebrand factor and is characterized by prolonged bleeding.

Description

The Finnish physician Erik von Willebrand was the first to describe von Willebrand disease (VWD). In 1926 Dr. von Willebrand noticed that many male and female members of a large family from the Aland Islands had increased bruising (bleeding into the skin) and prolonged episodes of bleeding. The severity of the bleeding varied between family members and ranged from mild to severe and typically involved the mouth, nose, genital and urinary tracts, and occasionally the intestinal tract. Excessive bleeding during the menstrual period was also experienced by some of the women in this family. What differentiated this bleeding disorder from classical hemophilia was that it appeared not to be associated with muscle and joint bleeding and affected women and men rather than just men. Dr. von Willebrand named this disorder hereditary pseudohemophilia.

Pseudohemophilia, or von Willebrand disease (VWD) as it is now called, is caused when the body does not produce enough of a protein called von Willebrand factor (vWF) or produces abnormal vWF. vWF is involved in the process of blood clotting (coagulation). Blood clotting is necessary to heal an injury to a blood vessel. When a blood vessel is injured, vWF enables blood cells called platelets to bind to the injured area and form a temporary plug to seal the hole and stop the bleeding. vWF is secreted by platelets and by the cells that line the inner wall of the blood vessels (endothelial cells). The platelets release other chemicals, called factors, in response to a blood vessel injury, which are involved in forming a strong permanent clot. vWF binds to and stabilizes factor VIII, one of the factors involved in forming the permanent clot.

A deficiency or abnormality in vWF can interfere with the formation of the temporary platelet plug and also affect the normal survival of factor VIII, which can indirectly interfere with the production of the permanent clot. Individuals with VWD, therefore, have difficulty in forming blood clots and as a result they may bleed for longer periods of time. In most cases the bleeding is due to an obvious injury, although it can sometimes occur spontaneously.

VWD is classified into three basic types: type 1, 2, and 3 based on the amount and type of vWF that is pro-

disease Willebrand von

GALE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GENETIC DISORDERS |

1177 |