Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorder / Gale Encyclopedia of Genetic Disorders, Two Volume Set - Volume 1 - A-L - I

.pdf

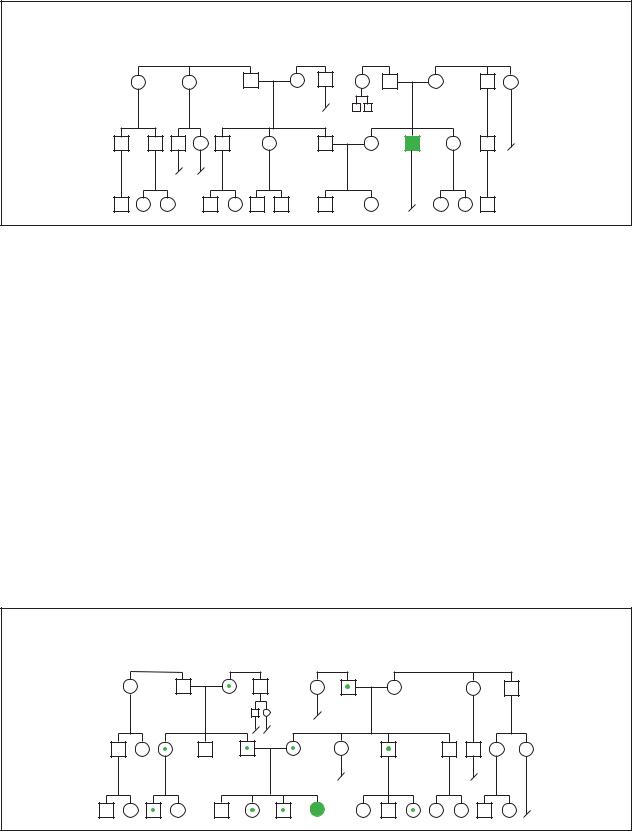

Congenital Hypothyroidism

Sporadic

syndrome hypothyroid Congenital

(Gale Group)

Diagnosis

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are critical to avoid the profound consequences of hypothyroidism. The signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are often subtle in newborns, only to manifest themselves later in life when permanent damage has been done. Before the implementation of screening for hypothyroidism in the 1970s, most children with the disease suffered growth and mental retardation, as well as neurological and psychological deficits.

Most cases of congenital hypothyroid syndrome are now detected by a screening test performed during a newborn’s first few days of life. Every state offers testing, and most states require it. The test for hypothyroidism is part of a battery of standard screening tests designed to diagnose important conditions. A sample of the child’s blood is analyzed for levels of thyroxine (T4), thyroid-stimulat-

ing hormone (TSH), or both, depending on the individual state or country. Some states also require a second round of screening performed one to four weeks later.

Once the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism is made, other tests can pinpoint the nature of the abnormality. X rays of the hip, shoulder, or skull often reveal characteristically abnormal patterns of bone development. Scintigraphy is a method by which images of the thyroid gland and any ectopic thyroid tissue are obtained to determine if the thyroid is absent or ectopic. But treatment should not be delayed for these other tests. Early treatment offers a good probability of normal development.

Treatment and management

Treatment of congenital hypothyroidism requires replacement of deficient thyroid hormones with levothyroxine, an oral tablet form of T4. There is no need to

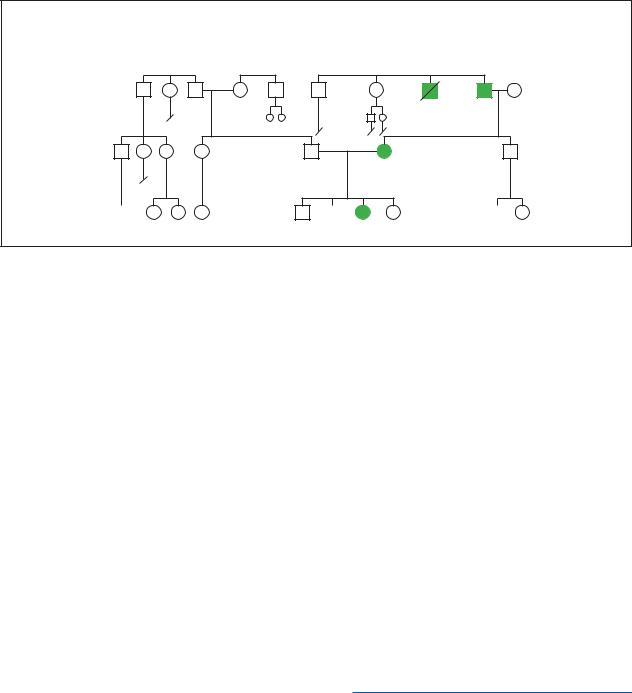

Congenital Hypothyroidism

AR abnormalities in thyroid hormone syndrome, TS synthesis, or TS response

(Gale Group)

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

271 |

Conjoined twins

Congenital Hypothyroidism,

AD defective response to thyroid hormone post 1970 1st gen.

60y |

58y |

53y |

54y |

48y |

50y |

49y |

45y |

43y |

|

d.childhood |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

15y |

12y |

28y |

25y |

|

|

|

40y |

36y |

30y |

29y |

|

27y |

25y |

|

23y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20y |

10y |

9y |

4y |

6y |

|

4y |

2y |

1y |

4y |

2y |

|

(Gale Group)

directly replace T3, since T4 is converted to T3 by the liver and kidney. Hypothyroid children usually require more levothyroxine per pound of body weight than hypothyroid adults do. The importance of prompt and adequate treatment cannot be overemphasized. Delays in treatment result in permanent stunting of physical, mental, and sexual development.

Blood levels of T4 should be checked regularly to ensure appropriate replacement. The blood levels of TSH should also be monitored since TSH is an indicator of the effectiveness of T4 replacement. As the child develops, the physical growth rate also provides a good measure of treatment.

Prognosis

If congenital hypothyroidism is detected and treated early in life, the prognosis is quite good. Most children will develop normally. However, the most severely affected infants may have mild mental retardation, speech difficulty, hearing deficit, short attention span, or coordination problems.

ORGANIZATIONS

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Guidelines from Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

Kevin O. Hwang, MD

Congenital ichthyosis-mental retardationspasticity syndrome see Sjögren Larsson syndrome

Congenital isolated hemihypertrophy see

Hemihypertrophy

Congenital megacolon see Hirschsprung disease

Congenital retinal blindness see Leber amaurosis congenita

Resources

BOOKS

“Hypothyroidism.” In Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, edited by Richard E. Behrman, et al. 16th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 2000.

“The Thyroid.” In Cecil Textbook of Medicine, edited by Lee Goldman, et al. 21st ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 2000.

“Thyroid Hormone Deficiency.” In Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, edited by Jean D. Wilson, et al. 19th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1998.

I Conjoined twins

Definition

Conjoined twins are an extremely rare type of identical twins who are physically joined at birth.

Description

Scientists believe conjoined twins form because of a delay in the fertilized egg’s division. In normal identical

272 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

twins, the egg splits at four to eight days after fertilization. In conjoined twins, however, the split occurs sometime after day 13. Instead of forming two separate embryos, the twins remain partially attached as they develop inside the womb. In most cases, conjoined twins do not survive more than a few days past birth because of a high rate of malformed organs and other severe birth abnormalities. However, surgical separations have been successful in conjoined twins that have a superficial physical connection.

Conjoined twins are commonly referred to as Siamese twins, although this is now considered a derogatory term. The phrase Siamese twins originated from the famous conjoined twins Eng and Chang Bunker, who were born in Siam (Thailand) in 1811.

Some conjoined twins are attached at the upper body, others may be joined at the waist and share a pair of legs. Conjoined twins often share major organs such as a heart, liver, or brain. Medical experts have identified several types of conjoined twins. They are classified according to the place their bodies are joined. Most of the terms contain the word pagus, which means “fastened” in Greek.

Upper body

Cephalopagus: A rare form that involves conjoined twins with fused upper bodies and two faces on opposite sides of a single head.

Craniopagus: Conjoined twins with separate bodies and one shared head is a rare type and only occurs in 2% of cases.

Thoracopagus: About 35% of conjoined twin births have this common form of the condition, which joins the upper bodies. These twins usually share a heart, making surgical separation nearly impossible.

Lower body

Ischopagus: About 6% of conjoined twins are attached at the lower half of the body.

Omphalopagus: The type of conjoined twins that are attached at the abdomen and that often share a liver accounts for approximately 30% of all cases.

Parapagus: About 5% of conjoined twins are joined along the side of their lower bodies.

Pygopagus: About 19% of conjoined twins are joined back to back with fused buttocks.

Rare types

Dicephalus: Twins that share one body, but have two separate heads and necks.

K E Y T E R M S

Breech delivery—Birth of an infant feet or buttocks first.

Craniopagus—Conjoined twins with separate bodies and one shared head.

Dicephalus—Conjoined twins who share one body but have two separate heads and necks.

Fetus in fetu—In this case, one fetus grows inside the body of the other twin.

Ischopagus—Conjoined twins who are attached at the lower half of the body.

Omphalopagus—Conjoined twins who are attached at the abdomen.

Parapagus—Conjoined twins who are joined at the side of their lower bodies.

Parasitic twins—Occurs when one smaller, malformed twin is dependent on the larger, stronger twin for survival.

Pygopagus—Conjoined twins who are joined back to back with fused buttocks.

Thoracopagus—Conjoined twins joined at the upper body who share a heart.

Zygote—The cell formed by the uniting of egg and sperm.

Parasitic twins: This occurs when one smaller, malformed twin is dependent on the larger, stronger twin for survival.

Fetus in fetu: In this unusual case, one fetus grows inside the body of the other twin.

Genetic profile

Scientists are still searching for the cause of conjoined twins. They believe a combination of genetic and environmental factors may be responsible for this rare condition.

Demographics

Conjoined twins occur in one out of every 50,000 births. Many such pregnancies are terminated before birth, or the infants are stillborn. Conjoined twins are always identical and of the same sex. They are more often female than male, by a ratio of 3:1. Conjoined twins are more likely to occur in Africa, India, or China than in the United States. Conjoined twins have appeared in triplet

twins Conjoined

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

273 |

Conjoined twins

These conjoined twins developed until the 17 week of pregnancy. It is difficult for conjoined twins to survive when they share the same key organs such as these siblings. (Custom Medical Stock Photo, Inc.)

and quadruplet births, but no cases of conjoined triplets or quadruplets have ever been reported. Most parents of conjoined twins are younger than 35 years old.

Signs and symptoms

Approximately 50% of women who are pregnant with conjoined twins will develop excess fluid surrounding the fetuses, which can lead to premature labor and an increased risk of miscarriage. Conjoined twins joined at the abdomen (omphalopagus) are more likely to be breech babies. In breech births, infants are born feet or buttocks first instead of head first. Most omphalopagus conjoined twins are born by cesarean section to increase their odds of survival.

Conjoined twins can be born with a complication called hydrops, which causes excessive fluid to build up in an infant’s body and can be life-threatening. Those who survive past birth may experience congenital heart

disease, liver or kidney disease, physical or mental disabilities, and intestinal blockages.

Diagnosis

Physicians typically try to determine if a woman is having conjoined twins at an early stage so that the parents can have an option to terminate the pregnancy if the odds of survival are low. Ultrasound imaging is a technique in which high-frequency sound waves create a picture of a developing fetus inside the womb and is often used to make the diagnosis. Initial diagnosis is possible at 10-12 weeks of gestation, but it is difficult to determine which body structures are involved until 20 weeks of gestation.

In utero, the three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test is another important diagnostic tool that helps more precisely define which body parts of the conjoined twins are connected. An abdominal x ray of the mother is used to look for connected bones in conjoined twin embryos.

Treatment and management

Early diagnosis is key so that families and healthcare providers can begin to plan for the birth of conjoined twins. Because of the high rate of miscarriage and difficult labor, most conjoined twins are delivered by cesarean section. Some conjoined twins have survived and lived full lives without serious medical interventions. If the twins do not share a large number of organs, however, physicians typically will recommend a surgical separation.

A large medical team must be assembled for a surgical separation. Physicians prefer to wait for a few months after birth, but that may not be possible if the twins are born with life-threatening congenital abnormalities. The type of surgery that is performed is determined by where the twins are connected. Doctors will often insert tissue expansion devices into the twins’ skin before the operation to promote better healing at the site of separation.

Conjoined twins who survive a surgical separation will have many ongoing health-care needs, from wound care to prosthetic limbs and special diets. As the twins grow up and start school, they also may need counseling to help them adjust.

Prognosis

The majority of conjoined twin pregnancies are not successful. However, most conjoined twins who undergo a planned surgical separation several months after birth do survive. The survival rate for conjoined twins who need an emergency separation at birth is approximately 44%.

274 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

Resources

BOOKS

Martel, Joanne. Millie-Christine: Fearfully and Wonderfully Made. John F. Blair, 2000.

Segal, Nancy L. Entwined Lives: Twins and What They Tell Us about Human Behavior. Dutton, 1999.

Strauss, Darin. Chang and Eng. EP Dutton, 2000.

PERIODICALS

Johnson, Kimberly. “I Had Siamese Twins.” Ladies’ Home Journal. 110, Issue 3 (March 1993): 24-27.

Paden, Cheryl Sacra, and Sondra Forsyth. “Miracle Babies.” Ladies’ Home Journal 116, Issue 11 (November 1999): 145-151.

ORGANIZATIONS

Center for Loss in Multiple Birth, Inc. (CLIMB). PO Box 1064, Palmer, AK 99654. (907) 222-5321.

Center for Study of Multiple Birth. 334 E. Superior St., Suite 464, Chicago, IL 60611. (312) 266-9093. http://www

.multiplebirth.com .

Conjoined Twins International. PO Box 10895, Prescott, AZ 86304-0895.

National Organization of Mothers of Twins Clubs. PO Box 438, Thompson Station, TN 37179. (615) 595-0936.http://www.nomotc.org .

Twins Foundation. PO Box 6043, Providence, RI 02940-6043. (401) 751-8946. Twins@twinsfoundation.com.

WEBSITES

Conjoined Twins fact sheet from Children’s Hospital of Columbus. www.childrenscolumbus.org/gen/twinsfact

.html .

“Conjoined Twins.” (April 30, 2001). TwinStuff.com.http://www.twinstuff.com/conjoined.htm .

OTHER

Twin Falls Idaho. Videotape. Sony Pictures Classics, 1990.

Melissa Knopper

Cooley’s anemia see Beta-thalassemia

I Corneal dystrophy

Definition

Corneal dystrophy is a condition that causes a layer of the cornea to cloud over and impair visual clarity. It is usually a bilateral problem, which means it occurs in both eyes equally. There are more than 20 different forms of inherited corneal dystrophies. A corneal dystrophy can occur in otherwise healthy individuals. Depending on the type of condition and the age of the individual, a corneal dystrophy may either cause no problems, moderate

vision impairment, or severe difficulties that require surgery.

Description

The cornea is the outside layer of the eye, and comprises five layers itself, including the outer epithelium, the Bowman’s layer, the stroma, or middle, layer that takes up about 90% of the entire cornea, the Descemet’s membrane, and the endothelium. In most cases, the central (stromal) layer of the cornea is involved.

Some corneal dystrophies are named after the individual who discovered them, while others are descriptive of the pattern seen with the dystrophy or the location of the disease. The key forms of corneal dystrophy are congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED), epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, granular dystrophy, lattice dystrophy, macular corneal dystrophy, Meesmann’s corneal dystrophy, posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPD), and ReisBucklers’ dystrophy.

Genetic profile

Genetic alterations (mutations) causing corneal dystrophies have been mapped to 10 different chromosomes. Some dystrophies have not yet been mapped, including Fuchs’ dystrophy.

Some corneal dystrophies have the same genetic address. Mutations on the BIGH3 gene of chromosome 5q31 cause granular corneal dystrophy and ReisBucklers’ dystrophy. Macular corneal dystrophy has been mapped to an altered gene on chromosome 16. The mutation causing congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy has been mapped to 20p11-20q11. Lattice type I is linked to the 5q31 locus (location), while lattice type II dystrophy is linked to the 9q34 locus. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy has been linked to the 20q11 locus.

Most corneal dystrophies, with the exception of congenital endothelial corneal dystrophy and macular dystrophy, are autosomal dominant. In dominant disorders, a single copy of the mutated gene (received from either parent) dominates the normal gene and results in the appearance of the disease. The risk of transmitting the disorder from parent to offspring is 50% for each pregnancy.

Both congenital endothelial corneal dystrophy and macular dystrophy are autosomal recessive. This means the affected person inherits the same abnormal gene for the same trait from both parents; each parent is a carrier for the disease, but they usually will have no symptoms of the disease. The risk of transmitting the disease to each pregnancy is 25%.

dystrophy Corneal

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

275 |

Corneal dystrophy

K E Y T E R M S

Basement membrane—Part of the epithelium, or outer layer of the cornea.

Bowman’s layer—Transparent sheet of tissue directly below the basement membrane.

Corneal transplant—Removal of impaired and diseased cornea and replacement with corneal tissue from a recently deceased person.

Descemet’s membrane—Sheet of tissue that lies under the stroma and protects against infection and injuries.

Edema—Extreme amount of watery fluid that causes swelling of the affected tissue.

Endothelium—Extremely thin innermost layer of the cornea.

Epithelium—The layer of cells that cover the open surfaces of the body such as the skin and mucous membranes.

Hyaline—A clear substance that occurs in cell deterioration.

Stroma—Middle layer of the cornea, representing about 90% of the entire cornea.

Demographics

The diversity of corneal dystrophies diseases makes it difficult to provide specific demographic data. Some dystrophies appear in early childhood or even infancy, such as Reis-Bucklers’ dystrophy. Others may not appear until middle age or beyond, as with Fuchs’ dystrophy. Women are at greater risk for Fuchs’ dystrophy, especially those over age 40. However, most corneal dystrophies present before age 20.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms vary with the type of corneal dystrophy and the location of the site. Most experts categorize these diseases based on whether they are located on the anterior (outer) layer, stromal (middle) layer, or endothelial (inner) layer.

Anterior corneal dystrophies

The epithelium, or the “basement membrane,” and the Bowman’s layer together comprise the anterior, or outer part, of the cornea. Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, also known as Cogan’s map-dot-fingerprint dystrophy, is a disorder that causes errors in refractions of the eye and may also present with microscopic cysts.

This disease results from excessive fluid (edema) and swelling of the basement membrane into the epithelium. Symptoms of this disease are map-like dots, opaque circles, or thin lines that are formed in a swirled pattern like fingerprints. Individuals with this disorder feel like they have something irritating in the eye and experience pain and light sensitivity (photophobia).

The tiny opaque collagen fibers that cause ReisBucklers’ dystrophy create a linear or ring-like pattern. People with this disease have recurrent painful erosions of the cornea and may also suffer from severe visual impairment. Reis-Bucklers’ is usually noticed in an infant or young child who suddenly has very red eyes. To the ophthalmologist, the cornea looks like frosted glass. This disorder may recur several times per year and disappear when affected individuals are in their 20s or 30s.

Stromal dystrophies

The primary dystrophies found in the stromal layer are granular dystrophy, lattice dystrophy, and macular dystrophy. Granular dystrophy is so named because of the small opaque areas caused by deposits of hyaline, a substance that accumulates as cells deteriorate. Lattice dystrophy is caused by deposits of amyloid, the same substance that accumulates in the brain in people with Alzheimer disease. Both granular dystrophy and lattice dystrophy have been identified in family members in Avellino, Italy, and these dystrophies are sometimes grouped together and called Avellino corneal dystrophy. Lattice and granular dystrophies can cause severe eye pain. With lattice dystrophy, by about age 40, an affected person’s vision can be very obscured and a corneal transplant is required.

Endothelial dystrophies

Fuchs’ dystrophy is the most common of the endothelial dystrophies and is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. It is characterized by blurred vision, hypersensitivity to light (photophobia), and two to eight acute inflammatory attacks per year. It may also cause ulceration and erosion of the cornea. Fuchs’ can cause deterioration of endothelial cells and result in corneal guttata, which are thickenings or leakages from the Descemet’s membrane of the cornea. These guttata eventually cause edema (excessive fluid) to leak into the stromal or epithelial areas.

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPD), an autosomal dominant disease, also causes edema, although it affects a larger area than Fuchs’ dystrophy. It usually does not cause vision impairment.

Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) comprises two types. The autosomal dominant

276 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

dystrophy Corneal

Gradual deterioration of the corneal tissue layers results in corneal dystrophy. As the tissue deteriorates, a gritty appearance such as that shown above, becomes apparent. (Custom Medical Stock Photo, Inc.)

form is CHED 1 and the recessive form is CHED 2. CHED 1 can occur in early childhood and may also cause hearing loss. The key symptoms of CHED 1 are sensitivity to light and excessive tearing. CHED 2 is present at birth and is more severe than CHED 1. In both CHED 1 and 2, the cornea presents with a milky haze or the appearance of ground glass.

Macular dystrophy is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. It can present as early as age three and up to about age nine and is very debilitating. This disorder is caused by deposits of keratin sulfate (sulfur-containing fibrous proteins) and becomes increasingly painful. The child will have a feeling of something in the eye and also experience photophobia (sensitivity to light).

Diagnosis

Corneal dystrophy may be identified by an optometrist and diagnosed by an ophthalmologist. The findings determine the existence and type of corneal dystrophy. The presence, size, and shape of any opaque material in the eyes are considered.

The affected cornea of a person with lattice dystrophy will have a ground glass appearance, while granular

deposits indicate granular dystrophy. The examination can also reveal the presence of amyloid deposits, which are typical of individuals with lattice dystrophy.

Treatment and management

Treatment depends on the severity of the disease. If the affected person is in acute pain, treatment with eye drops, antibiotics, and other solutions is necessary. Some doctors advise affected people with eye edema to use a hair dryer at arm’s length to dry some of the edema. Soft contact lenses may also help. Individuals with increasingly severe vision problems may need a corneal transplant.

For other forms of corneal dystrophy, affected people may need artificial tears and other medications. Some individuals may need laser treatment, such as phototherapeutic keratectomy (PK), which is the removal of part of the corneal stroma, or they may need a corneal transplant.

Prognosis

With most forms of corneal dystrophy, the disease progresses as the affected person ages. The severity of the conditions varies and a particular form of the disease may

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

277 |

Cornelia de Lange syndrome

cause few or no problems or may also cause severe visual difficulties requiring surgery. Cases must be evaluated individually.

Resources

PERIODICALS

Akimune, Chika, et al. “Corneal Guttata Associated with the Corneal Dystrophy Resulting from a Big-h3 R124H Mutation.” British Journal of Ophthalmology 84 (January 2000).

Bass, Sherry J. “Unraveling the Genetic Mysteries of the Corneal Dystrophies.” Review of Optometry 138 (January 15, 2001).

Kabat, Alan G., and Joseph W. Sowka. “How to Detect and Deal with Dystrophies and Degenerations.” Review of Optometry 136 (November 1999).

Korvatska, E., et al. “Mutation Hot Spots in 5q31-Linked Corneal Dystrophies.” American Journal of Human Genetics 62 (1998).

National Eye Institute. “Fact Sheet: The Cornea and Corneal Disease.” April 2000.

ORGANIZATIONS

Eye Bank Association of America. 1015 18th St. NW, Suite 1010, Washington, DC 20036. (202) 775-4999.http://www.restoresight.org/ .

National Association for Visually Handicapped. 22 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. (212) 889-3141.http://www.navh.org .

National Eye Institute. 31 Center Dr., Bldg. 31, Rm 6A32, MSC 2510, Bethesda, MD 20892-2510. (301) 496-5248. 2020@nei.nih.gov. http://www.nei.nih.gov .

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). PO Box 8923, New Fairfield, CT 06812-8923. (203) 746-6518 or (800) 999-6673. Fax: (203) 746-6481. http://www

.rarediseases.org .

WEBSITES

“Corneal Dystrophies.” National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health http://www.nei.nih.gov/publications/ asptest/c.htm .

“Report of the Corneal Diseases Panel: Program Overview and Goals.” National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.

http://www.nei.nih.gov/publications/plan/NEIPlan/ corneal.htm .

Christine Adamec

I Cornelia de Lange syndrome

Definition

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is a congenital syndrome of unknown origin diagnosed on the basis of facial characteristics consisting of synophrys (eyebrows joined

at the midline), long eyelashes, long philtrum (area between the upper nose and the lip), thin upper lip, and a downturned mouth. It is a multisystemic disease that most often affects the gastrointestinal tract and the heart. Patients also present with mental retardation as well as many skeletal system malformations. It is estimated that this syndrome affects one in 10,000 newborns.

Description

This syndrome was named after the physician who described the condition in Amsterdam in 1933. It is also known as Amsterdam Dwarf Syndrome of de Lange. In 1916, another physician named Brachmann first described a more severe form of this syndrome and therefore it is also known as Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. As of 2001, it is known that there are three distinct categories of this condition.

The most severe form of this condition is the Type I or “classic form”. Patients with this form have a prenatal growth deficiency that is noticeable after birth. In addition, these patients are marked with a distinct face and moderate to profound mental retardation. These individuals often have major deformities in the gastrointestinal tract and heart which may lead to severe incapacity or death.

The mild form of this condition is known as the Type II form. This is characterized by similar facial features to that of Type I, however, they may not become apparent until later in life. Along with a less severe preand postnatal growth deficiency, major malformations are seen at a decreased rate or may be absent completely.

Type III Cornelia de Lange syndrome, also called phenocopy, includes patients who have phenotypic manifestations of the syndrome that are related to chromosomal aneuplodies or teratogenic factors.

Genetic profile

The syndrome is suspected to be genetic in origin but the mode of transmission is unknown. Most cases are sporadic and are thought to result from a new mutation (an abnormal sequence of the components that make a gene). There is also evidence that this may be transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, thus if only one parent is affected there exists a 50% chance of transmitting the abnormal gene to each child. A gene of chromosome 3 may be responsible for the syndrome.

Demographics

Cornelia de Lange syndrome appears to affect males and females in equal numbers. It is more common to see

278 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

affected females transmitting the trait, however, these women seem to transmit only the mild form to their offspring. It has also been noted that consanguineous relations, or relations within families, may result in an affected child. The recurrence risk has been estimated to be between two and six percent.

Signs and symptoms

Musculoskeletal abnormalities

•Microcephaly. Microcephaly is the term used to describe individuals with an abnormally small head. People with microcephaly have an accompanying small brain, resulting in mild to profound mental retardation.

•Micrognathia. This term is used when characterizing people with an abnormally small mandible or lower jaw bone.

•Nasal. Individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome often have a small nose. Anteversion, or turning, of the nostrils is also seen. A long philtrum (area between the nose and the upper lip) is also characteristic of a patient with Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

•Limb and digit malformations. Limb abnormalities sometimes include relatively short limbs. Limitations of elbow extension is often seen in mild forms. In addition, relative smallness of the hands and/or feet is almost always universal. Oligodactyly (presence of less than five digits on hand or feet), and clinodactyly or bending of the fifth finger and thumbs are also sometimes seen. Webbing of the toes (syndactyly) is also common in patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

•Characteristic facial features. Facial features are possibly the most diagnostic of the physical signs. Patients look similar to each other with the bushy eyebrows joined at the midline, which is known as synophrys. Patients also have long eyelashes, a thin upper lip, and a downturned mouth. In mild cases, this classical appearance may not be present at birth and may take two or three years before becoming obvious. These individuals also have hypertrichosis, which is excessive facial (as well as body) hair.

•Other symptoms. Most patients are also of low birth weight, have a cleft palate, and a low-pitched growl or cry.

Gastrointestinal abnormalities

A number of gastrointestinal (GI) problems can manifest and are by far the most common system involved. Both the upper and lower GI tract can be involved.

•Gastroesophageal reflux. This is caused when acid from the stomach refluxes back into the esophagus. This can

lead to severe heartburn and, if left untreated, can cause damage to the esophagus (reflux esophagitis) due to repeated irritations. Gastroesophageal reflux can also cause symptoms of pulmonary congestion and irritation due to chemical pneumonitis (inflammation of the lung).

•Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is a change from the normal tissue type of the lower esophagus to a different type. This is normally a complication on gastroesophageal reflux and is significant because it may develop into an adenocarcinoma (carcinoma of glandular tissue).

•Esophageal stenosis. A narrowing of the esophagus which may decrease esophageal motility and make feeding difficult.

•Gastric ulcers. The majority of ulcers of the stomach are caused by bacteria. Ulcers of this nature may lead to abdominal discomfort.

•Pyloric stenosis. A narrowing of the pyloric canal that leads from the stomach to the duodenum. This may result in vomiting and diarrhea complicated by electrolyte imbalances.

•Intestinal malrotation. This is a failure during fetal development of normal rotation of the small intestine. This can cause a volvulus, a twisting of the intestine back on itself, cutting-off blood supply to the tissue or possibly an intestinal obstruction.

•Meckel diverticulum. In this condition, there are tiny pouches that protrude in the small intestine. Sometimes ulceration develops and bleeding occurs.

Cardiac abnormalities

Heart problems are not uncommon in patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

•Ventricular septal defect. In this condition the septum of the ventricles (wall between the lower chambers of the heart) is not fully closed. This results in a murmur and can possibly lead to congestive heart failure. Other complications may include infective endocarditis, which is an infection of the endothelium, the tissue that lines the heart.

•Atrial septal defect. This is a defect of the septum between the upper chambers of the heart. It is caused by the persistence of the foramen ovale which is a hole normally present in the fetus that closes at birth. Individuals with this condition may also have a heart murmur.

•Symptoms are normally not present in patients with atrial septal defects but they are at an increased risk of infective endocarditis.

syndrome Lange de Cornelia

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |

279 |

Cornelia de Lange syndrome

•Patent ductus arteriosus. This is a failure of the ductus arteriosus, a blood vessel between the pulmonary artery and the aorta found only in the fetus, to close. Normally, there are symptoms but severe cases may require surgery to close.

•Pulmonary valve stenosis. In this condition, the valve that allows blood to go from the right ventricle to the lungs becomes narrowed. This may result in right-sided heart enlargement and heart failure.

•Tetralogy of Fallot. This is a condition consisting of pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, enlarged right ventricle, and a displaced aorta. This condition results in a decrease in oxygenated blood that is pumped to the body. It can normally be corrected by surgery.

Growth and developmental deficiency

Most people afflicted with Cornelia de Lange syndrome have both prenatal and postnatal growth deficiencies as well as a developmental delay. This may be due to endocrine system involvement concerning a growth hormone delivery problem. Most patients have a characteristically short stature, but often have a pubertal growth spurt at a comparable age to normal individuals.

Developmental delays are numerous and are found in most patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Some of the delays include walking alone, speaking, toilet training, and dressing. In some instances these patients never reach these milestones. Other developmental delays include IQ, which is within the mild to moderate range for mental retardation and averages 53.

Disorders of ears and eyes

Many patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome often have some form of hearing loss. Cases may range from mild to severe, and may affect either one or both ears. This loss can be attributed to a lack of prenatal development of some of the important bony structures associated with the inner ear. In addition, development failure of important neural elements play a role in this hearing loss.

A significant number of Cornelia de Lange syndrome patients have eye and/or vision problems including:

•Myopia. Nearsightedness or shortsightedness is often seen in children diagnosed with Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

•Nystagmus. This is the term used to describe the rhythmical oscillations of the eyes slowly to one side followed by a rapid reflex movement in the opposite

direction. It is usually horizontal, although rotatory or vertical nystagmus may also occur.

•Ptosis. Ptosis is the medical term used to characterize patients having a drooping eyelid(s). This may result from lesions either in the brainstem or in the nerves supplying the muscles that raise the eyelid.

•Nasolacrimal duct fistula. The lacrimal gland secretes tears to keep the eyeball moist and protected. In a nasolacrimal duct fistula the tears are not drained from the eyeball and therefore the patient may develop chronic tearing and discharge from the eyes.

Other symptoms

Other malformations include undescended testicles, which can cause fertility problems. Diaphragmatic hernia is another complication that may lead to GI difficulties. Patients may also have a cleft palate and a low-pitched growl or cry.

Diagnosis

Cornelia de Lange syndrome has no set criteria that can indicate with absolute certainty whether or not a child is afflicted. This is due in part to a lack of specific biochemical markers postnatally that would lead a clinician to a definitive diagnosis. However, diagnosis is made subjectively from the characteristic symptoms that are present in this condition including the ones listed above. Perhaps the most diagnostic tool is the distinguishing face that a patient has, combined with facial hypertrichosis.

Prenatal diagnosis is possible through the use of ultrasound. The association of intrauterine growth retardation, oligodactyly, an absent ulna, underdevelopment of hands, diaphragmatic hernia, and cardiac defects lead to the differential diagnosis. When uncertain, the presence of long eyelashes or unusually long hair on the back restrict the diagnosis to Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

Researchers have also found that maternal serum samples collected from women who gave birth to a child with Cornelia de Lange syndrome revealed low levels of a pregnancy associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) during the second trimester. In addition, it has been noted that an amniotic molecule (5-OH-indole-3-acetic acid), and a fetal serum protein (galactose-1-phosphate-uridyl- trasferase) were increased in afflicted individuals.

Treatment and management

The treatment and management of patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome is strictly symptomatic.

280 |

G A L E E N C Y C L O P E D I A O F G E N E T I C D I S O R D E R S |