- •Contents

- •Предисловие

- •Методическая записка

- •Britain in ancient times. England in the Middle Ages.

- •1. The Earliest Settlers

- •Celtic borrowings in English

- •Latin borrowings in English

- •3. The Anglo-Saxon period

- •The origin of day names

- •4. The Danish Invasion of Britain

- •5. Edward the Confessor

- •1. Beginning of the Norman invasion

- •2. The Norman Conquest

- •3. England in the Middle Ages

- •Church and State

- •Magna Carta and the beginning of Parliament

- •4. Language of the Norman Period

- •5. The development of culture

- •First universities

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. Society

- •Peasants’ Revolt

- •3 Economic development of England

- •Agriculture and industry

- •4. Growth of towns

- •5. The Hundred Years War

- •6. Wars of the Roses

- •7. Pre-renaissance in England

- •Geoffrey Chaucer

- •William Caxton

- •Music, theatre and art

- •Assignments (1)

- •1. Review the material of Section 1 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 1

- •2. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •The English Renaissance

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. The Great Discoveries

- •3. Absolute monarchy

- •4. Reformation

- •5. Counter-Reformation

- •6. Renaissancehumanists

- •Elizabethan Age

- •1. The first playhouses

- •2. Actors and Society

- •3. London theatres

- •4. William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

- •5. Shakespeare and the language

- •1. The reign of James I

- •2. Strengthening of Parliament

- •3. Charles I and Parliament

- •4. The Civil War

- •5. Restoration of monarchy

- •6. Trade in the 17th century

- •7. Political parties

- •S 8. Science, Art and Music cience

- •J 9. Literature ournalism

- •Assignments (2)

- •I. Review the material of Section 2 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 2

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •3. Topics for presentations:

- •Britain in the New Age. Modern Britain.

- •1. The Glorious Revolution

- •2. Political and economic development of the country

- •3. Life in town

- •4. London and Londoners

- •5. The Industrial Revolution

- •6. The Colonial Wars

- •7. The Development of arts

- •8. The Enlightenment

- •1. Napoleonic Wars

- •2. The political and economic development of the country

- •3. Romanticism

- •4. Art and artists

- •5. Victorian Age

- •Victorian Literature

- •1. The beginning of the century

- •2. Britain in World War I

- •3. Social issues in the 1920s

- •4. The General Strike and Depression

- •5. The Abdication

- •6. Britain in World War II

- •7. Britain in the post-war period

- •8. The fall of the colonial system

- •9. The Falklands War

- •10. Britain in international relations

- •11. Britain’s economic development at the end of the century

- •12. Social issues

- •13. 20Th-century literature

- •14. The development of the English language Changes in the language

- •In recent decades the English language in the uk has undergone certain phonetic, lexical and grammatical changes:

- •The spread of English. Variants of English.

- •Spelling differences

- •Phonetic differences

- •Lexical differences

- •Grammatical differences

- •Assignments (3)

- •I. Review the material of Section 3 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 3

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •Cross-cultural notes Chapter 1

- •1. Iberians [aI'bi:rjRnz] – иберы/иберийцы (древние племена, жившие на территории Британских островов и Испании; в III–II вв. До н.Э. Завоеваны римлянами и романизированы.

- •Chapter 2

- •Chapter 3

- •Chapter 4

- •16. William Byrd [bR:d], Thomas Weelkes ['wi:lkIs], John Bull [bul] – Уильям Бэрд, Томас Уилкис, Джон Булл – английские композиторы конца XVI и начала XVII в. Chapter 5

- •8. Dark Lady – Смуглая Леди, незнакомка, часто упоминаемая в сонетах у. Шекспира. Chapter 6

- •Chapter 7

- •Chapter 9

- •Key to Tests

- •Электронный ресурс:

- •119454, Москва, пр. Вернадского, 76

- •119218, Москва, ул. Новочеремушкинская, 26

3. Life in town

England was still a country of small villages. The big cities of the future were only beginning to emerge. After London, the second largest city was Bristol. Its rapid growth and importance was based on the triangular trade: British-made goods were shipped to West Africa, West African slaves were transported to the New World, and American sugar, cotton and tobacco were brought to Britain.

By the middle of the century Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield and Leeds were already big cities. But administratively and politically, they were still treated as villages and had no representation in Parliament.

All towns, old and new, had no drainage system; dirt was seldom or never removed from the streets. Towns often suffered from epidemics. In London, only one child in four grew up to become an adult. The majority of the poorer population suffered from drinking as the most popular drink was gin. Quakers started developing the beer industry and promoting the spread of beer as a less damaging drink. Soon beer drinking became a national habit.

A

4. London and Londoners

The City, or the Square Mile of Money, became the most important district of London. The Lord Mayor was never seen in public except in his rich robe, a hood of black velvet and a golden chain. He was always escorted by heralds and guards. On great occasions, he appeared on horseback or in his gilded coach. A commonly used phrase said, “He who is tired of London is tired of life”. But the 18th century London was, naturally, different from what it became later. The streets were so narrow that wheeled carriages had difficulty in passing each other. Houses were built of brick or stone, as well as of wood and plaster. The upper part of the houses was built much further out than the lower part, so far out that people living on the upper floors could touch each other’s hands by stretching out over the street. Houses were not numbered as the majority of the population were illiterate. Shops, inns, taverns, theatres and coffee-houses had painted signs illustrating their names. The most typical names and pictures were “The Red Lion”, “The Swan”, “The Golden Lamb”, “The Blue Bear”, “The Rose”.

Londoners preferred to walk in the middle of the streets so as to avoid the rubbish thrown out of the windows and open doors. In rainy weather the gutters that ran along the streets, turned into black torrents, which roared down to the Thames, carrying to it all the rubbish from the City. The streets were not lighted at night. Thieves and pickpockets plied their trade without fear of being punished. It was difficult to get about even during the day, let alone at night.

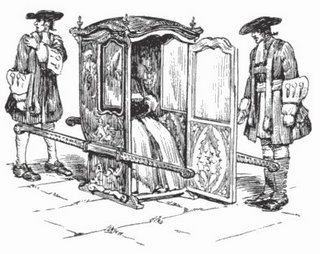

Wealthier

Londoners preferred using the river. The boatmen dressed in blue

garments waited for customers at the head of the steps leading down

to the waterside. Another way of getting about London  was

in a sedan-chair. It was put on two long horizontal poles which were

carried by two men. When ladies went out to pay visits, the lid of

the sedan-chair had to be opened to make room for the fashionable

hair-dresses and hats.

was

in a sedan-chair. It was put on two long horizontal poles which were

carried by two men. When ladies went out to pay visits, the lid of

the sedan-chair had to be opened to make room for the fashionable

hair-dresses and hats.

The introduction of coffee, tea and chocolate as common drinks led to the establishment of coffee-houses. These were a kind of first clubs. Coffee-houses kept copies of newspapers, they became centres of political discussion. Every coffee-house had its own favourite speaker to whom the visitors listened with great admiration. Each rank and profession, each shade of religious or political opinion had its own coffee-house. There were earls and clergymen, university students and translators, printers and index-makers. Men of literature and the wits met at a coffee-house which was frequently visited by the poet John Dryden. Here one could also meet Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Johnson and other celebrities.