- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

19.7 Management |

433 |

|

|

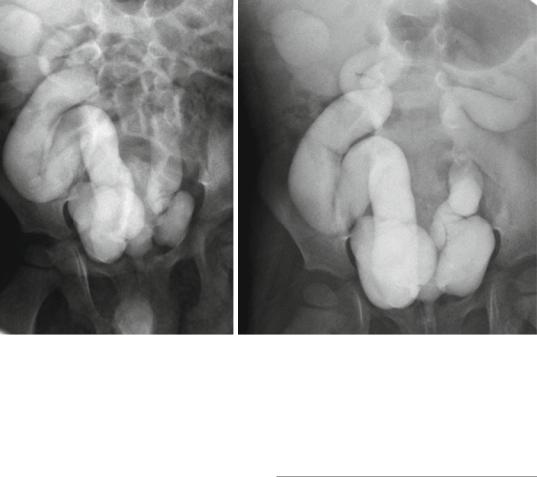

Figs. 19.11 and 19.12 Micturating cystourethrograms showing severe bilateral reflux

–Tc-dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), glucoheptonate, and mercaptoacetyltriglycine (MAG-3) renal scintigraphy provide information about relative renal function.

–The presence of photopenic areas within the kidney indicate scarring or dysplasia.

–An absent or dysplastic kidney is seen as a photopenic area in the renal fossa

–The MAG-3 renal scan with furosemide (Lasix) provides information about renal drainage and possible obstruction.

•Urodynamic studies:

–These provide information about bladder storage and emptying.

–The term “valve bladder” is used to describe patients with PUV and a fibrotic noncompliant bladder. These patients are at risk of developing:

•Hydroureteronephrosis

•Progressive renal deterioration

•Recurrent infections

•Urinary incontinence

–Patients with PUV require periodic urodynamic testing throughout childhood because bladder compliance may further deteriorate over time.

•Cystourethroscopy may be required to formally confirm the diagnosis of posterior urethral valves at the time of intervention (Fig. 19.12).

19.7Management

•The management of patients with posterior urethral valve requires a multidisciplinary team including:

–Pediatric urologists

–Pediatric pulmonologists

–A general pediatrician

–Pediatric nephrologist

–Neonatologists

–Radiologists

–The family

•The aims should be:

–To treat pulmonary distress if present

–To relief urethral obstruction by passing a small size 5 F feeding tube

–Fluid and electrolytes management

–Valve disruption

–Treatment of bladder dysfunction and renal insufficiency

434 |

19 Posterior Urethral Valve |

|

|

•Treatment of the lower urinary tract may influence progression of upper tract disease.

•Few patients with PUV present with bilateral renal dysplasia at birth. Currently, these patients can be treated successfully with peri-

toneal dialysis and subsequently at around 1 year of age with renal transplantation.

•Approximately one third of patients with PUV progress to ESRD and these patients are treated with dialysis and subsequently renal transplantation.

•Growth in these children may be significantly retarded and below the reference range for the child’s age.

•These patients should have a balanced caloric and protein intake to avoid an accelerated rise in serum creatinine levels.

•Renal dysfunction and progression of ESRD can be accelerated by:

–Increased metabolic workload on the kidneys as seen at puberty

–Recurrent infections

–Elevated bladder pressures

–Increased caloric and protein intake

•Prenatal Intervention:

–There remains no clinical consensus about the efficacy and use of prenatal intervention.

–It was shown that there is a link between urine outflow impairment and renal dysplasia.

–Lung hypoplasia is seen in patients with PUVs in association with oligohydramnios.

–Currently, it is difficult to identify fetuses with PUVs who may benefit from prenatal intervention.

–At the present time, there is no single marker or combination of fetal urine markers that is reliable in identifying fetuses with PUVs who may benefit from prenatal intervention.

–Gestational age at diagnosis (<24 weeks) and oligohydramnios have been found to be significant predictors of a worse renal outcome.

–The aim of prenatal intervention in those with PUVs is to decompress the fetal renal tract.

–This limit the associated lung underdevelopment, or pulmonary hypoplasia, that is seen at birth in these patients.

–Fetal surgery is a high risk procedure reserved for cases with severe oligohydramnios.

–This will allow:

•Improved survival

•Preservation of renal function

•Reduction in the respiratory compromise and limb abnormalities seen in association with severe oligohydramnios.

–The specific procedures for in utero intervention include:

•Infusions of amniotic fluid

•Serial bladder aspiration (Serial vesicocentesis)

•A vesicoamniotic shunt.

–The risks of fetal surgery are significant and include limb entrapment, abdominal injury, and fetal or maternal death.

•Treatment of posterior urethral valve is by endoscopic valve ablation.

•There are three specific endoscopic treatments of posterior urethral valves:

–Vesicostomy followed by valve ablation.

–Pyelostomy followed by valve ablation.

–Primary (transurethral) valve ablation.

•Currently, the standard treatment of posterior urethral valve is primary (transurethral) ablation of the valves.

•Urinary diversion is rarely used and only used in selected cases.

•Postoperatively, patients with posterior urethral valve should have regular and long term follow-up.

•Neonatal Management:

–A size 6 Fr urethral catheter or feeding tube should be passed to drain the bladder and antibiotic prophylaxis should be started (e.g. trimethoprim 2 mg/kg).

–In those neonates where it is not possible to pass a catheter, a supra-pubic catheter should be inserted.

–These patients should be followed up closely including urine output and electrolyte measurements.

–These patients may develop polyuria and/ or abnormalities of sodium, potassium and bicarbonate as a result of excessive renal losses secondary to post-obstructive diuresis.

19.7 Management |

435 |

|

|

–Creatinine level should be monitored daily till they normalize.

–In boys born with a history of oligohydramnios and significant pulmonary hypoplasia the priority of management is respiratory support and bladder drainage. Either a urethral or supra-pubic catheter is sufficient to optimize urinary drainage whilst awaiting respiratory stability.

–Neonates and infants who were not suspected to have PUV prenatally may present with:

•Urosepsis

•Obstructive voiding symptoms

•A distended bladder

•Palpable kidneys

•Primary Valve Resection:

–The procedure of choice for PUV is primary valve ablation.

–This should be performed once the baby is stable.

–The patient should be covered with antibiotics.

–A diagnostic cystoscopy using 0° 6/8 Fr neonatal cystoscope is performed.

–The diagnosis of PUV is confirmed.

–The configuration of the bladder neck and appearances of the bladder and ureteric orifices should also be noted.

–A resectoscope is used to resect the valve with either the cold/sickle blade or bugbee electrode.

–Valve resection is typically performed at the 5, 7 and 12 o’clock positions.

–A urethral catheter is placed at the end of the procedure and removed 24–48 h later.

–Complications of primary valve ablation include:

•Bleeding

•Incomplete valve resection

•Urethral stricture

•Inadvertent damage to the external sphincter

–For preterm or very small neonates, endoscopic resection is delayed due to the difficulties of the small caliber of the urethra and potential complications of using the relatively larger instruments.

–These children may be managed with a transurethral or supra-pubic catheter until such time as they are big enough for the procedure.

–As a guide, a body weight of 2.5 kg should allow safe and accurate PUV resection with standard endoscopic instruments.

–An alternative technique for small neonates and to avoid the complications associated with urethral or suprapubic catheters, a vesicostomy is constructed to ensure adequate and continuous bladder drainage.

–It is recommended that all boys have a fol- low-up cystoscopy within 3 months of the primary procedure to ensure completeness of valve ablation.

–Others advocate a repeat MCUG within 3 months of the primary procedure and proceed to cystoscopy only if the MCUG suggests persisting urethral obstruction.

•Cystoscopy:

–Cystoscopy is important to confirm the diagnosis of PUV

–Therapeutic cystoscopy (i.e., transurethral incision of the PUVs):

•Multiple techniques have been described for ablating the valves.

•Currently, PUVs are disrupted under direct vision by cystoscopy using an endoscopic loop, Bugbee electrocauterization, or laser fulguration.

•In extremely small infants (<2,000 g), a 2 F Fogarty catheter may be passed either under fluoroscopic or direct vision for valve disruption.

•It is important to perform valve disruption in the least traumatic way to avoid secondary urethral stricture or injury to the urethral sphincter mechanism.

•A temporary vesicostomy may be performed in small infants with small urethra that does not admit available cystoscopic instruments.

•Bladder management:

–Place a 5 F or 6 F urethral catheter to allow for bladder drainage.

–Cystoscopic valve fulguration can be performed within the first few days of life.

436 |

19 Posterior Urethral Valve |

|

|

–A vesicostomy can be performed as a temporary solution in those with a small urethra that can not accommodate the instrument.

–Cutaneous ureterostomies are rarely performed and reserved for those with secondary ureterovesical junction obstruction from bladder hypertrophy.

–Severe or prolonged urethral obstruction can lead to a fibrotic, poorly compliant bladder. This is secondary to increased bladder collagen deposition and detrusor muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia. This will led to:

•Poor compliance of the urinary bladder

•Elevated urinary bladder storage pressures

•Increased risk of vesicoureteric reflux

•Increased risk for hydroureteronephrosis

•Increased risk of urinary incontinence

–The use of urodynamic testing to assess bladder compliance help identify patients at risk.

–Some of these patients may respond to anticholinergic medication, such as oxybutynin.

–The use of clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) may help some of these patients to achieve continence by preventing the bladder from overfilling.

–In patients who do not gain adequate bladder capacity and safe compliance despite optimal medical management, augmentation cystoplasty may be required.

•Surgical treatment:

–The surgical treatment of patients with PUVs varies according to age, bladder status, and renal status.

–Prenatal surgery has been reported in patients diagnosed with PUV with the goal of improving postnatal outcomes.

–Antenatal intervention with vesicoamniotic shunting would improve postnatal renal function.

–However, identification of those patients who may benefit from this early intervention remains unclear and because of this prenatal intervention remains limited.

–Postnatal primary valve ablation:

•Transurethral incision of the PUV during the first few days of life is the preferred treatment.

•The valves can be incised at the 12-, 5-, and 7-o’clock positions, with either a cold knife or electrocautery.

•Some surgeons prefer to leave a catheter in place for 2–3 days after the procedure.

•Approximately two thirds of patients have successful valve ablation with one procedure.

•One third of patients require a second incision.

•Because approximately one third of patients will require a second valve incision, some authors recommend routine surveillance cystoscopy 1–2 months after initial incision to evaluate and treat any residual valve.

•The timing of the postoperative VCUG varies and ranges from several days to several months.

–Vesicostomy:

•This is reserved for patients with small urethral size that cannot accommodated the available instruments.

•This allows free bladder drainage.

•It is important to create an adequate stoma as a large vesicostomy may be complicated by bladder prolapse while a small stoma may result in stomal stenosis and inadequate bladder emptying.

–Cutaneous ureterostomies:

•Bilateral cutaneous ureterostomies can be performed to provide for urinary drainage.

•Techniques for cutaneous ureterostomy include:

–End stomal ureterostomy

–Loop ureterostomy

–Y-ureterostomy (in which the ureter is divided and one end is brought to the skin and the other is reanastomosed in a uretero-ureterostomy)

–Ring ureterostomy