- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

334 |

12 Urinary Tract Infection in Infants and Children |

|

|

•Children with grade IV or V VUR or a significantly abnormal renal and urinary bladder ultrasound should be evaluated further for a possible surgical management.

•Constipation should be addressed in infants and children who have had a UTI to help prevent subsequent infections.

•There is some evidence that cranberry juice decreases symptomatic UTIs over 12-months, particularly in women with recurrent UTIs.

•The effectiveness of cranberry juice in children is less certain, and the high dropout rate in studies indicates that cranberry juice may not be acceptable for long-term prevention.

Antibiotics used for prophylaxis

Antibiotic |

Single daily dose |

Sulfamethoxazole and |

5–10 mg/kg SMZ, |

trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP) |

1–2 mg/kg TMP |

|

PO |

Trimethoprim |

1–2 mg/kg PO |

Nitrofurantoin |

1–2 mg/kg PO |

|

|

Cephalexin |

10 mg/kg PO |

Further Reading

1. [Guideline] Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–6.

3.American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):595–610.

4.Bloomfield P, Hodson EM, Craig JC. Antibiotics for acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD003772.

5. Finnell SM, Carroll AE, Downs SM. Technical report—diagnosis and management of an initial UTI in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e749–70.

6. Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia Nieto V, Valenciano B, Campos A, Young L. Clinical significance of primary

vesicoureteral reflux and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3): 626–32.

7. Girardet P, Frutiger P, Lang R. Urinary tract infections in pediatric practice. A comparative study of three diagnostic tools: dip-slides, bacterioscopy and leucocyturia. Paediatrician. 1980;9(5–6):322–37.

8. Glissmeyer EW, Korgenski EK, Wilkes J, et al. Dipstick screening for urinary tract infection in febrile infants. Pediats. 2014;133(5):e1121–7.

9. Goldsmith BM, Campos JM. Comparison of urine dipstick, microscopy, and culture for the detection of bacteriuria in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1990;29(4):214–8.

10. Heldrich FJ, Barone MA, Spiegler E. UTI: diagnosis and evaluation in symptomatic pediatric patients. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(8):461–72.

11. Hoberman A, Charron M, Hickey RW, Baskin M, Kearney DH, Wald ER. Imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):195–202.

12. Hoberman A, Wald ER, Hickey RW, et al. Oral versus initial intravenous therapy for urinary tract infections in young febrile children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(1 pt 1):79–86.

13. Hom J. Are oral antibiotics equivalent to intravenous antibiotics for the initial management of pyeloneophritis in children? Pediatr Child Health. 2010;15(3): 150–2.

14. Jepson RG, Williams G, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD001321.

15.Keren R, Chan E. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials comparing shortand long-course

antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infections in children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5), E70.

16. Lunn A, Holden S, Boswell T, Watson AR. Automated microscopy, dipsticks and the diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(3):193–7.

17.Michael M, Hodson EM, Craig JC, Martin S, Moyer VA. Short versus standard duration oral antibiotic therapy for acute urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2003;(1):CD003966.

18. Montini G, Toffolo A, Zucchetta P, et al. Antibiotic treatment for pyelonephritis in children: multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7616):386.

19.Mori R, Lakhanpaul M, Verrier-Jones K. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in children:

summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2007;335(7616): 395–7.

20. Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, Bordugo A, Cattaneo A, Ronfani L, et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6): e1489–94.

Further Reading |

335 |

|

|

21. Salo J, Ikäheimo R, Tapiainen T, Uhari M. Childhood urinary tract infections as a cause of chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):840–7.

22. Schoen EJ, Colby CJ, Ray GT. Newborn circumcision decreases incidence and costs of urinary tract infections during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):789–93.

23. Schroeder AR, Chang PW, Shen MW, Biondi EA, Greenhow TL. Diagnostic accuracy of the urinalysis for urinary tract infection in infants <3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):965–71.

24. Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(4): 302–8.

25.Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):853–8.

26.Supavekin S, Surapaitoolkorn W, Pravisithikul N, Kutanavanishapong S, Chiewvit S. The role of DMSA renal scintigraphy in the first episode of urinary tract infection in childhood. Ann Nucl Med. 2013;27(2): 170–6.

27.Toffolo A, Ammenti A, Montini G. Long-term clinical consequences of urinary tract infections during childhood: a review. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(10): 1018–31.

28. Tosif S, Baker A, Oakley E, Donath S, Babl FE. Contamination rates of different urine collection methods for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections in young children: an observational cohort study. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(8):659–64.

29. Tran D, Muchant DG, Aronoff SC. Short-course versus conventional length antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in children: a meta-analysis of 1279 patients. J Pediatr. 2001;139(1):93–9.

30.Wald ER. Vesicoureteral reflux: the role of antibiotic prophylaxis. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):919–22.

31. Wan J, Skoog SJ, Hulbert WC, Casale AJ, Greenfield SP, Cheng EY, et al. Section on Urology response to new Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of UTI. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e1051–3.

32. Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, Cooper J, Kleijnen J. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):4.

33. Williams G, Craig JC. Long-term antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(3):CD001534.

34. Zorc JJ, Kiddoo DA, Shaw KN. Diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(2):417–22.

Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias |

13 |

Complex |

13.1Introduction

•Bladder exstrophy (also known as Ectopia vesicae) is a congenital anomaly that exists as part of the exstrophy-epispadias complex.

•It is characterized by protrusion of the open urinary bladder through a defect in the lower abdominal wall.

•Bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex is a spectrum of rare congenital malformations involving the urinary, genital, and musculoskeletal systems in which the bladder remains open through a lower abdominal defect.

•Bladder exstrophy-epispadias-cloacal exstrophy complex is the most severe and comprises a spectrum of anomalies involving the urinary

tract, genital tract, musculoskeletal system and sometimes the intestinal tract.

•The bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex comprises a spectrum of congenital abnormalities that includes (Figs. 13.1 and 13.2):

–Classic bladder exstrophy

–Epispadias

–Cloacal exstrophy

–Other rare variants

–The spectrum often include abnormalities of the bony pelvis, pelvic floor, and genitalia

•The underlying embryologic mechanism leading to this spectrum of anomalies is unknown but it is believed that all represent a spectrum of the same embryological defect. It is thought to result from failed reinforcement of the cloacal membrane by underlying mesoderm.

|

SMALL OMPHALOCELE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

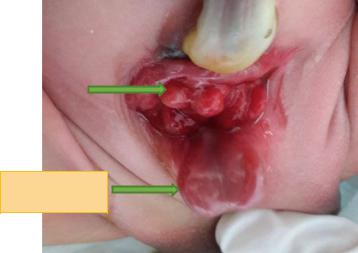

Fig. 13.1 A clinical |

|

|

|

|

|

½ URINARY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

½ URINARY |

||

photograph showing |

|

|

|

||

BLADDER |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

BLADDER |

||

classic cloacal |

|

|

|

|

|

exstrophy. Note the |

|

|

|

|

|

open urinary bladder |

|

|

|

|

|

into two halves and the |

|

|

|

|

|

ileocecal region |

|

|

|

|

|

protruding in the |

|

|

|

|

|

middle of the bladder. |

|

|

|

|

|

Note the small |

|

|

|

ILEOCECAL REGION |

|

omphalocele |

|

|

|

|

|

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017 |

337 |

||||

A.H. Al-Salem, An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_13

338 |

|

|

13 Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 13.2 |

A clinical |

|

|

photograph showing |

|

|

|

classic bladder |

|

|

|

exstrophy. Note the |

|

|

|

open urinary bladder. |

|

|

|

Note also the associated |

OPEN URINARY |

|

|

complete epispadias |

|

||

BLADDER |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COMPLETE

EPISPADIAS

•The incidence:

–The birth prevalence of classic bladder exstrophy has been estimated to be between

1in 10,000 and 1 in 50,000 livebirths. Others reported a prevalence of 3.3 per 100,000 births.

–Males are affected two to three times more often than females.

–Isolated epispadias occurs in approximately 1 in 112,000 live male births and

1in 400,000 live female births.

–The prevalence of Cloacal exstrophy is 1 in 200,000–400,000 births.

•The risk of bladder exstrophy in children born to parents with bladder extrophy is approximately 500-fold greater than the general population.

•The classic manifestation of bladder exstrophy is characterized by:

–A defect in the abdominal wall occupied by both the exstrophied bladder as well as a portion of the urethra

–A flattened puborectal sling

–Separation of the pubic symphysis

–Shortening of the pubic ramii

–External rotation of the pelvis

–Females also have:

• A displaced and narrowed vaginal orifice

• A bifid clitoris

• Divergent labia

•Patients diagnosed intra-uterine with bladder extrophy should be referred to specialized centers for further evaluation and management.

•Modern therapy is aimed at surgical reconstruction of the bladder and genitalia.

–Staged Repair of bladder Exstrophy:

•The initial step is closure of the abdominal wall, often requiring a pelvic osteotomy.

•This leaves the patient with penile epispadias and urinary incontinence.

•At approximately 6 months of age the patient then undergoes repair of the epispadias after testosterone stimulation.

•Finally, bladder neck repair usually is done around the age of 4–5 years, though this is dependent upon a bladder with adequate capacity and, most importantly, an indication that the child is interested in becoming continent.

–Complete Primary Repair of bladder Exstrophy:

•The bladder closure is combined with an epispadias repair.

•Epispadias is a congenital malformation of males in which the urethra opens on the upper surface (dorsum) of the penis.

•Epispadias is an uncommon congenital malformation of the penis and rarely occur as an isolated defect.

13.1 Introduction |

339 |

|

|

Figs. 13.3 and 13.4 Clinical photographs showing epispadias. In the first picture, the epispadias is limited to the glans while in the second one there is complete epispadias

•It is seen more commonly as part of the epispadias-exstrophy complex.

•It is now possible to diagnose exstrophyepispadias complex antenatally using ultrasound and recently fetal magnetic resonance imaging. This is important to council the parents and also to transfer these patients in-utero to specialized centers with a team experienced in their management. The antenatal ultrasonography findings suggestive of exstrophyepispadias complex include the following:

–Failure to visualize the bladder

–Lower abdominal wall mass

–Low-set umbilical cord

–Abnormal genitalia

–Increased pelvic diameter

–Omphalocele

–Limb abnormalities

–Myelomeningocele

–Elephant Trunk sign from prolapsed intestine

•Early attempts at bladder exstrophy repair were unsuccessful and for many years the management for exstrophy consisted of excision of the exstrophic bladder and urinary diversion commonly by ureterosigmoidostomy.

•Anatomical defects in classic bladder exstrophy:

–The urinary bladder is open on the lower abdomen

–The urinary bladder mucosa is fully exposed through a triangular fascial defect on the lower abdomen.

–The abdominal wall appears long because of a low-set umbilicus on the upper edge of the urinary bladder plate.

–The distance between the umbilicus and anus is foreshortened.

–The rectus muscles diverge distally, attaching to the widely separated pubic bones.

–Inguinal hernias are frequently associated with bladder extrophy.

•>80 % of males, and >10 % of females with bladder extrophy have inguinal hernias.

•This is due to wide inguinal rings and the lack of an oblique inguinal canal.

–The phallus (Figs. 13.3, 13.4, and 13.5):

•It is short and broad.

•It is characterized by an upward curvature (dorsal chordee).

•The glans lies open and flat like a spade.

•The dorsal component of the foreskin is absent.

•The urethral plate is open and extends the length of the phallus.

•The bladder plate and urethral plate are in continuity, with the verumontanum

340 |

13 Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex |

|

|

and ejaculatory ducts visible within the prostatic urethral plate.

–The anus is anteriorly displaced with a normal sphincter mechanism.

•Anatomical defects in epispadias:

–The urethra opens on the upper surface (dorsum) of the penis. The extent of this is variable from only the glanular part to the whole urethra.

Fig. 13.5 A clinical photograph showing epispadias as part of classic extrophy. Note the site of closure of bladder extrophy

½ URINARY BLADDER

Fig. 13.6 A clinical photograph showing cloacal extrophy. Note the urinary bladder divided into two halves. Note the ileocecal junction in the middle between the two halves of the bladder. Note also the associated large omphalocele

–The pubic symphysis is generally widened but only mildly.

–The rectus muscles are divergent distally

–This can be an isolated anomaly or more commonly part of the extrophy-epispadias complex.

•Anatomical defects in cloacal exstrophy (Fig. 13.6):

–The bladder is open and separated into two halves

–The exposed interior of the cecum is within it.

–Openings to the remainder of the hindgut and to one or two appendices are evident within the cecal plate.

–The terminal ileum may prolapse as a “trunk” of bowel onto the cecal plate.

–The phallus:

•The penis is generally quite small and bifid

•A hemiglans is located just caudal to each hemibladder.

•Infrequently, the phallus may be intact in the midline.

•In females, the clitoris is bifid and two vaginas are present.

–The anus is absent.

–Nearly all patients have an associated omphalocele.

OMPHALOCELE

½ URINARY BLADDER

ILEOCECAL

AREA