- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology |

223 |

|

|

capacity of the ureter by peristalsis or as the result of ureteral atony that accompany a gram-negative urinary tract infection.

•Primary refluxing obstructed megureter:

–This occurs in the presence of an incompetent VUJ that allows reflux through an adynamic distal segment.

7.3Etiology

and Pathophysiology

•Primary obstructive megaureter:

–It is a common cause of obstructive uropathy in children.

–There is a general agreement that there is no true narrowing at the VUJ.

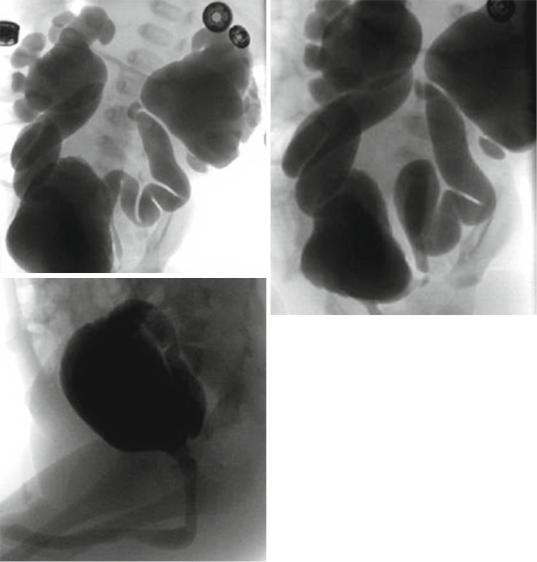

Figs. 7.12, 7.13, and 7.14 Micturating cystourethrogram showing severe bilateral reflux and megaureters. Note the absence of posterior urethral valve

224 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Congenital Megaureter |

||

|

|

||||||||

– This is a functional obstruction secondary |

– This was supported by the finding of TGF- |

||||||||

to a distal adynamic juxtavesical segment |

β in the aperistalitic segment but not in the |

||||||||

0.5–4 cm long that is unable to transport |

dilated ureter and since TGF-β is not nor- |

||||||||

urine at acceptable rates. |

|

|

mally found in the ureter, a developmental |

||||||

– This leads to proximal ureteric dilatation. |

abnormality may explain its pathogenesis. |

||||||||

– The exact etiology of this aperistatic seg- |

– This also may explain the frequent sponta- |

||||||||

ment is not known. |

|

|

neous resolution of primary megaureter |

||||||

– Several etiological theories have been pro- |

within the first 2 years of postnatal life, |

||||||||

posed including: |

|

|

where the circular muscular pattern, which |

||||||

• |

Excessive collagen deposition. |

is typical of the fetal ureter, changes pro- |

|||||||

• Increased matrix deposition alters cell- |

gressively into the double muscle layers of |

||||||||

|

to-cell junctions and disrupts myoelec- |

the full-term infant. |

|

|

|||||

|

trical propagation and peristalsis. |

– The degree of ureteric dilatation that results |

|||||||

• |

Segmental changes of ureter muscle |

depends on the amount of urine forced to |

|||||||

|

cells, where there is atrophy of the inner |

accumulate proximally. |

|

|

|||||

|

longitudinal layer that conducts the per- |

– This in turn is determined by the degree of |

|||||||

|

istaltic waves and hypertrophy of the |

distal obstruction and urinary output. |

|||||||

|

outer circular layer that causes |

– The dilated ureter provide a larger reservoir |

|||||||

|

obstruction. |

|

|

|

and hence less likely to transmit damaging |

||||

• |

Thick circumferential periureteral tis- |

pressure to the kidney. |

|

|

|||||

|

sues devoid of muscle. |

|

|

• Primary refluxing megaureter: |

|

|

|||

• A bulky peri-ureteric sheath |

|

– Primary refluxing megaureter results from |

|||||||

• A thick sleeve of muscle forming a con- |

an abnormal vesico-ureteric junction, |

||||||||

|

tinuous layer surrounding the muscle |

which impedes the normal anti-reflux |

|||||||

|

bundles of the terminal ureter. The mus- |

mechanisms. |

|

|

|

||||

|

cle forming this outer layer is distinct in |

– This can be due to: |

|

|

|||||

|

its histological appearance and arrange- |

• A short intravesical ureter |

|

|

|||||

|

ment from the muscle bundles which |

• |

Congenital paraureteric diverticulum |

||||||

|

form the |

ureteric |

muscle |

of the |

• Ureterocoele with or without associated |

||||

|

VUJ. Furthermore, this muscle layer is |

|

duplicated collecting system |

|

|||||

|

very densely innervated by nonadrener- |

• Other derangement of |

the |

vesico- |

|||||

|

gic (immunoreactive to dopamine beta- |

|

ureteric junction |

|

|

||||

|

hydroxylase) nerves |

when |

compared |

– It may be associated with megacystis |

|||||

|

with the smooth muscle coat of the ure- |

megaureter syndrome and prune belly |

|||||||

|

ter. This dense nonadrenergic innerva- |

syndrome. |

|

|

|

||||

|

tion of this muscle collar might cause it |

– The marked increase in collagen and sig- |

|||||||

|

to constrict |

inappropriately, |

impeding |

nificant decrease in smooth muscle could |

|||||

|

urinary flow, and ultimately lead to the |

be a major contributing factor in the patho- |

|||||||

|

development of megaureter. |

|

genesis of refluxing primary megaureter. |

||||||

• The altered peristalsis prevents the free |

– There are a few patients with refluxing pri- |

||||||||

|

outflow of urine and functional obstruc- |

mary megaureter who have the megacystis- |

|||||||

|

tion results. |

|

|

|

megaureter |

association, |

with |

the |

|

– The fact that the distal ureter is the last por- |

characteristics of: |

|

|

||||||

tion of the ureter to develop its muscular |

• |

Bilateral hydroureteronephrosis |

|

||||||

coat and that early muscular differentiation |

• A large thin-walled urinary bladder |

||||||||

is primarily of the circular muscle may |

• |

Bilateral high-grade VUR |

|

|

|||||

explain why the aperistalitic segment affect |

– Another special group of patients with dilated |

||||||||

only the distal segment of the ureter. |

ureters are those with prune-belly syndrome, |

||||||||

7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis |

225 |

|

|

in which the dilated ureters may be caused by reflux or VUJ obstruction, or maybe not refluxing and unobstructed, and categorized according to these characteristics.

–A dysgenetic distal ureteric segment that not only fails to cope within the intramural tunnel but also has ineffective peristalsis is implicated in its pathogenesis.

•Non-refluxing unobstructed primary megaureter:

–This is thought to be the most common cause of primary megaureter in neonates, and even though the vesicoureteric junction is normal, with no evidence of reflux or obstruction the ureter is enlarged.

–Most primary megaureter in neonates fall into this category.

–There is neither reflux nor stenosis of the juxtavesical ureter, but the ureter is dilated beginning at a point just above the bladder.

–The cause of this phenomenon is unknown.

–Several theories were proposed:

•Fetal urine production is four to six times greater before than after delivery. This is because of differences in renal vascular resistance, GFR and concentrating ability.

•This high outflow might contribute to ureteric dilatation in the absence of functionally significant obstruction, as is occasionally seen with diabetes insipidus.

•Another contributing factor appears to be increased compliance of the fetal ureter because of differences in the deposition of type III collagen, elastin and other extracellular matrix proteins.

•Partial or transient anatomical or functional obstructions that spontaneously improve with postnatal development could contribute to proximal ureteric dilatation.

•Persistent fetal ureteric folds or delays in the development of normal ureteric peristalsis may be responsible for such transient obstructions.

•Primary megaureter is not known to be hereditary, but families with more than one affected member have been described.

•Primary megaureter may be associated with renal agenesis, megacalycosis and urolithiasis.

7.4Clinical Presentation

•The widespread use of obstetrical US with concomitant fetal screening resulted in an increase in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital uropathies, including megaureter.

•Currently, about half of the cases of congenital megaureter are asymptomatic and discovered on prenatal US.

•Symptomatic patients commonly present with UTI, fever and abdominal pain.

•Microscopic hematuria is frequent and may occur in the absence of urinary tract infection. This is presumably caused by the disruption of mucosal vessels of the ureter secondary to ureteric distension.

•Hematuria may also be a sign of calculus formation secondary to urinary stasis.

•It is not unusual for the dilated asymptomatic ureter to be noted at the time of abdominal surgery for other reasons.

•Rarely, these patients present late with signs of renal failure.

7.5Investigations and Diagnosis

•The diagnosis of megaureter is based on clinical presentation and ultrasound before and after birth.

•The antenatal diagnosis of megaureter is based on ultrasound showing hydronephrosis.

•The diagnosis is confirmed by postnatal ultrasound.

•Grey-scale ultrasound:

–Grey-scale ultrasound is the initial study obtained in any child in whom a urinary abnormality is suspected.

–It provides useful anatomical detail of the renal parenchyma, collecting system, ureter and bladder.

–Ultrasound offers a baseline of the degree of hydroureteronephrosis that can be used in serial follow-up.

•The finding of a ureter more than 7 mm in diameter confirm the diagnosis of a megaureter.

226 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

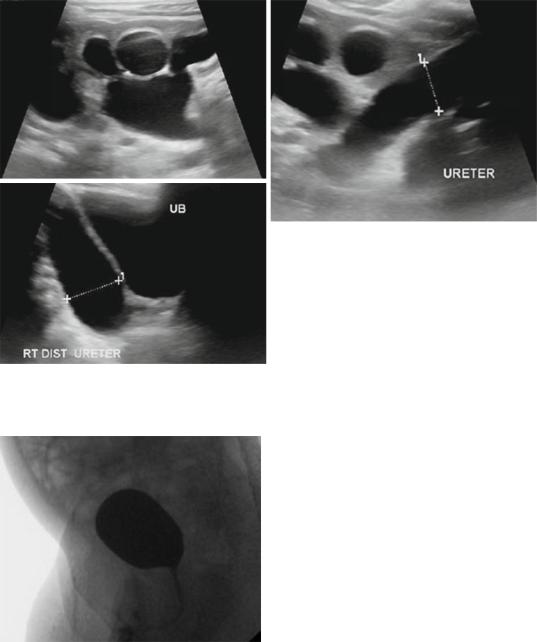

Figs. 7.15, 7.16, and 7.17 Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound showing primary megaureter. Note the markedly dilated ureter

Fig. 7.18 A micturating cystourethrogram of the same patient showing no vesicoureteral reflux

•In obstructive primary megaureter (Figs. 7.15, 7.16, 7.17, and 7.18):

–The ureter tapers to a short segment of normal caliber or narrowed distal ureter, usually just above the vesicoureteric junction (VUJ).

–The distal ureter above this narrowed segment is most dilated.

–There is associated hydronephrosis.

–Active peristaltic waves can be seen on ultrasound.

•The primary nature of megaureter must be confirmed and the secondary causes of megaureter must be excluded.

•Causes of secondary megaureter include:

–Polyuria (diabetes insipidus)

–Infection

–Bladder outlet obstruction

–Neuropathic bladder

–Non-neurogenic voiding dysfunction

–Infravesical obstruction or extrinsic lesions such as posterior urethral valve and severe urethral stricture.

•Doppler ultrasonography:

–Doppler ultrasonography with a measurement of renal resistive index (RI) was recently introduced as a noninvasive method of diagnosing obstructive uropathy.

7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis |

227 |

|

|

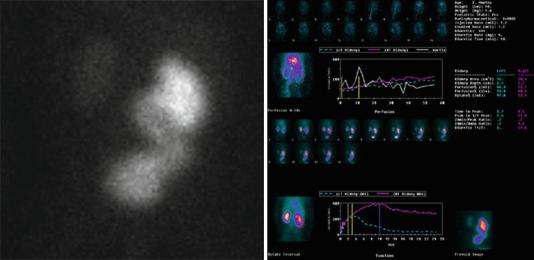

Figs. 7.19 and 7.20 Intravenous urography showing megaureter. Note the dilated ureter and back pressure on the kidney. Note also the tapered lower ureter in the second picture

–It has been shown that the RI is agedependent and is commonly >0.70 in healthy children in the first year of life.

–A normal RI exclude obstruction in the presence of a dilated collecting system.

–An RI threshold of 0.70 gave a sensitivity of 82 %, a specificity of 63 % and an overall accuracy of 76 % in children with obstructive uropathy.

–Several methods have been used to increase the diagnostic accuracy of RI.

–The infusion of normal saline and administration of frusemide significantly decreased the RI of unobstructed kidneys and increased the RI of obstructed units.

–The calculation of the difference between the RI of obstructed and unobstructed kidneys ( RI) strengthens the diagnosis.

– Values of RI of >0.06–0.10 are diagnostic of obstruction.

–Recent reports showed a good correlation between the RI and DR. Therefore, the RI could be used for monitoring the dilated collecting systems under observation, obviating the need for frequent radioisotope scanning.

•The diagnosis is confirmed by intravenous urography (IVU) and radioisotope renography.

•Intravenous urography (IVU) (Figs. 7.19 and 7.20):

–The anatomical detail provided by IVU is useful when the level of obstruction cannot be defined.

–IVU usually shows the pathognomonic configuration of a dilated distal ureteric spindle, a less dilated proximal ureter and a dilated or relatively normal-appearing renal pelvis.

–Caliectasis is either absent or mild.

–IVU is currently rarely used as an initial step in the diagnosis of primary megaureter.

–This is especially in neonates because of renal immaturity and bowel gas.

–IVU should not be used before the age of 3–4 weeks and images taken 1 and 2 h after injection with contrast medium should be obtained.

•Radioisotope renography (Figs. 7.21 and 7.22):

–A renogram provides anatomical information together with objective reproducible variables of both function and obstruction.

228 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

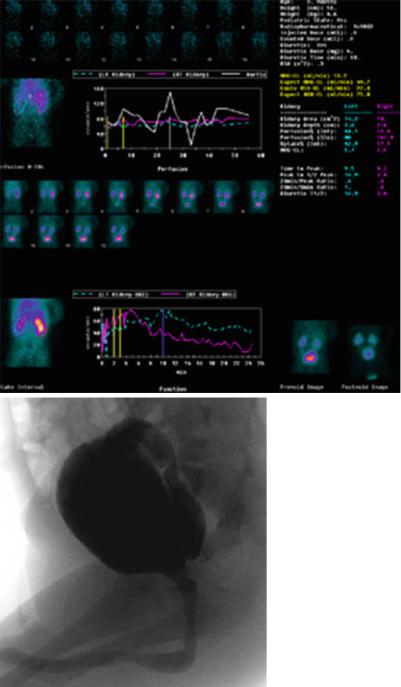

Figs. 7.21 and 7.22 Isotope renogram showing a dilated left ureter (megaureter) with evidence of obstruction

– |

The most commonly used radionuclides |

– Measuring individual renal function to |

|

|

are 99mTc-DTPA and -MAG3. |

detect a decrease in function has been used |

|

– |

To assess obstruction, the diuretic reno- |

by some to show the presence of |

|

|

gram is used to detect the pattern of the |

obstruction. |

|

|

frusemide washout curve and the half-time |

– The critical value of individual renal func- |

|

|

drainage (T1/2). |

tion below which obstruction is considered |

|

– In the standard diuretic renogram, |

has varied among different studies. |

||

|

frusemide is given 20 min after the injec- |

– Values of <30 %, <35 %, or <40 % have |

|

|

tion of tracer. To decrease the false-positive |

been suggested (normal 50 ± 5 %). |

|

|

results this technique was modified and |

– The failure of an expected improvement in |

|

|

frusemide is given 15 min before the injec- |

renal function on further sequential |

|

|

tion of tracer. This is called F-15 instead of |

radionuclide studies could be an indicator |

|

|

the usual F+20 technique. |

of the presence of obstruction. |

|

– Heyman and Duckett described the extrac- |

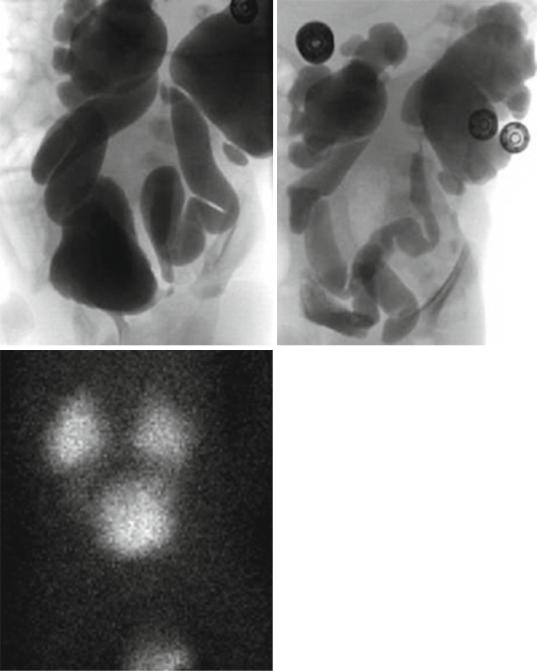

• VUR |

is diagnosed using voiding cystoure- |

|

|

tion factor (EF) as an estimate of single- |

thrography (VCUG) (Figs. 7.23, 7.24, 7.25, |

|

|

kidney function in children during routine |

7.26, and 7.27). |

|

|

radionuclide renography with 99mTc-DTPA. |

– Once ureteric dilatation is detected by US, |

|

– The EF is defined as the percentage uptake |

VCUG is used to exclude reflux, and assess |

||

|

of radionuclide by the kidneys 2–3 min |

the quality of the bladder and urethra. |

|

|

after injection with isotope. |

– In |

refluxing primary megaureter, vesico- |

– The normal mean EF in the new-born is 1.5% |

ureteric reflux is demonstrated. |

||

|

by each kidney, with an increase to 2.5% |

– In non-refluxing unobstructed primary |

|

|

occurring by the end of the first year of life. |

megaureter: |

|

– |

The correlation coefficient of the EF with |

• There is absent or only a minor degree |

|

|

GFR is 0.92. |

|

of hydronephrosis. |

– If renal function is normal by EF and/or equal |

• |

Although rare, congenital megaureter |

|

|

to the contralateral undilated renal unit, the |

|

may co-exist with congenital megacaly- |

|

dilatation seen does not represent a function- |

|

ces, making assessment of hydrone- |

|

ally significant obstructive uropathy. |

|

phrosis more difficult. |

7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis |

229 |

|

|

Figs. 7.23, 7.24, 7.25, 7.26, and 7.27 Micturating cystourethrograms, isotope renography and micturating cystourethrogram of a patient with severe bilateral vesicoureteric reflux but no posterior urethral valve

230 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

Figs. 7.23, 7.24, 7.25, 7.26, and 7.27 (continued)