- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

112 |

4 Renal Tumors in Children |

|

|

–WAGR syndrome. This syndrome includes:

•Wilms tumor.

•Aniridia.

•Abnormalities of the genitals and urinary system.

•Mental retardation.

–Denys-Drash syndrome. This syndrome includes:

•Wilms’ tumor.

•Kidney disease.

•Male pseudohermaphroditism.

•These patients mostly have bilateral or multiple tumors.

–Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. This syndrome includes:

•Omphalocele.

•A large tongue (macroglossia).

•Enlarged internal organs (visceromegaly).

•Hypoglycemia.

4.2.6Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

•Female gender

–Girls are slightly more likely to develop Wilms’ tumor than are boys.

•Black children have a slightly higher risk of developing Wilms’ tumor than do children of other races.

–People of African descent have the highest rates of Wilms’ tumor.

•Children of Asian descent appear to have a lower risk of developing Wilms’ tumor than do children of other races.

•A family history of Wilms’ tumor increases the risk of developing Wilms’ tumor.

•Wilms’ tumor occurs more frequently in children with certain congenital abnormalities, including:

–Aniridia (partial or total absence of the iris)

•A genetic predisposition to Wilms’ Tumor in individuals with aniridia has been established, due to deletions in the p13 band on chromosome 11.

–Hemihypertrophy

–Undescended testicles

–Hypospadias

–A double collecting system

–Horseshoe kidney

•Wilms’ tumor can occur as part of rare syndromes, including:

–WAGR syndrome: This syndrome includes Wilms’ tumor, aniridia, abnormalities of the genitals and urinary system, and mental retardation.

–Denys-Drash syndrome: This syndrome includes Wilms’ tumor, kidney disease and male pseudohermaphroditism.

–Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS):

•BWS is an overgrowth syndrome characterized by visceromegaly, macroglossia, omphalocele and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia.

•Patients with BWS are predisposed to have several embryonal neoplasms, including Wilms’ tumor.

•Few candidate loci for Wilms’ tumor and BWS have been proposed. These loci include the insulinlike growth factor II gene (IGFII), H19 (for an untranslated ribonucleic acid [RNA]), and that encoding for p57kip2.

•WT1 gene:

–WT1, the first Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene at chromosomal band 11p13, was identified as a direct result of the study of children with Wilms’ tumor who also had aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and mental retardation (WAGR syndrome).

–WT1 encodes a transcription factor critical to normal renal and gonadal development.

–The WT1 gene is the specific target of mutations and deletions in a subset of patients with sporadic Wilms’ tumors, as well as in the germline of some children (e.g., those with Denys-Drash syndrome) with a genetic predisposition to develop this cancer.

•Additional genetic loci:

–A second gene that predisposes individuals to develop the Wilms’ tumor has been identified (but has not yet been cloned) telomeric of WT1, at 11p15. This locus was proposed on the basis of studies in patients with both Wilms’ tumor and BeckwithWiedemann syndrome (BWS), another

4.2 Wilms’ Tumor |

113 |

|

|

congenital Wilms’ tumor predisposition syndrome linked to chromosomal band 11p15.

–Loci at 16q, 1p, 7p, and 17p have also been implicated in the biology of Wilms tumor, although these loci do not seem to predispose individuals to develop a Wilms’ tumor. Instead, they seem to be associated with the phenotype or the outcome.

•Wilms tumor may be part of a genetic syndrome and certain birth defects can also increase a child’s risk for developing Wilms tumor.

•The following genetic syndromes and birth defects have been linked to Wilms tumor:

–WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, aniridia, abnormal genitourinary system, and mental retardation)

–Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (visceromegaly, macroglossia, and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia)

–Hemihypertrophy

–Denys-Drash syndrome

–Cryptorchidism

–Hypospadias

•It is recommended that children with these genetic syndromes and birth defects should be screened for Wilms tumor every 3 months until age 8 years.

4.2.7Staging of Wilms Tumor

•Staging of Wilms tumor is based on anatomical findings and tumor cells pathology.

•The Children’s Oncology Group staging of Wilms tumors:

•Stage I (43 % of patients)

–Tumor is limited to the kidney and is completely excised.

–The surface of the renal capsule is intact.

–The tumor is not ruptured or biopsied (open or needle) prior to removal.

–No involvement of extrarenal or renal sinus lymph-vascular spaces

–No residual tumor apparent beyond the margins of excision.

–Metastasis of tumor to lymph nodes not identified.

•Stage II (23 % of patients)

–Tumor extends beyond the kidney but is completely excised.

–No residual tumor apparent at or beyond the margins of excision.

–Any of the following conditions may also exist:

•Tumor involvement of the blood vessels of the renal sinus and/or outside the renal parenchyma.

•The tumor has been biopsied prior to removal or there is local spillage of tumor during surgery, confined to the flank.

•Extensive tumor involvement of renal sinus soft tissue.

•Stage III (20 % of patients)

–Inoperable primary tumor.

–Lymph node metastasis.

–Tumor is present at surgical margins.

–Tumor spillage involving peritoneal surfaces either before or during surgery, or transected tumor thrombus.

•Stage IV (10 % of patients)

–Stage IV Wilms tumor is defined as the presence of hematogenous metastases (lung, liver, bone, or brain), or lymph node metastases outside the abdomenopelvic region (Fig. 4.19).

•Stage V (5 % of patients)

–Stage V Wilms tumor is defined as bilateral renal involvement at the time of initial

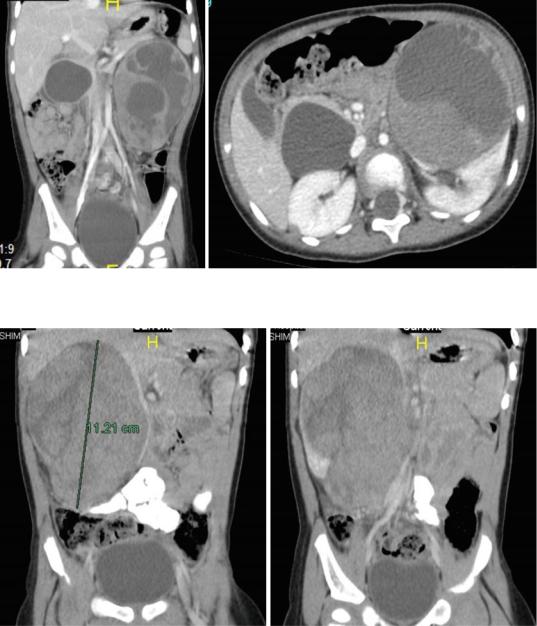

diagnosis (Figs. 4.20 and 4.21).

–In term of treatment and prognosis, for patients with bilateral Wilms tumor, it is important to stage each side separately according to the above criteria on the basis of extent of disease and plan treatment according to the side with the more advanced stage.

•The National Wilms Tumor Study Group (NWTSG) and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) have contributed to the overall improved survival of children with Wilms tumors. They improved our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the development of Wilms tumor and identified several chemotherapeutic agents through clinical trials.

114 |

4 Renal Tumors in Children |

|

|

•Children with bilateral Wilms tumor are treated with preoperative chemotherapy. This is important because each kidney is staged separately, and preoperative chemotherapy may lead to complete resolution of disease in one kidney or reduction in the size of both tumors. This will make it possible to subsequently do nephrectomy on one side only or bilateral partial nephrectomies.

4.2.8Investigations

•It is important to investigate children with Wilms tumor.

Fig. 4.19 CT-scan of the chest showing secondaries from Wilms tumor

•The aim of the specific investigations is to evaluate the:

–Site

–Size

–Extent of the tumor

–Presence or absence of secondaries

–Presence or absence of synchronous Wilms tumors

–It is also important to make sure that there is a normally functioning contralateral kidney

•There are general and specific investigations.

•The general investigations include:

–A complete blood count

–Electrolytes

–Liver function tests

–BUN and creatinine

–Urinalysis

–Coagulation studies

–Serum calcium

•It is of great importance to exclude extension of the tumor into the renal vein as well as the inferior vena cava.

• A plain abdominal radiograph (KUB) (Figs. 4.22 and 4.23):

–This often shows a soft tissue density with displacement of bowel loops inferiorly and to the contralateral side.

–Occasionally calcification (<10 %) is seen.

Figs. 4.20 and 4.21 Abdominal CT-scan in two patients with bilateral Wilms’ tumor. The sizes of both tumors is different

4.2 Wilms’ Tumor |

115 |

|

|

Figs. 4.22 and 4.23 Abdominal radiograph showing a soft tissue density in two patients with right and left Wilms tumor. Note the mass compressing and pushing the bowel downward and to the other side

–The calcification usually is located on the edge of the tumor whereas calcification in neuroblastoma is speckled throughout.

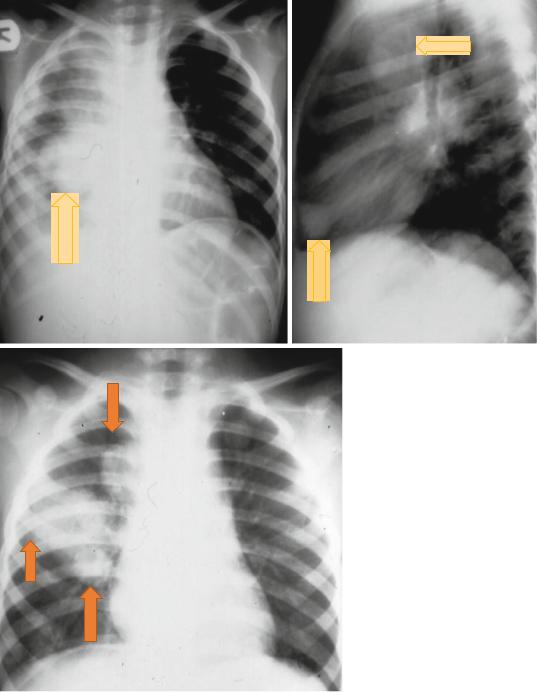

•Chest radiograph (Figs. 4.24, 4.25, and 4.26):

–This is to confirm or exclude the presence of secondaries in the lungs.

–Distant metastasis in Wilms’ tumor is commonly seen in the lungs.

–CT-scan of the chest is more informative for the presence or absence of secondaries.

–In children with Wilms’ tumor. CT-scan of the chest and abdomen should be done simultaneously.

–Abnormalities seen on chest CT-scan however, needs to biopsied to confirm the diagnosis.

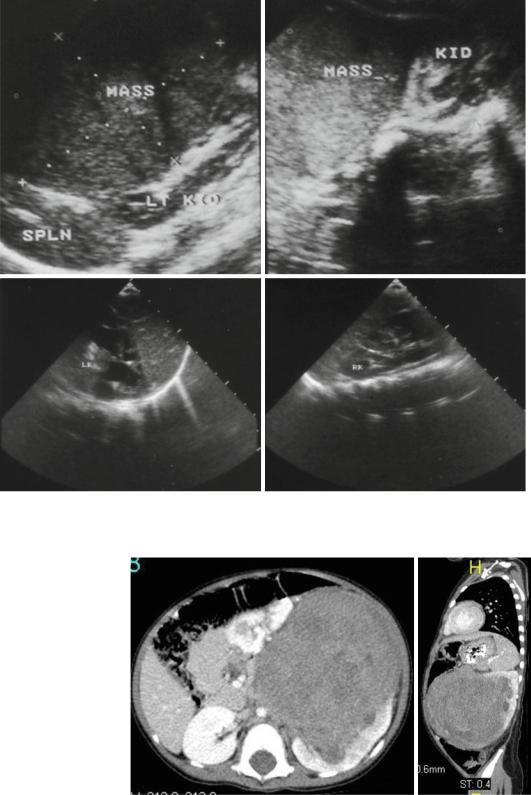

•Abdominal ultrasound (Figs. 4.27, 4.28, 4.29, and 4.30):

–This is valuable in determining the origin of the tumor, whether the mass is cystic or solid; and indicates if the tumor extends into the renal veins and inferior vena cava.

–It is also useful in evaluating the contralateral kidney and whether a synchronous tumor is present or not.

–Doppler ultrasound is a valuable investigation in detecting tumor extension in the renal vein and inferior vena cava and the extent of extension.

–This shows a solid intrarenal mass.

–The mass has heterogeneous echogenicity, which represents hemorrhage, fat, necrosis, or calcification.

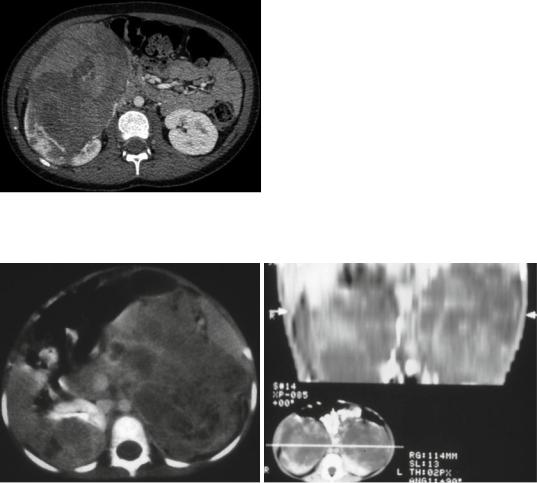

•Abdominal and thoracic CT-scan (Figs. 4.31, 4.32, 4.33, 4.34, and 4.35):

–This defines the tumor site; identifies the presence of enlarged lymph nodes; evaluates the contralateral kidney for possible presence of a second Wilms’ tumor; assesses extension of the tumor into the

renal veins, inferior vena cava and right atrium, and determines if the patient has intra-abdominal secondaries to the liver.

–It is also valuable in detecting nodal metastases as well hemorrhage and areas of calcification within the tumor.

–It is important to visualize the contralateral kidney and document that it is functioning using contrast.

116 |

4 Renal Tumors in Children |

|

|

Figs. 4.24, 4.25, and 4.26 Chest x-rays showing pulmonary secondaries from Wilms’ tumor

4.2 Wilms’ Tumor |

117 |

|

|

Figs. 4.27, 4.28, 4.29, and 4.30 Abdominal ultrasound showing left renal Wilms tumor in the upper one and bilateral Wilms tumor in the lower two pictures

Figs. 4.31 and

4.32 Abdominal CT-scan showing a very large left Wilms tumor

118 |

4 Renal Tumors in Children |

|

|

–Thoracic CT-scan is important to detect pulmonary metastasis. Sometimes pulmonary metastasis are not seen on chest x-ray and appear only on CT-scan.

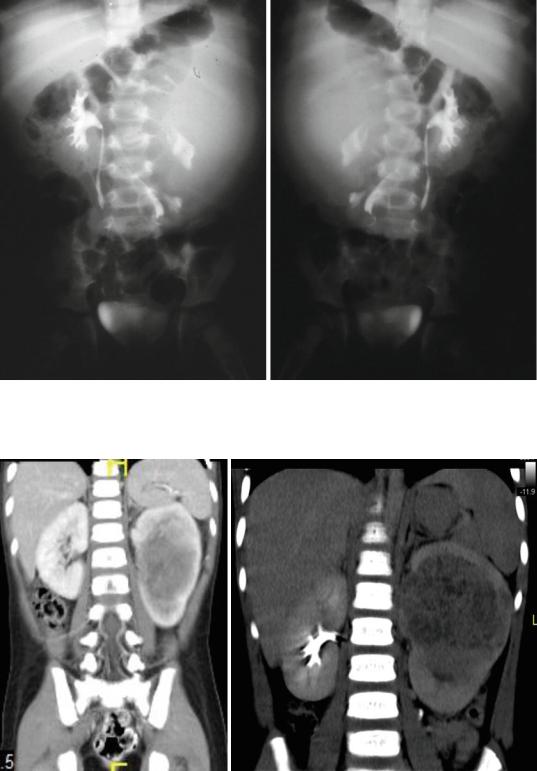

•Intravenous urography (Figs. 4.36, and 4.37):

–In the past, this was one of the radiological investigation used to evaluate children with Wilms’ tumor.

–This is also useful to show that a normal functioning contralateral kidney is present.

–Currently, this is replaced by CT-scan and MRI.

•MRI scanning (Figs. 4.38, 4.39, 4.40, 4.41, 4.42, and 4.43):

–Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reportedly the most sensitive

Fig. 4.33 Abdominal CT-scan showing a very large right Wilms tumor

imaging modality for determination of caval patency and may be important in determining whether the inferior vena cava is directly invaded by the tumor or not.

–Wilms’ tumor demonstrates low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

•Tumor extension into the renal vein and IVC is seen in 5–10 % of patients with Wilms tumor.

•A cystic variant of Wilms tumor may mimic benign multilocular cystic nephroma.

•Small abnormalities seen on chest x-ray are suggestive of secondaries but those seen on CT-scan may need to be confirmed by biopsy.

•With the current radiological investigations, physical inspection of the opposite kidney by opening Gerota’s fascia as suggested previously to check for synchronous tumor is no longer necessary.

•Abdominal and chest CT-scan is useful in determining (Figs. 4.44, 4.45, 4.46, 4.47, 4.48, 4.49, 4.50, and 4.51):

–The origin of the tumor

–Involvement of the regional lymph nodes and local recurrence

–Bilateral renal involvement

–To visualize the contralateral kidney and document that it is functioning using contrast.

–Invasion into the renal vein and inferior vena cava

–Liver metastases

–Lung metastases

Figs. 4.34 and 4.35 Abdominal CT-scans showing bilateral Wilms tumor

4.2 Wilms’ Tumor |

119 |

|

|

Figs. 4.36 and 4.37 Intravenous urography showing left and right Wilms tumors. Note the normal functioning contralateral kidney. Note also the distortion of the calcyeal system of the affected kidney

Figs. 4.38 and 4.39 Abdominal MRI showing left Wilms tumor. Note the normally functioning right kidney

120 |

4 Renal Tumors in Children |

|

|

•Diagnostic biopsy of lesions noted on the chest CT scan is recommended to confirm the diagnosis.

•Histopathologic confirmation of Wilms tumor is essential.

•Transcutaneous biopsy is not usually recommended as this may complicate treatment by

causing preoperative tumor spill, requiring whole abdominal radiotherapy.

–The National Wilms Tumor Study Group (NWTSG):

•Patients with unilateral Wilms tumor undergo nephrectomy immediately.

Figs. 4.40 and 4.41 Abdominal MRI showing a large left side Wilms’ tumor with areas of hemorrhage and or necrosis. Note also an associated congenital pancreatic cyst

Figs. 4.42 and 4.43 Abdominal MRI showing a large right side Wilms’ tumor