- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

372 |

13 Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex |

|

|

13.5.11 Complications

•The most common complications of both Cantwell-Ransley and complete penile disassembly epispadias repair are persistent chordee, urethrocutaneous fistula, and wound dehiscence.

•A complication specific to the Mitchell repair’s complete disassembly technique is glans and/or corporeal ischemia.

•Complications following repair of bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy include:

–Wound dehiscence

–Bladder prolapse

–Bladder outlet obstruction

–Vesicocutaneous fistula

•Complete primary repair of exstrophy may be complicated by penile loss following penile disassembly.

•Intestinal complications following repair of cloacal exstrophy include;

–Ileus

–Volvulus

–Small bowel obstruction

•Augmentation cystoplasty and continent urinary diversion may be complicated by:

–Bladder calculi

–Chronic bacterial colonization

–Epithelial polyps

–Mucus overproduction

–Augmentation cystoplasty may be complicated by metabolic acidosis and carcinoma

–The creation of stoma may be complicated by stenosis, prolapse, ischemia, and leakage

Further Reading

1.Baird AD, Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Applications of the modified Cantwell-Ransley epispadias repair in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Pediatr Urol. 2005;1(5):331–6.

2. Frimberger D. Diagnosis and management of epispadias. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2011;20(2):85–90.

3. Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. The use of parenteral testosterone therapy in genital reconstructive surgery. J Urol. 1987;138(4):1077–8. Part 2.

4. Gearhart JP, Leonard MP, Burgers JK, Jeffs RD. The Cantwell-Ransley technique for repair of epispadias. J Urol. 1992;148(3):851–4.

5. Gearhart JP, Mathews R. Penile reconstruction combined with bladder closure in the management of classic bladder exstrophy: illustration of technique. Urology. 2000;55(5):764–70.

6.Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Exstrophy-epispadias complex. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-walsh urology, vol.

4.10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 3325–78.

7.Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Complete primary repair of exstrophy. J Urol. 1999;162(4):1415–20.

8.Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Management of epispadias. Urol Clin N Am. 2002;29(2):349–60.

9.Mathews R. Achieving urinary continence in cloacal exstrophy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2011;20(2):126–9.

10.Mitchell ME. Bladder exstrophy repair: complete primary repair of exstrophy. Urology. 2005;65(1):5–8.

11.Mitchell ME, Bägli DJ. Complete penile disassembly for epispadias repair: the mitchell technique. J Urol. 1996;155(1):300–4.

12. Mushtaq I, Garriboli M, Smeulders N, et al. Primary neonatal bladder exstrophy closure in neonates: challenging the traditions. J Urol. 2014;191(1):193–8.

13. Oesterling JE, Jeffs RD. The importance of a successful initial bladder closure in the surgical management of classical bladder exstrophy: analysis of 144 patients treated at the Johns Hopkins hospital between 1975 and 1985. J Urol. 1987;137(2):258–62.

14. Schaeffer AJ, Stec AA, Purves JT, Cervellione RM, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy: a single institution referral experience. J Urol. 2011;186(3):1041–6.

15.Shnorhavorian M, Grady RW, Andersen A, Joyner BD, Mitchell ME. Long-term follow-up of complete

primary repair of exstrophy: the seattle experience. J Urol. 2008;180(4, supplement):1615–20.

16. Suson KD, Preece J, Baradaran N, Di Carlo HN, Gearhart JP. The fate of the complete female epispadias and female exstrophy bladder—is there a difference? J Urol. 2013;190(4):1583–9.

17. Zaontz MR, Steckler RE, Shortliffe LMD, Kogan BA, Baskin L, Tekgul S. Multicenter experience with the Mitchell technique for epispadias repair. J Urol. 1998;160(1):172–6.

Megacystis Microcolon Intestinal |

14 |

Hypoperistalsis Syndrome (Berdon |

Syndrome)

14.1Introduction

•Berdon syndrome, also called Megacystis- microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIH syndrome), is an autosomal recessive fatal genetic disorder affecting newborns.

•It is a familial disturbance of unknown etiology.

•It was first described by Walter Berdon et al. in 1976.

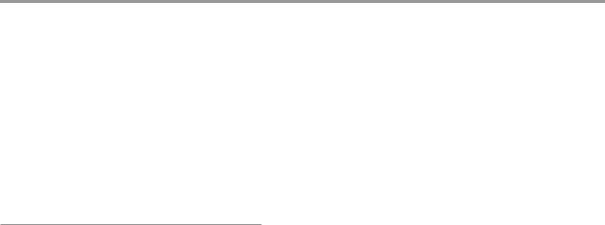

•They described the condition in five female infants, two of whom were sisters. All had marked dilatation of the bladder and some had hydronephrosis and the external appearance of prune belly. The infants also had microcolon and dilated small intestines (Fig. 14.1).

•Megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS) is the most severe form of functional intestinal obstruction in the newborn.

•The etiology of MMIHS is unknown.

•Megacystis Microcolon Intestinal Hypoperistalsis Syndrom (MMIHS) is found in females three or four times more than in males.

•It is characterized by (Figs. 14.2, 14.3, 14.4, 14.5, and 14.6):

–A dilated, giant non obstructed urinary bladder (megacystis)

–Urinary retention

–Microcolon

–Hypoperistalsis or absent peristalsis of the gastrointestinal tract leading to functional intestinal obstruction.

–Hydronephrosis

–Dilated small bowel

–The pathological findings consist of an abundance of ganglion cells in both dilated and narrow areas of the intestine.

•MMIHS carries a poor prognosis and most of the cases die within the early months of their lives, nevertheless there are some case reports recently of long-term survival.

•These cases mostly die from malnutrition, sepsis, kidney failure, and liver failure depending on TPN and the complications of TPN.

•In 2011 and in an extensive review of 227 children with the MMIHS, Gosemann and Puri reported a 19.7 % survival rate and the oldest reported survivor was 24 years old. The vast majority of the surviving patients had to be maintained by total or partial parenteral nutrition (TPN). The main causes of death were sepsis, malnutrition and multiple organ failure.

•Prenatal diagnosis of MMIHS is possible by antenatal ultrasound and an antenatal ultrasound finding of an enlarged urinary bladder and intraabdominal mass in a female fetus should alert the treating physicians for MMIHS.

•The usual presentation of newborns with MMIHS is abdominal distension. This is caused by a markedly distended, but nonobstructed urinary bladder. This usually fills the whole abdomen and may reach to the xiphisternum.

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017 |

373 |

A.H. Al-Salem, An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_14 |

|

374 |

14 Megacystis Microcolon Intestinal Hypoperistalsis Syndrome (Berdon Syndrome) |

|

|

Fig. 14.1 A micturating cystourethrogram showing a markedly enlarged urinary bladder. Note also the dilated stomach. There was no evidence of vesicoureteral reflux

DILATED

STOMACH

DILATED

URINARY

BLADDER

DILATED URINARY

BLADDER

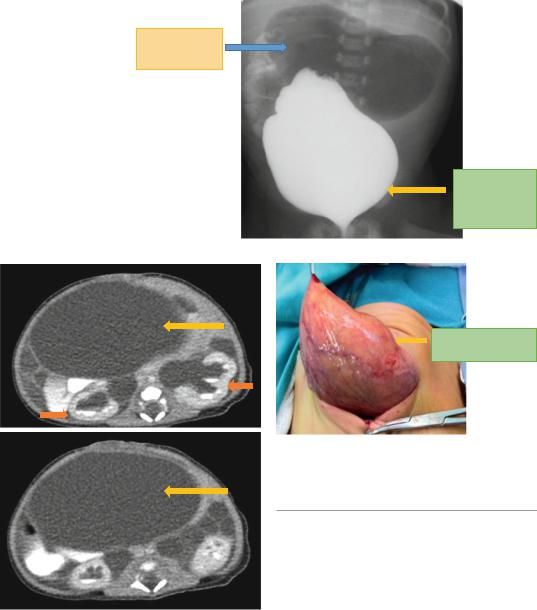

Figs. 14.2 and 14.3 Abdominal CT-scans showing a markedly dilated urinary bladder. Note also the associated bilateral hydronephrosis

•Treatment is supportive and involves an ileostomy to defunction the colon, with TPN.

•Multiorgan transplantation is suggested as a valuable alternative for children with severe gastrointestinal dismotility.

Fig. 14.4 An intraoperative clinical photograph showing a markedly dilated urinary balder. Note the thick wall of the enlarged urinary bladder

14.2Etiology

•MMIHS is a rare congenital anomaly inherited as an autosomal recessive and predominantly affects females (4:1 ratio).

•There are however reports of sporadic cases.

•MMIHS is inherited as an autosomal recessive with the gene locus at 15q11.

•The exact etiology of MMIHS is not known.

•There are several theories to explain its pathogenesis but the most commonly accepted etiology is that MMIHS is a form of visceral myopathy.

•This was supported by histological studies which showed smooth muscle myopathy as

14.2 Etiology |

375 |

|

|

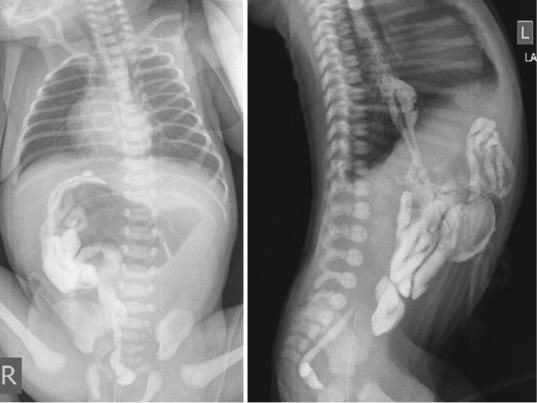

Figs. 14.5 and 14.6 Lower contrast enema showing small unused microcolon

the most predominant intestinal manifestation. This affects both the circular and longitudinal layers of the small bowel muscularis propria.

•Histological studies of the myenteric and submucosal plexuses of the bowel of MMIHS patients have found normal ganglion cells in the majority of the patients, decreased in some, hyperganglionosis and giant ganglia in others.

•An imbalance in intestinal peptides was suggested as one of the possible causes of hypoperistalsis.

•Absence of Interstitial Cell of Cajal (Pacemaker cells) in the bowel and urinary bladder has been reported as a causative factor.

•Puri and coworkers showed vacuolar degenerative changes in the smooth muscle cells with abundant connective tissue between muscle cells in the bowel and bladder.

•Several subsequent reports have confirmed evidence of intestinal myopathy in MMIHS.

•MMIHS has been reported with excessive smooth muscle glycogen storage postulating the pathogenesis involving a defect of glycogen-energy utilization.

•Other investigators have reported absence or marked reduction in smooth muscle actin and other contractile and cytoskeletal proteins in the smooth muscle layers of bowel in MMIHS

•Molecular analysis have linked the disease to the

neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (ηAChR), namely the absence of a functional α3 subunit of the ηAChR, a de novo deletion of the

proximal long arm of chromosome 15 (15q11.2).

•Immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle actin, however, was selectively absent in the circular layer, demonstrating isolated absence in a unique and previously undescribed pattern. These observations raise the