- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

Persistent Müllerian Duct |

10 |

Syndrome (PMDS) |

10.1Introduction

•Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is a rare disorder of sexual development.

•It was first described by Nilson in 1939.

•It is also called persistent oviduct syndrome.

•It is considered by some to be a form of pseudohermaphroditism due to the presence of Müllerian derivatives.

•This syndrome is characterized by the persistence of Mullerian duct derivatives (i.e. uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and upper two thirds of vagina) in a phenotypically (normal male reproductive organs and normal male external genitalia) and karyotypically (46, XY) male patient.

•Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome is usually caused by deficiency of fetal anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) effect due to mutations of the gene for AMH or the anti-Müllerian hormone receptor, but may also be as a result of insensitivity to AMH of the target organ.

•PMDS is caused by mutations in the AMH gene (PMDS type 1) or AMHR2 gene (PMDS type 2) and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

•It affects males who have normal chromosomes (46, XY) and have normal male reproductive organs and normal male external genitalia.

•Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome affects only males and is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern.

•Affected males with this disorder have normal male reproductive organs. They also have internal female reproductive organs (a uterus and fallopian tubes).

•The clinical features of PMDS depends on the mobility of the Müllerian derivatives (the uterus and fallopian tubes) which leads to either cryptorchidism or inguinal hernia. If the uterus and fallopian tube are mobile, they may descend into the inguinal canal during testicular descent. However, if the Müllerian derivatives are relatively immobile testicular descent may be impeded and the patient presents with undescended testes either unilateral or bilateral.

10.2Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

•The normal sexual differentiation depends on the genetic sex (XX or XY), which is established at the time of conception.

•Following conception, the fetus is sexually indifferent with two different bipotential gonads and two pairs of internally developing Wolffian and Müllerian ducts.

•These two undifferentiated bipotential gonads develop from the urogenital ridge and ultimately develop into either a testis or an ovary.

•In addition to these bipotential gonads, fetuses of both sexes have also two sets of internal ducts: the Müllerian ducts and the Wolffian

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017 |

287 |

A.H. Al-Salem, An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_10 |

|

288 |

10 Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome (PMDS) |

|

|

ducts which develop by 6–7 weeks of intrauterine life.

•Expression of sex-determining genes on the early bipotential gonad promotes development of the gonad into either a testis or an ovary.

•Various genes expressed by the Y chromosome at very specific times during development are responsible for the differentiation of the testes.

•In a male fetus, the testis differentiates by the end of the seventh gestational week.

•A 35-kilobase (kb) gene determinant located on the distal short arm of the Y chromosome, known as the SRY (sex determining region of the Y chromosome) is responsible for initiating the indifferent gonads to develop into testes.

•SRY codes for a transcription factor that acts in the somatic cells of the genital ridge.

•Expression of this gene triggers a cascade of events that ultimately leads to the development of testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells.

•SRY expression directs testicular morphogenesis, leading also to the production of MIS (Müllerian-inhibiting substance), and, later, testosterone.

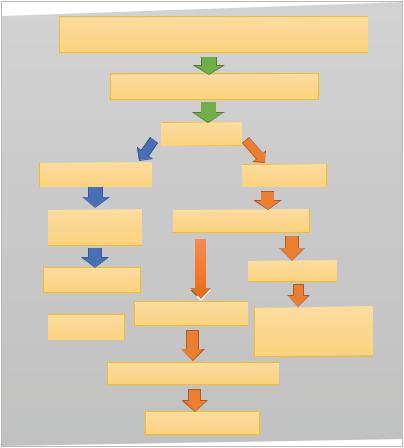

•Normal sex differentiation is controlled by:

–Testosterone

–Dihydrotestosterone

–Müllerian Inhibiting Factor (MIF).

–Sertoli cells secrete MIF, which leads to regression of the Müllerian ducts.

–Leydig cells secret testosterone which has a direct effect on the Wolffian ducts, and promotes their differentiation into the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles.

–Testosterone and under the influence of 5-alpha reductase is converted to Dihydrotestosterone which induces male differentiation of external genitalia.

–Patients with PMDS have both Wolffian and Müllerian duct structures due to a deficiency of MIF.

•The external genitalia at 6–7 weeks gestation appear female and include a genital tubercle,

the genital folds, urethral folds and a urogenital opening. These subsequently differentiate into male or female external genitalia under the influence of estrogen or dihydrotestosterone.

•Male Differentiation:

–The male sexual differentiation depends on two important steps:

•The development of the bipotential gonad into a testis.

•Internal and external genitalia differentiation.

–The development of the bipotetial gonad into a testis occurs at about the sixth week of gestation under the influence of the SRY gene.

•The SRY gene is located on the short arm of the Y-chromosome (Yp11.3). It is responsible for initiating sex differentiation by downstream regulation of sexdetermining factors.

•This involves expression of several genes including WT1, CBX2 (M33), SF1, GATA4/FOG2 is critical to SRY activation.

•The SOX9 gene, located on 7q24.3- 25.1, is essential for early testis development.

–The second step in male sex differentiation involves internal and external genitalia differentiation.

–The developed testes have two types of cells:

•The Leydig cells

•The Sertoli cells

–The Sertoli cells produce the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH).

–The Leydig cells produce testosterone.

–The AMH acts on its receptor in the Müllerian ducts and causes their regression.

–Testosterone acts in a critical concentrationdependent and time-dependent manner to induce male sexual differentiation.

–Testosterone acts on the androgen receptor in the Wolffian ducts to induce the formation of:

•Epididymis

10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome |

289 |

|

|

•Ejaculatory ducts

•Seminal vesicles.

–The Leydig cells also produce insulin-like factor 3 (INSL3, relaxin-like factor), which play a role in the descent of testes to the scrotum.

–Testesterone is also converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) under the influence of 5-alpha reductase enzyme, which acts on the androgen receptor of the prostate and external genitalia to cause its masculinization.

–Binding of Testosterone and DHT to androgen receptors is necessary for androgen effect.

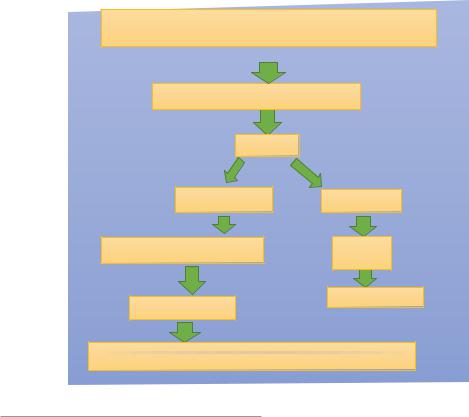

•Female Differentiation:

–In females and as a result of the absence of SRY gene, the bipotential gonad develops into an ovary.

–DAX1 gene is necessary for both testicular and ovarian development.

–WNT4-signaling pathway plays a major role in ovarian development, Müllerian ducts development and ovarian steroidogenesis.

–The second step in female sex differentiation involves internal and external genitalia differentiation.

–Absence of the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) which is secreted by the testes leads to development of the Müllerian ducts.

The SRY gene (located on the short arm of the Y- chromosome (Yp11.3))

Bipotential gonad (Indifferent gonad)

|

Testis |

Sertoli cells |

Leydig cells |

Anti-Mullerian |

Testosterone |

hormone |

|

Mullerian ducts |

Wollfian ducts |

|

Dihdrotestosterone Epididymis Regression Ejaculatory ducts

Dihdrotestosterone Epididymis Regression Ejaculatory ducts

Seminal vesicles

Prostate and external

Masculinization

290 |

10 Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome (PMDS) |

|

|

–The Müllerian ducts give rise to:

•The fallopian tubes

•Uterus

• The upper two-third of the vagina

–Absence of testesterone leads to regression of the Wollfian ducts.

–Estrogen secreted by the developing ovary leads to the development of the external genitalia of the female.

–In the female, the genital tubercle becomes the clitoris, the labio-scrotal folds become the labia majora, and the urethral folds become the labia minora.

Absence of the SRY gene (located on the short arm of the Y- chromosome (Yp11.3)

Bipotential gonad (Indifferent gonad)

Ovary |

|

No Sertoli cells |

Estrogen |

No Anti-Mullerian hormone |

External |

|

Genitalia |

Mullerian ducts |

Feminization |

|

The fallopian tubes, Uterus, The upper two-third of the vagina

10.3Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

•This condition is usually caused by deficiency of fetal anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) effect due to mutations of the gene for AMH or the anti-Müllerian hormone receptor, but may also be as a result of insensitivity to AMH of the target organ.

•AMH (Anti Müllerian Hormone) is produced by the primitive Sertoli cells as one of the earliest Sertoli cell products and induces regression of the Müllerian ducts.

•Fetal Müllerian ducts are only sensitive to AMH action around the seventh or eighth

week of gestation, and Müllerian regression is completed by the end of the ninth week.

•The AMH induced regression of the Müllerian duct occurs in cranio-caudal direction via apoptosis.

•The AMH receptors are on the Müllerian duct mesenchyme and transfer the apoptotic signal to the Müllerian epithelial cell, presumably via paracrine actors.

•The Wolffian ducts differentiate into epididymis, vasa differentia and seminal vesicles under the influence of testosterone, produced by the fetal Leydig cells.

•Most people with persistent Müllerian duct syndrome have mutations in the AMH gene or the AMHR2 gene.