- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

Congenital Megaureter |

7 |

|

7.1Introduction

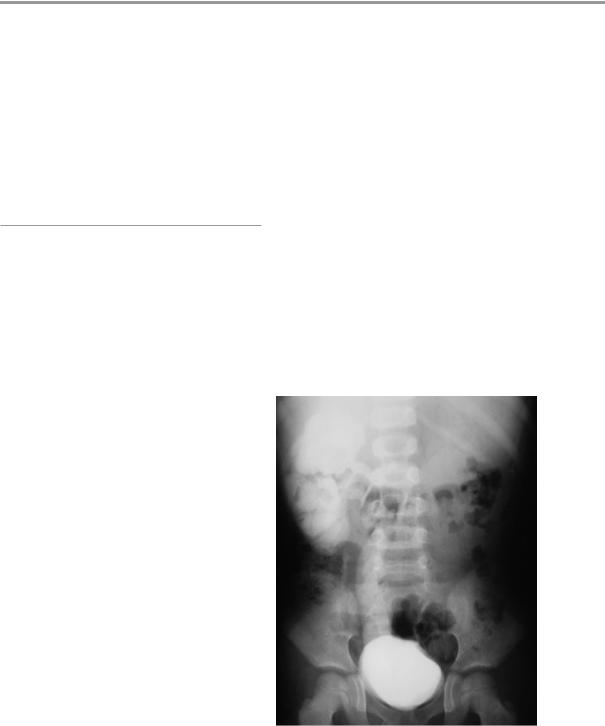

•The term megaureter refers to an enlarged dilated ureter (Fig. 7.1).

•In children, any ureter greater than 7 mm in diameter is considered a megaureter.

•The megaureter is divided into two main groups depending on etiology:

–Primary megaureter:

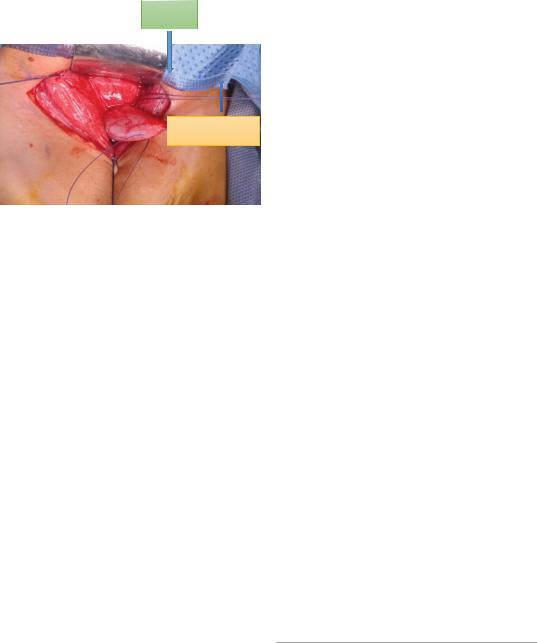

•This results from a functional or anatomical abnormality involving the ureterovesical junction (Fig. 7.2).

–Secondary megaureter:

•This results from abnormalities that involve the bladder or urethra including:

–Myelomeningocele/neurogenic bladder

–Severe urethral stricture

–Posterior urethral valves

•Primary megaureter is further sub classified according to the presence or absence of reflux and obstruction.

•Megaureter is divided into four types:

–Refluxing megaureter

–Obstructed megaureter

–Refluxing/obstructed megaureter

–Non-refluxing/ non-obstructed megureter

•Each of these types is further subdivided into primary or secondary:

–This is based on either intrinsic or extrinsic causes for their appearance.

•Bilateral involvement is present in about 20% of patients with primary obstructed megaureter.

•The left side is more commonly affected than the right (1.6–4.5 times).

•Primary obstructed megaureter is more common in males with male-to-female ration of about 4:1.

•Congenital primary megaureter is an idiopathic condition in which the bladder and bladder outlet are normal but the ureter is dilated.

Fig. 7.1 Intravenous urography showing a right megaureter. Note the markedly dilated ureter causing back pressure on the kidney

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017 |

217 |

A.H. Al-Salem, An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_7 |

|

218 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

DILATED

URETER

NARROW DISTAL

URETERIC SEGMENT

Fig. 7.2 A clinical intraoperative photograph showing a primary megaureter. Note the small narrowed distal ureteric segment which is aperistalitic

•Primary megaureter is the second most common cause of neonatal hydronephrosis.

•The majority of cases are non-refluxing and unobstructed.

•The incidence of obstructed megaureter is 1 in 10,000 live newborns.

•Most primary megaureter in neonates is nonrefluxing and unobstructed.

–The etiology of this is unknown

–It may be due to high fetal urine outflow

–It may be caused by changes in the ureter preand postnatal or transient anatomical obstructions that improve with postnatal development, such as ureteral folds.

•In unilateral primary megaureter the contralateral kidney is absent or dysplastic in 10–15 % of patients.

•About 50 % of primary megaureter cases are asymptomatic and are discovered on routine antenatal ultrasound.

•Most asymptomatic patients have unobstructed primary megaureter.

•Symptomatic primary megaureter present with:

–Urinary tract infections

–Hydronephrosis

–Fever

–Abdominal and flank pain

–Microscopic hematuria is frequent and may occur without infection.

–The presence of microscopic hematuria may indicate calculus formation.

–These patients rarely present with signs of renal failure.

•Vesicoureteric reflux disease (VUR): although actually a cause of primary congenital megaureter it is usually considered separately as prognosis and treatment, depending on degree of reflux, is different

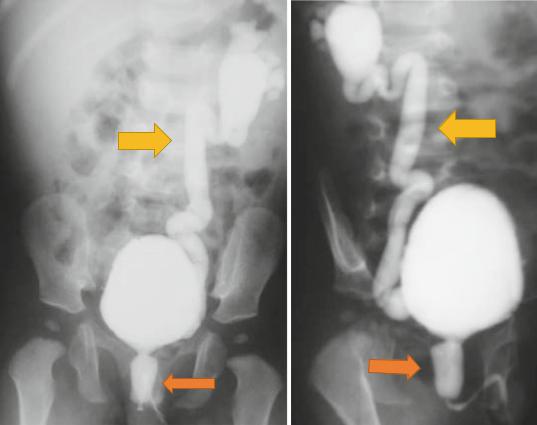

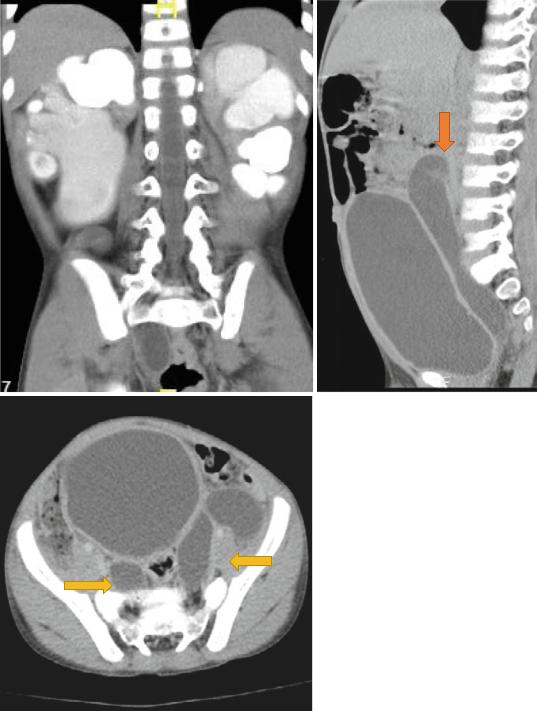

•Causes of secondary megaureter include (Figs. 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, 7.7, 7.8, 7.9, 7.10, 7.11, 7.12, 7.13, and 7.14):

–Posterior urethral valve: This is often associated with bilateral hydroureter/ hydronephrosis

–Ureteral diverticulum

–Urolithiasis

–Urotrocele

–Duplex collecting system with reflux into lower pole moiety

–Myelomeningocele/neurogenic bladder

–Severe urethral stricture

•Primary megaureter is a common cause of obstructive uropathy among neonates and young children.

•It is estimated that vesico-ureteric junction obstruction account for 23 % of neonates diagnosed with obstructive uropathy.

•Children presenting before 1 year old are more likely to have bilateral Primary megaureter than are older patients.

•The condition is not known to be hereditary, but families with more than one member with PM have been described.

7.2Classification

•The term ‘megaureter’ could be applied to any dilated (mega) ureter.

•In general use, the term megaureter is not applied to a hydroureter caused by overt

7.2 Classification |

219 |

|

|

Figs. 7.3 and 7.4 Micturating cystourethrograms showing posterior urethral valves and associated vesicoureteral reflux

neuropathic bladder or typical bladder neck obstruction.

•Megaureter is usually reserved for conditions in which the bladder and bladder outlet are normal but the ureter is dilated.

•Many classifications were proposed for megaureter.

•The international classification of Smith et al. is the most comprehensive classification.

–Obstructed

–Refluxing

–Unobstructed

–None refluxing

•Each of these categories is subdivided into a primary and secondary group.

•In primary megaureter the cause is idiopathic.

•Secondary megaureter may be caused by:

–Urethral obstruction

–Bladder outlet obstruction

–Neurogenic bladder

–Polyuria

–Infection

•A more practical classification of megaureter was given by King as:

–Refluxing

–Obstructed

–Not refluxing

–Not obstructed

–Refluxing and obstructed

220 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

Figs. 7.5, 7.6, and 7.7 CT-urography showing duplex system and bilateral hydroureteronephrosis. Note the dilated megaureters

7.2 Classification |

221 |

|

|

DYSPLASTIC URETROCELE

KIDNEY

MEGAURETER

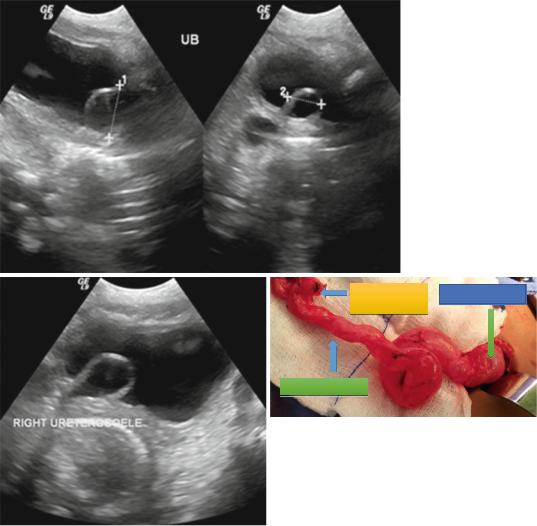

Figs. 7.8, 7.9, and 7.10 Pelvic ultrasound and intraoperative photograph showing uretrocele. Note the markedly dilated ureter

•Primary megaureter usually includes:

–Obstructed primary megaureter

–Unobstructed primary megaureter

•Secondary megaureter is caused by a variety of urological disorders.

•Primary obstructed megaureter:

–This is most commonly caused by an adynamic juxtavesical segment of the ureter that fails to effectively propagate

urine from the ureter into the urinary bladder.

•Secondary obstructed megaureter:

–This occurs usually when ureteral dilatation is the result of a functional ureteral obstruction associated with elevated bladder pressures secondary to PUV or a neurogenic bladder that impedes ureteral emptying.

222 |

7 Congenital Megaureter |

|

|

Classification of Megaureter

•The international classification of Smith et al. is the most comprehensive classification.

–Obstructed

–Refluxing

–Unobstructed

–None refluxing

•Each of these categories is subdivided into a primary and secondary group.

–Primary obstructed megaureter

–Secondary obstructed megaureter

–Primary refluxing megaureter

–Secondary refluxing megaureter

–Primary nonrefluxing/nonobstructing megaureter

–Secondary nonrefluxing/nonobstructing megaureter

–Primary refluxing/obstructed megaureter

•Primary refluxing megaureter:

–This is associated with severe VUR that alters the uretero-vesical junction leading to dilatation of the ureter.

–The megaureter-megacystis syndrome is an extreme form of primary refluxing megaureters.

•Secondary refluxing megaureter:

–This occurs secondary to posterior urethral valve and neurogenic bladder.

–Elevated urinary bladder pressure causes decompensation of the one-way valve at the uretero-vesical junction.

Class |

Primary |

Secondary |

Obstructed |

Intrinsic |

Infravesical |

|

ureteric |

obstruction |

|

obstruction (an |

(elevated bladder |

|

adynamic |

pressure secondary |

|

juxtavesical |

to PUV or a |

|

segment of the |

neurogenic bladder |

|

ureter) |

that impedes |

|

|

ureteral emptying) |

Refluxing |

Reflux is the |

Associated with |

|

only |

bladder outlet |

|

abnormality |

obstruction or |

|

(severe VUR |

neurogenic bladder |

|

that alters the |

(Elevated urinary |

|

uretero-vesical |

bladder pressure |

|

junction) |

causes |

|

|

decompensation of |

|

|

the uretero-vesical |

|

|

junction |

Non- |

Idiopathic |

Polyuria (diabetes |

refluxing/ |

ureteric |

insipidus) or |

unobstructed |

dilatation |

gram – ve UTI |

|

(No obstruction |

|

|

or reflux) |

|

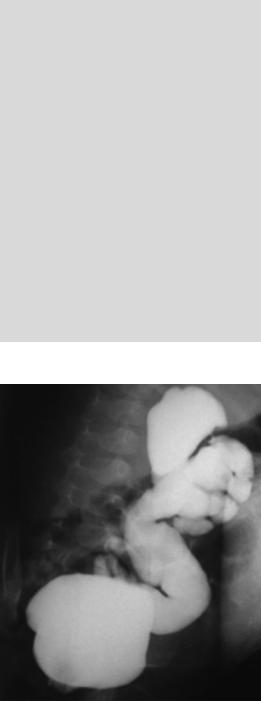

Fig. 7.11 Micturating cystourethrogram showing massively dilated ureter

•Primary nonrefluxing/nonobstructed megaureter:

–This is diagnosed when no evidence of obstruction or reflux can be demonstrated.

•Secondary nonrefluxing/nonobstructed megaureter:

–This occurs secondary to diabetes insipidus, in which high urinary flow rates may overwhelm the maximum transport