- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney |

11 |

|

|

1.3.6Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

•Numerous renal cysts are seen in the cystic kidney diseases, which include polycystic kidney disease and medullary sponge kidney.

•Simple renal cysts are different from these cysts.

•A renal cyst is an abnormal fluid collection in the kidney.

•Simple kidney cysts do not enlarge the kidneys, replace their normal structure, or cause reduced kidney function like PKD.

•Significant renal damage is rare in these cysts and usually only requires continuous followup and no surgical interventions.

•There are several types of renal cysts based on the Bosniak classification.

•The Bosniak classification categorizes renal cysts into five groups.

–Category I:

•Benign simple cyst with thin wall without septa, calcifications, or solid components.

•It does not enhance with contrast, and has a density equal to that of water.

–Category II:

•Benign cyst with a few thin septa, which may contain fine calcifications or a small segment of mildly thickened calcification.

•This includes homogenous, highattenuation lesions less than 3 cm with sharp margins but without enhancement.

•Hyperdense cysts must be exophytic with at least 75 % of its wall outside the kidney to allow for appropriate assessment of margins, otherwise they are categorized as IIF.

–Category IIF:

•Up to 5 % of these cysts are malignant and as such they require follow-up imaging, though there is no consensus recommendation on the appropriate interval of follow up.

•Well marginated cysts with a number of thin septa, with or without mild enhancement or thickening of septa.

•Calcifications may be present; these may be thick and nodular. There are no enhancing soft tissue components.

•This also includes nonenhancing highattenuation lesions that are completely

contained within the kidney and are 3 cm or larger.

–Category III:

•Indeterminate cystic masses with thickened irregular septa with enhancement.

•50 % of these lesions are ultimately found to be malignant.

–Category IV:

•Malignant cystic masses with all the characteristics of category III lesions but also with enhancing soft tissue components independent of but adjacent to the septa.

•100 % of these lesions are malignant.

•The majority are benign, simple cysts that can be monitored. However, some are cancerous or are suspicious for cancer and these are removed.

•Simple renal cysts are more common as people age. An estimated 25 % of people 40 years of age and 50 % of people 50 years of age have simple kidney cysts.

•The cause of simple kidney cysts is not fully understood and several theories were proposed.

–Obstruction of tubules

–Deficiency of blood supply to the kidneys may play a role.

–Diverticula sacs that form on the tubules, may detach and become simple kidney cysts.

•Simple kidney cysts usually do not cause symptoms or negatively affect the kidneys.

•In some cases, however, pain can develop when cysts enlarge and press on other organs.

•Most simple kidney cysts are found during imaging tests done for other reasons.

•Sometimes cysts become infected, causing fever, pain, and tenderness.

•Some studies have found a relationship between simple kidney cysts and high blood pressure.

12 |

1 Congenital Urological Malformations |

|

|

•When a cyst is found, the following imaging tests can be used to differentiate between simple and complicated renal cysts.

–Abdominal ultrasound

–CT-scan

–MRI

•Simple renal cysts that do not cause any symptoms require no treatment and can be monitored with periodic ultrasounds.

•Symptomatic simple renal cysts can be treated with ultrasound guided sclerotherapy.

•Large symptomatic simple renal cysts can be drained and deroofed laparoscopically.

•Parapelvic cysts:

–Parapelvic cysts originate from around the kidney at the adjacent renal parenchyma, and plunge into the renal sinus.

•Peripelvic cysts:

–Peripelvic cysts are contained entirely within the renal sinus, possibly related to dilated lymphatic channels.

–They can mimic hydronephrosis when viewed on CT in absence of contrast.

1.3.7Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

•Renal ectopy and fusion are common congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, and result from disruption of the normal embryologic migration of the kidneys.

•Although children with these anomalies are generally asymptomatic, some children develop symptoms due to complications, such as infection, renal calculi, and urinary obstruction (Figs. 1.13, 1.14, 1.15, 1.16, 1.17, and 1.18).

•The most frequent abnormality seen is a horseshoe kidney containing two excretory systems and two ureters.

•They are usually asymptomatic but are prone to obstruction.

1.3.8Horseshoe Kidney

•A horseshoe kidney is formed by fusion across the midline of two distinct functioning kidneys, one on each side of the midline.

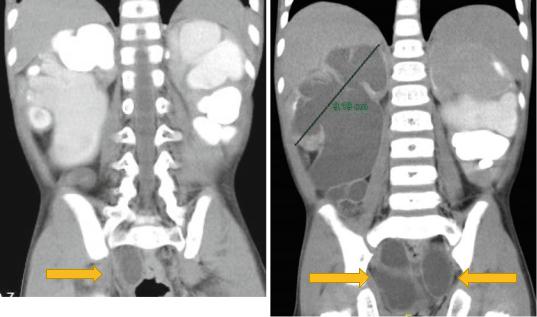

Figs. 1.13 and 1.14 CT-urography showing bilateral duplex kidney with hydroueters. Note the associated hydronephrosis and the massively dilated ureters

1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney |

13 |

|

|

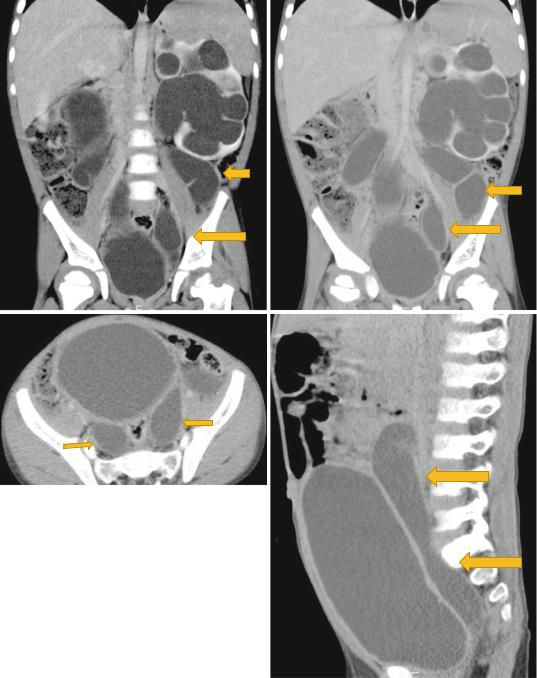

Figs. 1.15, 1.16, 1.17, and 1.18 CT-urography showing duplex kidneys with hydronephrosis and hydroureters

14 |

1 Congenital Urological Malformations |

|

|

•They are connected by an isthmus of either functioning renal parenchyma or fibrous tissue.

•In the vast majority of cases the fusion is between the lower poles (90 %).

•In the remainder the superior or both the superior or inferior poles are fused. This latter configuration is referred to as a sigmoid kidney.

–The kidneys develop in the pelvis and migrate up to their final position in the retroperitoneal space in the lumbar region.

•Prior to their ascent, the renal capsule has not matured and the kidneys still lie within the pelvis.

•It is suggested that abnormal flexion or growth of the developing spine and pelvic organs brings the immature kidneys together for a longer period than usual, leading to fusion of the two renal elements and hence forming the so-called horseshoe kidney.

•As this abnormal fusion occurs in the pelvis, the subsequent kidney cannot undergo normal migration and rotation.

•In the normal kidneys, the lower poles of the kidneys rotate laterally. However, with a horseshoe kidney, these poles remain medially positioned.

•The horseshoe kidney cannot migrate to the usual position because the fusion will not allow passage by the inferior mesenteric artery.

•Horseshoed kidney is the most common type of fusion anomaly.

•For the most part, the horseshoe kidney functions as a normal kidney. Many times, kidney malformations are accompanied by lower urinary tract anomalies as well.

•With horseshoe kidney, the kidneys can be located anywhere along the normal embryologic ascent of the kidneys.

•In 90 % of cases, the fusion of the kidneys occurs in the lower poles. In this condition, both kidneys are malrotated and their lower poles are joined.

•The collection system of a horseshoe kidney is usually deviated inwards at the lower poles because of the fusion with the isthmus.

•The ureters arise from the kidneys anterior rather than medially.

•The ureter also has a higher insertion point into the renal pelvis than that of a normal kidney.

•The blood supply to the horseshoe kidney is also different than most kidneys. There is actually several different ways that it can receive its supply. The blood supply could arise from the aorta, the iliac arteries and the inferior mesenteric artery. And it could occur as one of these, or a combination of all of them. Although in 65 % of the cases, the isthmus is supplied by single vessel from the aorta.

•It has been estimated that 22–24.8 % of patients with horseshoe kidney also have a renal vein anomaly as well. The most common of these is multiple right renal veins.

•The kidneys are joined by an isthmus which links the lower poles in 95 % of cases and the upper poles in 5 %.

•The isthmus may be fibrotic, dysplastic, or normal renal parenchyma.

•The position of the isthmus is variable.

•The isthmus lies at level of L4 just below the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) in 40 %.

•The presence of the IMA may restrict further ascent of the horseshoe during early embryogenesis.

•In another 40 % the kidneys the isthmus is located in a normal anatomical position, whilst the kidneys lie lower in the pelvis in the remaining 20 %.

•Malrotation of the kidneys is always present and is attributed to early fusion prior to normal rotation.

•The renal pelvices remain anterior, with the ureters crossing the isthmus.

•The blood supply to horseshoe kidneys is extremely variable.

–Thirty percent have a normal anatomical pattern

–The remaining 70 % are supplied by a combination of vessels entering from the aorta or the renal, mesenteric, iliac, or sacral arteries.

–The isthmus frequently has separate blood vessels that may occasionally represent the entire renal blood supply.