- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

6.6 Ureterocele |

205 |

|

|

–It is important not to confuse a dilated distal ureter that is adjacent to the bladder with a ureterocele.

–A ureterocele that is collapsed may be missed at the time of ultrasound scanning.

•Micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG):

–This is an important investigation in patients with suspected ureterocele.

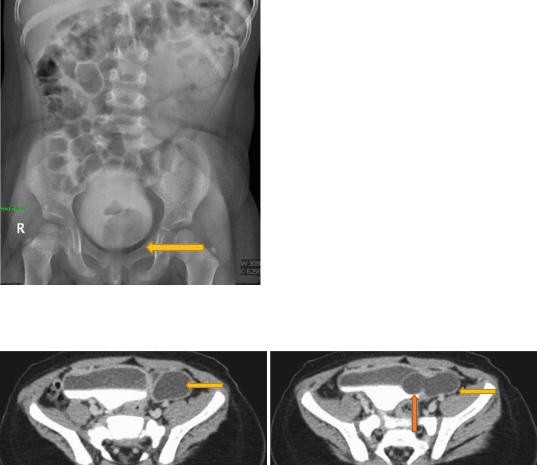

–It identifies its size, site and the relationship of the fundus and base of the ureterocele to the bladder neck and urethra, indicating possible bladder outlet obstruction (Fig. 6.27).

–MCUG is useful in detecting associated VUR.

–Care should be taken that an everted ureterocele is not miss-diagnosed as a paraureteric diverticulum.

•A Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) radionucleotide scan:

–This is useful to confirm poor function in the upper pole and also provides a baseline function prior to surgery.

•CT urography and Magnetic resonance urography (MRU):

–These can define the anatomy more clearly including the site of the ureterocele, ureter and associated renal pathology (Figs. 6.28 and 6.29).

•Cystoscopy:

–Cystoscopy is valuable to diagnose ureterocele.

–It is useful to distinguish intravesical from ectopic ureteroceles.

–When performing cystoscopy care must be taken not to obliterate the ureterocele; ideally the patient should be well hydrated, and irrigation flow kept to a minimum.

6.6.5Treatment

Fig. 6.27 A delayed film of MCUG showing a filling defect in the bladder representing a ureterocele

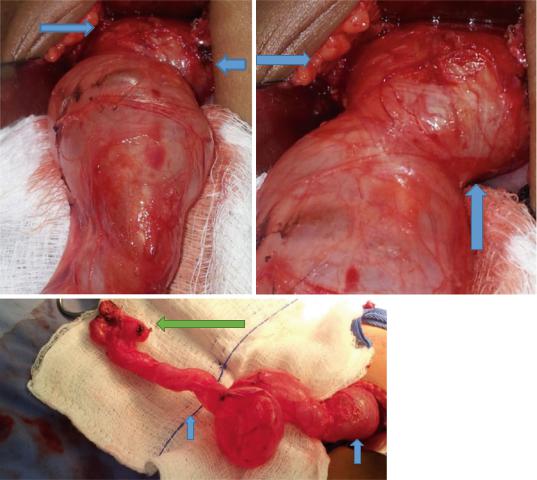

• There are several treatment options that can be offered to a patient with a ureterocele (Figs. 6.30, 6.31, and 6.32).

•The treatment options include:

–Conservative treatment

–Ureterocele puncture

–Upper pole hemi-nephrectomy

–Ureterocele excision with bladder neck repair and re-implantation

•Ureterocele puncture is appropriate for emergency decompression of acutely infected systems and for intravesical ureteroceles.

•Upper pole hemi-nephrectomy carries a good success rate where there is no associated reflux.

Figs. 6.28 and 6.29 CT urography showing ureterocele. Note the associated dilated ureter

206 |

6 Congenital Ureteral Anomalies |

|

|

Figs. 6.30, 6.31, and 6.32 Clinical intraoperative photographs showing a very large ureterocele causing obstruction. Note the associated dilated ureter and the small atrophic dysplastic kidney

•Conservative treatment:

–Expectant conservative treatment of antenatally detected ureteroceles may be successful.

–This approach avoid potentially difficult surgery and its complications.

–Leaving dysplastic renal tissue in situ may not pose an increased risk of hypertension.

–The main concern over expectant management of ureteroceles is the predisposition of an obstructed hydronephrotic kidney to infection.

•Upper pole hemi-nephrectomy:

–The upper pole of the kidney associated with a significant ureterocele usually has minimal function.

–Upper pole hemi-nephrectomy will eliminate an obstructed system predisposed to urinary tract infection and suction of the distal ureter at the time will lead to collapse and decompression of the ureterocele.

–Co-existing VUR to the lower pole is then expected to resolve in the majority of patients.

–One important advantage of heminephrectomy is that difficult surgery at the bladder neck and distal ureter is avoided.

–With this approach, re-operation is avoided in 85 % of patients.

–Bladder dysfunction seen in some of these patients is probably an inherent problem

6.6 |

Ureterocele |

|

|

207 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

associated with ureterocele and not related |

– The |

most common indication for re- |

|

|

to hemi-nephrectomy. |

|

operation is VUR. |

|

– Heminephrectomy may be complicated by |

– |

This can affect half the patients having a |

||

|

incontinence, UTI, diverticula and even |

|

ureterocele puncture and commonly affects |

|

|

bladder outlet obstruction. |

|

the upper pole in about a third. |

|

• Ureterocele puncture/endoscopic treatment: |

– |

Treatment of VUR following ureterocele |

||

– |

Endoscopic treatment of ureteroceles by |

|

puncture is reimplantation. |

|

|

puncture using cystoscopy is an alternative |

– Cystoscopic injection therapy has a success |

||

|

approach with much lower perioperative |

|

rate of 60–70 %. |

|

|

morbidity. |

• Bladder neck reconstruction: |

||

– |

It can almost be performed as day-case |

– The aim of bladder neck reconstruction is |

||

|

surgery. |

|

to correct the associated anatomical |

|

– |

Endoscopic puncture provide emergency |

|

abnormalities. |

|

|

relief of obstruction in a child presenting |

– Reconstruction may be performed as either |

||

|

with acute infection. |

|

the primary or secondary treatment. |

|

– |

Endoscopic puncture has a high success |

– |

Reconstruction surgery is difficult, espe- |

|

|

rate for intravesical ureteroceles, and for |

|

cially when performed on a young infant. |

|

|

these patients endoscopic puncture can be |

– |

In early life, ureterocele puncture may be |

|

|

offered as a definitive treatment. |

|

performed to control the risk of UTI. |

|

– This however is not the case for those with |

– Reconstruction can then be performed at an |

|||

|

ectopic ureteroceles where a high rate of |

|

older age when reconstruction surgery is |

|

|

re-operation should be expected. In these |

|

easier. |

|

|

patients, endoscopic ureterocele puncture |

– Alternatively reconstruction has been per- |

||

|

should be considered as part of a staged |

|

formed as a primary procedure with good effect. |

|

|

procedure. Endoscopic puncture in these |

– |

Reconstruction may include all or part of |

|

|

patients makes subsequent reconstructive |

|

the following: |

|

|

surgery easier, or enable VUR to be con- |

|

• Excision of the ureterocele |

|

|

trolled endoscopically. |

|

• Repairing the weakness of the bladder |

|

– |

This puncture may need to be repeated in |

|

neck and bladder wall |

|

|

10–20 % of patients. |

|

• Re-implantation of the associated ureters |

|

– |

Ureterocele puncture may be followed by |

|

• Hemi-nephrectomy of a poorly func- |

|

|

recovery of some upper pole function. |

|

tioning upper pole. |

|

– Recovery of upper pole function is likely to |

|

• Marsupialization of the ureterocele, |

||

|

be limited if underlying poor function is |

|

rather than its complete excision, may |

|

|

because of dysplasia rather than obstruction. |

|

be performed to avoid difficult dissec- |

|

– The main criticism of ureterocele puncture as |

|

tion in the urethra. |

||

|

a treatment modality is the need for further |

|

• The benefit of reconstruction is that the |

|

|

surgery, despite adequate decompression. |

|

functional problems associated with the |

|

– It was reported that about 47 % of patients |

|

ureterocele can all be corrected. These |

||

|

with ureterocele treated by endoscopic |

|

include: |

|

|

puncture required further surgery. The risk |

|

– |

VUR |

|

of reoperation increases up to 70 % with |

|

– |

Sphincter weakness |

|

extended follow-up. |

|

– |

Bladder outlet obstruction |

– The chance of re-operation is higher: |

– |

Uretero-ureterostomy: |

||

|

• When the ureterocele is ectopic com- |

|

• This is a simple technique to treat chil- |

|

|

pared to intravesical |

|

dren with ureterocele. |

|

|

• In a duplex system compared to a single |

|

• Uretero-ureterostomy has less morbid- |

|

|

system |

|

ity when compared to heminephrectomy |

|

|

• If there is pre-existing reflux |

|

and or reconstruction. |

|

208 |

6 Congenital Ureteral Anomalies |

|

|

•The procedure is based on anastomosing the upper pole ureter to the lower pole to provide effective drainage.

•Uretero-ureterostomy may be combined with ureteric re-implantation of the less dilated ureter with good outcome.

•One of the advantages of ureteroureterostomy is that it can be performed through a small incision or laparoscopically.

•Single system ureterocele:

–A fifth of all ureteroceles occur in single systems.

–Single system ureteroceles are most commonly intravesical.

–The associated kidneys often have reasonable function.

–The majority of single system ureteroceles presenting in childhood are detected antenatally.

–The treatment of single system ureterocele depends on the presence or absence of obstruction.

–Conservative treatment:

•If there is no obstruction or reflux of the affected kidney then non-surgical conservative treatment is appropriate.

–Surgical treatment:

•If the ureterocele impairs the drainage of an affected kidney then surgery is indicated.

•Transurethral endoscopic puncture or incision of the ureterocele is much more likely to be successful in simplex system ureteroceles than in duplex kidneys.

•Re-operation rates for ureteroceles in single systems are low (0–25 %).

6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

•Treatment of the ureterocele is based upon relief of obstruction.

•Endoscopic puncture may be used in cases in which urgent decompression is required (e.g. urosepsis, severe compromise in renal function), or it may be used as definitive therapy in the case of a single-system intravesical ureterocele.

•These include:

–Urosepsis

–Severe compromise in renal function.

•Endoscopic decompression in cases of ectopic ureterocele constitutes definitive treatment in only 10–40 % as there is frequently associated VUR, which often requires subsequent surgical correction.

•Options for open surgical reconstruction include ureteropyelostomy, ureteroureterostomy, excision of ureterocele and ureteral reimplantation, or upper-pole heminephrectomy with partial ureterectomy and ureterocele decompression.

•In patients with a single-system ureterocele and an associated nonfunctioning kidney, a nephroureterectomy may be performed.

•In the case of obstructive ureteroceles, treatment to relieve obstruction optimizes preservation of renal function as chronic obstruction can lead to renal deterioration.

6.7Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

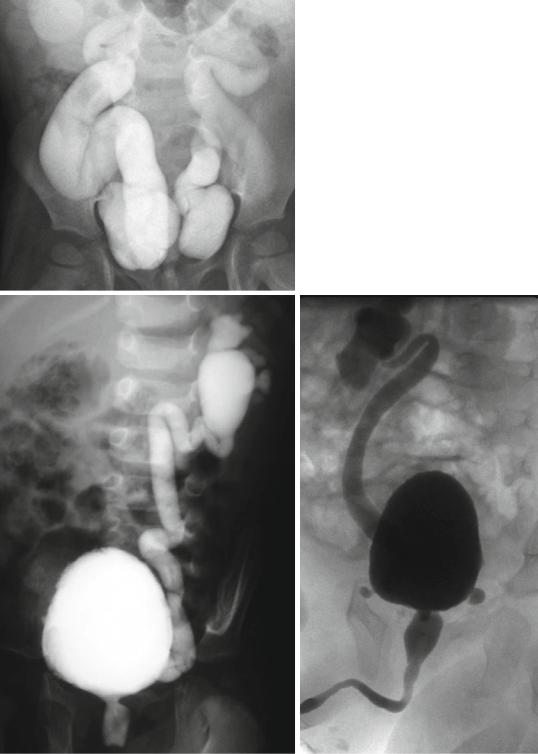

•VUR is retrograde flow of urine from the urinary bladder into the ureter and/or kidney (Figs. 6.33 and 6.34).

•One of the common complications of VUR is urinary tract infection.

•This causes reflux-induced renal injury.

•Reflux that is secondary to high bladder pressures such as those occurring in patients with posterior urethral valves (PUV) or bladder outlet obstruction is frequently associated with renal injury.

•Reflux-induced renal injury may range from clinically silent focal scars to generalized scarring and renal atrophy (reflux nephropathy).

•This may lead to:

–Hypertension (renin-mediated)

–Renal insufficiency

–End-stage renal disease

•VUR may be associated with areas of renal dysplasia or hypoplasia.

•These are seen in the absence of urinary tract infection and may be due to abnormal renal development.

6.7 Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR) |

209 |

|

|

Figs. 6.33 and 6.34 Micturating cystourethrograms showing severe bilateral reflux

•The incidence of VUR in otherwise healthy children is approximately 1 %.

•The incidence is approximately 40 % in patients undergoing evaluation for UTI.

•The reported risk of reflux in a sibling is 27–43 %.

•Approximately 50 % of the offspring of women with reflux will also have VUR.

•Normally, the distal ureter enters the urinary bladder through a submucosal tunnel.

•The submucosal tunnel length is the most important component of a competent uretrovesical junction.

•A competent uretrovesical junction provides a one way valve that allows antegrade passage of urine from the ureter into the urinary bladder.

•This one way valve prevents retrograde passage of urine from the urinary bladder into the ureter.

•Failure of this uretrovesical junction one way valve will result in VUR.

•Vesicoureteral reflux is divided into two types based on etiology.

•Primary VUR:

–This is secondary to a congenitally deficient UVJ

•Secondary VUR:

–This is secondary to several factors that affect the uretrovesical junction.

–These factors include (Figs. 6.35, 6.36, and 6.37):

•Loss of UVJ compliance during UTI

•Bladder diverticulum

•Ureterocele

•Neurovesical dysfunction or neurogenic bladder

•Bladder outlet obstruction

•Indications for surgical interventions:

–Absolute indications:

•Progressive renal injury

•Documented failure of renal growth

•Breakthrough pyelonephritis

•Intolerance or noncompliance with antibiotic suppression

•Parental preference

–Relative indications:

•Pubertal age

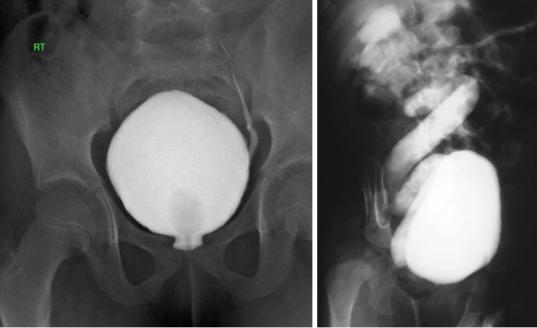

•High-grade (IV or V) VUR (Figs. 6.38 and 6.39)

•Failure to resolve

•Increasing experience shows that a considerable number of children with VUR may

210 |

6 Congenital Ureteral Anomalies |

|

|

Figs. 6.35, 6.36, and 6.37 Micturating cystourethrograms showing primary VUR and secondary VUR associated with posterior urethral valves

6.7 Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR) |

211 |

|

|

Figs. 6.38 and 6.39 Micturating cystourethrograms showing mild and severe VUR

demonstrate improved renal function on radiography, without surgical intervention.

•Nonoperative treatment mandates close fol- low-up care in patients with VUR.

•Nonoperative management of VUR includes:

–Antimicrobial suppression

–Treatment of voiding dysfunction

–Regular imaging studies to assess renal growth, renal scarring, and possible resolution of pathology.

•The need for antibiotic prophylaxis in all patients with VUR has been brought into question.

•Current recommendations include low-dose antibiotic suppression in children younger than 1 year with VUR and a history of febrile UTI, based on greater morbidity from recurrent UTI in this population.

•Use of antibiotic prophylaxis in older children with VUR should be made on an individualized basis; however, the use of prophylaxis would appear to be the most beneficial in those with grade 3 or greater reflux, girls, those with a significant history of recurrent febrile UTIs, and/ or those with bowel or bladder dysfunction.

•Surgical treatment:

–Because the submucosal ureter tends to lengthen with age, the ratio of tunnel length to ureteral diameter also increases, and the propensity for reflux may disappear.

–Successful nonoperative management of VUR requires preventing renal damage from pyelonephritis and has involved the use of continuous antibiotic prophylaxis and treating bowel or bladder dysfunction.

–Dextranomer hyaluronic acid copolymer is a bulking agent for endoscopic treatment of VUR.

–Endoscopic treatment results in reflux resolution or downgrading in most patients, with long-term success rates of approximately 60–70 %.

–Although not as effective as open ureteral reimplantation, endoscopic correction of VUR offers a minimally invasive, outpatient procedure with a low risk of complications.

–In general, ureteral reimplantation has excellent results (>95 % success rate). Although the transvesical approach is