- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

23.3 Etiology |

505 |

|

|

Figs. 23.4 and 23.5 Clinical photograph showing priapism in two children with sickle cell disease

•Factors that can contribute to priapism include the following:

–Blood disorders including:

•Sickle cell anemia

•Leukemia

–Medications including:

•Oral medications used to treat erectile dysfunction, such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis) and vardenafil (Levitra)

•Drugs injected directly into the penis to treat erectile dysfunction, such as papaverine

•Antidepressants, such as fluoxetine (Prozac) and bupropion (Wellbutrin)

•Drugs used to treat psychotic disorders, such as risperidone (Risperdal) and olanzapine (Zyprexa)

•Anticoagulant, such as warfarin (Coumadin) and heparin

•Alcohol and drug abuse (marijuana or cocaine)

–Trauma or injury to the genitals, pelvis or the perineum is a cause of nonischemic (high flow) priapism

–Other causes of priapism include:

•Spinal cord injury

•Blood clots

•Poisonous venom, such as venom from scorpions or black widow spiders

23.3Etiology

•Priapism can be idiopathic or can be secondary to a variety of diseases, conditions, or medications.

•In the United States, the most common cause of priapism in the adult population involves agents used to treat erectile dysfunction.

•Internationally, most cases are idiopathic.

•The most common cause of priapism in the pediatric population is sickle cell disease (SCD), which is responsible for more than 65 % of cases.

•Leukemia, trauma, and idiopathic causes are the causes in 10 % of patients.

•Pharmacologically induced priapism is the etiology in 5 % of children.

•Among the secondary causes of low-flow priapism are the followings:

–Sickle cell anemia – One study found that, in unscreened children with SCD, priapism was the first presentation in 0.5 % of cases.

–Thalassemia

–Dialysis

–Vasculitis

–Fat embolism (from multiple long-bone fractures or intravenous infusion of lipids as part of total parenteral nutrition)

506 |

23 Priapism in Children |

|

|

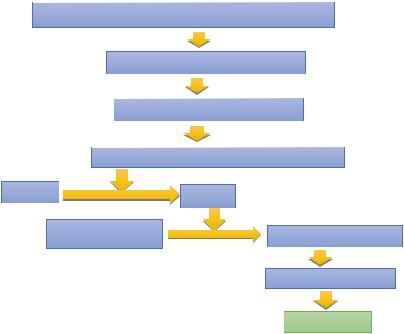

PHYSICAL OR PSYCHOLOGICAL STIMULATION

PARASYMPATHETIC SYSTEM

RELEASE OF NITRIC OXIDE

ACTIVATION OF GUANYLATE CYCLASE

GMP |

|

cGMP |

|

|

|

|

CELLULAR Ca |

EXTRCELLULAR Ca |

|

|

|

|

|

VASODILATATION |

|

|

ERECTION |

–Neurologic diseases that can result in lowflow priapism include the following:

•Spinal cord stenosis (i.e. trauma to the medulla)

•Autonomic neuropathy and cauda equina compression

–Neoplastic disease (metastatic to the penis or obstructive to venous outflow) that can result in low-flow priapism include the following:

•Prostate cancer

•Bladder cancer (highest risk)

•Hematologic cancer (leukemia)

•Renal carcinoma

•Melanoma

–Pharmacologic causes of low-flow priapism include the following:

•Intracavernosal agents – Papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin E1

•Intraurethral pellets (i.e. medicated urethral system for erection with intracavernosal prostaglandin E1)

•Antihypertensives – Ganglion-blocking agents (e.g. guanethidine), arterial vasodilators (e.g. hydralazine), alpha-antagonists (e.g. prazosin), calcium channel blockers

•Psychotropics – Phenothiazine, butyrophenones (e.g. haloperidol), perphenazine, trazodone, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram) [3]

•Anticoagulants – Heparin, warfarin (during rebound hypercoagulable states)

•Recreational drugs – Cocaine

•Hormones – Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), tamoxifen, testosterone, androstenedione for athletic performance enhancement

•Herbal medicine – Ginkgo biloba with concurrent use of antipsychotic agents

•Miscellaneousagents–Metoclopramide, omeprazole, penile injection of cocaine, epidural infusion of morphine and bupivacaine

•Only rare case reports have associated phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors such as sildenafil with priapism. In fact, several reports suggest sildenafil as a means to treat priapism and as a possible means of preventing full-blown episodes in patients with sickle cell disease.

23.4 |

Classification of Priapism |

|

507 |

|||

|

|

|

||||

• High-flow priapism may result from the fol- |

|

corpora cavernosa while the venous |

||||

lowing forms of genitourinary trauma: |

|

drainage remains normal. |

||||

– |

Straddle injury |

|

|

|

|

• An adequate arterial flow and well- |

– Intracavernous injections resulting in direct |

|

oxygenated corpora |

||||

|

cavernosal artery injury |

|

• The prognosis is better, and secondary |

|||

• Rare causes of priapism include the |

|

impotence is rare (<20 %). |

||||

following: |

|

|

|

|

• In children high flow priapism is typi- |

|

– Amyloidosis (massive amyloid infiltration) |

|

cally caused by post-traumatic arterio- |

||||

– Gout (one case report) |

|

cavernosal fistula (from penile, perineal |

||||

– |

Carbon monoxide poisoning |

|

or pelvic trauma), and generally mani- |

|||

– |

Malaria |

|

|

|

|

fests several days after the trauma. |

– Black widow spider bites |

|

• Evidence of blunt or penetrating injury |

||||

– |

Asplenia |

|

|

|

|

to the penis or perineum especially |

– |

Fabry disease (rare association, occasion- |

|

straddle injury is usually the initiating |

|||

|

ally noted to be priapism of the high-flow |

|

event. |

|||

|

type) |

|

|

|

|

• It can also be caused by: |

– |

Vigorous sexual activity |

|

– Intracavernosal injections of vasoac- |

|||

– Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (mech- |

|

tive agents |

||||

|

anism is thought to be a hypercoagulable |

|

– Scorpion or snake bites |

|||

|

state induced by the infection) |

|

– Substance abuse (mainly cocaine, |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

which can cause high or low output |

|

|

|

|

|

|

priapism) |

23.4 |

Classification of Priapism |

|

||||

|

– Therapeutic drugs (especially psy- |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

chiatric medications with autonomic |

• Priapism is a sustained painful erection of the |

|

nervous system effects |

||||

penis often nocturnal or starting in the early |

|

– Infectious diseases or tumors |

||||

hours of the morning. |

|

|

• Low flow priapism (ischemic): |

|||

• Priapism develops when there is excess arte- |

– This is the commonest type |

|||||

rial inflow to the penis or when there is persis- |

– Low flow priapism is characterized by loss |

|||||

tent venous outflow obstruction to the penis. |

|

of vascular regulation. |

||||

• Priapism is classified into two main types: |

– |

Venous drainage is impaired, presumably |

||||

– |

High flow arterial priapism. This is also |

|

as a consequence of vascular blockage by |

|||

|

called non-ischemic priapism. |

|

deformed red blood cells. |

|||

– Low flow priapism. This is also called isch- |

– This is the classic type seen in patients with |

|||||

|

emic priapism. |

|

|

|

|

SCD where there is stasis leading to |

• High flow (non-ischemic) priapism: |

|

hypoxia and acidosis of venous blood in a |

||||

– This is usually seen following trauma caus- |

|

normally erected penis. This will lead to |

||||

|

ing injury to the cavernosal artery. |

|

sickling of RBCs within the corpora caver- |

|||

– This type of priapism is generally not pain- |

|

nosa venous sinusoids, venous outflow |

||||

|

ful and may manifest in an episodic |

|

obstruction and engorgement of the cor- |

|||

|

manner. |

|

|

|

|

pora cavernosa. The corpora spongiosa and |

– |

The penis in high flow priapism is neither |

|

glans of the penis are spared. |

|||

|

fully rigid nor painful and does not require |

– |

The corpora cavernosa becomes rigid and |

|||

|

an emergency treatment. |

|

tender to palpation. |

|||

– |

Characteristics |

of |

high-flow priapism |

– |

This may be further complicated as the |

|

|

include the following: |

|

fixed resistance maintained by the adventi- |

|||

|

• High flow priapism is characterized by |

|

tia of the corpora cavernosa causes a com- |

|||

|

an increase |

of |

arterial supply to the |

|

partment syndrome. |

|

508 |

23 Priapism in Children |

|

|

–Low-flow priapism is generally painful, although the pain may disappear with prolonged priapism.

–Characteristic features of low-flow priapism include the following:

•Rigid erection

•Ischemic corpora as indicated by dark blood upon corporeal aspiration

•No evidence of trauma

–Low flow priapism is considered a medical and surgical emergency and priapism should be resolved within 6 h of the onset of the episode to minimize the sequelae.

–In addition to SCD, low flow priapism can be caused other hematologic diseases with hypercoagulability or hyperviscosity such as leukemia’s and several drugs.

•It is important to differentiate between these two types as the management and prognosis are different.

•The two types of priapism can be differentiated using color duplex Doppler ultrasonography and analysis of blood aspirated from the corpora cavernosa.

–Color Doppler ultrasonography measures blood flow. This typically show little or no blood flow in the cavernosal arteries in those with low flow priapism.

–Analysis of blood aspirated from the corpora cavernosa is done at the time of aspiration and irrigation.

–In patients with high flow priapism, the aspirated blood:

•Is bright red

• Has a pO2 >90 % mmHg, pCO2 <40 mmHg and a pH of approximately 7.40.

–In patients with low flow priapism, the aspirated blood:

•Is dark in color

•Has a pO2 <30 mmHg, pCO2 >60 mmHg and a pH <7.25.

•Priapism is also classified into two types:

–Stuttering priapism: This lasts 2–4 h, often recurrent and may precede a severe attack.

–Acute (Severe) priapism: This lasts longer than 4 h and can result in impotence.

23.5Clinical Features

•Priapism causes abnormally persistent erections not related to sexual stimulation.

•Priapism symptoms may vary depending on the type of priapism.

•There are two main types of priapism: ischemic and nonischemic priapism.

•Ischemic priapism:

–Ischemic, also called low-flow, priapism is the result of blood stasis in the penis.

–It’s the more common type of priapism.

–Low-flow, ischemic-type priapism is generally painful, although the pain may disappear with prolonged priapism.

–It is characterized by ischemic corpora, as indicated by dark blood upon corporeal aspiration; and no evidence of trauma

–The history may reveal an underlying cause

–Stuttering priapism is unwanted erection off and on for several hours.

–Signs and symptoms include:

•Unwanted erection lasting more than 4 h

•It is characterized by a rigid, painful erection

•Rigid penile shaft, but usually soft glans of penis

•Usually painful or tender penis

•Nonischemic priapism:

–Nonischemic, or high-flow, priapism occurs when too much blood flows into the penis.

–This type of priapism is associated with blunt or penetrating injury to the perineum. It may manifest in an episodic manner.

–Nonischemic priapism is usually painless.

–Signs and symptoms include:

•Unwanted erection lasting at least 4 h

•Erect but not rigid penile shaft

•Patients with high-flow priapism typically have a history of blunt or penetrating trauma to the penis or perineum, resulting in a fistula between a cavernosal artery and the corpus cavernosum.

•Clinically, high-flow priapism is characterized by a painless erection; tumescence is typically less marked than in low-flow priapism.