- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Normal Embryology

- •1.3 Abnormalities of the Kidney

- •1.3.1 Renal Agenesis

- •1.3.2 Renal Hypoplasia

- •1.3.3 Supernumerary Kidneys

- •1.3.5 Polycystic Kidney Disease

- •1.3.6 Simple (Solitary) Renal Cyst

- •1.3.7 Renal Fusion and Renal Ectopia

- •1.3.8 Horseshoe Kidney

- •1.3.9 Crossed Fused Renal Ectopia

- •1.4 Abnormalities of the Ureter

- •1.5 Abnormalities of the Bladder

- •1.6 Abnormalities of the Penis and Urethra in Males

- •1.7 Abnormalities of Female External Genitalia

- •Further Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Pathophysiology

- •2.3 Etiology of Hydronephrosis

- •2.5 Clinical Features

- •2.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •2.7 Treatment

- •2.8 Antenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Further Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Embryology

- •3.3 Pathophysiology

- •3.4 Etiology of PUJ Obstruction

- •3.5 Clinical Features

- •3.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •3.7 Management of Newborns with PUJ Obstruction

- •3.8 Treatment

- •3.9 Post-operative Complications and Follow-Up

- •Further Reading

- •4: Renal Tumors in Children

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.2 Etiology

- •4.2.3 Histopathology

- •4.2.4 Nephroblastomatosis

- •4.2.5 Clinical Features

- •4.2.6 Risk Factors for Wilms’ Tumor

- •4.2.7 Staging of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.8 Investigations

- •4.2.9 Prognosis and Complications of Wilms Tumor

- •4.2.10 Surgical Considerations

- •4.2.11 Surgical Complications

- •4.2.12 Prognosis and Outcome

- •4.2.13 Extrarenal Wilms’ Tumors

- •4.3 Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.3 Epidemiology

- •4.3.5 Clinical Features

- •4.3.6 Investigations

- •4.3.7 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.4 Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney (CCSK)

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Pathophysiology

- •4.4.3 Clinical Features

- •4.4.4 Investigations

- •4.4.5 Histopathology

- •4.4.6 Treatment

- •4.4.7 Prognosis

- •4.5 Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor of the Kidney

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •4.5.3 Histologic Findings

- •4.5.4 Clinical Features

- •4.5.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •4.5.6 Treatment and Outcome

- •4.5.7 Mortality/Morbidity

- •4.6 Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •4.6.1 Introduction

- •4.6.2 Histopathology

- •4.6.4 Staging

- •4.6.5 Clinical Features

- •4.6.6 Investigations

- •4.6.7 Management

- •4.6.8 Prognosis

- •4.7 Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •4.7.1 Introduction

- •4.7.2 Histopathology

- •4.7.4 Clinical Features

- •4.7.5 Investigations

- •4.7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.8 Renal Lymphoma

- •4.8.1 Introduction

- •4.8.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •4.8.3 Diagnosis

- •4.8.4 Clinical Features

- •4.8.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •4.9 Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •4.10 Metanephric Adenoma

- •4.10.1 Introduction

- •4.10.2 Histopathology

- •4.10.3 Diagnosis

- •4.10.4 Clinical Features

- •4.10.5 Treatment

- •4.11 Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •Further Reading

- •Wilms’ Tumor

- •Mesoblastic Nephroma

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma in Children

- •Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney

- •Renal Lymphoma

- •Ossifying Renal Tumor of Infancy

- •Metanephric Adenoma

- •Multilocular Cystic Renal Tumor

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Embryology

- •5.4 Histologic Findings

- •5.7 Associated Anomalies

- •5.8 Clinical Features

- •5.9 Investigations

- •5.10 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •6: Congenital Ureteral Anomalies

- •6.1 Etiology

- •6.2 Clinical Features

- •6.3 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.4 Duplex (Duplicated) System

- •6.4.1 Introduction

- •6.4.3 Clinical Features

- •6.4.4 Investigations

- •6.4.5 Treatment and Prognosis

- •6.5 Ectopic Ureter

- •6.5.1 Introduction

- •6.5.3 Clinical Features

- •6.5.4 Diagnosis

- •6.5.5 Surgical Treatment

- •6.6 Ureterocele

- •6.6.1 Introduction

- •6.6.3 Clinical Features

- •6.6.4 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •6.6.5 Treatment

- •6.6.5.1 Surgical Interventions

- •6.8 Mega Ureter

- •Further Reading

- •7: Congenital Megaureter

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.3 Etiology and Pathophysiology

- •7.4 Clinical Presentation

- •7.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •7.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •7.7 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Pathophysiology

- •8.4 Etiology of VUR

- •8.5 Clinical Features

- •8.6 Investigations

- •8.7 Management

- •8.7.1 Medical Treatment of VUR

- •8.7.2 Antibiotics Used for Prophylaxis

- •8.7.3 Anticholinergics

- •8.7.4 Surveillance

- •8.8 Surgical Therapy of VUR

- •8.8.1 Indications for Surgical Interventions

- •8.8.2 Indications for Surgical Interventions Based on Age at Diagnosis and the Presence or Absence of Renal Lesions

- •8.8.3 Endoscopic Injection

- •8.8.4 Surgical Management

- •8.9 Mortality/Morbidity

- •Further Reading

- •9: Pediatric Urolithiasis

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Etiology

- •9.4 Clinical Features

- •9.5 Investigations

- •9.6 Complications of Urolithiasis

- •9.7 Management

- •Further Reading

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Embryology of Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

- •10.3 Etiology and Inheritance of PMDS

- •10.5 Clinical Features

- •10.6 Treatment

- •10.7 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Physiology and Bladder Function

- •11.2.1 Micturition

- •11.3 Pathophysiological Changes of NBSD

- •11.4 Etiology and Clinical Features

- •11.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •11.7 Management

- •11.8 Clean Intermittent Catheterization

- •11.9 Anticholinergics

- •11.10 Botulinum Toxin Type A

- •11.11 Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs

- •11.12 Surgical Management

- •Further Reading

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Etiology

- •12.3 Pathophysiology

- •12.4 Clinical Features

- •12.5 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •12.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Embryology

- •13.3 Epispadias

- •13.3.1 Introduction

- •13.3.2 Etiology

- •13.3.4 Treatment

- •13.3.6 Female Epispadias

- •13.3.7 Surgical Repair of Female Epispadias

- •13.3.8 Prognosis

- •13.4 Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.1 Introduction

- •13.4.2 Associated Anomalies

- •13.4.3 Principles of Surgical Management of Bladder Exstrophy

- •13.4.4 Evaluation and Management

- •13.5 Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.1 Introduction

- •13.5.2 Skeletal Changes in Cloacal Exstrophy

- •13.5.3 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •13.5.4 Prenatal Diagnosis

- •13.5.5 Associated Anomalies

- •13.5.8 Surgical Reconstruction

- •13.5.9 Management of Urinary Incontinence

- •13.5.10 Prognosis

- •13.5.11 Complications

- •Further Reading

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Etiology

- •14.3 Clinical Features

- •14.4 Associated Anomalies

- •14.5 Diagnosis

- •14.6 Treatment and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •15: Cloacal Anomalies

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Associated Anomalies

- •15.4 Clinical Features

- •15.5 Investigations

- •Further Reading

- •16: Urachal Remnants

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Embryology

- •16.4 Clinical Features

- •16.5 Tumors and Urachal Remnants

- •16.6 Management

- •Further Reading

- •17: Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Inguinal Hernia

- •17.2.1 Incidence

- •17.2.2 Etiology

- •17.2.3 Clinical Features

- •17.2.4 Variants of Hernia

- •17.2.6 Treatment

- •17.2.7 Complications of Inguinal Herniotomy

- •17.3 Hydrocele

- •17.3.1 Embryology

- •17.3.3 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •18: Cloacal Exstrophy

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

- •18.3 Associated Anomalies

- •18.4 Clinical Features and Management

- •Further Reading

- •19: Posterior Urethral Valve

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Embryology

- •19.3 Pathophysiology

- •19.5 Clinical Features

- •19.6 Investigations and Diagnosis

- •19.7 Management

- •19.8 Medications Used in Patients with PUV

- •19.10 Long-Term Outcomes

- •19.10.3 Bladder Dysfunction

- •19.10.4 Renal Transplantation

- •19.10.5 Fertility

- •Further Reading

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Embryology

- •20.4 Clinical Features

- •20.5 Investigations

- •20.6 Treatment

- •20.7 The Müllerian Duct Cyst

- •Further Reading

- •21: Hypospadias

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Effects of Hypospadias

- •21.3 Embryology

- •21.4 Etiology of Hypospadias

- •21.5 Associated Anomalies

- •21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias

- •21.8 Treatment

- •21.9 Urinary Diversion

- •21.10 Postoperative Complications

- •Further Reading

- •22: Male Circumcision

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •22.3 History of Circumcision

- •22.4 Pain Management

- •22.5 Indications for Circumcision

- •22.6 Contraindications to Circumcision

- •22.7 Surgical Procedure

- •22.8 Complications of Circumcision

- •Further Reading

- •23: Priapism in Children

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Pathophysiology

- •23.3 Etiology

- •23.5 Clinical Features

- •23.6 Investigations

- •23.7 Management

- •23.8 Prognosis

- •23.9 Priapism and Sickle Cell Disease

- •23.9.1 Introduction

- •23.9.2 Epidemiology

- •23.9.4 Pathophysiology

- •23.9.5 Clinical Features

- •23.9.6 Treatment

- •23.9.7 Prevention of Stuttering Priapism

- •23.9.8 Complications of Priapism and Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Embryology and Normal Testicular Development and Descent

- •24.4 Causes of Undescended Testes and Risk Factors

- •24.5 Histopathology

- •24.7 Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •24.8 Treatment

- •24.8.1 Success of Surgical Treatment

- •24.9 Complications of Orchidopexy

- •24.10 Infertility and Undescended Testes

- •24.11 Undescended Testes and the Risk of Cancer

- •Further Reading

- •25: Varicocele

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Etiology

- •25.3 Pathophysiology

- •25.4 Grading of Varicoceles

- •25.5 Clinical Features

- •25.6 Diagnosis

- •25.7 Treatment

- •25.8 Postoperative Complications

- •25.9 Prognosis

- •Further Reading

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Etiology and Risk Factors

- •26.3 Diagnosis

- •26.4 Intermittent Testicular Torsion

- •26.6 Effects of Testicular Torsion

- •26.7 Clinical Features

- •26.8 Treatment

- •26.9.1 Introduction

- •26.9.2 Etiology of Extravaginal Torsion

- •26.9.3 Clinical Features

- •26.9.4 Treatment

- •26.10 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •26.10.1 Introduction

- •26.10.2 Embryology

- •26.10.3 Clinical Features

- •26.10.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •27: Testicular Tumors in Children

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.4 Etiology of Testicular Tumors

- •27.5 Clinical Features

- •27.6 Staging

- •27.6.1 Regional Lymph Node Staging

- •27.7 Investigations

- •27.8 Treatment

- •27.9 Yolk Sac Tumor

- •27.10 Teratoma

- •27.11 Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

- •27.12 Stromal Tumors

- •27.13 Simple Testicular Cyst

- •27.14 Epidermoid Cysts

- •27.15 Testicular Microlithiasis (TM)

- •27.16 Gonadoblastoma

- •27.17 Cystic Dysplasia of the Testes

- •27.18 Leukemia and Lymphoma

- •27.19 Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma

- •27.20 Prognosis and Outcome

- •Further Reading

- •28: Splenogonadal Fusion

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Etiology

- •28.4 Associated Anomalies

- •28.5 Clinical Features

- •28.6 Investigations

- •28.7 Treatment

- •Further Reading

- •29: Acute Scrotum

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.1 Introduction

- •29.2.3 Etiology

- •29.2.4 Clinical Features

- •29.2.5 Effects of Torsion of Testes

- •29.2.6 Investigations

- •29.2.7 Treatment

- •29.3 Torsion of the Testicular or Epididymal Appendage

- •29.3.1 Introduction

- •29.3.2 Embryology

- •29.3.3 Clinical Features

- •29.3.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.4.1 Introduction

- •29.4.2 Etiology

- •29.4.3 Clinical Features

- •29.4.4 Investigations and Treatment

- •29.5 Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

- •29.6 Testicular Trauma

- •29.7 Other Causes of Acute Scrotum

- •29.8 Splenogonadal Fusion

- •Further Reading

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Imperforate Hymen

- •30.3 Vaginal Atresia

- •30.5 Associated Anomalies

- •30.6 Embryology

- •30.7 Clinical Features

- •30.8 Investigations

- •30.9 Management

- •Further Reading

- •31: Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.1 Introduction

- •31.2 Embryology

- •31.3 Sexual and Gonadal Differentiation

- •31.5 Evaluation of a Newborn with DSD

- •31.6 Diagnosis and Investigations

- •31.7 Management of Patients with DSD

- •31.8 Surgical Corrections of DSD

- •31.9 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

- •31.10 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (Testicular Feminization Syndrome)

- •31.13 Gonadal Dysgenesis

- •31.15 Ovotestis Disorders of Sexual Development

- •31.16 Other Rare Disorders of Sexual Development

- •Further Reading

- •Index

462 |

21 Hypospadias |

|

|

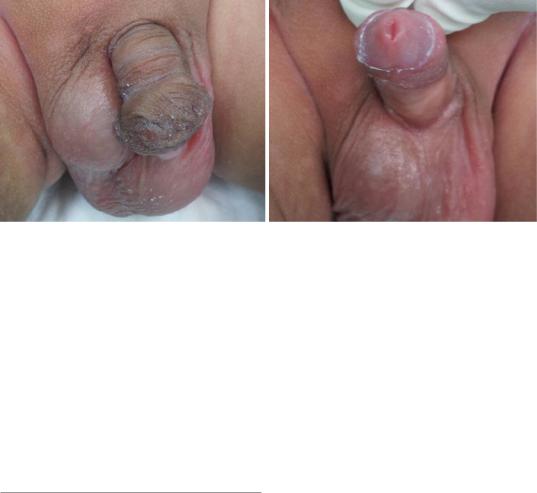

Figs. 21.31 and 21.32 Clinical photographs showing perineal hypospadias

21.7Clinical Features of Hypospadias

•The urethral opening is ectopically located on the ventral aspect of the penis proximal to the

tip of the glans penis (Figs. 21.33, 21.34, and 21.35).

•The urethral opening may be located as far down as in the scrotum or perineum.

•There is usually an associated glanular groove.

Figs. 21.33 and 21.34 Clinical photographs showing hypopsadias. Note the abnormal ectopic meatus on the ventral surface of the peis. Note also the glanular groove

21.7 Clinical Features of Hypospadias |

463 |

|

|

The depth of this groove is variable.

•A dorsal hood of foreskin is present and the prepuce is incomplete ventrally (“hooded” foreskin).

•Rarely, the foreskin may be complete, and the hypospadias is revealed at the time of circumcision. This is called the mega meatus intact

prepuce (MIP) variant of hypospadias (Figs. 21.36 and 21.37).

•The penis may have associated ventral shortening and curvature (chordee). This may be apparent during erection only and it is more commonly seen in patients with more proximal hypospadias (Figs. 21.38 and 21.39).

Fig. 21.35 A clinical photograph showing hypospadias. Note the deep glandular groove and the ectopic meatus on the ventral aspect of the penis

Figs. 21.36 and 21.37 Clinical photographs showing megameatus. Note the normal looking prepuce and also note the wide meatus

Figs. 21.38 and 21.39 Clinical photographs showing severe chordee associated with hypospadias

464 |

21 Hypospadias |

|

|

Figs. 21.40 and 21.41 Clinical photographs showing abnormal prepuce that is deficient ventrally but a normal looking meatus both in size and position

•Proximal hypospadias is commonly associated with a bifid scrotum and penoscrotal transposition.

•There may be an associated undescended testes which can be unilateral or bilateral.

•On rare occsions, the foreskin may appear abnormal resembling hypospadias but the meatus appears normal in position and site (Figs. 21.40 and 21.41).

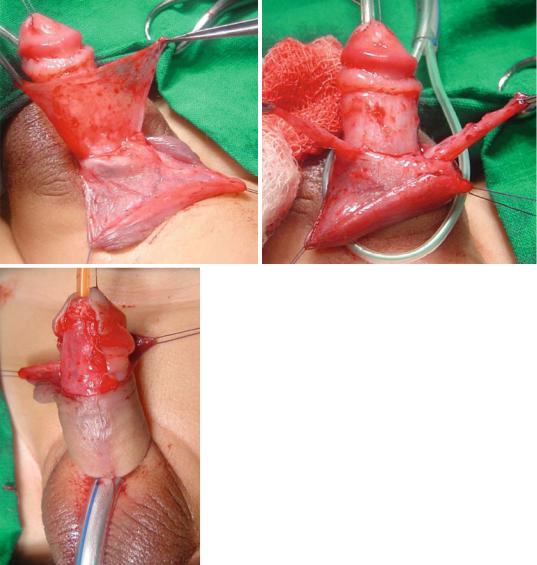

21.8Treatment

•It is important to avoid circumscion in these children as the preputial skin is often used for grafting during hypospadias repair. The dartos flap of the preputial skin is dissected and used to protect the repair either as a single or double layers. This was shown to decrease the rate of postoperative fistula formation. The preputial skin is sometimes used to cover the deficient skin ventrally as Byer’s flaps (Figs. 21.42, 21.43, and 21.44).

•Currently, most cases of hypospadias are repaired in the first 18 months of life and in a single stage (usually between 6 and 18 months of age.

•Hypospadias and hypospadias repair is known to be associated with significant psychological

effect and to decrease this effect, repair of hypospadias is currently done at an earlier age group (6–18 months). This is known to have an improved emotional and psychological result.

•Repair of mild degrees of hypospadias is mainly for cosmetic reasons as they have little effect on function except for the direction of the urinary stream.

•The aim from the surgical repair is to have a penis that has an acceptable appearance, enable the patient to void normally and suitable for sexual intercourse in the future

•Hormonal therapy (Figs. 21.45, 21.46, and 21.47):

–Hormonal therapy has been used as an adjuvant for infants with small phallic size.

–The aim is to increase the length and width of the penis.

–Testosterone injections or creams can be used.

•The recommended testosterone injection dose (long acting testosterone) is about 2 mg/ kg/dose. This is given once every 3 weeks and can be repeated to a maximum of three doses.

•Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) injections, have been used also to promote penile growth.

21.8 Treatment |

465 |

|

|

Figs. 21.42, 21.43, and 21.44 Clinical intraoperative photographs showing the use of Dartos flaps as a single or double to protect the hypospadias repair

•The treatment of hypospadias is surgical repair, not only for functional reasons but also for cosmetic reasons.

•Hypospadias repair is generally performed as a single-stage procedure.

•A staged hypospadias repair is preferable in those with excessive chordee, and a small phallic size.

•The chordee is repaired during the first stage, and the urethroplasty and glansplasty are repaired after the first stage has completely healed.

•Hypospadias repair is done under general anesthesia, most often supplemented by a nerve block to the penis or a caudal block in order to reduce the general anesthesia needed,

466 |

21 Hypospadias |

|

|

Figs. 21.45, 21.46, and 21.47 Clinical photographs show in hypospadias before and after long acting testesterone injection. Note the increase in both the length and

width of the penis. Note also the appearance of pubic hair as a side effect of long acting testesterone

and to minimize discomfort and pain after surgery.

•The goals of surgical treatment of hypospadias are as follows (Figs. 21.48 and 21.49):

–To create a straight penis by repairing any curvature (orthoplasty)

–To create a urethra with its meatus at the tip of the penis (urethroplasty)

–To re-form the glans into a more natural conical configuration (glansplasty)

–To achieve cosmetically acceptable penile skin coverage

–To create a normal-appearing scrotum

•There are those who will not repair minor cases of hypospadias, in which the meatus is located near the tip of the glans.

•Hypospadias and hypospadias repair is known to be associated with significant psychological effect and to decrease this effect, repair of hypospadias is currently done at an earlier age group (6–18 months).

•This is known to have an improved emotional and psychological result.

•There are several surgical techniques to repair hypospadias depending on the site of urethral

21.8 Treatment |

467 |

|

|

Figs. 21.48 and 21.49 Clinical photographs showing posthypospadias repair

meatus and the presence or absence of chordee.

•Any degree of chordee should be corrected prior to urethroplasty.

•This may necessitates transection of the urethral plate in severe cases, precluding its use for urethroplasty (Figs. 21.50 and 21.51).

•Residual chordee is a known case of failure of urethroplasty. Add to this the bad cosmetic appearance.

•Glanular hypospadias:

–This is commonly repaired using:

•The MAGPI (Meatal Advancement Glanduloplasty Incorporated) procedure.

•The DYG (The Double Y Glanuloplasty) procedure.

•Others continue to use perimeatal-based flaps for urethroplasty (“flip-flap repair”).

–Very mild degree of glanular hypospadias can be repaired with meatoplasty.

–There are those who advocate leaving a very mild degree of hypospadias without repair.

•Middle hypospadias:

–There are several techniques to repair this type of hypospadias.

–The TIP or Snodgrass urethroplasty (The tubularized incised plate urethroplasty) (Figs. 21.52, 21.53, 21.54, 21.55, 21.56, 21.57, 21.58, and 21.59):

•This is the commonest procedure used to repair anterior hypospadias (coronal, subcoronal, distal penile and midshaft hypospadias).

•A midline incision into the urethral plate widen it sufficiently for urethroplasty without stricture formation.

•This is suitable for cases without chordee or mild degrees of chordee.

468 |

21 Hypospadias |

|

|

Figs. 21.50 and 21.51 Clinical photographs showing proxial hypospadias with severe chordee. Note the penile length after release of chordee and how straight it became

–The Mathieu Technique:

•This was modified and called The Slit-like adjusted Mathieu (SLAM) Technique.

•The meatal-based flap technique of Mathieu was the most popular technique for distal hypospadias repair.

•This technique is not commonly used now.

•It is also not suitable for cases with chordee.

•The major drawback of the original Mathieu technique is the final appearance of the meatus (a smiling meatus that is not very terminal).

–The LABO technique (Lateral Based Onlay Flap):

•The principle of this technique is to use the lateral penile skin as well as part of the prepuce to reconstruct the new urethra.

–Lateral Based Flap:

•The lateral based flap may be used in all types of proximal hypospadias.

•This flap combines the advantages of meatal-based flap, and preputial pedicle flap techniques into one procedure without the need for an intervening anastomosis.

•It is suitable for cases with chordee as it allows for extensive excision of ventral chordee and the urethral plate without damaging the flap.

–Transverse Preputial Island Flap

–Onlay Island Flap: The Onlay Island Flap is ideal for patients with proximal hypospadias without deep Chordee

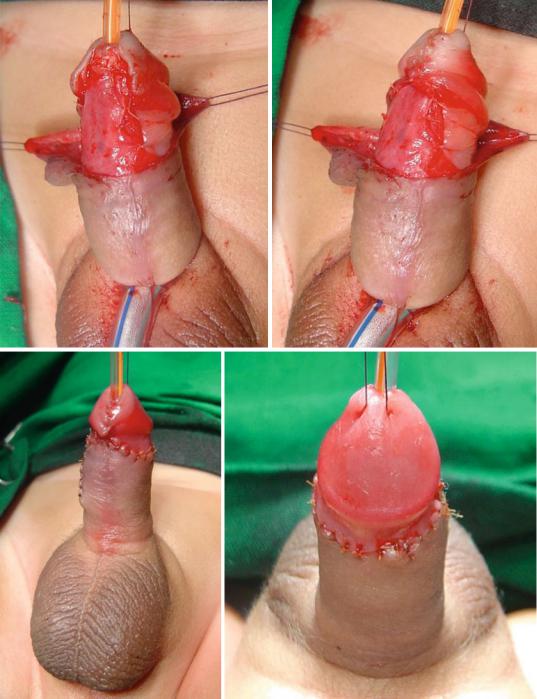

•Posterior hypospadias (Figs. 21.60, 21.61, 21.62, 21.63, 21.64, and 21.65):

–There is less consensus regarding proximal hypospadias repair.

–Most of these cases are repaired using a two Stage repair.

–These as well as a small group of patients with severe proximal hypospadias, chordee, and a small phallus.

–Patients with recurrent hypospadias and fibrous unhealthy skin may benefit from a two-stage procedure.

–In the first stage, the chordee is excised completely and this confirmed by the use of the artificial erection test.

•The second stage of the procedure is carried out 6–12 months later.

•The tubularized incised plate (TIP) repair has become the most commonly used repair for both distal and midshaft hypospadias. This procedure can be used for all distal hypospa-

21.8 Treatment |

469 |

|

|

Figs. 21.52, 21.53, 21.54, 21.55, 21.56, 21.57, 21.58, and 21.59 Clinical photographs showing the steps of TIP procedure. The repair was reinforced with a double layer of dartos flaps

470 |

21 Hypospadias |

|

|

Figs. 21.52, 21.53, 21.54, 21.55, 21.56, 21.57, 21.58, and 21.59 (continued)

21.8 Treatment |

471 |

|

|

Figs. 21.60, 21.61, and 21.62 Clinical photograph showing the second stage repair of proximal hypospadias after release of chordee. The ventral skin defect was covered with a Byer’s flaps

Figs. 21.63, 21.64, and 21.65 Clinical photographs showing proximal hypospadias without chordee that was repaired using TIP technique