- •English for Professional Purposes: Business

- •Санкт-Петербург

- •Contents

- •Getting to know your colleagues

- •In what situations would you use the words and expressions below?

- •Farm project

- •Rain forest project

- •Peace project

- •Ben & Jerry’s Projects

- •Interpreting information

- •Reviewing background information and vocabulary

- •Introductory notes

- •Language hints for negotiation: conceding a point

- •Situation

- •2. Notice the format of the meeting.

- •3. Review your notes on Ben & Jerry’s Projects, the vocabulary, the information on business culture, and the negotiating strategy. Prepare to use this information in the meeting.

- •Verb Salad ben & jerry’s homemade, inc.

- •Part II

- •By Roger Ebert

- •Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron)

- •Vocabulary

- •Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room

- •Part III

- •Introducing the topic. Discuss these questions with another student, then with the class.

- •Main Ideas and Details

- •Vocabulary

- •Sports idioms in business

- •It's a whole new ballgame.

- •Vocabulary exercise

- •Drop, fall, fall sharply, inch down, surge in, decline, level off, plummet, plunge, rise, gain, stagnate, go nowhere, soar

- •Famous quotes from the world of business sentence stress practice

- •Discuss the meaning of the sentences

- •Now mark these yourself and say them aloud.

- •Part IV

- •Vocabulary from the Reading

- •The Star in Starbucks

- •Fielding Questions Some handy phrases for dealing with questions

- •Helpful advice Effective Visual Aids

- •Persuasive speaking for business assignment #1 topics for presentation

- •Article sources:

- •Persuasive Speaking for Business Assignment #2

- •Persuasive Speaking for Business Assignment # 3 (practicing presentation skills in a persuasive presentation, team working)

- •Ideas for Products and Services

- •IPhone competitor

- •Part V executive compensation at general electric

- •Part VI

- •Vocabulary in Context. Find a synonym for the underlined words in each of these sentences.

- •Part VII

- •Vocabulary in Context

- •Talking about brands the purest treasure

- •Reviewing background information and vocabulary

- •Glossary

- •Oxford placement test grammar test part 1

- •Grammar test Part 2

- •Now tick the correct question tag in the following 10 items:

Part VI

The Museum World’s Kingmaker Crowns Again

By TOM MULLANEY

Published: April 25, 2004

What do museums do when they lose an old master? If it's a painting they call the police. If it's an esteemed leader, they call Malcolm MacKay. That's what the Art Institute of Chicago did last September when James N. Wood, 62, announced he would step down after 24 years as director.

No one wanted to repeat the fiasco of the last Art Institute search in 1977-79: the process took more than two years, and the chosen director left after only two weeks. In particular, John H. Bryan, chairman of the museum's board, was determined not to see that happen. So, knowing of Mr. Wood's plans, he reached out to Mr. MacKay, the country's leading museum-search consultant, months before the director's job was officially vacated.

Minutes after board members approved Mr. Wood's resignation, Mr. Bryan convened the 12-member search committee and introduced them to their new headhunter. Mr. MacKay (pronounced mah-KYE) is a managing director of Russell Reynolds Associates, an international executive-headhunter firm employing 40 recruiters in the New York office, where he has worked since 1989. His office, in the Met Life Building, is decorated like a living room with early-American furniture. In addition to museum officials of all varieties, he ferrets out top-job candidates for universities, foundations, think tanks and social-service agencies. Payment for this kind of work, agreed on in advance, is typically one-third of the total annual compensation expected to be offered to the chosen candidate.

For the last 15 years, Mr. MacKay has played a pivotal, yet publicly invisible, role in shaping many American museums. He placed Earl A. (Rusty) Powell 3rd at the helm of the National Gallery of Art and Jay Gates at the Phillips Collection, both in Washington; Brent Benjamin at the St. Louis Museum of Art; and Lisa Phillips at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. He has also found directors for more than 20 smaller museums, including El Museo del Barrio in New York, the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Me., and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland.

Last year, however, was particularly busy. He conducted five major searches: for the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, the Menil Collection in Houston, the Nasher Museum at Duke University, in Durham, N.C., the Frick Collection in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Mr. MacKay is a tall, energetic, rather patrician 63-year old Brooklyn native who stays trim with a regimen of tennis, swimming and squash. Deft social skills underlie his role as part diplomat and part interrogator, although he describes himself as mostly an ''expediter of information'' and maintains hundreds of dossiers on the museum world's best and brightest. As a result, his calls are both sought and feared -- his recommendations to trustees have the power to turn curators into directors, and move people from small collections to big museums. And Mr. MacKay says he's always on the lookout for new prospects. ''The winning candidates for the Menil and Frick searches, in fact, were recommendations that came from cold calls with curators and directors,'' he said.

Paradoxically, the delicate job of finding museum leaders falls to a man with no art credentials. Mr. MacKay majored in history at Princeton, after which he got a law degree at Harvard. He worked on Nelson Rockefeller's 1968 presidential campaign and then became deputy superintendent for insurance when Rockefeller was governor of New York, followed by a stint as an administrator at Long Island University. His closest association with the art world was his term on the board of the Metropolitan Museum, from 1988 to 1992, as trustee representative for Brooklyn.

Before 1980, the museum world was small and clubby; retiring directors often exerted great influence in picking their successors. This world is now a galaxy: nearly half of the museums among the 3,000 art members of the American Association of Museums were founded after 1970. Directors today rarely retain the power to name successors, and busy board members have no time to keep pace with the field's explosive growth. Also, according to Louis Grachos, the new director at the Albright-Knox Gallery, increased financial pressures have produced a more volatile museum environment. Directors now turn over every five to seven years. Unable to risk a bad selection, museums turn to consultants to bring this blur of new faces into focus.

The New Museum, for example, went through the search for a new director in 1998. Over the course of a year, it rejected three candidates before doubling back to Ms. Phillips, then at the Whitney Museum, who failed to wow the search committee the first time around. ''If we didn't have that in-between guy,'' Saul Dennison, chairman of the museum, said of Mr. MacKay, ''we'd still be at it.''

Museum search is a lucrative niche market. Three firms carve up most of the major assignments. At present, Mr. MacKay holds top honors. Two distant rivals are Sally Sterling, 42, at Spencer Stuart in Washington and Victoria Rees, 36, at Heidrick & Struggles International in New York.

Only one person ever seriously challenged Mr. MacKay's primacy. From 1994 to 2002, Nancy Nichols at Heidrick & Struggles landed many plum assignments. She first made her mark in 1994 by finding Glenn D. Lowry, then at the Art Gallery of Ontario, for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, followed by Samuel Sachs 2nd, whom she placed at the Frick Collection in 1997, and Maxwell L. Anderson for the Whitney in 1998. Her ascendancy was clinched in 1998 when the Cleveland Museum of Art asked her to find a successor for Robert Bergman, whom Mr. MacKay had placed there five years earlier.

Museum professionals credited Ms. Nichols's Harvard art credentials, wide network of contacts and ability to find a board's ''sweet spot'' for her strong credibility with trustees. In 2002, Ms. Nichols plucked James Cuno from his perch at Harvard for the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. But that was her last big coup. Later that year she died, at 57, of Lou Gehrig's disease.

Last September, at the first meeting of the Art Institute of Chicago's search committee, Mr. MacKay opened a discussion of qualities the next director should have. He convinced Mr. Bryan not to rush into naming candidates. ''The meat of the search is to discover the real needs of the board, what challenges the next director will face,'' he recalls saying. ''Fifteen years ago, I thought interviewing was the most important part. I'm now convinced it's those first discussions which play a crucial role in how the search proceeds.''

Marshall Field V, a member of the committee and a museum trustee since 1965, remembers Mr. MacKay's passing around a three-page memo raising a number of issues the search committee faced and asking after each idea, ''Is this what you really want?'' Discussion was especially spirited over whether the new director absolutely had to have art credentials or whether strong managerial skills were just as important. (Mr. MacKay notes that all natural history museums in North America are headed by nonscientists. The Field Museum in Chicago is a popular museum model at the moment; its director, John McCarter, came from the consulting arena and speaks of ''earned income streams'' as easily as of archaeological digs.)

After some revision, the group arrived at a final spec sheet. It was firm: ''The successful candidate must have significant credentials in art history and experience running complex institutions, particularly museums.''

Armed with this directive, Mr. MacKay sent letters to 100 art professionals soliciting views and nominations. At a meeting on Oct. 13 last year, the committee discussed the pros and cons of 36 sitting directors and 31 other nominees.

The committee did not want a drawn-out search with endless auditions and decided, Mr. Field said, to ''shoot the moon'' and concentrate on a short list of top-rank candidates. ''I have found that the better the institution, the easier the search,'' Mr. MacKay says. ''People line up and nominate themselves for Cleveland, the National Gallery or Chicago.''

Over the next seven weeks, he held face-to-face interviews, usually in New York, with 32 contenders from across the United States, but also from Canada, England, Europe and Australia. Most of them immediately expressed interest in being considered, but several, including Glenn Lowry, declined to be nominated.

One name began appearing in calls and letters more than any other -- James Cuno, the man Nancy Nichols, Mr. MacKay's late rival, had placed at the Courtauld. Mr. Cuno, 52, had been the director of the Harvard University Art Museums for 11 years and served as president of the Association of American Museum Directors in 2001-2. He had solid scholarly credentials and a strong but affable personality that helped him navigate the shoals of Harvard art-faculty politics. More important, he had concluded a capital campaign that surpassed its goal by 50 percent.

The one drawback was that he had been director at Courtauld for only nine months. When Mr. MacKay contacted him about the Chicago job, Mr. Cuno said the timing was ''lousy,'' but he knew that such an opportunity, at what he described as the ''leading municipal art museum in America,'' would not come around again soon. When Mr. Cuno met Mr. MacKay in New York in November he had decided to let his name be submitted to the board.

By Dec. 8, the pool was down to eight contenders: six men and two women, all top-rank directors. According to Mr. Bryan, when Mr. Cuno's name was mentioned to the search committee, John Nichols, an Art Institute board member and a former Harvard trustee, leaned over and whispered to him, ''This guy's a good one.''

That evening, Mr. Bryan flew to Europe on personal business but arranged to meet Mr. Cuno in London. Mr. Bryan's one concern was that Mr. Cuno might be too academic. Instead, he found someone with an engaging style and winning personality. Over several hours, Mr. Bryan grew more excited as he became convinced that Mr. Cuno could handle all the museum’s major constituencies: staff, trustees, collectors, donors and the public.

His fears put to rest, Mr. Bryan said, ''I then went into major selling mode.'' He invited Mr. Cuno to Chicago on Jan. 8, where he met the search committee and made a strong impression. Mr. Nichols and a Harvard Museum adviser, Lewis Manilow, spoke on his behalf, as did both staff committee members.

The committee voted unanimously to offer Mr. Cuno the position, though three other finalists remained to be seen. ''He was so superior that there was no reason to drag the whole process out,'' Mr. Bryan said. On Jan. 21, the full board voted on the nomination and the museum announced that in September Mr. Cuno would become the 13th director, at a salary reported to be $350,000 a year, in the Art Institute's 125-year history. Museum officials were pleased and sure of their choice. Mr. Wood, the retiring director, who had played no role in the search, proclaimed his satisfaction. ''I'm delighted,'' he said. ''James brings a sense of values, mission and scholarship that is consistent with this museum. He also brings us the perspective and voice of the next generation.''

The next day, newspapers nationwide reported the appointment. The spotlight was on Mr. Cuno. Mr. MacKay was nowhere to be seen. He was already back in his New York office, busy with his search for the Nasher Museum.

Tom Mullaney is a Chicago-based arts reporter.

DISCUSSION

-

What are the roles of each of these people in running a museum: a trustee, the director, a curator?

-

Give some examples of the credentials you would expect a museum director to have

-

What are the most important qualities you would expect a museum director to have?

-

What qualities would you expect in a successful headhunter?

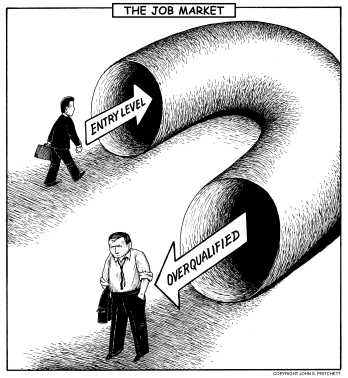

Explain the cartoon

LANGUAGE STUDY